Case Report - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Calcinosis in an area of late burn: a case report and management discussion

Calcinose em área de queimadura tardia: relato de caso e discussão da conduta

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Cutaneous calcinosis is a rare disease characterized by the precipitation of calcium crystals in the skin tissue. It can be localized, generalized, dystrophic, metastatic, iatrogenic, or idiopathic.

Case Report: Female patient, 66 years old, victim of second and third-degree burns by fire in the lower abdomen and thighs at 8 years old, reaching 25% of the body surface. After 58 years, she was diagnosed with dystrophic calcinosis in the burn scar, which was confirmed through biopsy and histopathological analysis. She underwent surgical excision associated with rotation of the upper abdomen dermal-fat flap and total skin graft for scar correction.

Conclusion: Although the best therapeutic choice is still unclear, treating complications leading to functional disability is essential to reduce morbidity and increase the patient's quality of life.

Keywords: Calcinosis; Burns; Wound healing; Keloid; Skin and connective tissue diseases.

RESUMO

Introdução: Calcinose cutânea é uma doença rara caracterizada por precipitações de cristais de cálcio no tecido cutâneo. Pode ser localizada ou generalizada, distrófica, metastática, iatrogênica ou idiopática.

Relato do Caso: Paciente feminina, 66 anos, vítima de queimaduras de segundo e terceiro graus por fogo em abdome inferior e coxas aos 8 anos de idade atingindo 25% de superfície corpórea. Após 58 anos, recebeu o diagnóstico de calcinose distrófica na cicatriz da queimadura, contemplado através de biópsia e análise histopatológica. Submetida a exérese cirúrgica associada a rotação de retalho dermogorduroso de abdome superior e enxertia de pele total para correção de cicatrizes.

Conclusão: Embora a melhor escolha terapêutica ainda não seja clara, o tratamento de complicações que podem culminar em incapacidade funcional é fundamental para reduzir a morbidade e aumentar a qualidade de vida do paciente.

Palavras-chave: Calcinose; Queimaduras; Cicatrização; Queloide; Doenças da pele e do tecido conjuntivo.

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous calcinosis is a rare disease characterized by the precipitation of calcium crystals in the skin tissue1. According to the phospho-calcium balance, it can be classified as dystrophic, metastatic, iatrogenic or idiopathic1.

The dystrophic form is the most common1-3; there are no laboratory alterations in the serum levels of calcium and phosphorus or visceral involvement. The metastatic type occurs in normal tissues due to increased calcium and/or phosphate serum levels.4 The iatrogenic manifestation results from intravenous extravasation of calcium gluconate and deposition of calcium salts in the skin after electromyography or electroencephalography5. On the other hand, idiopathic occurs in the absence of tissue and metabolic changes4.

Calcinosis can be localized (tissue damage due to trauma, inflammation, infection, necrosis or neoplasia) or generalized (associated with collagenosis, genodermatoses and some types of panniculitis)2.

CASE REPORT

Patient AGC, female, 66 years old, born in Marau - Rio Grande do Sul. Victim of burn with fire in abdomen and thighs at 8 years of age, reaching, at the time, approximately 25% of the body surface, with second and third-degree burns. She remained hospitalized for approximately 3 months in the city of origin, undergoing serial debridements and partial skin grafts.

In the first year after the burn, she already had scar retractions in the lower limbs, with difficulty in abduction and ambulation, having developed shortening of the left leg. In 2005, the patient reported the appearance of hardened cartilage-like lesions amid scarred areas of childhood burns, starting only in the left thigh and progressing soon afterward to the lower abdomen.

A dermatological evaluation in November 2018 noted the presence of ulcerated lesions with corneal-keratotic material inside, erythema and significant induration of the edges of the lesions in the lower abdomen and left thigh. Due to the suspicion of Marjolin’s ulcer, a biopsy of the lesions was chosen.

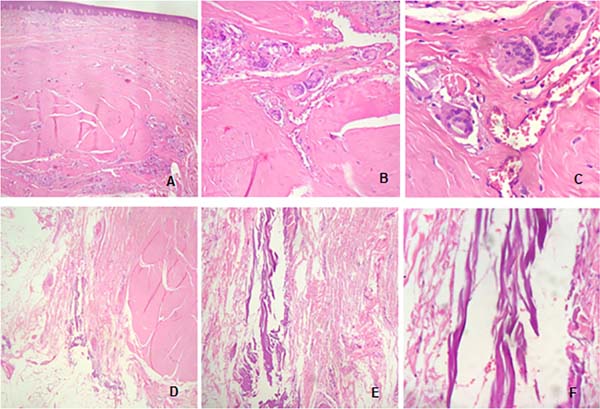

The anatomopathological examination of January 2019 indicated hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis associated with fibrinoleukocyte crust and dermal fibrosis, concluding the examination with no signs of malignancy and diagnosis of dystrophic calcinosis.

She was referred to the plastic surgery service of Hospital Universitário Evangélico Mackenzie in September 2019 for surgical excision of calcinosis that caused extreme aesthetic and functional discomfort for the patient. The surgical procedure was performed in November of the same year.

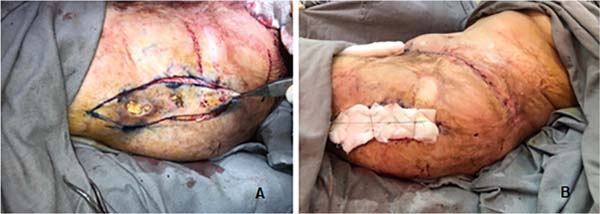

In the lower abdomen region, it was decided to treat burn sequelae together with resection of scarring fibrosis and areas of calcinosis with rotation of the upper abdomen dermofatty flap. In the lateral region of the left thigh, we opted for total skin grafting from the abdominal flap (Figures 1 to 5).

The material resected during the surgical procedure of the lower abdomen and left thigh region was sent for anatomopathological examination, with results of hypertrophic sclerosis associated with chronic and acute inflammation, in addition to areas of metaplastic ossification, with the absence of malignancy in both parts.

Preoperative laboratory tests showed calcium, phosphorus, CPK, aldolase, parathyroid hormone, total, direct and indirect bilirubin, urea, creatinine and prothrombin time within normal limits. Vitamin D was below the reference values. Antinuclear factor, anticentromere antibodies and antiscleroderma (SCL 70) were non-reactive, with negative antiSS A (RO) and antiSS B (LA).

The hemogram showed hemoglobin, leukocytes and platelets within the reference values. The hematocrit was below the reference values, and the rods were above. The 24-hour urine showed calcium within the normal range and a urinary volume of 1,200.00 ml.

The electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with an HR of 102 bpm. Chest X-rays showed normal transparency of the lungs, free sinuses, phrenic domes, and cardiac area within normal limits. The left thigh radiograph showed diffuse bone rarefaction, signs of severe coxarthrosis, with flattening deformity and femoral head sclerosis. The pelvic radiograph also showed diffuse bone rarefaction, in addition to left coxofemoral dislocation, with the displacement of the femur, superiorly, neoarticulating with the ileum and reduction of the right coxofemoral joint.

DISCUSSION

The etiology of calcinosis is still undefined, with several hypotheses described5. Although calcium and phosphate concentrations in tissues are close to their saturation levels, salt deposition is not common, thanks to local inhibitory mechanisms. Calcification may arise from some tissue alteration, even with normal serum levels. Changes in tissue structure, reduced vascularization, hypoxia, changes typical of aging, and genetic predisposition may be involved in forming calcium deposits in the skin5.

The most sensitive test for diagnosing the pathology is bone scintigraphy2, demonstrating calcium deposits in the tissues. However, it is the anatomopathological examination that confirms the diagnosis2.

Calcinosis can cause muscle atrophy, joint contractures and skin ulcers with recurrent episodes of calcium extrusion and purulent material from the lesion2,6. If the diagnosis is delayed, such complications can lead to painful and debilitating conditions, resulting in functional disability2,6.

The treatment of dystrophic calcinosis has variable results2,3,7. This difficulty in its approach stems from the low incidence of the condition and the variable and unpredictable natural history. Therefore, to date, there is no universally recognized therapy6.

The prescription of corticosteroids, diltiazem, colchicine, probenecid, aluminum hydroxide, bisphosphonates and anti-tumor necrosis factor, and surgical excision procedures, are described as possible therapies2,3,6,7. Small areas were successfully treated with warfarin, carbon dioxide laser, ceftriaxone and intravenous immunoglobulin8; in cases associated with connective tissue diseases and calciphylaxis, topical sodium and thiosulfate have been effective.

In the most extensive cases associated with burns, the areas of calcinosis were treated through surgical intervention, from the simple removal of the calcium deposit with tweezers, and the use of grafts, to the application of intralesional triamcinolone8. The results of these therapies are contradictory and consistent benefits have not been reported6.

In the case described here, the team chose not to initiate drug therapy due to the patient’s lack of systemic involvement and because her skin lesions remained stable during follow-up.

CONCLUSION

Calcinosis is an uncommon skin condition with underlying mechanisms not fully understood. There is a short description in the literature of calcinosis as a complication of burns3. Although the best therapeutic choice is still unclear, treating complications that may lead to functional disability is essential to reduce morbidity and increase the patient’s quality of life. Thus, the present study serves as a reference for future studies, aiming at further elucidation of the pathophysiological process of this correlation.

REFERENCES

1. Rosmaninho A, Carvalho S, Lobo I. Photoletter to the editor: Calcinosis cutis in a burn scar. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9(4):120

2. Ferrara FS, Souza BC, Alvarenga CO, Vidigal MR, Tebcherani AJ, Sanchez APG. Calcinose cutânea distrófica em adolescente: relato de caso. Rev Med (São Paulo). 2012;91(3):215-8.

3. Lee HW, Jeong YI, Suh HS, Lee MW, Choi JH, Moon KC, et al. Two cases of dystrophic calcinosis cutis in burn scars. J Dermatol. 2005;32(4):282-5.

4. Fabreguet I, Saurat JH, Rizzoli R, Ferrari S. Calcinose cutanée associée aux connectivites. Rev Med Suisse. 2015;11(466):668-72.

5. Carocha APG, Torturella DM, Barreto GR, Estrella RR, Rochael MC. Calcinose cútis distrófica universal associada a lúpus eritematoso sistêmico: um caso exuberante. An Bras Derm. 2010;85(6):883-7.

6. Castro TCM, Yamashita E, Terreri MTRA, Len CA, Hilário MOE. Calcinose na infância, um desafio terapêutico. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2007;47(1):63-8.

7. Shinjo SK, Souza FHC. Atualização na terapêutica da calcinose em dermatomiosite. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2013;53(2):211-4.

8. Lockwood KA, Oliphant T. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis within burns, successfully treated with excision and secondary intention wound healing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(5):648-9.

1. Hospital Universitário Evangélico Mackenzie, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

2. Faculdades Pequeno Príncipe, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

MCS Conception and design study, Conceptuali- zation, Final manuscript approval, Project Administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

LMPS Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Project Administration, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

RD Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Project Administration, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

RFF Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Project Administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

TBLS Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Project Administration, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author: Mariana Cionek Simões Rua Professora Ephigenia do Rego Barros, 63, Bairro Mercês, Curitiba, PR, Brazil. Zip Code: 80730-450, E-mail: mari_cionek@hotmail.com

Article received: August 12, 2021.

Article accepted: December 13, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter