Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 - Issue 4

Silicone breast prosthesis explant: breast reconstruction using the crossed flap technique

Explante de prótese mamária de silicone: reconstrução da mama pela técnica dos retalhos cruzados

ABSTRACT

Introduction: In 1963 Cronin and Gerow introduced the use of the silicone implant and its use increased exponentially. However, complications related to implants emerged over time. The set of adverse situations to the use of silicone implants fueled by the growth of social media culminated in an increase in the permanent removal of the implant. Many cases of explants have the inferior pedicle compromised by injury to the perforating vessels, and the crossed flap technique is an alternative for the reconstruction of explanted breasts.

Methods: Silicone explants were performed with immediate breast reconstruction without the use of a new implant, motivated by medical indication or the patients own desire. The crossed flap technique was used in all cases. It uses the crossing of parenchymal patches of the superior pedicle, one medial and one lateral, as described by Sperli.

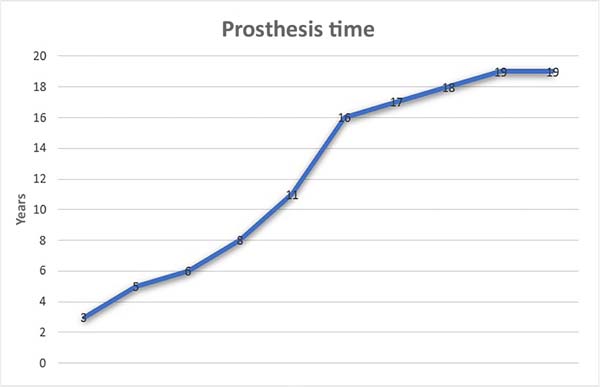

Results: 10 cases were operated from 2004 to 2021. The time of use of the prostheses ranged from 3 to 19 years and the main motivation for the explant was capsular contracture. No cases of necrosis were observed.

Conclusions: The crossed flap technique is a useful and safe alternative for breast reconstruction surgeries after definitive explantation.

Keywords: Autoimmune diseases; Lymphoma, large-cell, anaplastic; Quality of life; Implant capsular contracture; Breast implants; Breast diseases; Autoimmunity; Rupture; Mammaplasty; Breast neoplasms.

RESUMO

Introdução: Em 1963 Cronin e Gerow introduziram o uso do implante de silicone e seu uso aumentou exponencialmente. Contudo, complicações relacionadas aos implantes surgiram ao longo do tempo. O conjunto de situações adversas ao uso dos implantes de silicone, alimentado pelo crescimento das mídias sociais, culminou em um aumento da retirada definitiva do implante. Muitos casos de explante têm o pedículo inferior comprometido pela lesão dos vasos perfurantes e a técnica dos retalhos cruzados é uma alternativa para a reconstrução das mamas explantadas.

Métodos: Foram realizados explantes de silicone com reconstrução imediata da mama sem o uso de um novo implante, motivados por indicação médica ou por desejo próprio do paciente. A técnica dos retalhos cruzados foi utilizada em todos os casos. Ela se vale do cruzamento de retalhos parenquimatosos de pedículo superior, um medial e outro lateral, conforme descrito por Sperli.

Resultados: Foram operados 10 casos de 2004 a 2021. O tempo de uso das próteses variou de 3 a 19 anos e a principal motivação para o explante foi contratura capsular. Nenhum caso de necrose foi observado.

Conclusões: A técnica dos retalhos cruzados é uma alternativa útil e segura para as cirurgias de reconstrução da mama após explante definitivo.

Palavras-chave: Doenças autoimunes; Linfoma anaplásico de células grandes; Qualidade de vida; Contratura capsular em implantes; Implante mamário; Doenças mamárias; Autoimunidade; Ruptura; Mamoplastia; Neoplasias da mama.

INTRODUCTION

According to their genetic heritage, women worldwide are born with different shapes and sizes of breasts, a product of natural and cultural selection throughout human evolution. Multiple etiologies are reasons for these variations, and cases of hypomastia, ptosis and breasts that have suffered weight loss and lost volume are common.

Congenital deformities such as Poland’s syndrome, tuberous or asymmetrical breasts, and even the absence of a breast after mastectomy also comprise anatomical variations that began to receive attention with the evolution of plastic surgery.

Since 1985, with Czerny1, we have described operative techniques to treat anatomical variations of the breast by increasing its volume. In 1963, Cronin & Gerow introduced silicone implants to correct deformities, creating breast volume2. Since then, breast surgery using implants has increased exponentially. A race began to manufacture breast implants that marked breast surgery in the following years and established silicone, as it seemed inert, as the most appropriate material.

Guided by cultural phenomena and concepts of the beauty of a certain period and place, added to this set is the female desire for firm breasts with a well-defined shape and ideal size, even leading to breast reduction techniques with implants. The absence of volume or support was resolved, but complications related to the implants emerged over time.

Capsular contracture, aging of prostheses with leakage and migration of silicone gel, calcification of the fibrous capsule3 and “double-bubble” deformity4 are some of these disorders. There is also an association between the implant and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). In these cases, the replacement of the implant or its definitive removal, with, without or in association with capsulotomy and capsulectomy, are the main forms of treatment4.

In addition, since the 1960s, the association between systemic diseases and breast implants has been described. Perhaps the main one is Adjuvant-Induced Autoimmune Syndrome (ASIA), an autoimmune disease first described in 2011 and which has implant silicone as one of its etiologies5.

Recently, the set of nonspecific systemic symptoms associated with silicone implants came to be called “silicone disease” from the English “Breast Implant Illness,” although not yet fully proven and without registration as a disease by the World Health Organization (WHO) 6.

Thus, moving in the opposite direction to that seen previously, this set of adverse situations to the use of silicone implants, fueled by the growth of social media as a source of information for patients, culminated in an increase in the definitive removal of the implant7,8, sometimes by medical indication and, many times, by the patient’s desire and autonomy9.

The challenge, then, becomes the reconstruction of the explanted breast, which once took shape through content that no longer exists. The remaining autologous breast tissues become the main tool in this process.

The safest and most widespread way of filling the breast using autologous tissues is with the inferior pedicle flap10, described since the 1940s with Maliniac and used by most surgeons until today4,11. However, considering that the inframammary incision is preferred by most Brazilian surgeons (89.66%)4 in breast implant surgeries, many cases of explants have this inferior pedicle compromised by injury to the perforating vessels.

As an alternative, we must remember the crossed flaps technique for treating breast ptosis, initially described by Sperli, in 1972. It aims to restore the balance between breast content and continent and provide harmonic breast cones, eliminating the inferior pedicle12. Extending the indications of this technique to explanted breasts seems to be useful in the treatment of these patients.

OBJECTIVE

This paper aims to describe the use of the crossed flap technique for breast reconstruction after silicone prosthesis explantation.

METHODS

This is a retrospective study in which silicone explants were performed with immediate breast reconstruction without using a new implant, motivated by medical indication or the patient’s desire. Data were obtained from the medical records of the author’s private clinic, and the same surgeon performed all surgeries.

The characteristics of the population, time of use of the prosthesis, reasons for the explant and the presence of complications (dehiscence, seroma, necrosis, asymmetry, infection, hematoma, pathological healing) were verified. Follow-up was 6 months.

Inclusion criteria were patients undergoing silicone breast implant explantation with immediate reconstruction using crossed flaps without including a new implant.

Exclusion criteria were cases of explantation with prosthesis replacement, explantation with reconstruction through the association of other techniques in addition to crossed flaps, cases undergoing a second reconstruction procedure, and cases of explantation motivated by infection or hematoma, which could receive implants at another operative time due to patient’s wish.

Research subjects were informed, and consent terms were signed. This study followed the ethical requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki and its updates.

Operative tactic

The surgical program starts with the principles described by Pitanguy et al.13-15 in marking the skin, considering that there will be a loss of the content formed by the implant and that the continent formed by the skin will have to readjust after the explant.

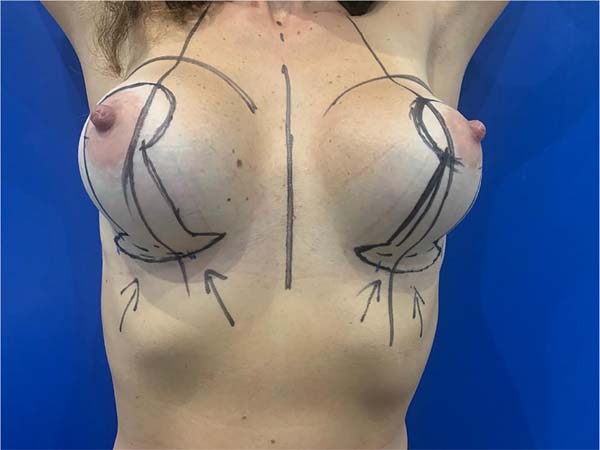

After de-epithelialization of the demarcated area (Figure 1), we incised the lower pole of the breast from the lower edge of the areola vertically to obtain two parenchymal flaps from the upper pedicle, one medial and the other lateral, as described by Sperli12.

At this moment, the prosthesis store is accessed, which may involve the subglandular, subfascial or submuscular space. We opted, preferably, for the dissection of the entire capsule for resection next to the implant. After removal, photographic and video records are made, and the pieces are sent for anatomopathological study. Then, we make release incisions on the outer edges of the flaps up to points “B” and “C,” respectively. With well-defined flaps, the simulation of the assembly of the breast with the crossing between them is performed (Figure 2).

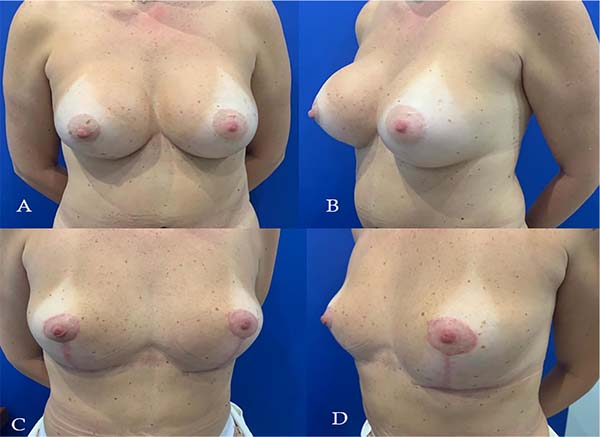

In each case, the rotation and crossing order of the lateral and medial flaps is free to reach the best conformation of the mammary cone. The fixation of the flaps will proceed in the best way so that the mammary cone is structured, in most cases with simple sutures between the tip of the flap that will cross first and the internal base of the second, followed by the rotation of the second flap over the first, suturing it to the base external of this. The anatomical plane of the previous breast pocket will not influence these maneuvers.

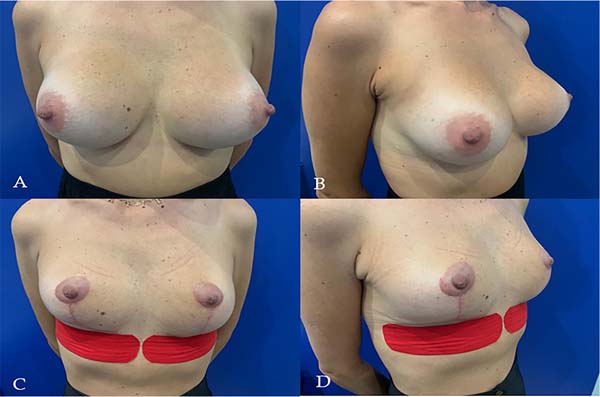

The final skin adjustment for the closure of the assembled breast and the definition of the position of the nipple-areolar complex will help to obtain a breast with a balance between the distribution of the remaining breast tissue content of the flaps in its skin continent (Figure 3).

Thus, we established a new breast with safe flaps, regardless of the incisions from previous surgeries for the breast implant. It is a science that we will always have a smaller volume, but with satisfactory aesthetic results, without high degrees of ptosis or the feeling of an empty breast.

RESULTS

Ten cases of explant reconstruction using crossed flaps were performed in female patients between 2004 and 2021. Ages ranged from 33 to 65 (Figures 4 and 5).

The diagnosed comorbidities were one case of heart disease, one of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, one of depression, one of diabetes mellitus, and two patients were former smokers.

Confirmed personal or family history of autoimmune disease was not verified in any patient. However, one of the patients had a positive antinuclear factor (ANA) but was still without a definitive autoimmune disease diagnosis.

The use time of the explanted prostheses ranged from 3 to 19 years (Figure 6).

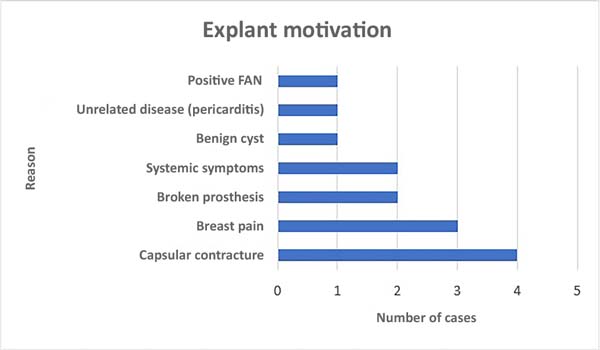

The reason for explant surgery, followed by reconstruction without a new prosthesis, was capsular contracture, followed by nonspecific breast pain. Some patients had more than one motivation (Figure 7).

As a complication, two cases of hypertrophic scars were easily treated using clinical measures (Table 1).

| Dehiscence | Seroma | Necrosis | Infection | Asymmetry | Bruise | Hypertrophic Scar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

DISCUSSION

The change in the perception of breast beauty is a dynamic process and has given value to smaller breasts. This and other influences that associate multiple diseases or symptoms with silicone, added to common indications for implant replacement, seem to be the reason for an increase in the number of patients who opt for the definitive explant. Social media emerged as a strengthening element of this phenomenon.

When inserted in a breast, the silicone implant almost always leads to a process of tissue expansion of the tissues surrounding the breast pocket, in different degrees15. With the removal of this prosthesis, flaccid tissues remain, without a well-defined shape and with the sensation of lack of breast volume. The balance between the continent and breast content is lost. For these cases, the redistribution of autologous tissues must be well understood to restore the breast cone safely from the flaps.

Several techniques have been developed to provide the breast with satisfactory shape and volume, reducing the rate of complications16.

The use of crossed flaps was improved by Sperli12, Hakme et al.17 and Miró18. It can redistribute tissue without using medial or inferior pedicles. Therefore, it proved useful in cases of explantation, where these pedicles tend to be compromised by the previous surgeries4.

Turner et al.19 show the usefulness of fat grafting for filling breasts with little breast tissue. The authors recognize it but consider it unnecessary in most cases where patients understand the beauty of a smaller breast.

As a limiting factor, this work does not compare the authors’ method with other techniques not yet described for these cases.

The scarcity of literature alerts us to the need for documentation and elaboration of studies comparing different tactics for this treatment that grows daily.

CONCLUSIONS

The authors conclude that using crossed flaps is a useful and safe alternative for breast reconstruction surgeries after definitive explantation using autologous tissues.

REFERENCES

1. Beekman WH, Hage JJ, Jorna LB, Mulder JW. Augmentation mammaplasty: the story before the silicone bag prosthesis. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;43(4):446-51.

2. Cronin TD, Gerow FJ. Augmentation mammaplasty: a new “natural fell” prosthesis. In: Transaction of the Third International Congress of Plastic Surgery (Excerpta Medica International Congress Serie Nº 66). Amsterdam; 1964.

3. Bozola AR, Bozola AC, Carrazzoni RM. Inclusão de Próteses Mamárias de Silicone - Poliuretano. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2006;21(1):18-22.

4. Charles-de-Sá L, Gontijo-Deamorim NF, Albelaez JP, Leal PR. Perfil da cirurgia de aumento de mama no Brasil. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34(2):174-86.

5. Miranda RE. O explante em bloco de prótese mamária de silicone na qualidade de vida e evolução dos sintomas da síndrome ASIA. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2020;35(4):427-31.

6. Magnusson MR, Cooter RD, Rakhorst H, McGuire PA, Adams WP Jr, Deva AK. Breast Implant Illness: A Way Forward. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:74S-81S.

7. Keane G, Chi D, Ha AY, Myckatyn TM. En Bloc Capsulectomy for Breast Implant Illness: A Social Media Phenomenon? Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41(4):448-59. DOI: 10.1093/asj/sjaa203

8. Tanna N, Calobrace MB, Clemens MW, Hammond DC, Nahabedian MY, Rohrich RJ, et al. Not All Breast Explants Are Equal: Contemporary Strategies in Breast Explantation Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(4):808-18.

9. Georgiade NG, Serafin D, Morris R, Georgiade G. Reduction mammaplasty utilizing an inferior pedicle nipple-areolar flap. Ann Plast Surg. 1979;3(3):211-8.

10. Bustos SS, Molinar V, Kuruoglu D, Cespedes-Gomez O, Sharaf BA, Martinez-Jorge J, et al. Inferior pedicle breast reduction and long nipple-to-inframammary fold distance: How long is safe? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74(3):495-503.

11. Maliniac JW. Arterial blood supply of the breast. Arch Surg. 1943;47:329-43.

12. Fischler R, Sperli A. Mastoplastia pela técnica dos retalhos cruzados: reavaliação de técnica. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2008;23(3):173-8.

13. Pitanguy I, Caldeira AML, Alexandrino A, Martinez JG. Mamaplastia redutora e mastopexia técnica Pitanguy. Vinte e cinco anos de experiência. Rev Bras Cir. 1984;74(5):33-46.

14. Pitanguy I. Mamaplastia Pitanguy. 1ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 1978.

15. Cammarota MC, Lima RQ, Almeida CM, Esteves BP, Curado DMDC, Ribeiro Júnior I, et al. Reconstrução de mama com expansor de Becker: uma análise de 116 casos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2016;31(1):12-8.

16. Ferreira MPS. Variação da técnica em “L” para redução de volume e correção das ptoses mamárias. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2008;23(4):248-53.

17. Hakme F, Gomes Filho BS, Muller PM, Sjostedt C. Técnica em “L” nas ptoses mamárias com confecção de retalhos cruzados. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 1983;73:87-91.

18. Miró AL. Tratamento das ptoses mamárias com retalhos cruzados sem prévia ressecção de pele. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2000;15(1):32-4.

19. Turner A, Abu-Ghname A, Davis MJ, Winocour SJ, Hanson SE, Chu CK. Fat Grafting in Breast Reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(1):17-23.

1. Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Serviço de Cirurgia Plástica, Brasília, DF, Brazil

OMC Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Statistical analysis, Final approval of the manuscript, Acquisition of funding, Data collection, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Project Management, Research, Methodology, Conducting operations and/or experiments, Writing - Original Preparation, Writing - Proofreading and Editing, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

TMAF Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Statistical analysis, Final approval of the manuscript, Acquisition of funding, Data collection, Conceptualization, Conception and study design, Resource Management, Project Management, Investigation, Methodology, Conducting operations and/or experiments, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Revision and Editing, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

JCD Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Statistical analysis, Final approval of the manuscript, Acquisition of funding, Data collection, Conceptualization, Conception and study design, Resource Management, Project Management, Investigation, Methodology, Conducting operations and/or experiments, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Revision and Editing, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

MSV Data Analysis and/or Interpretation, Statistical Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Data Gathering, Resource Management, Project Management, Writing - Manuscript Preparation, Visualization.

DBP Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Final approval of the manuscript, Data collection, Conception and design of the study, Project Management, Methodology, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Review and Editing, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

Corresponding author: Tristão Maurício de Aquino Filho SQS 105, Bloco G, apto 402, Asa Sul, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Zip code: 70344-070, E-mail: dr.tristaomauricio@gmail.com

Article received: September 15, 2021.

Article accepted: July 11, 2022.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter