Case Report - Year 2023 - Volume 38 -

Augmentation mammoplasty and autologous fat transplantation: an alternative for the treatment of hypomastia and mild pectus excavatum - Case report

Mamoplastia de aumento e transplante de gordura autóloga: uma alternativa para o tratamento da hipomastia e pectus excavatum leve - Relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Pectus excavatum (PE) is a congenital chest deformity characterized by deep depression in the sternum. Autologous fat transplantation has been used for aesthetic purposes, mainly on the face, and has recently gained relevance in thoracic and breast surgeries. The present study aims to present a case of mild PE associated with hypomastia. A 24-year-old female patient attended the consultation for breast augmentation due to hypomastia, but the clinical examination also revealed an associated mild PE that the patient did not notice. Surgical planning included breast augmentation and autologous fat transfer. A 260ml silicone breast implant was used, and 250ml of fat was injected in the sternal region and the lower medial contour of the breasts. There were no complications during the 12-month follow-up period. The combination of augmentation mammoplasty and fat transplantation in treating PE deformity proved to be a minimally invasive, good, safe option with high patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Funnel chest; breast implants; Lipectomy; Mammaplasty; Thoracic wall

RESUMO

Pectus excavatum (PE) é uma deformidade torácica congênita, caracterizada como uma depressão profunda no esterno. O transplante autólogo de gordura tem sido utilizado para fins estéticos, principalmente na face, e recentemente ganhou relevância nas cirurgias torácica e das mamas. O objetivo do presente estudo é apresentar um caso de PE leve associado a hipomastia. Uma paciente de 24 anos compareceu à consulta para mamoplastia de aumento por hipomastia, mas o exame clínico também revelou um PE leve associado que não foi percebido pela paciente. O planejamento cirúrgico incluiu a mamoplastia de aumento e a transferência de gordura autóloga. Foi utilizado um implante mamário de silicone de 260ml, e uma quantidade total de 250ml de gordura foi injetada na região esternal e no contorno medial inferior das mamas. Não houve complicações durante o período de acompanhamento de 12 meses. A associação de mamoplastia de aumento e transplante de gordura no tratamento da deformidade de PE revelou-se uma opção minimamente invasiva, boa, segura e com alta satisfação da paciente.

Palavras-chave: Tórax em funil; Implantes de mama; Lipectomia; Mamoplastia; Parede torácica

INTRODUCTION

Congenital chest deformities affect both genders and, in general, manifest as changes in the chest wall, such as pectus excavatum (PE)1, associated or not with muscle deformities as in Poland’s syndrome2. Losses and limitations are more significant when affecting women due to aesthetic aspects2. In these patients, breast asymmetry is the most frequent reason for consultation, despite any other problem that may be associated3.

Clinical presentation ranges from mild to severe defects, which may be associated with cardiopulmonary dysfunction1 2 3; in these cases, extensive thoracic surgical corrections may be necessary4. However, when the deformity is mild or moderate, other surgical resources such as custom-made silicone implants5, cartilage fragments, local flaps, tissue expansion, etc.6 can be used.

Autologous fat transplantation has been used for aesthetic purposes, mainly on the face, and has recently gained relevance in breast and thoracic surgeries7. Despite the variation in the resorption rate in the first three months after transplantation, Ho Quoc et al.8 highlighted that a learning curve is an important point for greater stability of the result. Since autologous fat transplantation presents stable long-term results in small deformities, low cost, low rate of complications1, 9, and the possibility of repeating the procedure, its use for reconstructive and aesthetic purposes has been considered, including thoracic deformities and mammary.

OBJECTIVE

Therefore, the study aims to present a case of mild pectus excavatum associated with hypomastia in a patient who presented for a breast augmentation appointment.

CASE REPORT

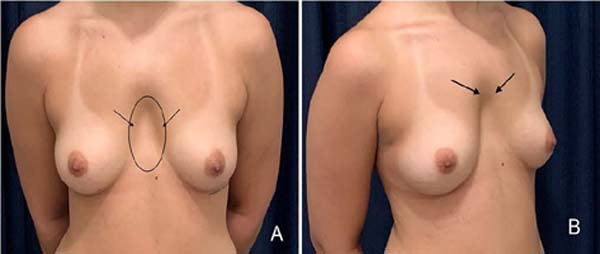

A 24-year-old female patient attended the consultation for breast augmentation due to hypomastia, but the clinical examination also revealed the presence of mild pectus excavatum (PE), which the patient had not noticed (Figure 1). The cardiopulmonary physical examination was normal. Likewise, the chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, and blood count were within normal limits.

The proposed surgery included subglandular breast augmentation and autologous fat transfer to treat the thoracic deformity and improve breast contour. The area to be aspirated was previously marked in the infraumbilical region of the abdomen. The patient was placed in dorsal decubitus, and after general anesthesia, 500ml of saline solution with adrenaline was injected subcutaneously.

Syringe-assisted liposuction was performed with a 3.5 mm cannula, and the same volume was aspirated (tumescent liposuction). The manipulation of the fat to be transferred was less traumatic as possible, and only a saline solution was added to remove excess blood. Then, the fat was decanted into 20ml syringes.

A 5cm incision was made in the inframammary fold. After subglandular dissection with electrocautery, subglandular augmentation mammaplasty was performed bilaterally with a 260ml round nanotextured breast implant, and the wound was closed in layers.

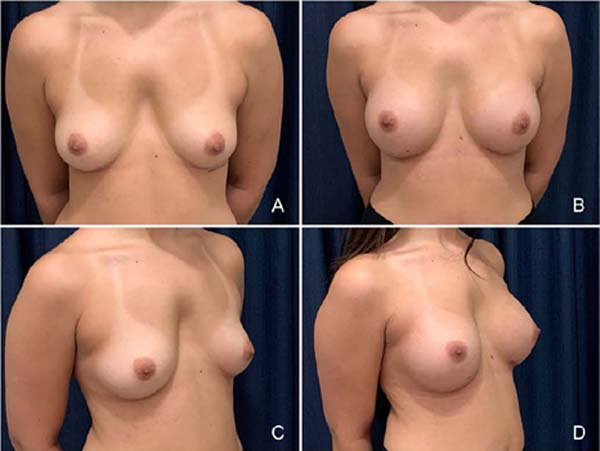

The fat transplant was performed with a 2mm cannula in different paths and depths (in a fan shape) through the incision in the inframammary fold to improve the medial contour of the breast. A 2 mm incision was made in the anterior region of the chest (at the level of the xiphoid process) to treat the pectus excavatum deformity. These trajectories were crossed with each other to treat the defect (Figure 2) better.

A total volume of 250ml of fat was injected as follows:

50ml in the inferior-medial contour of each breast (total of 100ml).

150ml in sternal deformity to correct pectus excavatum (PE).

The follow-up period was 12 months. No minor or major complications were reported, and a second procedure was not required.

Pre- and postoperative aspects of the result after 12 months are shown in Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

Thoracic deformities can be acquired or congenital, such as Poland’s syndrome and pectus excavatum1 2 3 4 5 6,9. According to Snel et al.5, untreated PE can lead to embarrassment and psychosocial problems, especially in more severe deformities.

Changes in breast contour seem to be the main reason for consultation in most female patients with mild thoracic deformities2, 3. In the case presented, hypomastia was the patient’s main complaint, and the diagnosis of pectus excavatum was made during the clinical examination.

Ho Quoc et al.3 highlighted that in cases of associated thoracic and breast deformities, breast augmentation alone could increase the thoracic deformity, compromising the postoperative result and generating dissatisfaction on the part of the patient. This fact reveals the importance of a good clinical examination for adequate preoperative surgical planning to achieve the best postoperative result. Thus, in the case presented, the surgical planning sought to treat both defects: hypomastia and pectus excavatum, simultaneously.

Different approaches and techniques have been described for the treatment of pectus excavatum6. However, the best choice will depend on the severity of the malformation and the surgical experience of the team.

Since the improvement of the use of autologous fat injection by Coleman10, the technique has been widely disseminated and studied by several authors, including its use in aesthetic and reconstructive surgeries8. Delay & Guerid7 stated that breast fat grafting is likely to greatly improve the results of thoracic malformations, including pectus excavatum. Schwabegger6 recommended the technique for adults with good nutritional status. Therefore, in this case, the option for autologous fat transplantation occurred because it is a mild defect and is considered a simple and minimally invasive option that avoids any need for implantation or bone remodeling in the sternal region.

The ways of collecting and treating the fat to be grafted have been the subject of clinical and experimental studies. More recently, fat enrichment has been investigated to guarantee more stable and, consequently, more predictable results. Hamed et al.11 carried out an experimental study using erythropoietin for fat enrichment, which resulted in greater integration in the transplanted site.

Tanikawa et al.12 demonstrated that enriching adipose tissue with stromal cells promoted better integration and maintenance of long-term results in patients with microsomia. However, despite the good results, the major limitation of these studies is the short follow-up period and the fact that many researchers still question the potential complications of stem cell therapy.

The rate of absorption of the transplanted fat is quite variable and is related to the total volume transferred7. Many authors had recently described stable results, with low complication rates when fat grafting was compared to other procedures9. Ho Quoc et al.3 reported a low resorption rate in treating pectus excavatum with fat grafting, obtaining a satisfaction rate of approximately 95% for both patients and the surgical team. Another advantage is the possibility of repeating it to improve the result or correct small residual deformities8.

A second procedure was unnecessary in the case presented during the 12-month follow-up period. We consider that overcorrection of the deformity prevented a second procedure, following what was stated by Pereira & Sterodimas1, who consider overcorrection important in a procedure with variable resorption rates. However, despite the same authors highlighting that lasting results in the sternal region are unpredictable1, Ho Quoc et al.3 described a natural and stable long-term result.

CONCLUSION

The presented case showed the importance of clinical examination and preoperative planning for better results. Otherwise, just the correction of hypomastia could accentuate a mild pectus excavatum, initially not noticed by the patient. Thus, combining augmentation mammoplasty and autologous fat transplantation to treat PE proved to be a good option, minimally invasive, safe, and with high patient satisfaction. However, it is important to inform that fat grafting procedures in the sternal region may present reabsorption, and additional procedures may be necessary.

1. Universidade de Franca, Faculdade de Medicina, Franca, São Paulo, Brazil

2. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Disciplina de Cirurgia Plástica, São Paulo,

São Paulo, Brazil

Corresponding author: Marcus Vinícius Jardini Barbosa Alameda dos Flamboyants, 700, Morada do Verde, Franca, S P, Brazil. Zip code: 14404-409 E-mail: drmbarbosa@gmail.com.br

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter