Original Article - Year 2023 - Volume 38 -

Abnormalities in preoperative examinations of plastic surgery patients

Anormalidades em exames pré-operatórios de pacientes de cirurgia plástica

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Preoperative tests (EPO) aim to detect abnormalities and give greater safety to the procedure. However, the request for these tests is still controversial, either because they do not bring about changes in conduct for the procedure or result in some harm to the patient. The objective is to assess the frequency of EPO requests and abnormalities in aesthetic plastic surgery patients, to verify what these abnormalities are, what preoperative management should be done based on the finding, and to associate the data obtained with the patient's profile and the planned surgery.

Method: Retrospective study evaluating medical records of aesthetic plastic surgery patients who underwent routine EPO in a plastic surgery hospital in 2019.

Results: 978 patients were studied, and 51% had some abnormality in EPO. 93.7% were women, with a mean age of 46.5 years. 12.3 exams were performed per patient, and abnormality was observed in 6.1% of EPO. The exams that had the most abnormalities were the lipidogram (23.8%) and the cardiac evaluation (14.1%). Hypothyroidism was the most common comorbidity (18.4% of patients); 70% of diabetics had a glycemic level above the recommended level. Only 3.4% of the patients suffered a change in preoperative management due to EPO abnormality, and in 57.9% of these cases, the surgery was postponed. Test alterations were more frequent in male patients (p<0.0001).

Conclusion: The performance of routine EPO showed a low frequency of altered exams (3.4%) and implied changes in the preoperative conduct of plastic surgery patients.

Keywords: Diagnostic tests, routine; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Preoperative care; Patient care management; Health care costs.

RESUMO

Introdução: Os exames pré-operatórios (EPO) visam detectar anormalidades e dar maior segurança ao procedimento. No entanto, a solicitação desses exames ainda é controversa, seja por não trazerem mudanças de conduta para o procedimento ou resultar em alguns malefícios para o paciente. O objetivo é avaliar a frequência de solicitações e de anormalidades dos EPO em pacientes de cirurgia plástica estética, verificar quais são estas anormalidades, qual conduta pré-operatória mediante o achado e associar os dados obtidos com o perfil do paciente e cirurgia prevista.

Método: Estudo retrospectivo avaliando prontuários de pacientes de cirurgia plástica estética que realizaram EPO de rotina em um hospital de cirurgia plástica durante o ano de 2019.

Resultados: Foram estudados 978 pacientes e 51% desses apresentaram alguma anormalidade nos EPO. 93,7% eram mulheres, com média de idade 46,5 anos. Foram realizados 12,3 exames por paciente e observada anormalidade em 6,1% dos EPO. Os exames que mais tiveram anormalidades foram o lipidograma (23,8%) e os da avaliação cardíaca (14,1%). Hipotireoidismo foi a comorbidade mais achada (18,4% dos pacientes); 70% dos diabéticos estavam com o nível glicêmico acima do recomendado. Apenas 3,4% dos pacientes sofreram alteração da conduta pré-operatória devido anormalidade dos EPO e em 57,9% desses casos houve adiamento da cirurgia. Alterações de exames foram mais frequentes em pacientes do sexo masculino (p<0,0001).

Conclusão: A realização de EPO de rotina mostrou baixa frequência de exames alterados (3,4%) e implicou em mudanças na conduta pré-operatória em pacientes de cirurgia plástica.

Palavras-chave: Testes diagnósticos de rotina; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Cuidados pré-operatórios; Administração dos cuidados ao paciente; Custos de cuidados de saúde

INTRODUCTION

The preoperative evaluation is a procedure that precedes an operative process, and its main objectives are to bring safety and reduce morbidity for the patient related to anesthesia and surgery1,2; in addition to reducing the patient’s anxiety before surgery, the number of canceled surgeries, the costs of exams and specialized consultations in the preoperative period and reducing time, costs and intercurrences in the operative and postoperative period 3,4.

Among the tests available, the most requested are complete blood count, coagulation test, electrocardiogram (ECG), chest X-ray, urea/creatinine, electrolytes, blood glucose, and liver function test2,5. These exams aim to identify, diagnose or evaluate present diseases and dysfunctions and help to elaborate an anesthetic and surgical plan that brings safety and surgical quality to the patient4,6.

The request for preoperative exams (EPO) should be done selectively5 and mainly consider the surgery to be performed, the data from the anamnesis, and the physical examination obtained in the preoperative consultation, as recommended by protocols for requesting preoperative exams7,8. However, some professionals request a battery of tests, without any clinical indication, intending to diagnose diseases not previously identified in the anamnesis and physical examination to have greater confidence in decision-making and/or to ensure judicial security1,2,4. In addition, some physicians do not feel confident or are unaware of the proposed guidelines, and the request for tests brings greater patient satisfaction, encouraging physicians to request more tests9.

However, some studies show that these EPOs have no practical use and can even harm the patient2,4,10. The battery of laboratory tests may not bring relevant results for planning and performing surgery2,4,10. Some results may reveal abnormalities of no clinical importance11 and still have low predictive value in healthy patients12. These tests can still lead to false-positive results, motivating further investigations and thus exposing the patient to new risks and stress, causing greater morbidity, postponement of surgery, and additional costs for perioperative preparation2,6,11,12. In addition, the indiscriminate request for tests results in a high and unnecessary cost for the health system4.

Some authors estimate that between 60% and 70% of EPO are requested incorrectly, without adequate clinical indication13 and that between 30% and 60% of unexpected abnormal results found in EPO are not investigated, a practice that can lead to legal risks for the doctor, contrary to the thought that requesting more tests leads to greater legal protection14.

Few studies address the frequency of EPO abnormalities in the preoperative management of the patient, mainly focusing on aesthetic plastic surgery patients. Although aesthetic plastic surgery is considered an elective surgery, it has some differences from other surgeries: it is a type of procedure that only accepts patients who are healthy and has a lower risk compared to most other elective surgeries15.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to identify the frequency of EPO abnormalities in patients referred for surgery at a plastic surgery hospital and classify which are present. Additionally, associate the data obtained with the gender and age of the patients, the type of surgery planned, and verify whether the surgery was canceled, postponed, or performed.

METHOD

The research was approved by the research ethics committee of Instituto Presbiteriano Mackenzie (CAAE: 35523420.1.0000.0103). The study has a retrospective design and was carried out with the analysis of medical records of plastic surgery patients from January 1 to December 31, 2019, at a plastic surgery hospital in Curitiba-PR.

Patients over 18 years of age and of both genders who underwent liposuction, abdominoplasty, mammoplasty, rhytidectomy, rhinoplasty, and blepharoplasty were included. The plastic surgeon first saw the patient, then referred them for a pre-anesthetic consultation with an anesthetist and an evaluation by a cardiologist. Cases of incomplete medical records were excluded.

The hospital protocol requests the following preoperative routine tests for all patients: complete blood count, coagulogram, electrocardiogram, urea/creatinine, and blood glucose. Other tests can be requested selectively, according to the patient’s profile and the findings of the preoperative consultation, intending to perform a more in-depth evaluation of the patient. In the studied hospital, the request for EPO and other necessary tests, in general, are made by anesthesiologists and/or cardiologists.

The ASA classification was used to assess the surgical risk. (American Society of Anesthesiologists16. The variables collected were: age, sex, comorbidities, data on which EPO, result, conduct in the face of an abnormal test and its outcome, planned surgery, and the surgery status.

Statistical analysis

The data collected were spreadsheets using the Excel program. Descriptive statistics were performed using the Graph Pad Prism 5.0 program. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared using the chi-square test, as appropriate. P values less than 5% were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

During the study period, 1336 plastic surgery patients were treated. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 358 cases were not classified for the study, totaling 978 eligible cases.

The mean age of the patients was 46.5 years, with a minimum age of 18 years and a maximum of 85 years. The mean age for female patients was 46.5 years, whereas, for male patients, the resulting mean age was 47.4 years. Table 1 provides the patients’ demographic data relating to the presence or absence of an abnormal test. All patients underwent at least one preoperative examination, and 499 (51%) had one abnormal examination. Most of them are female (n=916; 93.7%). Patients with ASA 2 (n=532; 54.4%) and patients with comorbidities (n=539; 55.1%) were more frequent, and the most common surgery was mammoplasty (n=441; 45%).

| Data | Standard Exam | Abnormal Exam | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexa | |||

| F | 463 (50.5%) | 453 (49.5%) | 916 (93.7%) |

| M | 16 (25.8%) | 46 (74.2%) | 62 (6.3%) |

| ASAb | |||

| 1 | 353 (79.1%) | 93 (20.9%) | 446 (45.6%) |

| 2 | 86 (16.2%) | 446 (83.8%) | 532 (54.4%) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Without | 261 (59.5%) | 178 (40.5%) | 439 (44.9%) |

| With | 218 (40.4%) | 321 (59.6%) | 539 (55.1%) |

| Surgery | |||

| Mammaplasty | 259 (58.7%) | 182 (41.3%) | 441 (45%) |

| Liposuction | 159 (55.6%) | 127 (44.4%) | 286 (29.2%) |

| Rhytidectomy | 77 (33.3%) | 154 (66.7%) | 231 (23.5%) |

| Blepharoplasty | 75 (39.1%) | 117 (60.9%) | 192 (19.5%) |

| Abdominoplasty | 92 (55.8%) | 73 (44.2%) | 165 (16.8%) |

| Rhinoplasty | 39 (47%) | 44 (53%) | 83 (8.4%) |

| Age | |||

| 18-29 | 74 (52.9%) | 66 (47.1%) | 140 (14.3%) |

| 30-39 | 123 (67.2%) | 60 (32.8%) | 183 (18.7%) |

| 40-49 | 130 (57.5%) | 96 (42.5%) | 226 (23.1%) |

| 50-59 | 94 (40.7%) | 137 (59.3%) | 231 (23.6%) |

| 60-69 | 47 (29.4%) | 113 (70.6%) | 160 (16.4%) |

| 70+ | 11 (28.9%) | 27 (71.1%) | 38 (3.9%) |

| Total | 479 (49%) | 499 (51%) | 978 (100%) |

Male patients had a higher frequency of abnormal tests (74.2%), while 49.5% of women had abnormal tests (p<0.0001). Abnormalities were more frequent in ASA 2 patients (83.8%) (p<0.0001), patients with comorbidities (59.6%), patients undergoing rhytidoplasty surgery (66.7%) and blepharoplasty (60. 9%), in patients aged between 60 and 69 years (70.6%) and patients over 70 years (71.1%). The mean ages of rhytidoplasty and blepharoplasty patients were 57.7 and 54.8 years, the highest among the surgeries.

Table 2 provides the exams separated by category and the number of abnormalities found. The tests were subdivided into 11 categories to facilitate the analysis: complete blood count (hemoglobin, hematocrit, leukocyte, and erythrocyte); coagulogram (platelet, TAP, KPTT, clotting time, bleeding time, and fibrinogen); cardiac (echocardiogram, exercise test, and echocardiography); renal (urea and creatinine); glycemia; thyroid (TSH, T4); hepatic (TGO, TGP and GT gamma); lipidogram (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, LDL); beta-hCG and HIV; chest x-ray and others (infrequent tests).

| Exams | Normal | Abnormal | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood count (Hb, hematocrit, leukocytes) | 3378 (97%) | 103 (3%) | 3481 |

| Coagulogram (platelets, TAP, KPTT, TC, TS and fibrinogen) | 3106 (96.9%) | 100 (3.1%) | 3206 |

| Cardiac (echocardiogram, test treadmill and echocardiography) | 1160 (85.9%) | 191 (14.1%) | 1351 |

| Renal (urea and creatinine) | 1189 (95.7%) | 53 (4.3%) | 1242 |

| Glycemia | 801 (88.3%) | 106 (11.7%) | 907 |

| Thyroid (TSH; T4) | 513 (93.4%) | 36 (6.6%) | 549 |

| Hepatic (TGO, TGP and GT range) | 480 (95.8%) | 21 (4.2%) | 501 |

| Lipidogram (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, LDL) | 342 (76.2%) | 107 (23.8%) | 449 |

| Beta hCG and HIV | 220 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 220 |

| Chest X-ray | 99 (99%) | 1 (1%) | 100 |

| Others | 61 (70.9%) | 25 (29.1%) | 86 |

| Total | 11349 (93.9%) | 743 (6.1%) | 12092 |

Others: HbA1c; albumin; abdomen ultrasound; angiotomography; myocardial scintigraphy; T3; spirometry; carotid ultrasound. TAP: Prothrombin activation time; KPTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time; TC: Clotting time; TS: Bleeding time; TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone; TGO: Oxaloacetic transaminase; TGP: Glutamic pyruvic transaminase; gamma-GT: Gamma glutamyl transferase; HDL: High density lipoprotein; LDL: Low density lipoprotein; Beta hCG: Beta chorionic gonadotropin; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

In total, 12,092 exams were analyzed, resulting in an average of 12.3 per patient. Exams in the blood count and coagulogram categories were the most performed (55.3% of the total exams). Only 6.1% of the exams (n=743) showed abnormalities. The lipidogram exams had the highest frequency of abnormality (23.8%), but it corresponded to 6.4% of patients with this abnormality, given that the same patient had more than one abnormal exam.

Table 3 shows the types of comorbidities present in the patients and the control tests performed in the preoperative period for these comorbidities, according to the guidelines of Brazilian societies17,18,19,20. The control test (blood pressure) was performed during the physical examination of all patients with systemic arterial hypertension. Thyroid-related comorbidities were the most common (n=180; 18.4%), with 178 cases of hypothyroidism and 2 cases of hyperthyroidism. Among patients with diabetes (n=41), 97.5% (40/41) performed only the blood glucose test, pointing to hyperglycemia in 70% (28/40) of these. Glycated hemoglobin (Hba1c) dosage was performed in 8 patients. Of these, only one had a result outside the recommended limits, but his surgery was performed without delay.

| Comorbidities | No. of patients | Control exam | Exams performed | Values out of recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid | 180 (18.4%) | TSHa | 95 (52.7%) | 16 (16.8%) |

| SAH | 145 (14.8%) | Blood pressureb | 145 (100%) | 26 (17.9%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 139 (14.2%) | LDLc | 20 (14.3%) | 6 (30%) |

| Mental disorder | 132 (13.4%) | - | - | - |

| Pulmonary | 44 (4.4%) | - | - | - |

| Diabetes | 41 (4.1%) | Glycemiad | 40 (97.5%) | 28 (70%) |

| Labyrinthitis | 29 (2.9%) | - | - | - |

| Hypotension | 27 (2.7%) | - | - | - |

| Coagulopathy | 14 (1.4%) | Coagulogram | 14 (100%) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Heart disease | 13 (1.3%) | Cardiac | 12 (92.3%) | 6 (50%) |

| Obesity | 9 (0.9%) | - | - | - |

| Others | 80 (8.1%) | - | - | - |

Table 4 shows the changes in conduct taken in the preoperative period from the performance and release of the EPO results. In 57/978 (5.8%) of the cases, there was some type of change in preoperative management, and 19/57 (33.3%) of them were related to the resolution of a urinary tract infection (UTI) or the upper airways (URTI). In 18/57 (31.5%) cases, additional tests were requested to expand the investigation. In 14 cases, the investigation did not lead to any other conduct; in two cases, it resulted in the introduction of treatment, and in two others, in a new diagnosis for the patient. For 23/57 cases (40.3%), it was unnecessary to change the scheduled date of surgery to carry out the conduct, whereas in 33 cases (57.9%) it was necessary to postpone the surgery date. There was only one case (1.8%) of surgery cancellation due to worsening disc herniation. Thus, in our study, for 96.5% of the patients, performing EPO did not change the surgery planning.

| Conduct / Status | Not postponed | Postponed | Canceled | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection Resolution (UTI/URTI) | 14 | 5 | 0 | 19 (33.3%) |

| Performing additional tests without other additional conduct | 2 | 12 | 0 | 14 (24.6%) |

| Medication adjustment or prescription | 3 | 8 | 0 | 11 (19.3%) |

| Diagnosis of new disease | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 (7%) |

| Referral to physician specialist | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 (5.3%) |

| Additional exams resulting in new treatment | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (3.5%) |

| Additional exams resulting in a new diagnosis | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (3.5%) |

| Aggravation of previous illness | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (3.5%) |

| Total | 23 | 33 | 1 | 57/978 (5.8%) |

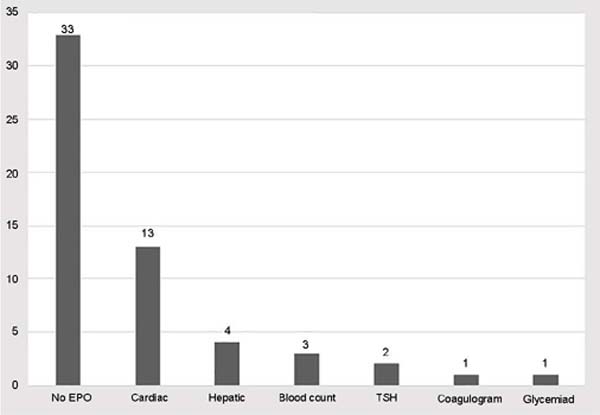

Abnormalities in only 6 types of EPO resulted in a change in preoperative conduct; 33/57 conducts (57.9%) were carried out only with data from anamnesis and physical examination; that is, no data from another examination was necessary. Among the exams in general, the one that most contributed to changes in behavior was the cardiac exam (n=13; 22.8%) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

The request for routine EPO, which exams to order, and how the results of EPO can impact the decision to take conduct for the operative and postoperative period in elective surgeries is still controversial. Our study presents data from Brazilian patients and differs from other studies by describing the most frequent abnormalities of routine EPO requested for a population of patients considered to be at lower risk compared to other types of surgery.

The appearance of abnormal results is common in routine exams12, and the vast majority of these results are of no clinical importance and do not have the power to predict any complication or operative or postoperative risk12. The appearance of an abnormal EPO result (which may be a false-positive result) induces the physician to investigate this abnormality, postponing the surgery and exposing the patient to more unnecessary tests and stress12. On the other hand, it should be borne in mind that cosmetic surgeries that do not involve treatment of an active disease must be performed with maximum safety and, being purely elective, can be postponed when the responsible physician deems it necessary.

The performance of routine EPO in healthy patients of surgeries considered less invasive, such as aesthetic plastic surgery15, is more controversial since it is a low-risk procedure with few complications21,22. According to the guidelines of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) (2012)7 and the National Institute for Health And Care Excellence (NICE) (2016)8, requesting tests for healthy patients (ASA 1 and ASA 2), which perform minimally invasive surgeries, should be minimal.

The exams should be based on the findings of the clinical consultation that require a deeper investigation, which may indicate a real risk to the patient in the perioperative period so that this patient can be correctly managed7,8. Clinical evaluation, which consists of anamnesis and physical examination, is considered the most important part of the preoperative evaluation. Data obtained from it, such as age, clinical history, surgery to be performed, ASA classification, and even physical exercise capacity, are considered the best predictors of perioperative morbidity12.

There is a preference for anesthesiologists to perform the preoperative evaluation, and, according to some studies, anesthesiologists were more efficient in ordering EPO, performing a smaller number of exams, and maintaining the quality of the evaluation, therefore, saving more in performing the tests. EPO23,24.

In our study, the average EPO performed per patient was 12.3 exams. Due to the study design, it was not possible to access the clinical history of each patient; therefore, it was not possible to accurately define whether the EPO rate was outside the guideline recommendations. However, the number of exams was observed to be higher than recommended. In the study by Mantha et al.,25 patients received an average of 10.9 EPO per patient, and in the study by Reazaul Karim et al.26, there was an average of 7.1 EPO per patient.

Considering that our study individualized each exam within the blood count and coagulogram, it is possible to say that the number of EPO performed in the present study is within the range identified by these other two authors, who studied routine EPO in other elective surgeries. According to the study by Srivastava & Kumar27, 30% to 60% of the requested EPO are above the proposed recommendations, and 60% to 75% of outpatient surgery patients would not need to undergo EPO if there is an adequate clinical evaluation.

Comparing the findings with other studies in the literature that also address the request for routine EPO in patients undergoing elective surgeries, the number of patients with exam abnormalities in our study is within the expected range (51%). The studies by Fischer et al.22 and Benarroch-Gampel & Riall28, respectively, found an abnormality rate of 36.7% and 61.6%.

Regarding the tests with the highest percentage of abnormality, those performed more selectively (category “Others”) showed the highest abnormality, followed by the lipidogram, cardiac assessment, and blood glucose. However, the predominant abnormality was the cardiac evaluation (18.4%). Santos et al.1 found that ECG abnormality was the most frequent among patients (36.8%), agreeing with our study regarding the type of exam. In the studies by Fischer et al.22 and Reazaul Karim et al.26, the exams with the most abnormalities were the blood count, which had a low frequency of abnormalities in our study.

Regarding age, the rate of abnormal tests to be higher in the “60-69” years and “70+” years was expected, as elderly people usually have more test abnormalities and comorbidities than other age groups22. Male patients had a significantly higher rate of abnormal EPO than female patients, mainly abnormal blood glucose and ECG. This finding has not been described in any other study. There was no difference between age and the number of patients with comorbidities in each group, possibly due to other factors such as lifestyle habits.

Performing routine EPO generally does not lead to changes in conduct for the perioperative period, and some authors indicate that only between 0% and 9% of these tests induced a change in management in elective surgeries28. In our study, 5.7% of the patients had some preoperative conduct abnormality, but in only 2.4% of the total number of patients, the change was due to some EPO abnormality. Only 24/12,092 requested exams (0.1%) were responsible for changing the preoperative conduct.

It should be noted that there were 14 cases of “performing additional tests without further action,” showing that a deeper investigation was carried out based on a suspicion found by the physician, but which did not lead to any positive result; 11/14 cases occurred due to an abnormal result examination, which may indicate false-positive tests. Therefore, it was observed that only 13/24 EPOs that led to a change in behavior were beneficial for the patient. In the study carried out by Mantha et al.,25 17 EPO with the indication of request and 8 exams without indication provoked a change in preoperative conduct, only 4 exams of those considered without indication (0.2% of the total of exams performed) caused beneficial conduct for the patient, who was the treatment or counseling of diabetes.

Our study also provides an assessment of how patients manage comorbidities. The values of the control tests for comorbidities must be within the acceptable range since, if they are abnormal, they can increase the chances of perioperative morbidity, especially diabetes and hypertension29,30. It was found that 70% of patients were outside the recommendations of the Brazilian Society of Diabetes20. The frequency of dyslipidemia was also relevant, but it should be noted that the lipidogram is not mentioned in any guideline, and its request is not necessary as EPO.

The most frequent comorbidities found in our patients were thyroid disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, mental disorder, lung disease, and diabetes. In other studies with patients undergoing various elective surgeries, the most frequent were: hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and lung disease1,5,22,31. Notably, these authors do not mention mental disorders in their studies, but when it comes to aesthetic plastic surgery, it is important to mention this subject. The frequency of depression in plastic surgery patients can be up to 5 times higher than in the general population32.

The study has some limitations related to its design. The retrospective study was carried out using a database, which did not allow access to the patient’s clinical history. Thus, the study could not investigate whether any recommendations or actions were taken after hospital discharge due to an abnormal EPO. To evaluate the data found, it should be considered that the vast majority of cases were women who underwent elective plastic surgery. Thus, the frequency of some comorbidities and other findings is related to the studied sample. Additionally, it was not possible to identify which physician was the applicant for the abnormal EPO.

CONCLUSION

Abnormalities were found in 6.1% of the total number of tests requested, and 51% of the patients had at least one abnormal EPO. The frequency of abnormal EPO was significantly higher in men, older people, and surgeries in patients with a higher mean age. Abnormalities in cardiac exams were the most frequently found. The performance of EPO changed the preoperative conduct for 3.4% of patients, mainly causing the postponement of plastic surgery. Attention should be paid to the patient’s comorbidities, as 70% of the people with diabetes studied had blood glucose above the recommended level.

In the context of plastic surgery, there may be fear about the legal issue, which may increase the number of requests for exams as a form of medical protection. However, it should be noted that the literature and societies discourage tests without their own indication. On the other hand, patient safety should be prioritized, given that it is an elective surgery and can be postponed.

For future studies, it is suggested to study the indications of each examination performed in greater depth and obtain detailed data on the preoperative consultation, given that the topic is still scarce in the literature. Additionally, conduct studies correlating the exams with the pre- and postoperative periods in aesthetic plastic surgery.

1. Faculdade Evangélica Mackenzie do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

2. Hospital Lipoplastic, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

Corresponding author: Renato Nisihara Rua Padre Anchieta, 2770, Curitiba, PR, Brazil Zip Code: 80730-000 E-mail: renatonisihara@gmail.com

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter