Original Article - Year 2023 - Volume 38 -

Immediate bilateral breast reconstruction after skin-sparing mastectomy: cross-sectional incision and implants in mixed plane

Reconstrução bilateral imediata de mamas pósmastectomia preservadora de pele: incisão transversal e implantes em plano misto

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Complications in immediate breast reconstruction after skin-preserving mastectomies are recurrent. The authors describe conduct to reduce them and improve the anatomical/esthetic result using implants. The objective is to reduce the incidence of areolar necrosis, improve breast projection in reconstructions with submuscular implants, recover partial or total sensitivity, and facilitate symmetrization.

Method: The mastectomy involves a lateral transverse incision from the areolar border to the armpit. Repair with implants included in a mixed plane by divulsion of the pectoral muscle, dividing it into two portions in the direction of its fibers, the association of the serratus muscle fascia and inferior/lateral subcutaneous tissue, and/or pectoralis minor muscle in the superolateral area. The incision is sutured when there is no breast ptosis or superimposed by de-epidermization of one of the borders, which may include a reduction in diameter and relocation of the areola. Or fusiform de-epidermization of the periareolar skin and medially to it. The contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy had a similar procedure, improving symmetry.

Results: 106 patients (212 breasts) were operated on with satisfactory results and complications due to infection, positioning of the implants on the learning curve, and surface irregularities.

Conclusion: Immediate breast reconstruction after skin-preserving mastectomy by the proposed method is a possible option, obtaining good breast symmetrization and projection, return of sensitivity, and absence of total necrosis of the areola.

Keywords: Breast; Prostheses and implants; Mammaplasty; Breast Neoplasms; Reconstructive surgical procedures

RESUMO

Introdução: Complicações nas reconstruções imediatas de mamas pós-mastectomias preservadoras de pele são recorrentes. Os autores descrevem conduta para redução delas e melhoria do resultado anatômico/estético utilizando implantes. O objetivo é reduzir a incidência de necroses areolares, melhorar a projeção das mamas nas reconstruções com implantes submusculares, recuperar a sensibilidade parcial ou total e facilitar a simetrização.

Método: A mastectomia é realizada com incisão transversal lateral, do bordo areolar à axila. A reparação com implantes incluídos em plano misto por divulsão do músculo peitoral, dividindo-o em duas porções na direção de suas fibras, associação da fáscia do músculo serrátil e tecido celular subcutâneo inferior/lateral, e/ou músculo peitoral menor na área superolateral. A incisão é suturada quando não há ptose mamária, ou superposta por desepidermização de um dos bordos, podendo incluir redução do diâmetro e relocação da aréola. Ou desepidermização fusiforme da pele periareolar e medialmente a ela. A mastectomia contralateral redutora de riscos teve procedimento semelhante, melhorando a simetria.

Resultados: Foram operadas 106 pacientes (212 mamas) com resultados satisfatórios e complicações por infecção, posicionamento dos implantes na curva de aprendizado, e irregularidades de superfície.

Conclusão: Reconstrução imediata das mamas pós-mastectomia preservadora de pele pelo método proposto é opção possível, obtendo boa simetrização e projeção das mamas, retorno da sensibilidade e ausência de necrose total de aréola.

Palavras-chave: Mama; Próteses e implantes; Mamoplastia; Neoplasias da mama; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos

INTRODUCTION

The first description of the attempt to repair the mastectomy area with a latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap dates back to the end of the 19th century, carried out by Tanzini in 19061. After 19812, the aggressiveness of the treatment of breast tumors was reduced, preserving muscles, skin, sometimes the nipple-areolar complex (NAC), and part of the gland. It was reconstructed after quadrantectomy and radiotherapy intraoperatively or later.

After 1991, skin-sparing mastectomies, and sometimes NAC, in cases without lymph node metastasis that did not require radiotherapy, received immediate repair and incision changes3. With the improvement of implants, they became an option in the arsenal of tactics. They allow for less surgical time, quick recovery, lower hospital costs, and patient acceptance.

The symmetry is not adequate in a breast receiving an implant, and the contralateral breast corrected with its own tissues. Moreover, there is a description of an incidence of 7.3% of occult ductal carcinoma and 4.6% of lobular carcinoma “in situ” in this breast4 and a cumulative risk of appearance of 0.5 to 1% each year of life5. In the presence of BRCA1/2 and a family history of breast cancer6, contralateral subcutaneous mastectomy (risk reduction) may be indicated, repairing it with an implant. The permanence of this breast, risk reduction7, and better symmetry and aesthetics are the patient’s decision8,9.

Post-mastectomy repair has intercurrences, under any approach, occurring even in experienced hands (34.64%)10. Removing tissues close to the NAC, either by necessity or prevention, reduces periareolar vascularization, with eventual necrosis.

If the skin and subcutaneous coverage are less than 1.5/2.0cm thick, inserting the implant in the supramuscular plane is not ideal. It is recommended to place it under the pectoral muscle and serratus anterior, but the projection of the reconstructed breast is reduced by muscle pressure. Furthermore, implant displacement in the cranial direction may occur, causing discomfort during muscle contraction or lateral-inferior displacement.

Moreover, breast emptying causes reduced sensitivity.

OBJECTIVE

The objective is to describe tactics as an attempt to reduce the incidence of areolar necrosis, improve breast projection with submuscular implants, subjectively analyze the recovery of tactile breast sensitivity and objectively the painful one, and facilitate symmetrization.

METHOD

This is a retrospective study of cases with an analysis of medical records.

Those referring to unilateral mastectomy were excluded, including expanders and subsequent repair, late reconstructions, immediate or late reconstructions with flaps, secondary repairs, and hygienic mastectomies.

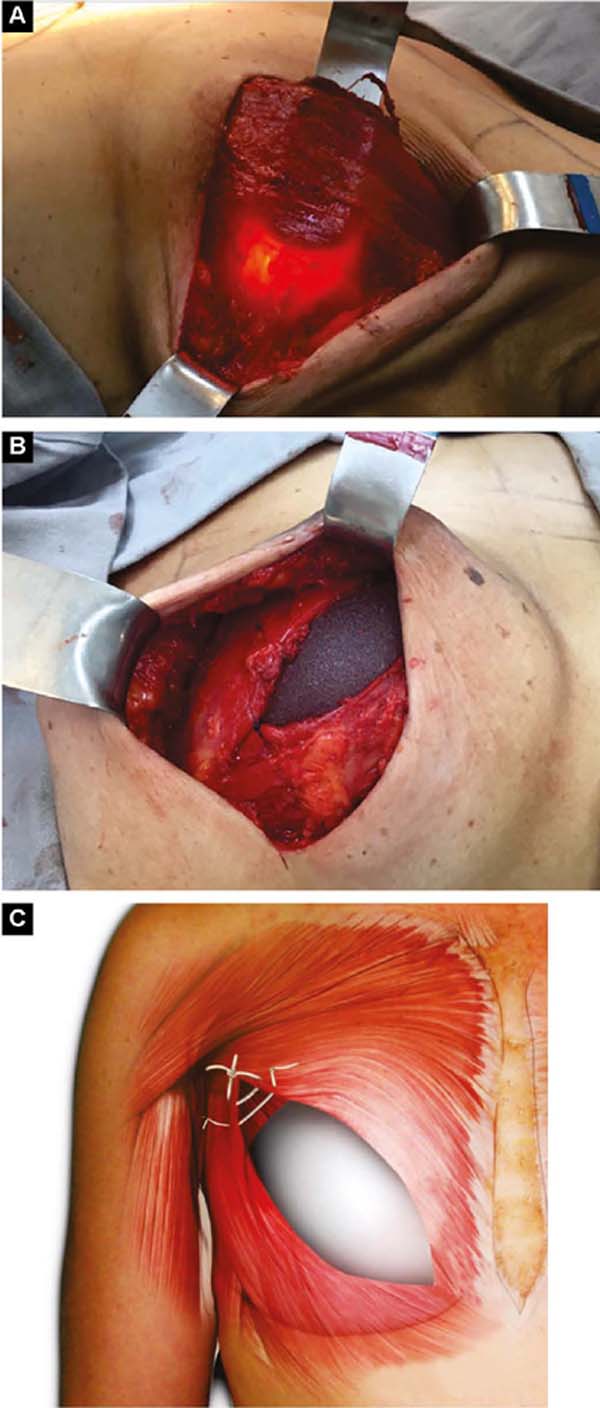

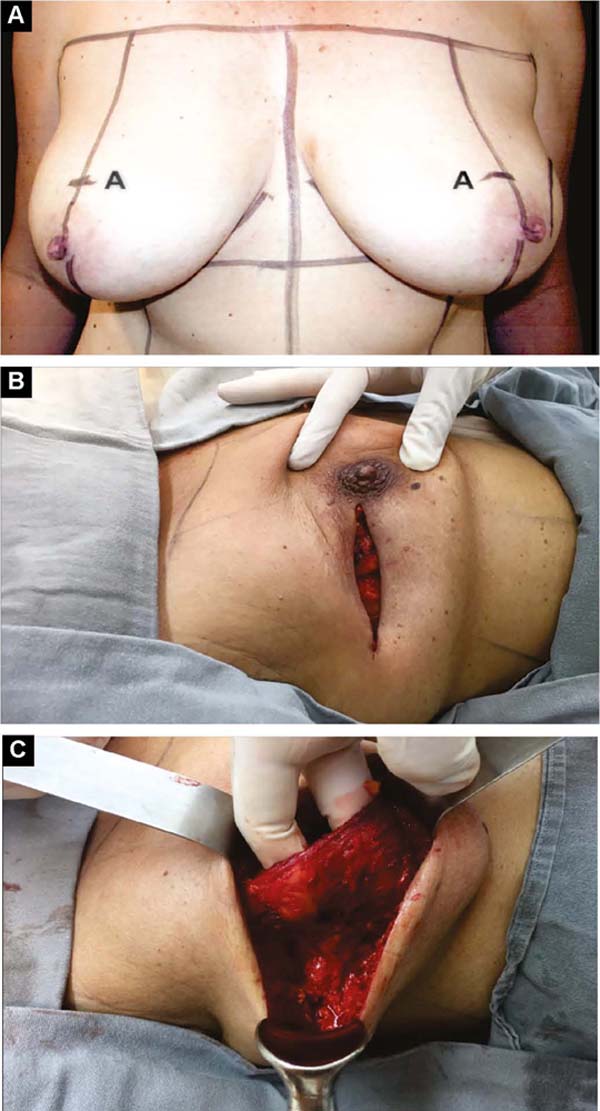

With the patient standing, mark the breast lines that form the quadrilateral where the implant’s base will be located (Figure 1A)11. The mastectomy is performed with a transverse incision from the lateral border of the areola to the axillary region, taking advantage of it to detect and remove the sentinel node or axillary dissection (Figure 1B).

In the detachment of the glandular tissue, the thickness of the skin and subcutaneous tissue must be homogeneous and decreasing, from the base of the breast to the papilla, without prejudice to the oncological treatment. If there is breast ptosis, the incision is curved with caudal concavity.

After oncological procedures, with no lymph node emptying, the pectoralis major muscle is divulsed obliquely in the direction of the fibers in half its width (Figure 1C), gently detaching it with the index finger. In the inferior caudal and medial direction, an electric scalpel is used, going beyond the submammary fold (HLBL) by 2 centimeters, elevating along the anterior aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis muscle, making three vertical incisions in it, loosening its constriction.

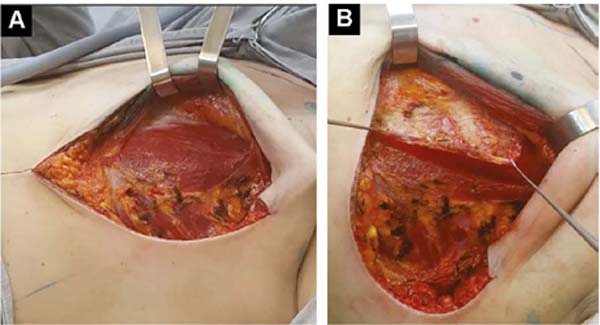

Upwards, it is shifted up to 1.5cm below the superior horizontal mammary line and paramedially to the medial vertical mammary line 1.5cm from the mid-external line11, similarly to what is used in breast augmentation by some authors12,13,14. Laterally, the entire pectoral muscle is detached until the aponeurosis of the serratus anterior muscle is found. Ahead, it is detached, including muscle fibers, added to the loose subcutaneous tissue over the delicate aponeurosis, together up to the vertical lateral breast line (VLBL)11, sufficient to obtain the lateral and inferior contour of the pocket and accommodate the implant (Figure 2A).

This is lodged between the two strands of the pectoral muscle. In its outline, the implant is covered by the muscle, and in the center, it is free to protrude and obtain a better base/height ratio15 (Figure 2B). To prevent their retraction during healing, gentle traction stitches with absorbable sutures are placed between the divulsed strands in the superolateral half over the implant (Figures 2B and 2C).

If the pectoralis minor muscle has good extension and volume, the pectoralis major is moved medially from its lateral border, and the minor one laterally to the vertical lateral breast line (VLBL), reinforcing the superolateral part of the pocket (Figures 3A and 3B).

After introducing the implant, the lateral edge of the pectoralis major is sutured to the medial edge of the pectoralis major.

The skin and subcutaneous tissue on the side of the thorax, detached from the breast during the mastectomy, are fixed to it with separate absorbable sutures16,17.

Three options for final skin closure will be determined by the excess amount preoperatively.

First: A subdermal and skin suture is performed without initial ptosis (AM from 0 to 2cm). If the ptosis is small (AM of 3/4cm)11, the lower part of the flap is de-epithelialized and sutured to the lateral edge of the pectoral muscle, reinforcing the superolateral coverage of the implant.

Second: With medium ptosis (AM of 4/5cm) and need to relocate or reduce the areolar diameter, in addition to the procedure described in the first option, the excess in the periareolar region is marked, the areola is de-epidermized and repositioned.

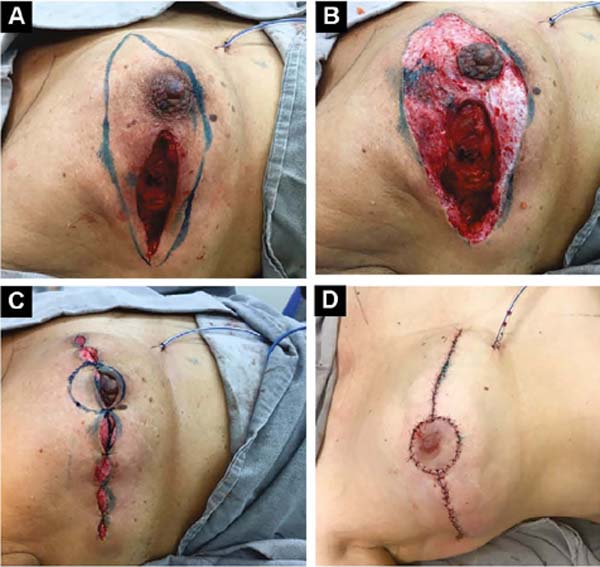

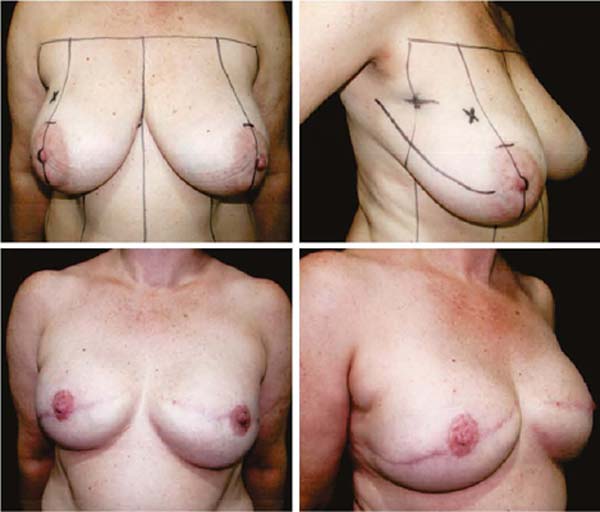

Third: With large ptosis (MA greater than 5cm)11, a transverse spindle is marked using a bidigital grip around and medially to the areola. Its diameter is demarcated, and the de-epidermized area is the new areolar site (Figures 4A, 4B, 4C and 4D).

The closure of de-epidermized areas should be performed with a few simple sutures separated subdermal with absorbable threads, not strangling the circulation, allowing areolar and periareolar irrigation. The dermis that folds under itself protects the implant and gives the breast greater projection. The skin is sutured with separate non-absorbable stitches, gentle traction, and constriction.

Vacuum drainage of the subcutaneous pocket is necessary until the daily volume drained is less than 30 ml/24 hours. The end of the drain is placed in the axillary region and extruded in the inferior medial pole (Figure 4D). The same procedure is performed on the contralateral breast for symmetrization and risk reduction.

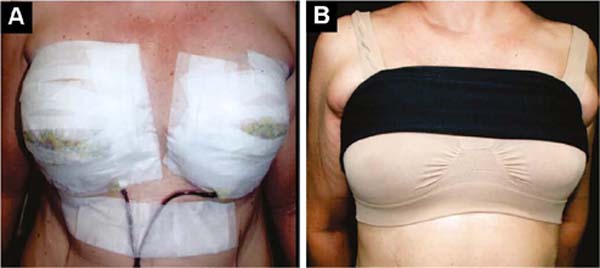

The initial bandage covers the incisions with insulating ointment, and the breast is covered with a microporous tape bra, which remains and is retouched until the stitches are removed, around 12 days (Figure 5A).

From the first day onwards, a delicate, seamless, slightly compresswive bra is applied over it, plus a bandage that slightly compresses the implants in the caudal direction, preventing their displacement upwards, until the formation of the fibrous capsule in 2 months (Figure 5B).

RESULTS

One hundred six patients (212 breasts) were operated on in the same surgery as the skin-preserving and contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy, using the tactics described, from June 2009 to July 2019. The patients are from a private clinic and signed an Informative Consent and Enlightening.

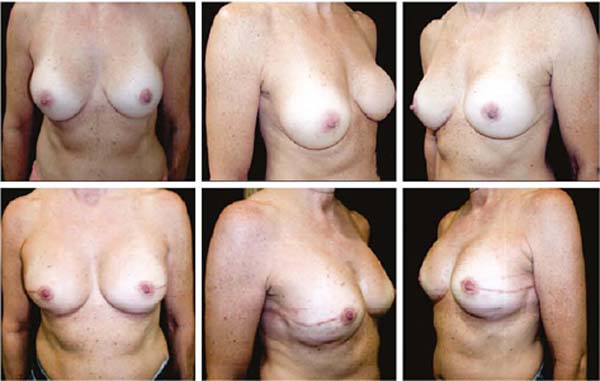

Figures 6A, 6B, 6C, 6D, 6E and 6F; 7A, 7B, 7C, 7D, 7E and 7F; 8A, 8B, 8C, 8D, 8E and 8F; 9A, 9B, 9C, 9D, 9E and 9F are from patients who underwent surgery with good results.

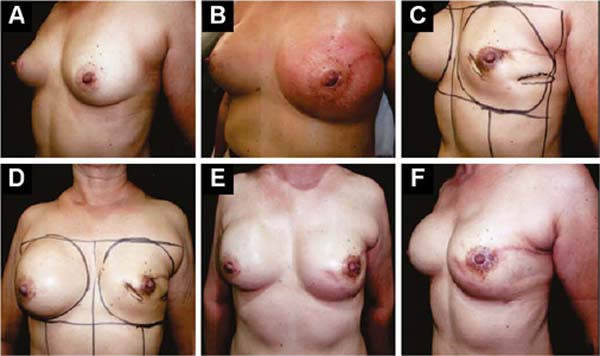

Three patients had inflammatory signs and seroma after one month (Table 1). In two, the drained liquid was subjected to three cultures. Of these, the first two were negative, and the third, in a different laboratory, detected S. epidermidis. The third patient had a positive result in the first culture. The implant was removed and reoperated after four months in all three cases. The fibrotic tissue was removed, and a new implant was inserted (Figures 10A, 10B, 10C, 10D, 10E, and 10F). All of them presented late moderate capsular contracture.

| 106 Patients - 212 Breasts | |

|---|---|

| Surface irregularity | 25 - 23.58% |

| Seromas | 3 - 2.83% |

| Post-trauma seroma | 1 - 0.94% |

| S. Epidermidis infection | 3 - 2.83% |

| Bruises | 1 - 0.94% |

| Areolar necrosis | 1 - 0.94% |

| Dehiscence of sutures | 2 - 1.88% |

| Tall implants | 2 - 1.88% |

| Contralateral breast tumor | 5 - 4.71% |

| Complications and inadequate results | 35.82% of patients and 17.91% of breasts |

One patient presented late seroma after three months due to trauma, drained for one week, without vacuum, and use of anti-inflammatory drugs. The resolution was satisfactory. One case of hematoma was treated clinically. Only one patient had marginal, partial areolar necrosis in the lower half, with spontaneous healing. In this case, the lateral incision contoured the areola inferiorly to the medial pole.

Two patients had skin suture dehiscence. In one, the de-epidermized area protected the implant, and healing was spontaneous. On the other, the muscle was exposed and was solved with an elastic bandage18,19 (Figures 11A, 11B, and 11C and Figures 12A, 12B, 12C, 12D, 12E, and 12F).

The implant was positioned high 2 months postoperatively in two initial cases.

Surface irregularity was the most frequent bad result (25 cases).

The projection obtained was always similar to breasts in good shape.

Perfect symmetry depended on regularity in the “post-mastectomy flap” thickness, which was more easily obtained when it was homogeneous bilaterally.

Tactile sensitivity was analyzed at 2/6 months, with the examiner and the patient lightly sliding fingers over the breast. The painful one with the tip/cannon of the needle pressing against the skin in the quadrants determines it hurts/does not hurt without the patient’s vision. The partial or total return was constant and variable, smaller and later the thinner the mastectomy skin remnant20.

DISCUSSION

Before puberty, the subcutaneous tissue over the breast buds is thickly homogeneous. The hormonal stimulus depends on the serum level, the elastic quality of the skin, and the number of buds. The breasts, as they grow, more or less distend the skin and reduce the thickness of the subcutaneous tissue from its periphery in the thorax to the NAC. This is the main cause of various breast shapes and volumes based on the extent of the base and projection of the breast. Preserving it with decreasing thickness is convenient, remaining vessels and nerves that form the superficial vascular and nervous network up to the papilla essential to reduce circulatory deficiency and return sensitivity.

The removed breast volume is measured and placed in a 2000ml graduated bottle containing 1000ml water. The added tissue collaborates with the choice of implant volume, disregarding the axillaries removed in association with the mammary.

Based on the existing breast, the patient discusses the convenience and possible volume in the preoperative period. The remaining skin, the thorax’s lateral and vertical extension, and the major pectoralis muscle must be considered.

Ptosis measurement is not the only parameter that determines the extent of scarring; the volume of the implant also.

After three cases of late infection by S. epidermidis, the skin was routinely re - sterilized, the pocket was washed with saline solution after the mastectomy, and no further cases occurred.

Two patients, 2 months after the operation, had high implants, despite being well positioned in the surgical act at the beginning of the use of the tactic. The approach was modified using a transverse band on the upper mammary poles and relaxing incisions on the aponeurosis of the rectus muscle.

In tumors close to the skin in quadrants other than the lateral ones, requiring resection, the spindle was performed in the direction from the base of the breast to the areola. In the axilla, a transverse incision was made in the same direction, obtaining the sentinel node. Depending on the ptosis, the procedure joins the two incisions or not, with de-epidermization.

When the areola was removed, the procedure was similar, and its repair was postponed to another surgical procedure or tattoo. Alternatively, if there were excesses, immediately redone with a graft from the contralateral areola; this breast always had a flatter apex than the contralateral one, requiring posterior fat grafting.

It is convenient to carry different volumes of implants to decide which one will be used during the reconstruction. Contralateral subcutaneous mastectomy, in general, was more tissue conservative, and the volume used was often smaller.

The tactic described made it possible to eliminate total necrosis of the areola, even if the periareolar region had minimal subcutaneous tissue after the mastectomy.

The transverse incisions provide good scars, and together with the preserved thickness of the subcutaneous tissue, they recover partial or total breast sensitivity between two months and two years20.

All 106 patients operated on using this technique received the procedure on the contralateral side, aiming at symmetrization. This is not easy to obtain. Five patients had an undiagnosed tumor in the contralateral breast.

In the postoperative period, the fear of mutilation due to the loss of the breast is replaced by a feeling of relief and enthusiasm when obtaining breasts that are many times more adequate than those before the surgery. This fact facilitates the acceptance of chemotherapy with possible hair loss. Removal of the contralateral breast also caused a feeling of relief.

Patient satisfaction with having performed the contralateral mastectomy ranges from 84 to 96%7,8, but it depends on the quality of the result obtained. These were better in patients with small tumors and without the involvement of axillary nodes. It is then possible to preserve the thicker and more homogeneous subcutaneous fatty tissue without removing the areolas.

When there was a positive sentinel node, predicting possible radiotherapy, a skin expander was included for breast repair and contralateral mastectomy after the end of treatment. Nevertheless, the symmetrization results did not reach the same quality.

In the surface irregularities caused by the mastectomy, a second procedure was necessary to perform correction with a fat graft, improving the results. Discussing the need for a second surgical procedure in advance is convenient.

The tactic of leaving the pectoralis major muscle open, in addition to providing greater projection of the breast, eliminates the discomfort of pressure due to muscle contraction. And, in the long term, possible costal alterations.

Immediate reconstruction with implants became the authors’ best option. However, late reconstructions with donor areas of adequate volume are the ones they prefer.

Considering 212 breasts operated on in 106 patients, the total incidence of complications or unsatisfactory results was 17.91% of the breasts or 35.82% of the patients, the most prevalent being surface irregularities.

CONCLUSION

Immediate breast reconstruction with transverse incision and implants in a mixed plane after skin-preserving mastectomy and contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy is another possible option. It allows good projection, reduction of areolar necrosis, and partial or total return of tactile/painful sensitivity, facilitating symmetrization.

1. Faculdade Estadual de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto, Divisão de Cirurgia Plástica,

São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil

Corresponding author: Antonio Roberto Bozola Avenida Brigadeiro Faria Lima, 5544, Vila São José, São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 15090-000 E-mail: ceplastica@hotmail.com

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter