Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Correlation between facial lipofilling and hyaluronic acid filling languages

Correlação entre a linguagem de lipoenxertia e de preenchimento facial com ácido hialurônico

ABSTRACT

Introduction: As has been demonstrated, volume loss is a primary cause of aging appearance. So, the demand for filling materials that are safe, long-lasting, and biocompatible has grown, increasing the emphasis on lipografting. However, some issues regarding standardization are still unclear, like areas to be injected and volumes. So, the main objective is to analyze the results of a case series and systematize the filler volumes to be used and correlate the language used in facial lipografting with that used in MD Codes®.

Methods: Review the medical records of those who underwent facial fat grafting. Selection of donor area was proceeded based on convenience criteria, which assesses the ease of positioning, the abundance of material, and the patient's body contour. Harvesting was by manual aspiration. Preparation was done by Colemans' technique. Application areas: To draw a parallel between the knowledge acquired with facial lipografting and the fillings using synthetic material, the nomenclature used in MD Codes® was used.

Results: 54 facial lipografting were included (11% men / 88.88% women). The average age is 43.94 years (20 to 71, standard deviation 11.21). Follow-up average time was 155.61 days (range 7-543, standard deviation 156.05). There were no complications related to the method. The mean volume injected was 29.83ml (range 6-53.9, standard deviation 12.07).

Conclusion: Autologous lipografting is a feasible procedure for certain cases of facial rejuvenation. The MD Codes® language can be used in parallel with the anatomical description of the injected regions in this study.

Keywords: Face; Hyaluronic acid; Dermal fillers; fat; Reconstructive surgical procedures.

RESUMO

Introdução: A perda de volume é a principal causa da aparência de envelhecimento. Assim, a demanda por materiais de preenchimento que sejam seguros, duradouros e biocompatíveis tem crescido, com ênfase na lipoenxertia. Porém, algumas questões relativas à padronização ainda não estão claras, como áreas a serem injetadas e volumes. Assim, busca-se analisar os resultados de uma série de casos e sistematizar os volumes de preenchimento a serem utilizados, bem como correlacionar a linguagem usada na lipoenxertia facial com a do MD Codes®.

Métodos: Revisão dos prontuários de pacientes que realizaram lipoenxertia facial. A seleção da área doadora foi procedida com base em critérios de conveniência, como facilidade de posicionamento, abundância de material e o contorno corporal do paciente. A colheita foi por aspiração manual. A preparação foi feita pela técnica de Coleman. Áreas de aplicação: para traçar um paralelo entre os conhecimentos adquiridos com a lipoenxertia facial e o preenchimento com material sintético, foi utilizada a nomenclatura utilizada nos MD Codes®.

Resultados: Foram incluídos 54 lipoenxertos faciais (11% homens / 88,88% mulheres). Idade média de 43,94 anos (20 a 71, desvio padrão 11,21). O tempo médio de acompanhamento foi 155,61 dias (variação de 7-543, desvio padrão 156,05). Não houve complicações relacionadas ao método. O volume médio injetado foi de 29,83ml (intervalo 6-53,9, desvio padrão 12,07).

Conclusão: A lipoenxertia autóloga é um procedimento factível para alguns casos de rejuvenescimento facial. A linguagem MD Codes® pode ser usada em paralelo com a descrição anatômica das regiões injetadas neste estudo.

Palavras-chave: Face; Ácido hialurônico; Preenchedores dérmicos; Gorduras; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos

INTRODUCTION

By superimposing photographs of patients in their youth and senility, Lambros observed no inferior displacement of the position of several reference points of the face, concluding that ptosis is not a preponderant factor of aging. Consequently, he postulated that volume loss is a primary factor in aging the upper midface region1.

Tonnard & Verpaele agreed with Lambros regarding the central portion of the face, while true ptosis occurs in the periphery. Thus, they combined the antigravity facelift procedures with volumization by fat grafting2.

In the wake of the perception that aging is linked to volume loss, the demand for filling materials that are safe, long-lasting and biocompatible has grown, increasing the emphasis on fat grafting3.

Although Gir et al.4 cite the lack of reliability and consistency in the final clinical result of fat grafts as major concerns, this seems to be being overcome since Kling et al.5 found that 80% of the 456 surgeons who responded to the survey of their study, used the method. Thus, fat has been the material of choice for facial fillers, in the opinion of many plastic surgeons, because it is abundant, cheap and easily available4.

However, the literature does not provide clear data on how much injected fat actually remains on the face, making it difficult to decide how much to inject6.

Shue et al.7 performed a review, focusing on the description of injected volumes. Correlating the injected volumes with the results obtained in several cases may be a solution to the difficulty caused by the fact that we do not know the percentage of graft loss. In other words, it would be more important to know how much it is necessary to inject each type of deformity than to quantify the volume retained.

In their review, Shue et al.7 show no consensus on how much to inject in each area. They also demonstrate that only 19 of the 81 articles eligible for their review cited volumes and applied areas, with n varying between 1 and 83 patients per article. They also stated that the amount of fat injected into each facial compartment is typically based more on the surgeon’s experience than scientific information. Accordingly, a recent article by us describes the application areas with their respective standardized volumes in 151 consecutive cases, also based on our clinical experience, without solid science behind it8.

In 2017, more than 85,000 facial fat fillers were performed in the United States, more than three times the number of otoplasties in the same period9. Even though it is considered a significant number for a surgical procedure, it is very small compared to the 2.7 million fillings with synthetic materials in the same year9.

On the other hand, although non-surgical procedures are more frequent, there are more articles on facial fat grafting. Therefore, it would be interesting to find a way to take advantage of the practical experience accumulated with these numerous non-surgical procedures in the exercise of fat grafting and take advantage of the effervescent scientific production of fat grafting to improve fillings with synthetic materials.

The present study deepens the systematization made in a previous publication, updates small changes in the volume distribution and initiates a semantic correlation with the methodology of facial fillings with synthetic materials.

The systematization follows the technique described by Coleman10, with the adaptations described by Lam et al. in the book Complementary Fat Grafting11. The injection receiving areas’ descriptions are represented with the same symbols used in the MD Codes®12 facial filling methodology.

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the results of the case series and systematize the volumes to be applied, correlating the language used in facial fat grafting with the language used in the Md Codes®12 methodology.

METHODS

This is a retrospective clinical trial based on a review of the medical records of all patients operated on in the Plastic Surgery Service of the Clínica Eduardo Furlani between 08/15/2017, when we started to correlate the descriptive language of facial fat grafting with the descriptive language of the methodology Md Codes®, and 02/25/2019, in Fortaleza-CE, Brazil. All patients undergoing facial fat grafting were included. The main author operated all. Patients undergoing fat grafting for the exclusive treatment of acne scars were not included. All determinations of the Helsinki agreement were followed, and all patients signed a free consent form after clarification. The Research Ethics Committee approved the study under opinion number: 3,922,266.

Description of the technique used

Fat collection

Donor area

The choice of removal area followed the criteria of convenience due to the ease of positioning, the abundance of material and the patient’s body contour. Thus, the most frequent locations were the flanks and trochanteric regions. Patients undergoing abdominoplasty had the region excised in the hypogastrium as the donor area of choice.

Withdrawal method

Patients undergoing regional blocks for simultaneous body procedures had the donor area infiltrated with a 0.9% NaCl solution and 1:200,000 adrenaline. In cases without an anesthetic block, the solution was added with 0.4% lidocaine and 0.01% levobupivacaine. The infiltrated volume corresponds approximately to the volume scheduled for withdrawal.

Fat removal was performed by aspiration with a 3mm cannula with 16 1mm holes, cutting edges (Fagha Medical), and a 10ml Luer lock syringe (BD Medical), with manually controlled plunger traction, seeking to maintain negative pressure generated by pulling the syringe 1cc.

The technique differs from Lam et al.11 by not using albumin solution and cannulas from another manufacturer.

Preparation

Filled syringes are decanted while others are withdrawn. As a rule, the former quickly decant a clear infranatant, which is discarded, and the syringe returns to be filled by the surgeon.

The syringes are closed and taken to the centrifuge (Cirúrgica Monserrat®, R=100mm), with a rotation of 2000rpm (448 G), for 4 minutes. Then the infranatant and supernatant are discarded. Gauze is placed in contact with the top of the fat to absorb the residual oil.

The remaining fat in the syringe is transferred to another syringe to complete the volume of 10ml. The fat is slightly homogenized, mixed between two syringes, using an adapter that connects the two syringes. It is then transferred again to 1ml syringes for application.

Preparation of the receiving area

Patients undergoing body procedures, rhytidoplasty and other simultaneous facial procedures are sedated, and those undergoing rhinoplasty receive general anesthesia. Cases of isolated fat grafting are performed only with local anesthesia.

In all cases, infraorbital, mental and zygomaticofacial branches of the trigeminal nerve are blocked. The recipient areas are infiltrated with 0.9% NaCl solution, 1:200.00 adrenaline, and 0.4% lidocaine with the same cannulas used to inject the fat. In cases of rhytidectomy, the solution has an adrenaline concentration of 1:400,000.

Fat infiltration

The cannulas have a lumen of 1.2 mm and a length of 3 to 7 cm (Rhosse Instruments®).

We only used straight cannulas coupled to 1ml syringes (BD Medical®).

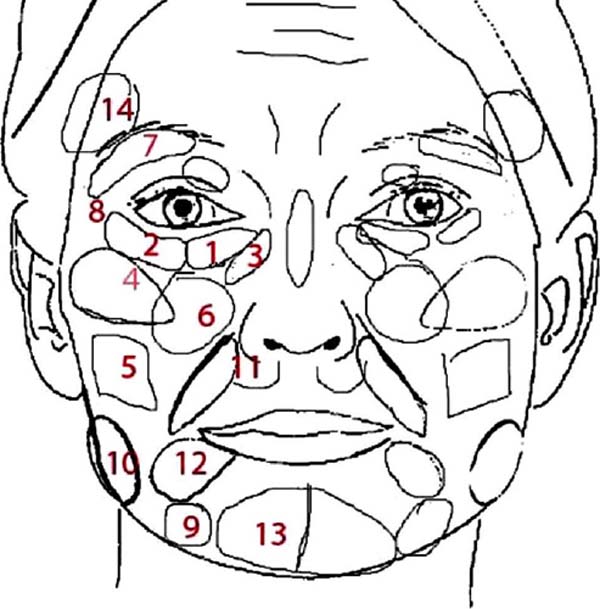

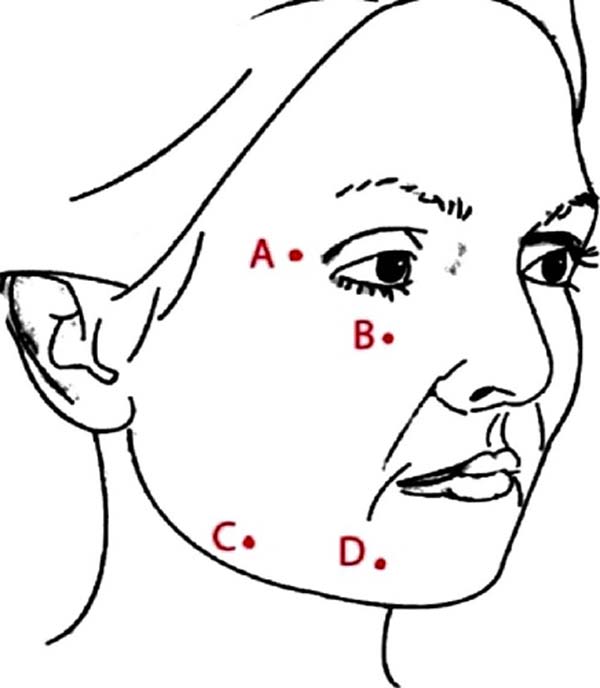

The cannula entry points are routinely punctured with a 25x7 cutting needle at locations A, B, C and D, as shown in Figure 1. Other perforations are performed as needed in each case. There is no need to close the incisions.

Application areas

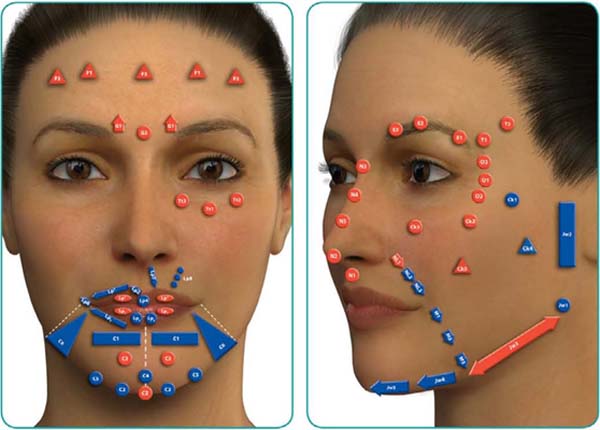

The preparation and application methodology followed that described by Lam et al.11. The injection is performed antegrade and retrograde, with the injection of approximately 0.1 ml for every 1 cm displacement of the cannula. The application areas are represented in Figure 2.

Description of application areas

In order to establish a parallel between the knowledge acquired with facial fat grafting and synthetic material fillings, the nomenclature that has been disseminated as Md Codes®12 was used.

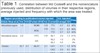

Table 1 presents the equivalence as understood by the authors. It also presents a correlation with the nomenclature previously used and with the findings of the review by Shue et al.7,8.

| Region according to publication/volume injected | Vol. Injected | Freq | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article Shue et al.7 | Vol. | V/AS | Furlani 2018 | Vol. | Current | Average | SD | |

| Infraorbital region | 1.4 | MOIM | 1.03 | TT3 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 46% | |

| MOIL | 1.03 |

TT1 TT2 |

0.7 0.7 |

0.2 0.2 |

46% 44% |

|||

| Nasolabial sulcus | 2.8 | FPC | 1.67 | NL1 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 61% | |

| S/E |

NL2 NL3 |

1.0 0.0 |

- - |

2% 0% |

||||

| Cheeks | 25.7 | 4.7 | MLAT | 2.1 | CK1 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 87% |

| CK2 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 76% | |||||

| CK4 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 28% | |||||

| 3.5 | BUCAL | 2.3 | CK5 | 2.0 | - | 2% | ||

| 2.6 | MANT | 3.1 | CK3 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 20% | ||

| FNJ | 1 | |||||||

| Eyebrow | 5.5 | MOS | 1.1 | E1 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 11% | |

| E2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 11% | |||||

| E3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 6% | |||||

| No equivalent | APL | 0.6 | O1 | 0.0 | - | 0% | ||

| O2 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 4% | |||||

| O3 | 0.5 | - | 2% | |||||

| Mento | 6.7 | MENT | 5.8 | C1 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 50% | |

| C2 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 69% | |||||

| C3 | 0.0 | - | 0% | |||||

| C4 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 56% | |||||

| C5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 4% | |||||

| JW5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 4% | |||||

| Mandibular Area | 11.5 | MANDL | 4.8 | JW1 | 5.4 | 1.0 | 22% | |

| MANDR | JW2 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 4% | ||||

| MANDC | JW3 | 0.0 | - | 0% | ||||

| SPB | 2.3 | JW4 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 39% | |||

| C6 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 6% | |||||

| Marionette Lines | 1.3 | MNT | 0.6 | M1 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 6% | |

| M2 | 1.0 | - | 2% | |||||

| Temporal | 5.9 | TEMP | 2.9 | T1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 15% | |

| No equivalent | LIPS | LP6 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 22% | |||

| Upper lip | 3 | LP1S | 3.7 | 1.8 | 41% | |||

| Lower lip | 3.7 | LP1I | 6.1 | 2.8 | 41% | |||

| Frontal | 6.5 | FRONTAL | F1 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 9% | ||

| F2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 9% | |||||

| F3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 6% | |||||

| Glabella | 1.4 | GLABELA | G1 | 0.0 | - | 0% | ||

| G2 | 1.0 | - | 2% | |||||

| No equivalent | DORSO N | NOSE | 2.6 | 1.3 | 13% | |||

Legend of applied areas - MOIM: medial inferior orbital margin, MOIL: lateral inferior orbital margin, FPC: precanine fossa, MLAT: lateral mandible, BUCAL, MANT: anterior malar; FNJ: nasojugal fossa, MOS: superior orbital margin, APL: lateral eyelid angle, MENT: chin, MANDL: lateral mandible (mandible angle); MANDR: ramus of the mandible; MANDC: body of the mandible; SPB: mandibular pre-pouch sulcus; MNT: puppet, TEMP: temporal, LIPS: lips; FRONT: frontal region; GLABELA: glabella; DORSO N: dorsum of the nose.

TT3: infraorbital medial tear trough, TT1: infraorbital central tear trough, TT2: infraorbital lateral tear trough, NL1: Upper nasolabial fold, NL2: Central nasolabial fold, NL3: Lower nasolabial fold, CK1: Zygomatic arch, CK2: Zygomatic eminence, CK4: Lateral lower cheek/parotid area, CK5: Submalar/buccal area, CK3: Anteromedial cheek, E1: Eyebrow tail, E2: Eyebrow center, E3: Eyebrow head, O1: Central lateral orbital, O2: Lower lateral orbital, O3: Upper orbital lateral, C1: Labiomental angle, C2: Chin apex, C3: Anterior chin, C4: Anterior chin/soft tissue pogonion, C5: Lateral lower chin, JW5: Lower anterior chin, JW1: Mandible angle, JW2: Preauricular area, JW3: Mandible body, JW4: Lower prejowl, C6: Lateral chin, M1: Upper marionette line, M2: Central marionette line, T1: Anterior temple, LP6: Oral commissure, LP1S: Upper lip, LP1I: Lower lip, F1: Medial forehead, F2: Lateral forehead, F3: Central forehead, G1: Lateral glabella, G2: Central glabella.

RESULTS

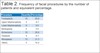

Sixty facial fat grafting procedures were performed between 08/15/2017 and 02/25/2019. Six cases were excluded due to data loss. Men represented 11.11% (six cases) and women 88.88% (48 cases) of the total. Age ranged between 20 and 71 years (mean 43.94 years, standard deviation – SD – 11.21 years). Twenty-nine patients (53.70%) had some associated body surgery, and 32 patients (59.3%) had some associated facial surgery, whose frequencies are shown in Table 2.

| Procedure | Quantity | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Frontoplasty | 10 | 20.8 |

| Upper blepharoplasty | 4 | 8.3 |

| Lower blepharoplasty | 0 | 0.0 |

| Mentoplasty | 0 | 0.0 |

| Bichectomy | 10 | 20.8 |

| Otoplasty | 4 | 8.3 |

| Rhinoplasty | 15 | 31.3 |

| Others | 5 | 10.4 |

The mean follow-up time was 155.61 days (minimum 7, maximum 543, SD 156.05).

One patient (2%) underwent a second fat grafting procedure, with an interval of 16 months between interventions.

There were no complications related to the method, considering that the presence of ecchymosis and edema in the first 15 days are no complications but normal consequences of the procedure. We did not observe the appearance of previously non-existent asymmetries.

We could not retrieve accurate information on injected volumes in six of the 60 cases (10%). Thus, the injected volume statistics were calculated considering 54 patients. Table 1 shows the distribution of volumes, in their respective regions, with the average injected and the frequency with which this area was treated. The average volume injected was 29.83 ml, ranging from 6 to 53.9 (SD 12.07).

DISCUSSION

Even with the increase in fat grafting, there are few high-quality clinical studies for any of the technical steps involved, such as selection of the donor area, fat collection, processing and injection technique13. In addition, studies do not usually show the volumes injected specifically in each area.

In a previous article, with 151 consecutive cases, we published a standardization of volumes used in each area, without major variations from case to case, as if it were a therapeutic dose for each region. Thus, planning was based more on the choice of areas to correct than on the volume to be injected into each area. This strategy seemed successful, as it facilitated planning and allowed us to have consistency in the results8.

In this article, we made minor modifications to the injected volume pattern, but we kept the concept of the therapeutic dose for each area or, at least, the minimum dose to have results in each area.

A recent systematic review raised the articles that described the volumes injected by the facial subunit, with which we compared our volumes7.

In the present series, we intend to bring the language used in publications on fat grafting closer to the language used in facial filling with synthetic materials to make the information on the two types of procedures interchangeable. Thus, Figure 2 demonstrates the applied areas, with the nomenclature used by the Md Codes®12 methodology and reproduced in this study, while Figure 3 demonstrates the nomenclature used by us in the previous series.

Table 1 was created to analyze the equivalence of nomenclatures and injection volumes performed by the authors of the review by Shue et al.7, by our group in a previous series and by our group in the present study.

What changed from the previous series to this one?

Anterior Malar (Anterior Malar + FNJ) reduced from 4.1 to 2 (CK3). This way, it approached the literature with an average of 2.6 ml. Lateral malar increased from 2.1ml to 5.1ml (ck1 3.1ml, ck2 2.0ml), getting closer to the literature (4.7ml, on average)7.

We started to inject in the lip and nasal dorsum.

Nasolabial sulcus increased from 1.7ml to 2.9ml, getting closer to the literature average (average of 2.8ml)7.

The mean volume applied to the chin was 5.8 ml in the previous series, similar to the average in the literature (6.7 ml), while we found 13.8 ml in this series. Although the volume seems to have doubled concerning the literature average, when analyzing each article in the review by Shue et al.7, we observed that only two groups described volumes injected into the chin: Xie et al.14, with an average of 2ml, and Coleman & Katzel, with an average of 16ml15.

Although Xie et al.14 reported an average of 2ml, they themselves do not seem to be satisfied with this volume, as they state that there is a higher rate of resorption in this area, which may require other procedures. Coleman reports, in three articles, the volume of 12, 16 and 20 ml, respectively. Such volume is closer and even superior to that practiced in our series. We cannot say there is a higher absorption rate in this area, as suggested by Xie et al., but it seems that the reported volume of 2ml is insufficient to modify the chin10,14,15,16.

Terminology problem

When examining the review by Shue et al.7, we noticed a huge effort to discover the volumes injected in each area and compare with other authors, as each used different terminology. For example, Mailey et al.17 use the term “supramental crease,” probably referring to the term “mental lip sulcus,” which we use in this terminology (represented by the C1 code). However, no other article used the same term.

Coleman & Katzel15 use the term “mental Groove,” whereas Pessa & Rohrich18 and Boneti et al.19 use the term “mental crease.” None of these explain what they refer to, but they are believed to refer to a depression in the anterior mid-chin region between the mental fat compartments.

Some articles use the term “chin,” equivalent to mento, which we used in our previous series8,10,14,15. However, we consider the term very general, and we started subdividing it into several sub-areas since it is not only intended to increase but to achieve certain forms. For example, when filling the region of the mental lip sulcus, there seems to be an inferior rotation of the mento, while there seems to be superior rotation with the filling of what we call C4 (middle anterior portion of the mento). Thus, it is necessary to specify the injected area.

We consider “bochecha” or “cheek” in English one of the vaguest and most confusing terms. Pessa & Rohrich18 define the “Anatomic region with precise boundaries: the superior boundary is the lower eyelid, the lateral boundary the periauricular region, inferior boundary the neck, and the medial boundary is formed by the nose, lips, and chin. These boundary zones occur at both a superficial and deep level”.

Even so, authors such as Wang et al.20 use the term “cheek” in their income statement and state that they injected, on average, 29.3 ml in each cheek without further specification. The description “cheek” is insufficient for those who practice facial fat grafting because it is necessary to know exactly how much and where to inject.

The authors cited use the much more specific concept of facial fat compartments when describing the application technique, as demonstrated in the description of their injection sequence: “(1) medial part of the deep medial cheek fat compartment; (2) medial part of the sub- orbicularis oculi fat compartment; (3) lateral part of the deep medial cheek fat compartment; (4) lateral part of the nasal base; (5) upper lip in the submucosa layer; and (6) superior part of the buccal fat pad “20. We did not find other authors who used the concepts of facial fat compartments in the practice of lipoinjection.

Some descriptions are based on surface anatomy, others on bone structure. Some descriptions are based on clinical practice, others on anatomical concepts and subdivisions. Some authors use technical terms, while others incorporate popular denominations, such as “Marionette lines.” The fact is that the level of development of anatomical terms is not yet capable of portraying the reality of those who work in this area, leading to difficulties in exchanging knowledge.

This lack of unity of language proved to be a bigger obstacle than we imagined in understanding patterns. We believe, therefore, that efforts in language development can be a preponderant factor in the exchange of ideas. At this moment, it is perhaps more important to discuss semantic issues than centrifugation techniques, collection areas, preparation methods, etc.

CONCLUSION

Autologous fat grafting was applied to 60 consecutive patients without complications related to the method, being a feasible procedure for certain cases of facial rejuvenation.

The MD Codes® language can be used in parallel with the anatomical description of the injected regions.

REFERENCES

1. Lambros V. Observations on periorbital and midface aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(5):1367-76.

2. Tonnard P, Verpaele A, Bensimon R. Centrofacial Rejuvenation: New York: Thieme Publishers; 2017.

3. Broder KW, Cohen SR. An overview of permanent and semipermanent fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 Suppl):7S-14S.

4. Gir P, Brown SA, Oni G, Kashefi N, Mojallal A, Rohrich RJ. Fat grafting: evidence-based review on autologous fat harvesting, processing, reinjection, and storage. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(1):249-58.

5. Kling RE, Mehrara BJ, Pusic AL, Young VL, Hume KM, Crotty CA, et al. Trends in autologous fat grafting to the breast: a national survey of the american society of plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(1):35-46.

6. Fontdevila J, Serra-Renom JM, Raigosa M, Berenguer J, Guisantes E, Prades E, et al. Assessing the long-term viability of facial fat grafts: an objective measure using computed tomography. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28(4):380-6.

7. Shue S, Kurlander DE, Guyuron B. Fat Injection: A Systematic Review of Injection Volumes by Facial Subunit. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(5):1261-70.

8. Furlani EAT, Saboia DB. Rejuvenescimento facial com lipoenxertia: sistematização e estudo de 151 casos consecutivos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2018;33(4):439-45.

9. American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). 2017 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. Arlington Heights: ASPS; 2017. Disponível em: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2017/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2017.pdf

10. Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting: more than a permanent filler. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 Suppl):108S-20S.

11. Lam SM, Glasgold MJ, Glasgold RA. Complementary fat grafting. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

12. de Maio M. MD Codes™: A Methodological Approach to Facial Aesthetic Treatment with Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2021;45(2):690-709.

13. Geissler PJ, Davis K, Roostaeian J, Unger J, Huang J, Rohrich RJ. Improving fat transfer viability: the role of aging, body mass index, and harvest site. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(2):227-32.

14. Xie Y, Zheng DN, Li Q F, Gu B, Liu K, Shen GX, et al. An integrated fat grafting technique for cosmetic facial contouring. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(2):270-6.

15. Coleman SR, Katzel EB. Fat Grafting for Facial Filling and Regeneration. Clin Plast Surg. 2015;42(3):289-300.

16. Coleman SR. Facial augmentation with structural fat grafting. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(4):567-77.

17. Mailey B, Baker JL, Hosseini A, Collins J, Suliman A, Wallace AM, et al. Evaluation of Facial Volume Changes after Rejuvenation Surgery Using a 3-Dimensional Camera. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36(4):379-87.

18. Pessa JE, Rohrich RJ. Facial topography: clinical anatomy of the face. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2014.

19. Boneti C, Anakwenze C P, de la Torre J, Weaver TL, Collawn SS. Two-Year Follow-Up of Autologous Fat Grafting With LaserAssisted Facelifts. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76 Suppl 4:S260-3.

20. Wang W, Xie Y, Huang RL, Zhou J, Tanja H, Zhao P, et al. Facial Contouring by Targeted Restoration of Facial Fat Compartment Volume: The Midface. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(3):563-72.

1. Clínica Eduardo Furlani, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

EATF Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Resource Management, Project Management, Methodology, Conducting operations and/or experiments, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Visualization.

DBS Statistical analysis, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization.

MLMC Writing - Proofreading and Editing, Preview.

MVAB Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing -Proofing and Editing, Visualization.

Corresponding author: Eduardo Antonio Torres Furlani Rua Barbosa de Freitas, 1990, Aldeota, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil Zip Code: 60170-021 E-mail: eduardo@eduardofurlani.com.br

Article received: July 05, 2021.

Article accepted: December 13, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Institution: Clínica Eduardo Fulani Cirurgia Plástica, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter