Case Report - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Eyelid Xanthelasma: surgical treatment as the first choice

Xantelasma palpebral: tratamento cirúrgico como primeira escolha

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Eyelid xanthelasma is the most common form of cutaneous xanthoma, characterized by yellowish patches on the eyelid's skin. Despite being a benign condition and not presenting with functional limitations, it is an important aesthetic complaint that impacts the patient's social and emotional life. There are clinical therapeutic options, but the most widespread approach is the surgical approach with excision of the lesions, a simple procedure with few complications and lower local recurrence rates. This study aims to describe the surgical treatment of palpebral xanthelasma, to assess postoperative patient satisfaction and postsurgical recurrence rates.

Methods: This is a retrospective study with a sample of 25 patients undergoing surgical treatment of eyelid xanthelasmas. Postoperative follow-up was performed at intervals of 7 days, 30 days, 90 days and 12 months with an interview, physical examination and application of a questionnaire that included the identification of local recurrences, postoperative complications and satisfaction with the aesthetic result.

Results: Four patients evolved with local recurrence, and only two expressed dissatisfaction with the aesthetic result after the outcome. No patient who underwent surgical resection of lesions associated with autograft recurrence or dissatisfaction with the aesthetic result was observed.

Conclusions: Surgical treatment as the first option in the therapeutic approach of eyelid xanthelasmas should be considered, given the aesthetic and psychological impact of such a condition. It is a simple technique, easy to apply and reproducible, effective, and safe, with relevant satisfaction rates and low recurrences.

Keywords: Blepharoplasty; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Hypercholesterolemia; Xanthomatosis.

RESUMO

Introdução: O xantelasma palpebral é a forma mais comum de xantoma cutâneo, caracterizado por placas amareladas localizadas na pele das pálpebras. Apesar de ser uma condição benigna e não cursar com limitação funcional, é uma importante queixa estética que tem impacto na vida social e emocional do portador. Existem opções terapêuticas clínicas, mas a abordagem mais difundida é a cirúrgica com excisão das lesões, procedimento simples, com poucas complicações e menores taxas de recidivas locais. O objetivo deste estudo é descrever o tratamento cirúrgico do xantelasma palpebral, avaliar a satisfação dos pacientes no pós-operatório e as taxas de recidivas pós-cirúrgicas.

Métodos: Trata-se de um estudo retrospectivo realizado com uma amostra de 25 pacientes submetidos a tratamento cirúrgico de xantelasmas palpebrais. O acompanhamento pós-operatório foi realizado em intervalos de 7 dias, 30 dias, 90 dias e 12 meses com entrevista, exame físico e aplicação de questionário que contemplaram identificação de recidivas locais, complicações pós-operatórias e satisfação com o resultado estético.

Resultados: Quatro pacientes evoluíram com recidiva local e apenas dois pacientes manifestaram insatisfação com o resultado estético após o desfecho final. Em nenhum paciente submetido a ressecção cirúrgica das lesões associadas à autoenxertia foi observada recorrência ou insatisfação com o resultado estético.

Conclusões: O tratamento cirúrgico como primeira opção na abordagem terapêutica dos xantelasmas palpebrais deve ser considerado, visto o impacto estético e psicológico de tal afecção. É uma técnica simples, de fácil aplicação e reprodutibilidade, eficaz, segura, com relevantes taxas de satisfação e baixa ocorrência de recidivas.

Palavras-chave: Blefaroplastia; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Hipercolesterolemia; Xantomatose.

INTRODUCTION

Eyelid xanthelasma is a type of cutaneous xanthoma characterized by yellowish patches on the eyelid’s skin. Despite being considered a benign condition and not presenting with functional limitations, it is an important aesthetic complaint with a significant impact on the social and emotional life of the patient1.

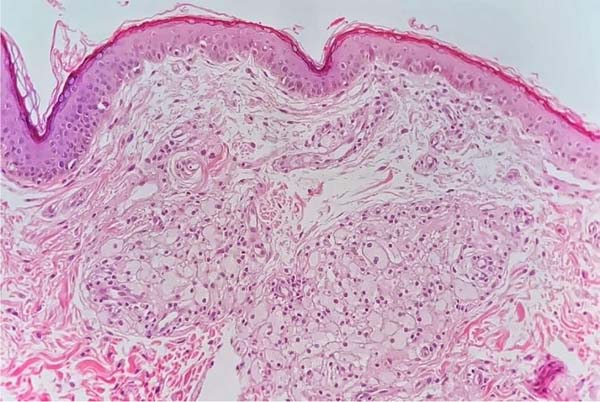

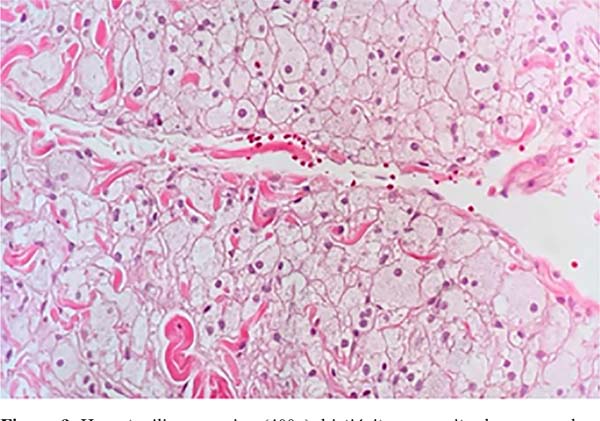

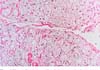

Xanthomas are formed by fibroproliferative connective tissue with intracellular deposition of cholesterol in histiocytes present in the superficial and middle layers of the dermis, which are called foam cells due to the microscopic appearance of their cytoplasm (Figures 1 and 2). Cholesterol deposition occurs mainly in perivascular regions2. They are associated with primary hyperlipidemias and those secondary to hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, drugs, and a diet rich in fat and alcohol3.

It is the most common form of cutaneous xanthoma, affects approximately 1.4% of the population, predominates in women and has a peak incidence in the age group between 30 and 50 years1. Clinically, it appears as yellowish plaques whose consistency can be soft, semi-solid or hardened. They are usually symmetrically distributed in the medial region of the upper eyelids, but they can also occur in the lower eyelids.

According to Lee et al.2, patients with xanthelasma can be graded according to the location and extent of the lesions. Grade I are those with lesions in the upper eyelids only. Grade II are those with lesions that extend to the medial area of the eyelids. Grade III are carriers of medial lesions in the upper and lower eyelids. Grade IV patients have diffuse medial and lateral involvement of the upper and lower eyelids.

The diagnosis is essentially clinical, based on the history and characteristics of the lesions. In doubtful clinical conditions, skin biopsy of the lesions is indicated for histopathological study4. Xanthelasma can negatively affect patients’ quality of life, especially concerning aesthetics, which sometimes motivates the patient to seek the removal of the lesions.

The most widespread treatment is surgical, indicated in familial hyperlipidemia, involvement of the four eyelids and recurrences. The main approach is simple excisional surgery, but it can also be associated with blepharoplasty, medial epicanthoplasty, local flaps and total skin graft5-7.

Other treatment modalities are laser therapy, chemical cauterization with trichloroacetic acid, radiofrequency treatment, and cryotherapy. It is important to evaluate the lipid profile of patients since the presence of changes in lipoprotein levels is common, which must be addressed8.

Although several therapeutic options have been proposed for curative purposes, no method guarantees satisfactory results in all cases and high recurrence rates. According to Mendelson & Masson9, there is a 40% chance of recurrence after primary surgical excision, 60% after the second therapeutic approach, and up to 80% when all four eyelids are involved. The main disadvantages related to surgery are the need for local or systemic anesthesia, the presence of scar, postoperative infection and, more rarely, ectropion and local depigmentation. Especially concerning autografting techniques, complications such as retractions, infection, dyschromia, hematomas and the risk of necrosis of the grafted tissue have been described1.

The search for harmonious self-perception and aesthetic acceptance emerged in 2021 as an even more crucial factor when we contextualize the pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2. The mass confinement caused the migration of work paradigms with particular emphasis on the frontal and eyelid regions due to the ascending use of the image through virtual platforms associated with the imposition of masks in the work environment. These factors caused changes in the aesthetic perception of patients who paid more attention to the periorbital region. Admiration for body image is a key part of building well-being and is inherent to maintaining mental health, the latter being affected amid the chaos of the pandemic10. It is noted, therefore, that the current context determines a significant increase in the funding base that motivated the preparation of this study.

Despite the literature covering non-surgical therapeutic possibilities, there is a lack of studies that relate the procedures to low local recurrence rates. Thus, evaluating the results of surgical treatment, a strategy frequently used in Plastic Surgery services in Brazil, is necessary.

OBJECTIVE

The present study aims to analyze the rates of local recurrence of the surgical treatment of eyelid lesions resulting from the accumulation of cholesterol crystals. Specific objectives include assessing the quality of surgical treatment of eyelid xanthelasmas through patient satisfaction with the postoperative outcome.

METHODS

The study was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of the University Hospital of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (HU-UFJF), in Juiz de Fora-MG, under CAAE number 24710119.3.0000.5133. After approval, an active search was initiated for patients with eyelid xanthelasma undergoing surgical treatment by the Plastic Surgery Service of the HU-UFJF and Clínica Plastic Center from 2016 to 2019.

Therefore, this is a retrospective study in which the results of the surgical treatment of eyelid xanthelasmas were evaluated. This analysis was performed through an interview and physical examination, with the application of a questionnaire prepared by the authors, which included the patient’s profile, identification of local recurrences, postoperative complications and satisfaction with the postoperative aesthetic result.

Inclusion criteria were patients with eyelid xanthelasmas who underwent surgical resection of the lesions and who did not undergo any additional treatment after surgery. Exclusion criteria were patients who did not undergo surgical treatment, patients who reported having hereditary dyslipidemias and patients who underwent some complementary treatment after the extirpation of lesions.

The surgical procedure for excision of the xanthomatous lesions was carried out with the patient in the horizontal supine position with the head of the head slightly elevated (30°), under sedation and local anesthesia. Antisepsis was performed with aqueous chlorhexidine and placement of sterile surgical drapes, as well as dermographism with methylene blue. Local anesthesia was then performed, followed by a surgical incision, resectioning xanthomatous lesions, excess skin on the upper eyelids, and excess periorbital fat bags on the lower eyelid.

Some lesions were too extensive for simple sutures and approximation of the edges. In these cases, total skin autograft was performed, removed from the upper eyelid when free from xanthelasmas or the retroauricular region with direct suture of the donor area. After hemostasis, synthesis was performed with 5-0 or 6-0 nylon thread in a single plane.

After data collection, it was possible to carry out procedures for analysis of the results obtained and subsequent preparation of statistical data.

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistical techniques. The summary measures used were mean, standard deviation, and relative and absolute frequencies. Double-entry contingency tables were used to describe the association between the categorical variables. The calculations were performed using the free statistical program Jamovi version 2.0.

RESULTS

To obtain the desired sample, 25 individuals were approached, male and female, who underwent surgical treatment of Xanthelasma palpebrarum at the University Hospital - UFJF and Clínica Plastic Center. In the study composition, there was a predominance of females, with 22 individuals representing 88% of the sample and three male individuals (12% of the sample), in line with the epidemiological data available in the literature. Still, on a descriptive basis, the age of the patients ranged from 37 to 69 years, with a mean of 52.6 years. Patient grouping data were also analyzed regarding the type of procedure performed - upper eyelid or lower eyelid excision or both eyelids - followed by the evaluation of recurrence and satisfaction of each group.

Regarding the follow-up time, in the present study, the patients returned after 7 days to remove the stitches, then after 30 days for evaluation, mainly of the scar and eyelid symmetry, and at 90 days, postoperative photos were taken. Occasionally, after 12 months, the patient is reassessed as a postoperative follow-up.

Initially, in the analysis of the categories of excision of xanthomas, 14 participants underwent excision exclusively in the upper eyelid (56%); five participants exclusively submitted to lower eyelid excision (20%); and six patients who underwent excision of both eyelids - corresponding to grades III and IV by Lee et al.2, resulting in 24% of the sample. The relationship between the degree of eyelid involvement and the gender of patients is described in Table 1.

| Degree of palpebral involvement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both eyelids | Total | ||||

| No | Yes | ||||

| Sex | F | n | 17 | 5 | 22 |

| % | 77.3% | 22.7% | 100.0% | ||

| M | n | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| % | 66.7% | 33.3% | 100.0% | ||

| Total | n | 19 | 6 | 25 | |

| % | 76.0% | 24.0% | 100.0% | ||

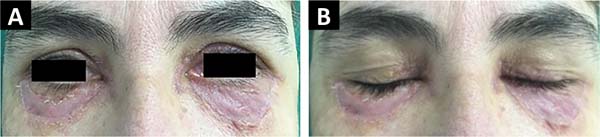

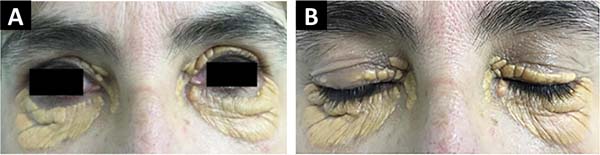

In two female patients, skin autograft was performed when the extension of the lesions exceeded the capacity of approximating the operative edges with a simple suture. They had involvement of both eyelids, but the grafts were performed in the lower eyelids, where there was a greater scarcity of skin. In both patients, excess tissue from the upper eyelid was used as a donor area (Figures 3 and 4).

In the analysis of recurrences after surgical interventions, four patients (16%), all female, had a recurrence of lesions. Among these, two patients underwent excision of cutaneous xanthomas in both eyelids. Patients who underwent skin autografts did not have recurrences, despite the literature description of a higher recurrence frequency in this group compared to the others.

Finally, in the analysis of participants’ satisfaction with the aesthetic result, only two manifestations of dissatisfaction were found after the final outcome, representing 8% of the total sample. In both female patients, we noticed the occurrence of recurrence after the excision of the eyelid xanthomas. Still dealing with individuals dissatisfied with the result, one patient underwent an approach in the upper and lower eyelids, and one underwent excision only in the lower eyelid.

However, it is important to note that the other patients who had recurrences (two participants) did not report dissatisfaction with the final aesthetic result. When approaching patients who underwent grafting, no recurrence or dissatisfaction with the aesthetic result was evidenced. Data related to xanthomas recurrences and patient satisfaction with the final aesthetic result are shown, respectively, in Tables 2 and 3.

| Satisfaction with the aesthetic result | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | ||

| Valid | No | 2 | 8.0 |

| Yes | 23 | 92.0 | |

| Total | 25 | 100.0 | |

| Relapse | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Valid | No | 21 | 84.0 |

| Yes | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Total | 25 | 100.0 | |

DISCUSSION

Considering the data obtained in the present study, it can be affirmed that eyelid xanthelasma occurs more frequently in women and middle-aged individuals, corroborating the descriptive information found in the literature. According to Zak et al.11, despite the lack of recent epidemiological data, the prevalence in females was about twice as high, occurring mainly in individuals over 50. This fact is justified by age-dependent dyslipidemia in 20-70% of patients with xanthelasmas, duly addressed in work by Bergman12.

The mechanisms involved in the development of xanthomatous lesions seem analogous to those involved in the early stages of atherosclerotic plaques1, with the formation of an inflammatory environment with an increase in T cells, macrophages and mediators such as COX, iNOX and MPO13.

Thus, when faced with an aesthetic complaint in the plastic surgery routine, the surgeon must pay attention to the possibility of the coexistence of congenital or acquired dyslipidemias, such as hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia.

In addition to significantly increased cardiovascular risk, the perpetuation of metabolic disorders is related to cases of recurrence and unsatisfactory esthetic results. Thus, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary, even if the initial complaint is purely aesthetic. Furthermore, the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chronic inflammatory cells in xanthelasma tissue has already been demonstrated, which suggests a possible potential for inflammation-modulating therapies in the management of skin lesions13.

Xanthelasma is a benign disorder, and there are rare reports of functional impairment, mainly due to increased plaque with visual field obstruction. Despite this, its cosmetic impact is undeniable, mainly due to the aesthetic importance of the periorbital region, which traditionally represents a complaint raised by patients. Therefore, in the literature, several methods aim to improve aesthetics, such as exclusive clinical treatment, trichloroacetic acid, laser ablation and surgical resection.

However, there are notable disadvantages resulting from non-surgical approaches that are not recommended in cases of extensive, deep, multifocal or recurrent lesions. Raulin et al.14, in their study of laser treatment with carbon dioxide, found a recurrence rate of 13%. This treatment modality presented significant complications, such as pigmentary changes and skin retractions in extensive lesions, discouraging its implementation in some services. Regarding clinical therapy, there is the use of Alirocumab, a monoclonal antibody, with a report of total regression in one patient15. As with laser ablation, these approaches are of low availability and high cost, discouraging their widespread use.

Concerning the surgical approach, the central theme of this study, some methods are described as definitive interventions for palpebral xanthelasma. le Roux16 describes a modified blepharoplasty technique in which the incision extends superiorly to involve the canthomedial area of the upper eyelid, where xanthomas are typically found. Hosokawa et al.17 described their technique of using musculocutaneous flaps to provide coverage after the excision of large lesions, preserving the upper eyelid skin for re-excision in case of recurrence.

Parks & Waller18 describe Theblepharoplastysimple as the main approach to the problem but advocate serial excision every two months in case of multiple injuries. Friedhofer et al.19 reported that in the case of small xanthelasma, which cannot be included in a blepharoplasty skin resection, simply because it was detached from the skin, it disappears completely. This occurs in small lesions, while in larger lesions, it evolves with a hypochromic spot without the lesion.

The study by Mendelson & Masson9 described the Mayo Clinic experience with 92 patients, showing a recurrence rate of 40% after simple primary excision and a recurrence rate of 60% after secondary excision. The highest incidence of recurrence was in the first year (26%). Our retrospective study identified a relapse rate of 16% in a sample of 25 individuals, representing a considerably lower rate than the Mendelson study. Mendelson & Masson still discourage the surgical approach in three specific situations: cases with familial hyperlipoproteinemia, involvement of all the eyelids and more than one recorded recurrence9. This study corroborates, in part, with Mendelson’s propositions since half of the sample that reported recurrence was surgically approached in both eyelids.

In the study by Kose6, 16 patients were followed up for up to five years, and all had bilateral involvement of the eyelids with extensive lesions. They underwent grafting, whose donor area constituted the upper eyelid after blepharoplasty. All patients in this study were satisfied with the aesthetic results, and only two had hyperpigmentation. A relationship is established between the therapeutic success obtained with grafting in the Kose study and the patients who underwent grafting in the present study: we obtained no recurrences, hyperpigmentation or retractions, in addition to aesthetically satisfactory outcomes according to the patients.

It is worth mentioning that in our study, the patients were followed up for 12 months postoperatively, with an interval shorter than the Kose interval for identifying possible unsatisfactory outcomes. However, the period of one year is considered an adequate time for the evaluation of pigmentation changes and retraction. Regarding identifying relapses, a longer follow-up period would be advantageous, but in the present study, we chose 12 months due to difficulties in returning the patient after this period.

Some authors already describe autograft after excision of extensive and deep xanthelasmas as a method of therapeutic choice since its accurate execution has obtained satisfactory aesthetic results6.

Other similar, more recent studies showed lower recurrence rates, which is close to the hypotheses raised in this work. The retrospective study by Lee et al.2, when analyzing 95 patients undergoing surgical excision of xanthelasmas - with simple excision, associated with blepharoplasty and myocutaneous flap composing the same sample - found only 3.1%, with no reports of postoperative complications or scar contractures.

In a national study, Bagatin et al.20 followed 40 patients for two years after they had undergone surgical excision of lesions, 10 of them in association with topical chemical treatment. In this study, 5% of patients had recurrence after one year of follow-up, and only 12% of the sample had complications such as scarring hypochromia.

Finally, regarding satisfaction with the result after the surgical approach, this study reached 92% of final satisfaction, which allows us to infer that the aesthetic outcome was predominantly accepted after the simple excision of xanthelasmas. Interestingly, two patients who reported relapses - half of the relapses in the study - also stated they were satisfied with their post-surgical appearance, which reinforces the hypothesis that, even in the face of the partial or total return of the lesions, surgical excision fulfilled the objective of providing aesthetic improvement.

Obradovic21 points to surgical excision as the first line of treatment after a clinical attempt, focusing on the premise of the high frequency of scar retractions and hyperpigmentation after non-surgical treatment with laser or topical acid, whereas, when properly performed and respecting the eyelid tension lines, few unsatisfactory results were reported by the surgical technique.

Considering that the simple excision of lesions is a procedure with low surgical risk, low rate of complications - if performed under adequate conditions of asepsis and good technical preparation of the team - and fast postoperative recovery, it can be recommended for individuals of different ages and patients with comorbidities that do not contraindicate its surgical performance. Furthermore, in the present study, relevant rates of satisfaction with the result and low occurrence of relapses were described, fulfilling one of the objectives of plastic surgery by restoring self-esteem and well-being to treated individuals.

CONCLUSION

It cannot be denied the significant aesthetic impact that eyelid xanthelasmas cause, either because of their location or the unsightly appearance of the plaques. Several non-invasive topical procedures are described, but the high recurrence rate and unsatisfactory outcomes have discouraged such techniques. It is concluded, therefore, that cosmetic surgery’s important role in treating palpebral xanthelasma is irrefutable since the technique is simple and easy to apply and reproducible, including in public and educational services, with results that demonstrate low rates of recurrence and high satisfaction in most patients.

REFERENCES

1. Nair PA, Singhal R. Xanthelasma palpebrarum - a brief review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;11:1-5.

2. Lee HY, Jin US, Minn KW, Park YO. Outcomes of surgical management of xanthelasma palpebrarum. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40(4):380-6.

3. Rohrich RJ, Janis JE, Pownell PH. Xanthelasma palpebrarum: a review and current management principles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(5):1310-4.

4. Laftah Z, Al-Niaimi F. Xanthelasma: An Update on Treatment Modalities. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2018;11(1):1-6.

5. Yang Y, Sun J, Xiong L, Li Q. Treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum by upper eyelid skin flap incorporating blepharoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37(5):882-6.

6. Kose R. Treatment of large xanthelasma palpebrarum with full-thickness skin grafts obtained by blepharoplasty. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17(3):197-200.

7. Pereira FJ, Cruz AAV, Guimarães Neto HP, Ludvig CC. Blefaroplastia associada a enxertia de pele autóloga para xantelasmas extensos: relato de caso. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2008;71(4):592-4.

8. Kavoussi H, Ebrahimi A, Rezaei M, Ramezani M, Najafi B, Kavoussi R. Serum lipid profile and clinical characteristics of patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(4):468-71.

9. Mendelson BC, Masson JK. Xanthelasma: follow-up on results after surgical excision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(5):535-8.

10. Kandhari R, Kohli M, Trasi S, Vedamurthy M, Chhabra C, Shetty K, et al. The changing paradigm of an aesthetic practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: An expert consensus. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(1):e14382.

11. Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158(2):181-8. DOI: 10.5507/bp.2014.016

12. Bergman R. Xanthelasma palpebrarum and risk of atherosclerosis. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(5):343-5.

13. Govorkova MS, Milman T, Ying GS, Pan W, Silkiss RZ. Inflammatory Mediators in Xanthelasma Palpebrarum: Histopathologic and Immunohistochemical Study. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34(3):225-30.

14. Raulin C, Schoenermark MP, Werner S, Greve B. Xanthelasma palpebrarum: treatment with the ultrapulsed CO2 laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1999;24(2):122-7.

15. Civeira F, Perez-Calahorra S, Mateo-Gallego R. Rapid resolution of xanthelasmas after treatment with alirocumab. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(5):1259-61.

16. le Roux P. Modified blepharoplasty incisions: their use in xanthelasma. Br J Plast Surg. 1977;30(1):81-3.

17. Hosokawa K, Susuki T, Kikui TA, Tahara S. Treatment of large xanthomas by the use of blepharoplasty island musculocutaneous flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;18(3):238-40.

18. Parkes ML, Waller TS. Xanthelasma palpebrarum. Laryngoscope. 1984;94(9):1238-40.

19. Friedhofer H, Ferreira MC, Tuma Junior P, Bonamichi GT. Tratamento cirúrgico dos xantelasmas associado à blefaroplastia. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plást. 1989;4(2):77-80.

20. Bagatin E, Enokihara MY, Souza PKD, Macedo FS. Xantelasma: experiência no tratamento de 40 pacientes. An Bras Dermatol. 2000;75(6)705-13.

21. Obradovic B. Surgical Treatment as a First Option of the Lower Eyelid Xanthelasma. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(7):e678-9.

1. Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Hospital Universitário, Juiz de Fora, MG,

Brazil

2. Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Faculdade de Medicina, Juiz de Fora, MG,

Brazil

3. Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Juiz de Fora, Departamento de Cirurgia Geral, Juiz

de Fora, MG, Brazil

4. Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Instituto de Ciências Exatas, Departamento

de Estatística, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil

5. Faculdade de Ciências Médicas e da Saúde de Juiz de Fora, Faculdade de Medicina,

Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil

MTD Analysis and/or data interpretation, Concep- tion and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/ or trials, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Prepa- ration, Writing - Review & Editing.

NVP Analysis and/or data interpretation, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/ or trials, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

GVD Project Administration, Realization of ope- rations and/or trials, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

AC Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Validation.

ASF Analysis and/or data interpretation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

ELC Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

LVD Conception and design study, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

TRRB Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author: Marilho Tadeu Dornelas Rua Dom Viçoso, 20, Alto dos Passos, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil. Zip Code: 36026-390, E-mail: marilho.dornelas@ufjf.br

Article received: June 21, 2021.

Article accepted: April 7, 2022.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter