Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

The role of plastic surgery in the treatment of pressure injuries: report of 38 cases in a trauma care center

Atuação da cirurgia plástica no tratamento de lesões por pressão: relato de 38 casos em centro de atendimento ao trauma

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Pressure injuries are caused by a local increase in external pressure, leading to ischemia and necrosis. They involve multidisciplinary treatment, and their management includes conservative and/or surgical procedures. The plastic surgeon plays a key role in the surgical treatment of these injuries.

Methods: Medical records of 38 patients with pressure injuries, single or multiple, treated by Plastic Surgery at Hospital do Trabalhador, Curitiba-PR, Brazil) from June 2012 to March 2020 were analyzed. In this observational study, the characteristics of 45 pressure injuries were considered together with the surgical techniques employed and their outcomes.

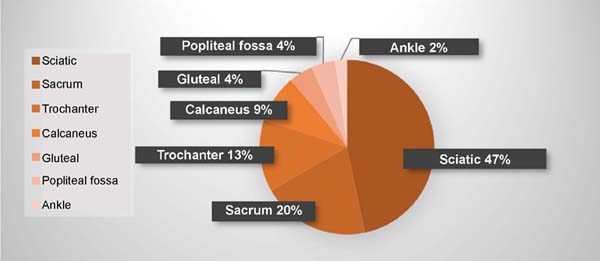

Results: The average age of the patients were 35.4 years, the majority being men. The lesions were located mainly in the ischiatic and sacral regions, predominating the classification of the III and IV degrees. The lesions were mostly located in the ischial, sacral and trochanteric regions, predominantly grades III and IV. Debridement was performed, followed by coverage with flaps and skin grafts, mostly gluteal VY advancement flaps and gluteal island. Some patients developed complications in the postoperative period, mainly flap dehiscence and/or infection.

Conclusion: Pressure injuries predominated in young adult male patients, unlike the global prevalence (elderly and/or patients with chronic diseases). The greatest incidences occurred in the ischial and sacral regions, explained by the limitation of movements charged to the profile of victims of major trauma. The most used flap was the gluteus maximus flap to treat these lesions.

Keywords: Pressure ulcer; Surgery, plastic; Surgical Flaps; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Trauma centers.

RESUMO

Introdução: Lesões por pressão são ocasionadas por aumento local da pressão externa, cursando com isquemia e necrose. Envolvem tratamento multidisciplinar e seu manejo engloba procedimentos conservadores e/ou cirúrgicos. O cirurgião plástico tem atuação primordial no tratamento cirúrgico destas lesões.

Métodos: Análise de prontuários de 38 pacientes com lesões por pressão, únicas ou múltiplas, tratados pela Cirurgia Plástica no Hospital do Trabalhador, Curitiba-PR, entre junho de 2012 e março de 2020. Nesse estudo observacional, foram consideradas as características de 45 lesões por pressão juntamente com a técnica cirúrgica empregada e evolução.

Resultados: A idade média dos pacientes foi de 35,4 anos, sendo a maioria homens. As lesões localizavam-se majoritariamente nas regiões isquiática, sacral e trocantérica, predominando os graus III e I V. Realizou-se debridamento, seguido por cobertura com retalhos e enxertos de pele, em maioria retalhos de avanço VY e em ilha de glúteo máximo. Alguns pacientes desenvolveram complicações no pós-operatório, principalmente deiscências de retalho e/ou infecção.

Conclusão: As lesões por pressão predominaram em pacientes homens adultos jovens, diferentemente da prevalência global (idosos e/ou portadores de doenças crônicas). As maiores incidências ocorreram nas regiões isquiática e sacral, explicadas pela limitação de movimentos incumbida ao perfil de vítimas de grandes traumas. Para tratamento desta lesões, o retalho mais utilizado foi o de glúteo máximo.

Palavras-chave: Úlcera por pressão; Cirurgia plástica; Retalhos cirúrgicos; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Centros de traumatologia

INTRODUCTION

Pressure injuries (PI) are defined by the National Pressure Sore Advisory Panel (NPUAP) as tissue damage to the skin and/or adjacent soft tissues induced by increased external pressure and usually appear at sites of bony prominences. Thus, they result from prolonged exposure without pressure relief on the tissues, generating tissue ischemia and necrosis. PIs are a significant problem for health services, as they often require prolonged treatments, with high costs and the involvement of multidisciplinary teams that require specific training1, 2, 3, 4.

PIs have a high prevalence in hospitalized and institutionalized patients who have an acute injury that leads to prolonged immobilization or in patients with exacerbation of disabling chronic diseases. In general, they are more common in the elderly, men, patients with sensory alterations, and immobilized and malnourished patients5. It is estimated that the incidence of pressure injuries in trauma victims varies from 0.4% to 30.6% for patients requiring hospitalization for more than 48 hours6, 7, 8, 9.

The diagnosis is clinical and made through physical examination. The PIs are then classified in order to define the therapeutic strategy. One of the most used classifications worldwide is the NPUAP, which classifies PIs in four stages according to the severity of the wound:

Stage I - Intact skin, but with persistent and non-blanching erythema even after pressure relief;

Stage II - Partial skin lesion, affecting the epidermis and dermis, with blisters;

Stage III - Deep lesion, reaching all layers of skin and subcutaneous tissue, but still not showing tendon, bone or muscle exposure;

Stage IV - Total tissue injury, with slough and exposure of structures such as tendon, joint, bone or muscle, necrotic tissue and the presence of infection1, 2.

The treatment of PI is complex. Conservative management includes measures that promote pressure relief at the wound site, nutritional optimization and dressings. Topical agents can be used (enzymatic, antimicrobial, growth factors, etc.), semi-occlusive coatings and negative pressure dressings, among others. Conservative management is indicated in PI grades I and II and preparation for surgical treatment5. Surgical treatment is mostly indicated in grade III and IV PI cases, which did not respond to conservative treatment. This treatment modality has as its fundamental principle the debridement of the wound, with the removal of necrotic and devitalized tissues, which may include partial bone removal. Wound closure depends on the location, size and extent of the PI. It encompasses several methods, such as primary closure, grafts and flaps. Recurrence or occurrence of a new lesion is not infrequent5, 10.

OBJECTIVE

To describe the epidemiology of pressure injuries surgically treated by the Plastic Surgery team of the Hospital do Trabalhador, analyzing the characteristics of patients and injuries, the surgical technique used and the evolution of the cases.

METHODS

From June 2012 to March 2020 (94 months), a retrospective observational study was carried out through the analysis of medical records of patients diagnosed with pressure injuries and submitted to surgical treatment by the Plastic Surgery team, in a trauma referral center - Hospital do Trabalhador, in Curitiba - PR. The project was analyzed and accepted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital do Trabalhador (CAAE: 38454520.4.0000.5225).

The following data were collected and analyzed: sex, age, presence of spinal cord injury and plegia, smoking, location and degree of injury classification, surgical procedures performed, recurrences and postoperative complications. The initial sample of the study was 42 patients, four patients were excluded from the analysis because they had incomplete medical records or developed other skin wounds that were not classified as pressure injuries, leaving 38 patients in the research sample.

For assessing risk factors in the development of PI, age and occurrence of spinal cord injury were considered predominant. The PIs were evaluated in terms of location, which could be in the sacrum, ischium, trochanter, calcaneus, ankle, popliteal fossa and gluteus. All patients underwent the most appropriate surgical correction for each case - exclusive debridement, primary closure, fasciocutaneous or myocutaneous flaps or skin grafts.

Regarding postoperative complications, the occurrence of surgical site infection, osteomyelitis, hematoma and suture dehiscence were evaluated.

RESULTS

Thirty-eight patients met the inclusion criteria, 32 males and six females, aged between 6 and 75 years (mean age 35.4 years). In 33 cases (86.84%), the patient had a single lesion, while another five patients (13.15%) had multiple PIs. In all, 45 pressure injuries were surgically treated.

Concerning risk factors, 22 patients had spinal cord injury (57.8%) resulting from spinal trauma or transverse myelitis sequelae, 17 of whom were paraplegic (44.7%), and five were quadriplegic (13.1%). The mean time of evolution of the pressure injury since the trauma was 6.2 months.

As for smoking, seven patients (18.4%) were smokers. However, it was not possible to establish a statistically significant relationship between smoking and postoperative complications.

The proposed surgical treatment was based on the classification of the lesion, the site of involvement, the patient’s general condition, conditions of care and support in the postoperative period, and the availability of a tissue donor area. The size of the defects varied between 2 and 30 centimeters in the largest diameter (average of 5.8 cm), being classified mostly in grades III and IV of the NPUAP (97.7%).

Among the affected regions, the ischial had the highest occurrence (46.6%), followed by lesions located in the sacrum and trochanter. In smaller numbers, PI in the calcaneus, popliteal fossa, gluteus and ankle were treated (Figure 1).

All cases underwent debridement of devitalized tissues. In only one case, wound debridement was performed exclusively. In 44 cases, the lesions were treated with tissue coverage. Because some injuries were confluent and close together, some cases of multiple injuries were treated with the same coverage.

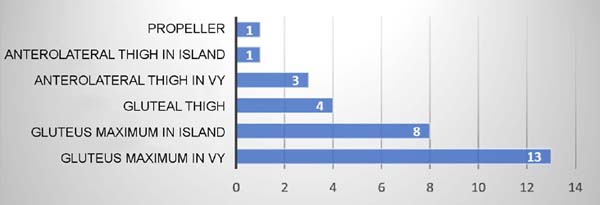

Considering the surgical techniques used for tissue coverage, 39 procedures were performed: in three cases, primary wound closure was possible (7.7%), in six cases, skin grafts were performed (15.4%), and in 30 cases, flaps (76.9%).

Regarding the skin grafts, three were full-thickness, taken from the inguinal region, and three were partial-thickness, taken from the lower third of the leg.

Among the types of flap, the gluteus maximus VY advancement fasciocutaneous flap was the most used (Figures 2 and 3), followed by the gluteus maximus island myocutaneous flap (Figures 4 and 5). The anterolateral fasciocutaneous flap of the thigh was used mainly in defects in the trochanteric region (Figures 6 and 7).

Among the 45 lesions treated in total, 44.4% had postoperative complications, namely: flap suture dehiscence (20%), surgical site infection (11.1%), osteomyelitis (8.8%), hematoma (2.2%) and flap necrosis (2.2%).

There was a need for reoperation in ten cases, including resuture of the flap in eight cases and making a new flap in two cases.

It was not possible to establish the mean follow-up time of patients at the end of the study due to the high rate of absences from scheduled outpatient consultations.

DISCUSSION

Pressure injuries currently represent one of the main complications in debilitated and chronically hospitalized and/or bedridden patients, especially the elderly or those with neurological disorders resulting from trauma. Most of these are preventable injuries and, in addition to prolonging hospital stays and increasing the risk of developing other complications, they contribute to greater physical and emotional suffering for these patients. Therefore, frequent and rigorous clinical evaluations are essential, paying special attention to changes in the skin color and appearance that is not intact, in addition to periodic changes in the decubitus position in patients at risk11.

The prevalence of pressure injuries was higher in young men, with a mean age of 35.4 years and an incidence of 84.2% in males. All patients were victims of accidents causing spinal cord injury or major fractures, with consequent limitation of movement and ambulation, predisposing to the emergence of PI.

In general, the global prevalence of PI is higher in elderly patients, with a significant increase in risk in patients over 75 years of age, as evidenced by Fogerty et al.12. This is due to the comorbidities associated with PI, which are more frequent in the elderly population. Regarding gender, the literature has not shown a significant difference in the prevalence of PI between men and women3, 11, 13.

However, the trauma victim population is composed of younger and male patients. Young men have a higher prevalence of spinal cord injuries, an important risk factor for PI in patients without other comorbidities, as demonstrated in the study by Ham et al. 8. In addition, medical devices are also associated with the emergence of pressure injuries in trauma patients8, 9. This explains the demographic data present in this study.

Considering the possibilities of treatment, the role of the plastic surgeon was essential in cases refractory to conservative treatment or deeper lesions, justifying the indication of surgical treatment mainly for the management of PI grades III and I V. Likewise, the choice of reconstruction procedure was based on individual factors of each patient, including the level of spinal cord injury and its repercussion on the body (plegias, bed restriction or need to use a wheelchair), location, extent and severity of the injury, history of injuries or previous surgeries, habits and daily care, nutritional status and previous comorbidities.

Surgical debridement was performed in 100% of the cases. Debridement is always the initial step in the surgical treatment of pressure injuries, as removing devitalized tissue is essential for tissue healing5, 14.

We opted for exclusive debridement in only one patient because it was the only case treated surgically classified in grade II of the NPUAP classification, with a small diameter and good healing conditions by secondary intention.

Studies indicate that 95% of patients with spinal cord injuries will present PI throughout their lives15. The correlation between pressure injuries and spinal cord injuries was 57.8% in this study, with 44.7% of the patients having paraplegia and 13.1% quadriplegic. Sciatic injuries arise in patients who remain sitting for long periods5, a fact that explains this high incidence observed. In general, injuries in this location are treated with myocutaneous or purely muscular flaps, the most used being the gluteus maximus, gracilis, medial thigh and posterior thigh. Fasciocutaneous flaps are less used due to the need for greater thickness for satisfactory wound coverage5. Gluteus maximus flaps were the choice for 76% of ischial PI coverage.

Pressure injuries in the distal regions of the lower limbs had an incidence of 15.6% in this study. This is justified by the fact that the hospital where the study was conducted is a state reference for trauma, with a high number of car accidents and falls, causing complex fractures, use of medical devices and long immobilization time of lower limbs.

In 57.1% of the cases, closure was possible only with a skin graft, due to the earlier approach and less local tissue loss, without bone exposure. Grafts tend to have limited use in the treatment of PI, due to their thin thickness and low resistance in areas of friction, with recurrence rates close to 70%, which is contraindicated in areas of bony prominences5.

In the two cases of lesions in the popliteal fossa, a reverse anterolateral thigh flap was chosen in one case and total skin graft in the other. The flap evolved with hematoma, infection and dehiscence, culminating in total necrosis of the flap and the need for a new surgical correction. The two PIs in the gluteal region were closed primarily as they were not very extensive and had adjacent tissue available, preserving a possible skin donor area.

The coverage of PIs is mostly performed with the manufacture of flaps. Fasciocutaneous flaps are an excellent option, as they are well vascularized, provide good coverage of bony prominences and cause little damage to the donor area5, 16, 17. On the other hand, myocutaneous flaps also have good vascularization and excellent coverage, indicated in deeper wounds and needing thicker coverage. They have the disadvantage of generating more damage in the donor area5.

The gluteus maximus fasciocutaneous flap in VY advancement was the most used, representing 33.3% of the procedures. Calil et al.10 justify the wide use of this flap in the treatment of PI due to the easy mobilization of the tissue when performed unilaterally, allowing good reach and satisfactorily covering the lesion area. In lesions in the sacral region, this flap is safe and allows further advancement if necessary, justifying the majority use of the gluteus maximus flap in VY for the treatment of sacral PI5.

Trochanteric lesions occur more frequently in patients who remain in lateral recumbency for prolonged periods. For the treatment of pressure injuries in this region, the anterolateral thigh and gluteus maximus flaps were the most used. The fascia lata myocutaneous flap is the method of choice for coverage of trochanteric PI 5, 18, 19, but studies show a recurrence rate of 80% using this technique, especially in patients with spinal cord injuries19. In patients with the ability to walk, this flap is associated with the risk of destabilization of the quadriceps femoris muscle and functional deficit. Anterolateral thigh and gluteus maximus flaps have been described as good options for correcting trochanteric PI, preserving local muscles without important functional sequelae19.

In 47.5% of the treated cases, there were postoperative complications. Of this total, 72.7% were PI in the sacral and/or ischial regions. The high incidence of complications in these regions is related to the difficult healing control due to the need for an environment with minimal pressure on the lesion and other mechanisms of tissue stress, a fact that is complex, as most patients are bedridden and/or bedridden. or spinal cord injuries2. Furthermore, these are lesions whose surgical scars are susceptible to contamination, as they are close to areas of contact with urine and feces20, generating moisture, contamination and infection that are difficult to control.

PI recurrence rates range from 3% to 82%, averaging around 70%. Complication rates are around 36%5, 21, 22. In our study, the complication rate was 44.4%, with suture dehiscence predominating (20%), requiring resuture or a new correction in 22.2% of these cases. In our study, the recurrence rate was 7.9%. This fact can be explained by the large number of injuries reported in different locations in the lower limbs, as these have a lower recurrence rate23, 24.

CONCLUSION

Most of the population affected by pressure injuries treated surgically by the Plastic Surgery team in public service in Curitiba developed only one injury. Young male patients predominated, with a mean age of 35.4 years, and 57.8% had spinal cord injury. Considering the classification used, 97.7% of the injuries were classified in severe stages, with the highest incidence in the ischial region. Considering the treatment choice, 100% of cases underwent debridement, and only patients without clinical conditions did not receive surgical tissue coverage, mostly fasciocutaneous flaps, with a complication rate of 44.4%.

REFERENCES

1. Pressure ulcers prevalence, cost and risk assessment: consensus development conference statement--The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Decubitus. 1989;2(2):24-8.

2. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel; Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance; Haesler E, ed. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/ Injuries: Clinical Practice Guide. EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA; 2019.

3. Santos LLR, Ferreira LM, Sabino Neto MS. Úlcera por pressão. In: Ferreira LM, ed. Manual de Cirurgia Plástica. São Paulo; 1995. p. 214-7.

4. Ferreira LM, Calil JA. Etiopatogenia e tratamento das úlceras por pressão. Diagn Trat. 2001;(6):36-40.

5. Cushing CA, Phillips LG. Evidence-based medicine: pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(6):1720-32. PMID: 24281597 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a808ba

6. Watts D, Abrahams E, MacMillan C, Sanat J, Silver R, VanGorder S, et al. Insult after injury: pressure ulcers in trauma patients. Orthop Nurs. 17(4):84-91. PMID: 9814340 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006416-199807000-00012

7. O’Sullivan KL, Engrav LH, Maier R V, Pilcher SL, Isik F F, Copass MK. Pressure sores in the acute trauma patient: incidence and causes. J Trauma. 1997;42(2):276-8. PMID: 9042881 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199702000-00016

8. Ham HW, Schoonhoven LL, Galer AA, Shortridge-Baggett LL. Cervical collar-related pressure ulcers in trauma patients in intensive care unit. J Trauma Nurs. 2014;21(3):94-102. PMID: 24828769 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/JTN.0000000000000046

9. Grigorian A, Sugimoto M, Joe V, Schubl S, Lekawa M, Dolich M, et al. Pressure Ulcer in Trauma Patients: A Higher Spinal Cord Injury Level Leads to Higher Risk. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2018;9(1-3):24-31.e1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccw.2018.06.001

10. Calil JA, Ferreira LM, Sabino Neto S, Castilho HT, Garcia EB. Aplicação clínica do retalho fáscio-cutâneo da região posterior da coxa em V-Y. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2001;47(4):311-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302001000400033

11. Blanes L, Duarte I da S, Calil JA, Ferreira LM. Avaliação clínica e epidemiológica das úlceras por pressão em pacientes internados no Hospital São Paulo. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2004;50(2):182-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302004000200036

12. Fogerty MD, Abumrad NN, Nanney L, Arbogast PG, Poulose B, Barbul A. Risk factors for pressure ulcers in acute care hospitals. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(1):11-8. PMID: 18211574 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00327.x

13. Bryant RA, Shannon ML, Pieper B, Braden BJ, Morris DJ. Pressure ulcers. In: Bryant RA, ed. Acute and chronic wounds: nursing management. St Louis: Mosby; 1992. p. 105-63.

14. Ford CN, Reinhard ER, Yeh D, Syrek D, De Las Morenas A, Bergman SB, et al. Interim analysis of a prospective, randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus the healthpoint system in the management of pressure ulcers. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49(1):55-61: discussion 61. PMID: 12142596 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000637-200207000-00009

15. Houghton PE, Campbell KE, CPG Panel. Canadian Best Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers in People with Spinal Cord Injury. A resource handbook for Clinicians [Internet]. 2013. p. 1-317. Disponível em: https://onf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Pressure_Ulcers_Best_Practice_Guideline_Final_web4.pdf

16. Lee SS, Huang SH, Chen MC, Chang K P, Lai CS, Lin SD. Management of recurrent ischial pressure sore with gracilis muscle flap and V-Y profunda femoris artery perforator-based flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2009;62(10):1339-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2007.12.092

17. Wettstein R, Tremp M, Baumberger M, Schaefer DJ, Kalbermatten DF. Local flap therapy for the treatment of pressure sore wounds. Int Wound J. 2015;12(5):572-6. PMID: 24131657 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12166

18. Milcheski DA, Mendes RRS, Freitas FR, Zaninetti G, Moneiro Júnior AA, Gemperli R. Brief hospitalization protocol for pressure ulcer surgical treatment: outpatient care and one-stage reconstruction. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2017;44(6):574-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-69912017006005

19. Ishida LH, Munhoz AM, Montag E, Alves HR, Saito FL, Nakamoto HA, et al. Tensor fasciae latae perforator flap: minimizing donor-site morbidity in the treatment of trochanteric pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(5):1346-52. PMID: 16217478 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000182222.66591.06

20. Tang J, Li B, Gong J, Li W, Yang J. Challenges in the management of critical ill COVID-19 patients with pressure ulcer. Int Wound J. 2020;17(5):1523-4. PMID: 32383319 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13399

21. Keys KA, Daniali LN, Warner KJ, Mathes DW. Multivariate predictors of failure after flap coverage of pressure ulcers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(6):1725-34. PMID: 20517098 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d51227

22. Disa JJ, Carlton JM, Goldberg NH. Efficacy of operative cure in pressure sore patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89(2):272-8. PMID: 1732895 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199202000-00012

23. Relander M, Palmer B. Recurrence of surgically treated pressure sores. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;22(1):89-92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/02844318809097940

24. Kierney PC, Engrav LH, Isik F F, Esselman PC, Cardenas DD, Rand R P. Results of 268 pressure sores in 158 patients managed jointly by plastic surgery and rehabilitation medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(3):765-72. PMID: 9727442 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199809010-00022

1. Universidade Federal do Paraná, Hospital de Clínicas, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

2. Hospital do Trabalhador, Serviço de Cirurgia Plástica Reparadora, Curitiba, PR,

Brazil.

3. Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

4. Universidade Positivo, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

CP Writing - Preparation of the original, Proofing and Editing.

DRP Study conception and design, Project Management, Methodology.

VSO Writing - Proofreading and Editing.

APTK Statistical analysis, Data Collection.

EMS Statistical Analysis, Data Collection, Research.

GSSJ Final approval of the manuscript, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Project Management, Methodology, and Supervision.

Corresponding author: Carolina Peressutti Rua General Carneiro, 181, Alto da Glória, Curitiba, PR, Brazil Zip Code: 80060-900 E-mail: carol.peressutti@gmail.com

Article received: May 28, 2021.

Article accepted: October 15, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Institution: Hospital do Trabalhador, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter