Ideas and Innovation - Year 2023 - Volume 38 -

Description of the S-Apple mixed rotation and transposition flap: preliminary note

Descrição do retalho misto de rotação e transposição S-Apple: nota prévia

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The flaps, whose function is to reduce or redirect tension during a closure, are classified based on their primary movement: transposition, advancement, and rotation, each with its characteristics, indications, and peculiarities. Combining the qualities of the transposition flaps with those of rotation, which make up the S-Apple flap, makes it more versatile and with better aesthetic results than the bilobed flap, which denotes the archetype for the appearance of the S-Apple.

Method: Having the rotation and transposition flaps as an archetype, four flaps are made in the S-Apple flap, which are rotated and transposed to close the defect. This is excised in a circular format for the oncological safety of margins. The "S" of the flap is traced at a 30º angle in relation to the defect. The arm dimension must be the same diameter as the defect, with the flaps transposed as in a z-plasty, and the flap rotated to cover the defect, resulting from the exeresis of the lesion.

Results: No necrosis, infection, dehiscence, recurrences, trapdoor scars, or rotation point elevation were observed. The scars were classified as satisfactory and extremely satisfactory.

Conclusion: The S-Apple flap proved versatile and easy to mark with excellent aesthetic and functional results.

Keywords: Surgical flaps; Free tissue flaps; Rotation; Therapeutic uses; Skin

RESUMO

Introdução: Os retalhos, com função de reduzir ou redirecionar a tensão durante um fechamento, são classificados com base em seu movimento primário: transposição, avanço e rotação, cada um com suas características, indicações e peculiaridades. O arregimentar das qualidades dos retalhos de transposição com os de rotação, que compõem o retalho S-Apple, tornam-no mais versátil e com melhores resultados estéticos em relação ao retalho bilobado, que denota o arquétipo para o surgimento do S-Apple.

Método: Tendo como arquétipo os retalhos de rotação e transposição, no retalho S-Apple são confeccionados quatro retalhos, que são rotacionados e transpostos para fechamento do defeito. Este é excisado em formato circular para segurança oncológica de margens. O "S" do retalho é traçado em um ângulo de 30° em relação ao defeito. A dimensão do braço deve ser do mesmo diâmetro do defeito, sendo os retalhos transpostos como em uma zetaplastia e o retalho rotacionado para cobrir o defeito, resultante da exérese da lesão.

Resultados: Não foram observadas necroses, infecção, deiscências, recidivas, cicatrizes em alçapão e elevação em ponto de rotação. As cicatrizes foram classificadas como satisfatórias e extremamente satisfatórias.

Conclusão: O retalho S-Apple se mostrou um retalho versátil de fácil marcação com excelentes resultados estéticos e funcionais.

Palavras-chave: Retalhos cirúrgicos; Retalhos de tecido biológico; Rotação; Usos terapêuticos; Pele

INTRODUCTION

Among many indications for flaps, there is their use when simple closing techniques do not produce an acceptable functional or aesthetic result. They also have the function of reducing and/or redirecting tension, making them an indispensable tool in closing complex wounds or in noble areas. They can be classified based on their primary movement: transposition, advancement, and rotation1.

Transposition flaps incorporate the non- contiguous skin in a primary defect, lifting the flap over the normal skin in a defect, and have head and neck skin defects as their main indication2. Advancement flaps recruit adjacent tissue to close a defect in a linear direction, while rotation flaps rotate adjacent tissue around an axis to close a primary defect, rotating the skin into the defect1.

Numerous possible modifications can be learned from the literature in the described flaps, as opinions vary between surgeries concerning the ideal development of a rotating flap3.

Rotation flaps are indicated when other simpler types of closure do not provide a functional and aesthetic result, being suitable for triangular defects adjacent to the transferable skin, such as lesions in the zygomatic region, buccinator, chin, and scalp; they can redirect stress around a free edge and avoid distortion. Such flaps are created with an arched or curvilinear incision combining advancement and rotation1,4.

Due to the primary movement of the flap, a cutaneous deformity on the rotation pedicle, called “dog ear,” can form along the arch on the opposite side of the primary defect, bringing aesthetic damage to the patient and the need for a new intervention to correct this elevation in the pedicle. To minimize the defect and closing tension, the triangulation technique must be adjusted so that the redundant tissue area is excised and the geometric pivot point ideally coincides with the apex of the triangulated defect1,3,5.

The rotation flap archetype is framed by the bilobed flap, which, as it only rotates, has all the disadvantages described above, such as a “dog ear” on a rotation pedicle, fixed location of the pedicle in nasal reconstructions, with a pedicle that is obligatorily lateral in reconstructions. of dorsal lesions and dorsal/central pedicles in reconstructions of lateral lesions, which reduces its versatility in relation to the S-Apple proposed here.

The flap proposed here, as a modification of the bilobed flap, manages to incorporate the advantages of a rotation flap with the advantages of a transposition flap, providing a versatile technique that can be used in different situations to produce excellent functional and aesthetic results, without the restriction of the positioning of rotation pedicle or sites of use. This archetype justifies the proposal of the present work to develop the S-Apple flap.

OBJECTIVE

To describe a versatile mixed rotation and transposition flap for closing defects without new interventions for aesthetic and/or functional refinements.

METHOD

The flap was developed based on the archetype of the bilobed rotation flap, a versatile flap, but which has the disadvantages of raising the point of rotation – “dog’s ear” and a limitation in the sizes and locations of the lesions that can be repaired, as well as such as, in nasal reconstructions, the obligation to have a fixed rotation pedicle in the dorsum/central region for lateral defects and a fixed lateral pedicle for dorsal/central defects.

All patients were explained about the procedures, risks, and possible complications, and an informed consent form for participation in the study was used.

Such procedures followed the norms of the Institution’s Research Ethics Committee and CNS Resolution 196/96.

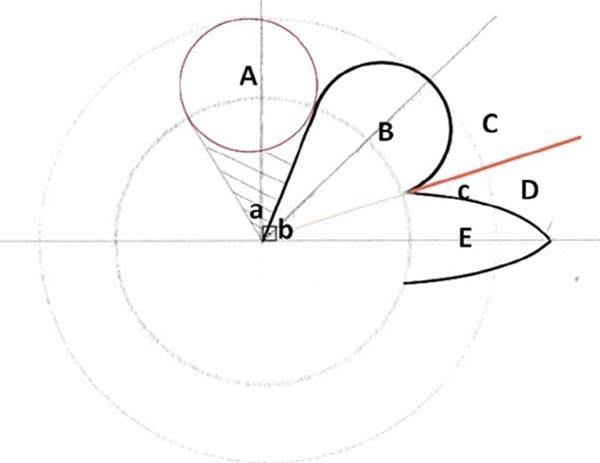

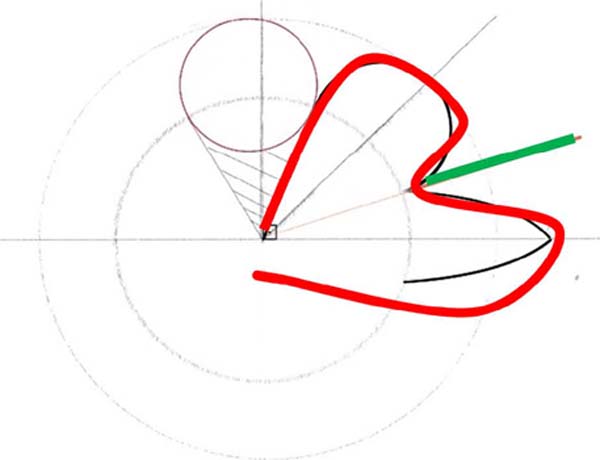

The S-Apple Flap flap was designed according to the scheme in Figure 1, in which the traced angles are observed, with the defect always removed in a circular format and the flap arms drawn at approximately 60° (angles a and b). The line in red demonstrates the creation of the “S” of the flap; it is made up as a zeta line, being drawn at a 30° angle (angle c) of the X axis in relation to the defect. The dimension of the arm of the flap adjacent to the defect must be of the same diameter (diameter of A = diameter of B), with flaps D and E being transposed as in a zetaplasty and flap C rotated to fill the space left by flap B, which will rotate to cover the A defect resulting from excision of the lesion.

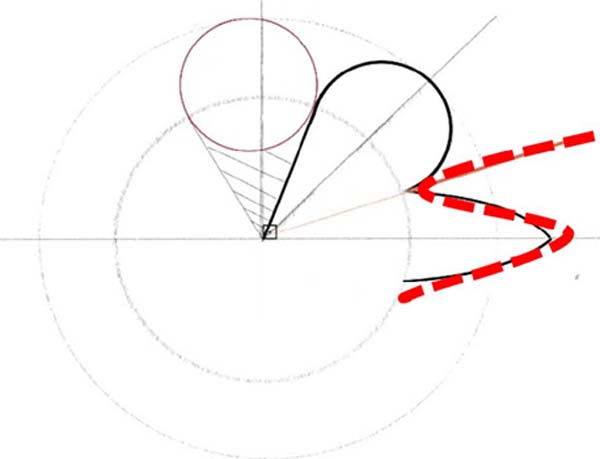

The justification for naming it the S-Apple Flap is the format resulting from the marking of the flap, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, which depicts the shape of an apple at the end of the marking, also exemplified in the cases described.

All patients were followed up for 3, 6, and 12 months, with standardized photographic records taken according to the protocol, a validated questionnaire on body image satisfaction, and a scar quality scale. Data were tabulated for further statistical analysis.

RESULTS

As preliminary results, no necrosis, infection, or dehiscence occurred. All patients had a satisfaction index of Good or Great. All presented scar quality classification as satisfactory and extremely satisfactory; there was no recurrence in the sample. Such data will be the motto of the complete work, with the demonstration of statistical significance after analyzing the instrument data.

There were no trapdoor scars or elevation at the flaps’ rotation point. None of the cases required re-approach to correct an unsightly scar or to thin the pedicle.

Below are pre- and postoperative examples to illustrate the aforementioned (Figures 4,5,6,7). The versatility of locating the flap in the nasal region and the possibility of using it in larger lesions can be seen in Figure 8. Figures 9,10, 11 show an example of using the flap in breast reconstruction.

DISCUSSION

Among the different rotational flap techniques, double rotation flaps for closing large defects in a single time are relevant in the literature and generally used on the scalp and around the free margins. The O to Z flap is a double rotation flap used in the central region of the scalp or large lesions on the trunk, which effectively converts the circular or “O” shaped defect into a “Z” shaped suture line1,2. A variation of this flap is the pinwheel, which uses three or more rotation flaps, useful for scalp and trunk defects.

The original Peng flap6 corresponds to an advancement flap, which can be modified to add a rotational component, essentially a double rotation flap in which the point of articulation is located along the midline at the nasal root. This flap can be indicated as an alternative for defects that require a paramedian flap, but it can lead to distortion of the symmetry of the nose and elevation of the nasal tip1,6.

Concerning exclusive rotation flaps, Rieger7 first proposed the dorsal nasal rotation flap in 1967, used for larger defects of less than 2 to 3cm in size in the distal nose in a single stage. Marchac & Toth8 described an axial pattern flap, but some patients do not have the necessary tissue laxity to perform the flap, which may cause loss of nasal symmetry, the elevation of the nasal tip and ala, and distortion of the ala1,5,8.

Special care must be taken to avoid ectropion when addressing lower eyelid and infraorbital cheek defects. Tenzel & Stewart9 and Mustardé10 described rotation techniques that disperse tension in the horizontal plane, avoiding excessive tension in the lower eyelid. However, the Mustardé flap10 can induce ectropion due to the weight of the flap, requiring sutures. The Tenzel flap9 is a myocutaneous flap with less rotation, not requiring sutures1,5,9,10.

The spiral flap has several proposed uses, including defects in the lower eyelid, ventral fingertip, nasal ala, and lateral and inferior nasal tip, with the potential to preserve the alar sulcus. The cervicofacial flap is used for very large cheek defects, being created similarly to a Mustardé and Tenzel flap, with the incision made towards the neck, also requiring sutures due to its size1,5,9,10.

Transposition flaps, designed in a random pattern, must be elevated over an area of normal skin to reach the eventual destination in the primary defect. They are generally used in the head and neck because of their ability to redirect tension and recruit a reservoir of tissue not immediately adjacent to the defect, redirecting tension away from the primary defect, and may avoid distortion of the free margins. The classic flap corresponds to a single lobe, which recruits tissue from an adjacent reservoir. However, single-lobe transposition modifications include the Rhombic, Banner, and Note2 flaps. Multilobed modifications of the transposition flap, such as bilobed, trilobed, and tetralobed flaps, allow the recruitment of tissue reservoirs increasingly distant from the primary defect2.

The bilobed flap, described for the first time in 1918 by Esser11 for use in the reconstruction of the nasal tip, consists of a local transposition flap, presenting in its original variant a total arc of rotation between 90 and 110°, this proposal by Zitelli12, which is currently the most used. Such an indication fell into disuse, as the large arch created large flaps that required significant weakening, giving space to use for the lateral portion of the nose.

The flap consists of a double transposition in which the first lobe fills the primary defect, and a second lobe fills the secondary defect, distributing tension over a wider area than the conventional rotational flap. Compared to the S-Apple, the incisions create four flaps, two rotated, and two transposed. Differences in the rotation angles and shapes of the arms of the flaps allow the closure of larger lesions without aesthetic deformities and tissue distortions such as raised pedicles and trapdoor scars.

Contraindications for the transposition of bilobed flaps include any conditions that substantially decrease soft tissue viability in the area in question, such as scarring, history of radiation or infection, and active inflammation. As complications, we can mention the trapdoor cushion deformity, which consists of a depressed area compared to the surrounding tissue, being related to contraction of the subdermal tissue and which can be minimized by decreasing the arc of rotation2,13.

In this regard, using the S-Apple Flap promoted the absence of trapdoor scars, no elevation in the rotation point, and no need for a new approach for aesthetic refinement. In addition, the absence of necrosis, infection, and dehiscence was also described, as well as patient satisfaction regarding the quality of the scar. The versatility of flap location and the possibility of performing it in larger lesions stand out as another quality of the described flap.

Advantages of using rotation flaps include simplicity, good blood supply via a large pedicle, minimal tissue redundancy, and the ability to place rotational lines in creases or natural edges to extend the flap to increase laxity easily. On the other hand, the disadvantages of the rotation flap are the need for careful design evaluation and the potential for revisions inherent to all flaps.4,5

However, excessive tension, wound contracture, swelling, scarring, flap necrosis, infection, and bleeding are common flap complications that can be avoided with careful planning and proper technique. Furthermore, rotation flaps that do not adequately disperse stress vectors can distort sensitive structures1,4,14.

The concern with force vectors circumscribes not only the flaps used for reconstruction of important structures such as the nose15,16 but also several other body regions that need symmetry, such as breast reconstruction, in which the positioning of scars and force vectors allow more natural and symmetrical reconstructions to the untreated breast and avoid anatomical distortions due to subsequent scar retractions17.

Such disadvantages were resolved by merging two types of flaps into one. With the S-Apple Flap, it was possible to unite the advantages of rotation flaps with the advantages of transposition flaps, using each one to overcome the inherent disadvantages of each flap type. Preliminarily, there were no complications in the sample performed, with excellent aesthetic and functional results and great versatility, allowing its use for closing larger defects without anatomical distortions and without the need for pedicles in fixed positions.

CONCLUSION

The S-Apple flap proved versatile and easy to mark, combining the advantages of the rotation and transposition flaps.

1. Instituto Sundfeld de Cirurgia Plástica, São Carlos, SP, Brazil

3. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São Carlos, SP, Brazil

3. Escola Paulista de Medicina, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

4. Unifai, Adamantina, MG, Brazil

Corresponding author: Daniel Sundfeld Spiga Real Rua Dr. Domingos Faro, 285, Jd. Alvorada, São Carlos, SP, Brazil. Zip code: 13.562-003 E-mail: dplasticsurgery@hotmail.com

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter