Special Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Breast reconstructions: an evolutionary analysis of techniques and current state of the art

Reconstruções mamárias: análise evolutiva das técnicas e estado da arte atual

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The cancer that most affects women around the world is breast cancer. If the harm that the active disease is capable of causing was not enough, after the cure, the consequences continue to torment the lives of thousands of women. Furthermore, the psychological trauma of mutilation can have psychological repercussions that are difficult to control. Mastectomy saves the life of a woman with breast cancer; however, breast loss can keep the patient sick in the biopsychosocial aspect. Rebuilding the breasts then becomes crucial in the treatment of these women.

Methods: The study of the authors' public and personal collections allowed us to discuss the artistic and technical evolution of breast reconstructions over the years.

Results: Studies and reflections from plastic surgeons worldwide have enabled the standardization of a series of techniques and tools for breast reconstruction that will make up the arsenal of the modern surgeon. It includes techniques with local flaps, such as the plug flap and mammoplasty techniques, neighborhood flaps, such as the thoracodorsal flap, alloplastic materials (tissue expanders and prostheses), the numerous autologous flaps, including microsurgical flaps or, also, the combined techniques for the various types of cases. At the same time, the medical-hospital products industry has developed alloplastic materials (prostheses and expanders) that are more suitable and of better quality, which provide safer and more predictable reconstructions concerning the use of implants.

Conclusion: The current state of the art in breast reconstruction finds well-founded historical pillars and advanced technological aid, providing conditions for advanced treatments.

Keywords: Breast Neoplasms; Mastectomy; Breast; Breast Implantation; Mammaplasty; History; Art.

RESUMO

Introdução: O câncer que mais acomete mulheres em todo o mundo é o de mama. Não bastasse o mal que a doença ativa é capaz de causar, após a cura as sequelas continuam atormentando a vida de milhares de mulheres. O trauma psicológico de uma mutilação pode ter repercussões psicológicas de difícil controle. A mastectomia salva a vida da mulher com câncer mamário; entretanto, a perda da mama pode manter o biopsicossocial da paciente doente. Reconstruir as mamas se torna, então, tempo crucial no tratamento destas mulheres.

Métodos: O estudo dos acervos públicos e pessoais dos autores permitiram discorrer sobre a evolução artística e técnica das reconstruções mamárias através dos anos.

Resultados: Estudos e reflexões de cirurgiões plásticos em todo o mundo possibilitaram a padronização de uma série de técnica e ferramentas para reconstrução da mama, que vão compor o arsenal do cirurgião moderno. Existem várias, incluindo técnicas com retalhos locais, como o plug flap e as técnicas de mamoplastia, retalhos de vizinhança, como retalho toracodorsal, materiais aloplásticos (expansores teciduais e próteses), numerosos retalhos autólogos, incluindo retalhos microcirúrgicos ou, ainda, técnicas combinadas frente aos variados tipos de casos. Paralelamente, a indústria de produtos médico-hospitalares desenvolveu material aloplástico (próteses e expansores) mais adequados e de melhor qualidade, que propiciam reconstruções mais seguras e mais previsíveis no que concerne ao uso dos implantes.

Conclusão: O estado da arte atual da reconstrução mamária encontra pilares históricos bem fundamentados e auxílio tecnológico avançado, provendo condições para tratamentos refinados, de alta exigência e preparo do artista.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias da Mama; Mastectomia; Mama; Implante Mamário; Mamoplastia; História; Arte

INTRODUCTION

The cancer that most affects women around the world is breast cancer1. In addition to the harm that the active disease is capable of causing, after the cure, the consequences continue to torment the lives of thousands of women. The psychological trauma of mutilation can have psychological repercussions that are difficult to control. Mastectomy saves the life of a woman with breast cancer; however, breast loss can keep the patient sick in the biopsychosocial aspect2. Rebuilding the breasts then becomes crucial in the treatment of these women.

With the evolution of medicine, cancer treatment became less aggressive and enabled the advancement of techniques to reconstruct women’s femininity through the breast. As a result, local control of the disease can now be safely achieved with more conservative operations, offering the plastic surgeon an important place in the treatment. Furthermore, it was established that the biology of breast cancer is not altered by reconstruction, which does not compromise the proper treatment of the disease3.

Studies and reflections by plastic surgeons worldwide have enabled the standardization of a series of techniques and tools for breast reconstruction, which will make up the arsenal of the modern surgeon. It includes techniques with local flaps, such as the plug flap4 and mammoplasty techniques, neighborhood flaps, such as the thoracodorsal flap5, alloplastic materials (tissue expanders and prostheses), the numerous autologous flaps6, including microsurgical flaps or, also, the combined techniques for the various types of cases. At the same time, the medical-hospital products industry has developed alloplastic materials (prostheses and expanders) that are adequate and of better quality, which provide safer and more predictable reconstructions concerning the use of implants7.

Taking advantage of the history and evolution of surgical techniques allows the surgeon to understand the diagnosis and treatment better. Thus, History moves towards improvement and, like an artist who portrays all the world’s diversity on a canvas, towards the anatomical diversity of women, the more options the plastic surgeon has, the better his technical indication and the consequent result will be.

The evolution of anatomical knowledge, breast cancer physiology, oncology, anesthesia and, finally, surgery allowed the evolutionary history of breast reconstructions that we will discuss here. Evidence-based medicine combined with the artistic tone of plastic surgery transcends the human body, and they walked together since the beginning with Hippocrates, armed with a great capacity for clinical observation. However, with the knowledge he was given, he thought: “…and they appear hard tumors in the breast, some larger, and others smaller, that do not swell but that keep growing and getting harder. Hence, occluded cancers are born. When at last the cancers appear, the mouth becomes more bitter, and everything the patients eat tastes bitter to them, and if they want to give them more food, they refuse it and close their mouths. They start to delirious, the eyes are still and cannot see clearly, the pain born in the breast reaches the neck and shoulder blades, thirst sets in, the nipples become dry, and the whole body is emaciated. When patients reach this state, they do not recover and die from their illness. It is better not to apply any treatment in cases of occluded cancer because if treated, patients die quickly, but if not treated, they still last a long time…”3. The evolution of this knowledge has been significant up to the present day, and, in the complete lucidity of the 21st century, complex challenges are still faced in the daily lives of surgeons who treat the breast.

History

The magnitude of medical knowledge squandered today owes its toll to the discoveries of past centuries. For example, with the discovery of anesthesia in 1846, painless operations began, as everything that existed before “was just darkness of ignorance, suffering, fruitless attempts in the dark.” (Bertrand Gosset - Book: The Century of Surgeons, 1956)8.

In the nineteenth century, with Halsted9, surgeries were extensive and removed a large amount of skin, pectoral muscles and sometimes even the ribs, justified by the need to cure breast cancer. Thus, a population with important aesthetic, functional, social and psychological sequelae began, since the breast reconstruction of these patients was discouraged by Halsted himself, for fear of impairing the diagnosis of local recurrences of the disease and the healing process9.

With such aggressive surgeries, attempts to close the defect primarily and under tension were often unsuccessful. Dehiscence requiring closure by the second intention was not rare, causing great morbidity and mortality to the patients. Halsted modified his technique to alleviate this problem, using skin grafts to cover the defect, avoiding closure under tension, but with poor and even mutilating aesthetic results10.

The history of breast cancer treatment led to increasingly less aggressive behavior. In the 19th century, the use of autologous tissues marked the beginning of modern treatments for breast reconstruction. However, it was only in the second half of the 20th century that the concept of breast reconstruction after mastectomy became popular with the initial introduction of pedicled flaps and, subsequently, free flaps supported by perforators. The first successful reconstruction was described by Czerny, in 189511, a German surgeon who autotransplanted a lipoma from the lumbar region to the site of previous subcutaneous mastectomy; according to the author, the reconstructed breast maintained good shape, with a one-year follow-up.

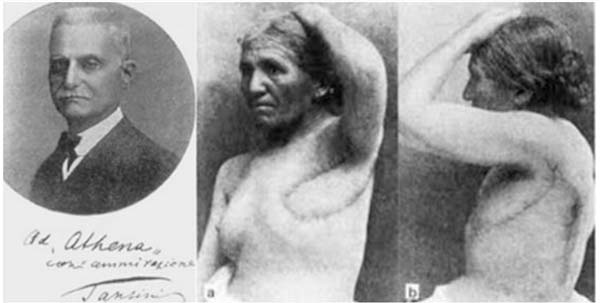

Soon after Tansini, in Italy, in 189712, he began his studies and performed the first rotation of the latissimus dorsi flap (Figure 1), used at that time to cover a defect in the chest wall, an incipient breast reconstruction. This procedure was not very well received and soon fell into disuse due to the belief that immediate reconstruction would make it challenging to detect local recurrence, a concept spread by Hasted and which was perpetuated for many years12. Tansini (1906)13 advocated complete ablation of the mammary gland as a way to reduce recurrences. He was also an advocate of expanding surgical margins to ensure complete removal of the disease, a principle adopted in the techniques most used in Europe in the first two decades of the 20th century.

At the beginning of the next century, the French surgeon Ombredanne (1983)14 described the use of the pectoralis minor muscle flap for immediate breast reconstruction, in which the skin was repaired by a thoracoabdominal flap pedicled in the axillary region. However, following what happened with Tansini (1906)13, the technique was not well received for fear of harming the monitoring of the disease. Shortly after that, in 1917, Bartlett8 published six breast reconstruction cases, post-subcutaneous mastectomy for cystic fibrous mastitis, with a fat graft taken from the anterior abdominal regions, external thighs and gluteal regions. According to his technique, to remove subcutaneous fat approximately 50% larger than the removed breast tissue was recommended to supply the anterior volume of the breast added to the graft atrophy that always occurred. To reduce the degree of resorption, dermal or dermofat grafts were used, with the epidermis decorticated. However, they also proved to be insufficient to maintain the desired breast size.

Kleinschmidt, in 192414, following reasoning similar to that of Ombredanne (1983)14, in the same period, developed a local lateral skin flap, based on the axilla, which rotated itself to cover the defect and form the mammary mound15.

Sometime later, important surgeons in the scientific evolution of the last century, Gillies and Millard (1957)10 and Holdsworth (1956)16, developed breast reconstruction techniques using tubular skin flaps, obtained in areas other than the defect, aiming at the reconstruction of the amputated glandular volume17. These were flaps from the abdomen or lower chest, based on a tubular pedicle and through multiple operative procedures, and which were transferred to the mastectomized area. The reconstructive process was time-consuming, took months or years, and had high morbidity. These procedures, associated with poor aesthetic results, did not establish the technique among surgeons in the 1940s.

In 1959, Longacre et al.18, using decorticated submammary neighborhood flap, obtained in the inframammary region and inserted into the breast to provide volume after subcutaneous mastectomy, observed volume maintenance and no signs of resorption after a follow-up of up to eleven years, attributing the preservation of an extensive subcutaneous network of blood vessels. In 1956, Holdsworth16 published a tubular flap from the pendular portion of the opposite breast, which was transferred to the mastectomy defect. In 1973, Pontes19 refined the use of the contralateral breast as a donor area, describing a technique that used a flap consisting of its inner half to reconstruct the lost breast in a single time.

Reconstructions with implants

At the beginning of the last century, they developed alloplastic materials as an alternative to autologous reconstructions. The idea started using a concept proposed by Gersuny in 1899 20, when he introduced, through injection, paraffin to enlarge the breast20. The innovative idea led other surgeons to experiment with other injectable products, vegetable oils, lanolin, silicone and beeswax. However, this technique was soon abandoned due to the numerous and severe local complications, such as paraffinomas, ulcerations and fistulas, in addition to pulmonary, cerebral and retinal embolisms.

Several materials and attempts were made to obtain the best type of breast implant from then on. Nevertheless, it was only in the 1960s that the first silicone prosthesis was implanted in humans, in Texas, by Blocksma and Braley21, formed by a thick outer layer and filled with a moderately cohesive silicone gel, in addition to seams and fixation seals. Then came the future of breast implants. However, it took much evolution to reach the modern silicone prostheses we have today.

In 1965, the first saline-filled prostheses also appeared in France. This type of filling introduced some advantages, such as the possibility of insufflation in loco, allowing insertion through smaller incisions and a better and more acceptable contracture rate than the previous one. However, the difficulties with the high deflation rates and consistency away from the natural breast bothered patients and surgeons22.

In order to overcome these difficulties, Daher, in 1972, started some reconstruction cases with the use of successively replaced silicone prostheses, initially placing a smaller one and changing every 90 days for a larger one, thus achieving skin expansion. This idea, although original, was replaced by the ingenious publication by Radovan23, in the same decade, of tissue expanders, which allow the placement of larger implants under pre-expanded skin. This has rekindled the use and popularity of breast reconstruction with tissue expanders in various shapes, sizes, shapes and textures. In addition, modern expanders have been increasingly improved to guarantee an aesthetic result for both the reconstructed breast and the contralateral breast, especially concerning its symmetry23.

Still in the early 70s (1972), the Plastic Surgery Service at the Hospital das Forças Armadas, in Brasília, in partnership with the oncology service, with very advanced positions for the time, admitted more conservative resections and, above all, indicating subcutaneous mastectomies as a preventive procedure, also known as adenectomies. It was the beginning of surgeries today called skin sparring. “We performed an emptying of the breasts, leaving skinny dermocutaneous flaps that covered the silicone implants, produced by ‘dow corning,’ and with exciting immediate results. Soon after, we evolved to the same procedure with submuscular implants.” (Daher, 1972)

In 1984, Becker24 described an expander with two compartments inside, one filled with silicone gel and the other empty to be filled later with saline solution, according to the desired size. The Becker expander was a pioneer in one-stage breast reconstruction, eliminating the need for a second surgical procedure where permanent silicone implants would replace the expanders.

