INTRODUCTION

Mastectomy is a procedure that consists of total or partial removal of breast

tissue, varying according to the extent of resection of additional tissues

(glandular tissue, overlying skin, pectoral muscles, and regional lymph nodes).

Its main indications are for treating breast cancer and for prophylaxis in

patients at high risk of developing breast cancer (such as patients with

mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes)1. This surgery constitutes a possible source of

psychological stress that hinders the psychosocial functioning of the patient

who undergoes it, insofar as he will have to deal with tension and body

dysmorphism, in addition to several other related issues2.

Therefore, in recent years, the search for plastic surgeries for post-mastectomy

breast reconstruction has been increasing, mainly due to the benefits generated

by that procedure, such as the tendency for patients to value quality of life

more and to feel more attractive3.

However, performing anesthetic-surgical procedures in patients considered at high

perioperative risk can be a challenge, and due to the concern of

anesthesiologists and surgeons regarding the safety of the procedure, the

current trend is the implementation of protocols that revolutionize

perioperative care, improving the in-hospital management of these patients and

improving outcomes4.

Among the protocols that aim to improve the recovery of patients after surgery,

the systematic review of meta-analyses endorsed by the Enhanced Recovery After

Surgery Society (ERAS) stands out. This protocol consists of a consensus of

recommendations based on scientific evidence, which aim to promote optimal

perioperative care and generate an improved recovery, even after breast

reconstruction plastic surgery5.

Through this set of recommendations, it is possible to ensure a safer and more

efficient approach to pre-, intra-, and postoperative care. The implementation

of the protocol can bring significant benefits, such as patient engagement,

mitigation of the physiological stress associated with the surgery, reduction

of

avoidable postoperative complications (reduction of morbidity and mortality,

faster recovery, reduction of hospital stay), resulting in a reduction in

hospital costs and decrease in hospital readmission rates within 30

days6.

OBJECTIVE

The present study sought to carry out an analysis of the recommendations of the

ERAS protocol in breast reconstruction plastic surgery used in two hospitals

in

the south of the country, generating strategies for the implementation of a

protocol that aligns practice with scientific evidence, promotes institutional

leadership and encourages work in a team, engaging all parties involved in

patient care, in addition to the other previously mentioned benefits7.

METHOD

Cross-sectional study using a database of physical and electronic medical

records. The University of Southern Santa Catarina’s Research Ethics Committee

approved the study under opinion 5,570,697, CAAE 59026222.8.0000.5369, on August

9, 2022.

Female patients aged 18 years or older who underwent plastic surgery for

post-mastectomy breast reconstruction in two general hospitals in southern

Brazil between 2018 and 2021 were evaluated. The sample was of the census

type.

Variables related to the patient’s sociodemographic characteristics were

collected from the medical records (gender, age, presence of social habits,

comorbidities, BMI (Body Mass Index), and the type of procedure to be

performed); presence of preoperative advice and guidance, especially regarding

smoking cessation, pre-surgery weight loss and alcohol abstinence; performance

of pre-surgical computed tomography angiography; preoperative fasting time for

clear liquids and solid foods determined by the anesthesiologist; performance

of

preoperative conditioning with carbohydrates.

Also verified prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism and methods; skin

preparation and which substance used; administration of antibiotics before

surgery and time of its pre-surgical administration; medications used for

postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV); pre and intraoperative multimodal

analgesia; standard anesthetic protocol, containing the type of intraoperative

anesthesia used; prevention of intraoperative hypothermia; intraoperatively

administered fluids; prescription of postoperative analgesics; time to start

oral fluid intake and to walk after surgery; time to hospital discharge.

Additionally, we analyzed immediate complications and readmissions.

Categorical variables were presented as absolute frequencies and percentages, and

continuous variables as mean and standard deviation (SD). The follow-up rate

per

patient was calculated by simple arithmetic mean. Spearman’s correlation

coefficient was used to assess the statistical dependence between two variables.

The adopted statistical significance level was 5%

(p<0.05).

RESULTS

During the study period, 99 breast reconstruction procedures were performed, 100%

of which were female patients. The median age of patients was 56 years

(SD=15.75), ranging from 19 to 81. Mean BMI was 26.97 kg/m2

(SD=4.22). Data related to the study and procedure participants are presented

in

Table 1.

Table 1 - Characteristics of patients undergoing breast reconstruction surgery

(n=99).

| Variable |

n |

% |

| Age |

|

|

| 19-30 years |

15 |

15.2 |

| 31-50 years |

34 |

34.3 |

| > 50

years

|

50 |

50.5 |

| Social habits / Comorbidities

(pre-admission) |

| Smoking |

8 |

8.1 |

| Obesity |

26 |

26.3 |

| Alcoholism |

4 |

4.0 |

| BMI |

| < 18.5 |

1 |

1.0 |

| 18.6 - 24.9 |

34 |

34.4 |

| 25.0 - 29.9 |

43 |

43.4 |

| 30.0 - 34.9 |

16 |

16.1 |

| 35.5 - 39.9 |

6 |

5.1 |

| > 40 |

- |

0.0 |

| Procedure to be

performed |

| Prosthesis And/Or Expander |

35 |

35.4 |

| Post-Quadrantectomy Partial Reconstruction |

45 |

45.5 |

| Muscular or myocutaneous flap |

13 |

13.1 |

| Regional Skin Flaps |

6 |

6.1 |

Table 1 - Characteristics of patients undergoing breast reconstruction surgery

(n=99).

Of the patients who participated in the study, 100% underwent pre-anesthetic

evaluation, receiving information, education, and detailed preoperative

counseling, as seen in Figure 1. The data

presented are followed by their Level of Evidence (LE).

Figure 1 - Adherence to the indications strongly recommended in the ERAS

protocol for breast reconstruction plastic surgery. ERAS: Enhanced

Recovery After Surgery.

Figure 1 - Adherence to the indications strongly recommended in the ERAS

protocol for breast reconstruction plastic surgery. ERAS: Enhanced

Recovery After Surgery.

The optimization of pre-admission - which consists of carrying out, before

surgery, one month of abstinence from tobacco for smokers (LE = moderate); one

month of abstinence from alcohol for alcoholics (LE = moderate); and weight

reduction in obese patients to reach a BMI ≤ 30kg/m2 (LE = high) -

was performed by 52.5% of patients. Flap planning, with preoperative mapping

of

perforating vessels with angiotomography (LE = moderate), was performed by only

1.0% of patients (n=1).

Minimized perioperative fasting was indicated for 84.8% of patients, who were

allowed to drink clear liquids up to two hours before surgery (LE = moderate).

None of the patients were given preoperative drinks based on maltodextrin in

the

two hours before the surgery (LE = low).

During the preand intraoperative period, multimodal analgesia to alleviate pain

was performed in 100% of patients (LE = moderate). The standard anesthetic

protocol with total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) was not performed on any

patient; in contrast, all patients received combined general anesthesia.

Preoperative and intraoperative measures to avoid hypothermia, as well as

perioperative intravenous fluid management, in an attempt to avoid excessive

or

insufficient fluid resuscitation (LE = moderate), were indicated in only 2.0%

of

the medical records (n=2).

Postoperatively, 22.2% of patients were encouraged to take liquids and food

orally as soon as possible, preferably within 24 hours after surgery (LE =

moderate) (n=22). Frequent monitoring of the flap in the first 72 hours after

the operation was indicated by the nursing team in only 2% of the medical

records (n=2).

No information was found in the medical records about early mobilization in the

first 24 hours after surgery (LE = moderate) and post-discharge home support

and

physiotherapy (LE = moderate).

The average rate of compliance with the ERAS protocol per participant was 50.7%.

Regarding the perioperative procedures performed, as shown in Table 2, surgical management was performed

in 99% of patients, all receiving conventional sutures for incisional closure

(LE = high) (n=98).

Table 2 - Procedures performed in patients undergoing breast reconstruction

surgery (n=99).

|

n |

% |

| Wound

management |

|

|

| Conventional

suture

|

98 |

99.9 |

| NPWT |

- |

0.0 |

| Prophylaxis of venous

thromboembolism in high-risk patients |

| Mechanical prophylaxis |

56 |

56.6 |

| Pharmacological prophylaxis with LMWH |

24 |

24.2 |

| Pharmacological prophylaxis with UFH |

23 |

23.1 |

| Skin

preparation |

|

|

|

Chlorhexidine

|

90 |

90.9 |

| Antibiotic given

within 1 hour before incision

|

97 |

98.0 |

| Alcoholism |

4 |

4.0 |

| Medications for VONV |

|

|

| Dexamethasone |

65 |

65.7 |

| Ondansetron |

67 |

67.7 |

| Metoclopramide |

36 |

36.7 |

| Other |

11 |

11.1 |

| Pre and intraoperative analgesia and

sedation |

| Opioid |

99 |

100.0 |

| Muscle

relaxant

|

99 |

100.0 |

|

Benzodiazepine

|

99 |

100.0 |

| Standard anesthetic protocol |

|

|

| TIVA |

- |

0.0 |

| Balanced general anesthesia |

99 |

100.0 |

| Postoperative analgesia |

|

|

| Dipyrone |

44 |

44.4 |

|

Acetaminophen

|

60 |

60.6 |

| INES |

68 |

68.7 |

|

Corticosteroid

|

36 |

36.4 |

| Weak

opioida |

21 |

21.2 |

| Strong

opioidb |

29 |

29.3 |

| Other |

8 |

8.1 |

Table 2 - Procedures performed in patients undergoing breast reconstruction

surgery (n=99).

The risk of venous thromboembolism was assessed in 80.8% of patients (n=80), with

56.6% receiving mechanical methods for prophylaxis (n=56); 24.2% received low

molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (n=24); and 23.1% received unfractionated

heparin (UFH) (n=23) until ambulation or discharge (LE = moderate).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis was performed in 99.0% of patients (LE = moderate)

(n=98). Of these, 90.9% had their skin prepped with chlorhexidine (n=90), and

98.0% received intravenous antibiotics covering common skin organisms within

one

hour of incision (n=97).

Preand intraoperative medications to attenuate postoperative nausea and vomiting

were administered to 85.9% of patients (LE = moderate) (n=85). Of the drugs

used: dexamethasone 65.7% (n=65); ondansetron 67.7% (n=67); metoclopramide 36.7%

(n=36); and another 11.1% (n=11). For pain control, 100% of patients received

multimodal drug regimens (LE = high).

Of these drugs: dipyrone 44.4% (n=44); acetaminophen 60.6% (n=60); non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 68.7% (n=68); corticosteroid 36.4 (n=36); weak

opioid (codeine, tramadol, dextropropoxyphene, hydrocodone) 21.2% (n=21); strong

opioid (fentanyl, methadone, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone) 29.3% (n=29);

another 8.1% (n=8).

According to the results shown in Table 3,

which represents the postoperative outcomes, all patients were discharged.

However, there was a prevalence of 29.3% of cases of complications. The three

main causes of complications were pain (15.2%), nausea and vomiting (11.1%),

and

constipation (3.0%). In addition, 20.2% of patients needed to be readmitted.

Table 3 - Outcomes of patients undergoing breast reconstruction

surgery.

|

n |

% |

| Discharge |

99 |

100.0 |

| Complication |

29 |

29.3 |

| Pain |

15 |

15.2 |

| Nausea and vomiting |

11 |

11.1 |

| Cold |

3 |

3.0 |

| Readmission |

20 |

20.2 |

Table 3 - Outcomes of patients undergoing breast reconstruction

surgery.

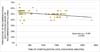

When analyzing the mean length of stay (11 hours and 52 minutes) and its

relationship with the number of indications with a strong degree of

recommendation achieved, a moderate negative correlation was observed between

the variables. Figure 2 shows this

statistical dependence as a decreasing monotonic trend; that is, as the number

of indications with a strong degree of recommendation achieved increases, the

length of stay decreases until the patient is discharged (Spearman ρ = -0.397)

(p<0.001).

Figure 2 - Relationship between the number of ERAS protocol recommendations

followed and length of stay until discharge.ERAS: Enhanced Recovery

After Surgery.

Figure 2 - Relationship between the number of ERAS protocol recommendations

followed and length of stay until discharge.ERAS: Enhanced Recovery

After Surgery.

DISCUSSION

Each element of the ERAS protocol is designed to decrease the physiological

stress of the surgical intervention, and there is evidence in the literature

that each recommendation is associated with several clinical benefits, including

a shorter hospital stay. However, low adherence or implementing only a few

recommendations is insufficient to achieve all the expected benefits. Compliance

with most items can be crucial to achieving a desired clinical outcome,

producing greater clinical benefits than their parts8.

The present study’s results align with a pilot study of ERAS in the National

Surgical Quality Improvement Program (PNMQC) of the American College of Surgeons

(ACS), which included 16 hospitals that implemented the protocol in more than

1,500 patients. The study found that the mean length of stay increases as

adherence to the ERAS protocol decreases (p<0.001),

reinforcing the importance of complete adherence to recommendations to achieve

the expected clinical benefits8,9.

This information is important, as most patients with breast cancer have a

time-dependent disease, which means that the recovery time and the effectiveness

of the treatment directly affect the post-mastectomy result; that is, the faster

and more effective the recovery, the greater the chance of cure or control of

the disease. Furthermore, mastectomy is often followed by additional therapies

such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which can also have significant adverse

effects. Therefore, recovery optimization can help to minimize the total

treatment time and reduce the risk of related complications10.

It is known that not all ERAS protocol steps apply to each patient. However,

collecting data from medical records about their adherence at an individual

level allows providers to identify which protocol components are problematic

and

target their interventions to improve compliance9.

In this order of ideas, we have, for example, that, during the preoperative

evaluation, smoking cessation should be oriented to all patients; however, only

half reached this recommendation. Studies point out that the persistence of

smoking in the perioperative period results in higher rates of postoperative

complications, mainly infection of the incisional wound11. Spontaneous smoking cessation

is related to several biopsychosocial factors. Therefore, to achieve this

recommendation, it is necessary to implement a multidisciplinary

follow-up12.

Preoperative optimization using carbohydrates such as maltodextrin prevents the

catabolic state induced by the surgical stress response, reduces postoperative

nitrogen and protein losses, helps maintain lean body mass and muscle strength,

and decreases insulin resistance. Added to this, it reduces preoperative thirst,

hunger, and anxiety13. This

recommendation, however, still qualifies as a low level of evidence, and its

benefits vary according to the type of surgery and the patient evaluated, which

would explain the low adherence in the target sites of the present

study14.

In large centers, physiotherapy is still performed in the post-anesthetic

recovery room, even with the patient on mechanical ventilation15. This study, however,

demonstrated that there was no early mobilization in the patients studied. As

a

result of the various barriers that are imposed on this recommendation, its

implementation requires the efforts and engagement of a multidisciplinary

team.

Furthermore, it was noted that the analgesia was administered intravenously,

predominantly, which goes against the current literature, which recommends

multimodal perioperative analgesia, using combinations of analgesic medications

that act in different sites and routes, in an additive or synergistic, to obtain

pain relief with minimal or non-existent consumption of opioids16.

A standard anesthetic protocol with TIVA is intended to minimize anesthetic side

effects and facilitate rapid awakening and recovery after surgery. However,

compared to balanced techniques, the superiority in choosing this anesthetic

technique was seen only in some specific situations. Among the main obstacles

to

its adherence are the high cost, the low availability of equipment, and the need

to train professionals who are possibly already used to other techniques,

according to the respective anesthesiology service17.

It is known that hypothermia occurs in 70% of patients undergoing operations

lasting two or more hours, increasing intraoperative blood loss. It is usually

preventable through active warming using a blanket and thermal mattress. The

use

of dynamic monitors and fluid-responsiveness measurements also guide fluid

utilization. However, in small to moderate surgeries with a non-prolonged

duration and low risk of bleeding, the cost and availability of these

instruments often constitute an obstacle to their use18.

Adherence to the ERAS protocol can be deficient due to several reasons. One of

the main barriers is the lack of knowledge of the protocol by health

professionals who are part of the surgical team. The difficulty of raising

awareness about the need to change habitual behaviors can be hard in this

process. Another barrier may be the lack of resources or adequate infrastructure

to implement the protocol, especially in smaller hospitals or with fewer

available resources19.

To achieve better clinical outcomes, these barriers must be addressed and

overcome. Education of surgical teams and training for the ERAS protocol can

be

essential to improve adherence and understanding of the corresponding benefits.

It is also important to provide adequate support and resources for implementing

the protocol in hospitals, including the availability of a multidisciplinary

team to support its implementation. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of

results are essential to ensure that the protocol is being properly implemented

and to identify opportunities for improvement20.

Furthermore, the ERAS protocol offers a unique opportunity to leverage existing

resources by instituting a standardized approach to anesthesia and

surgery-related challenges. This allows growing hospitals to increase their bed

capacity and, consequently, the surgical volume, generating a potential increase

in gross revenue due to the savings in hospitalization days21.

CONCLUSION

The average rate of compliance with the ERAS protocol per participant was 50.73%.

The mean length of stay was 11 hours and 52 minutes. The number of indications

with a strong degree of recommendation achieved showed the ability to reduce

the

time, in minutes, from hospitalization to discharge (Spearman’s ρ = -0.397)

(p<0.001). This demonstrates the need for greater

protocol adherence to reduce the length of hospital stay.

Study limitations

It is important to consider the inherent limitations of ecological studies

that use medical records as a database. One of the main concerns is the

quality of the data, which can vary widely between health professionals

responsible for completing the records, affecting the accuracy of the

results obtained and the validity of the conclusions reached. Another

important aspect to be considered is data availability. Medical records do

not always contain all the information relevant to a study, which may limit

researchers’ ability to explore certain questions. In addition, charts are

generally collected from a specific sample of patients in a particular

geographic location, which may restrict the generalizability of results to

other populations or locations.

1. Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina, Tubarão,

SC, Brazil

2. Nossa Senhora da Conceição, Tubarão, SC,

Brazil

Corresponding author: André Gabriel Gruber Avenida

José Acácio Moreira, 787, Tubarão, SC, Brazil., Zip Code: 88704-900, E-mail:

andre.gruber@hotmail.com