Most breast reconstructions with expanders had satisfactory results over time until Clough et al. (2001)25 reported a deterioration of the result over the years. Most results were acceptable initially but got worse as time went on, probably due to asymmetry and aging of the implants. Elliot and Hartrampf (1990)29 listed several causes that could limit this technique, including the great need for visits to the doctor’s office (for the gradual expansion of the tissue), the risk of perforation of the expander with the consequent need for replacement. Others criticized the expansion technique for taking too long and requiring several subsequent surgical revisions. Gradually, interest in breast reconstructions with autogenous tissues gained ground in the 80s26.

Over time, the goals of breast reconstructions became more refined. Surgeons and patients started to look for more precise contours, better symmetry and breast positioning. However, these goals were commonly limited due to the defects created by mastectomy. The mastectomy technique is the main factor influencing the outcome of the reconstruction. These techniques have also undergone essential evolutions, from the radical removal of all breast tissue and adjacent tissues to the tissue-sparing philosophy. The skin-sparing mastectomy technique preserves the entire cutaneous envelope of the breast, resulting in fewer scars and good quality remaining skin coverage on the chest wall.

Myocutaneous flaps

In the late 1970s, we entered the era of myocutaneous flaps, initially the latissimus dorsi. Tansini described this flap in 190613, but its systematic use for breast reconstructions is due to McCraw (1978)27 and Bostwick (1979)28, who created the possibility of taking skin from the back to the mastectomy region, it can be combined with a silicone implant to provide volume to the region. With the advent of expanders, the remaining tissues of the anterior chest wall were expanded, often with the latissimus dorsi flap already taken to the region.

Despite being timeless and used on a large scale until today, the latissimus dorsi flap, analyzed chronologically, was replaced by the transverse rectus abdominis (TRAM) flap. The first descriptions of using a pedicled musculocutaneous flap based on the rectus abdominis muscle for chest and abdominal wall reconstructions were by Dreaver in 198129, in the vertical form. Later, in 1979, Robins30 described the same vertical flap, but to reconstruct the breasts, which then, in 1982, was modified by Hartrampf34, and made in a transverse shape, give the origin of the transverse rectus abdominis muscle flap - TRAM, quickly becoming an essential alternative for breast reconstructions.

Oncology and mastology evolved to more conservative resections, quadrantectomies, which required other solutions from plastic surgery, now no longer for the total reconstruction of the breasts but their partial reconstruction. Thus, when the plug flap appeared - an island flap of the breast published by Daher in 19934, this first flap in an island of the breast, which we call the plug flap, is a cylinder of breast tissue, pedicled in the rib cage, topped by a fragment of skin or areola, which will be transposed to the quadrantectomy region. This is a safe flap, as it has pedicles based on anatomical studies performed by the author, who dissected twenty breasts raised in the form of a tent, exposing the vascularization of the anterior chest wall.

The free patches

Microsurgery was the most recent advancements that made it possible to develop flaps with more limited vascularization or even performed reconstructions with flaps brought from a distance and minor damage to the donor areas.

In 1976, Fujino32 performed the first free flap transfer for breast reconstruction from a portion of the gluteus maximus muscle. Holmstrom performed the first free abdominal flap in 197933. The socalled free abdominal flap was designed based on an abdominoplasty skin flap on unilateral, inferior epigastric vessels. Since then, autogenous free flap transfer has become the method of choice in many breast reconstruction centers.

With the popularization of gluteal flaps in 1990, Allen et al. performed the first superior gluteal artery flap (SGAP) and, in 2006, Allen et al.38 described the use of a flap based on the inferior gluteal artery (IGAP) for breast reconstruction, with an unpleasant scar resulting in the inferior gluteal fold34.

In recent years, with the increase in conservative surgeries indicated by mastologists and the use of quadrantectomies, dermoglandular neighborhood flaps have taken over. Island flaps in the thoracic region gain space, such as the plug flaps by Daher (1993)4 and in 2003, with Graf et al.35, who created a technique using a chest wall flap with a bipedicled muscle flap from the pectoralis major muscle. in a vertical scar.

DISCUSSION

The plastic surgeons’ desire for breast reconstruction may find among its motivations more specific and deeper psychoanalytic explanations, in addition to the desire to reconstruct the specialty itself. We are used to saying that Melaine Klein, an eminent psychoanalyst of the last century, formulated her theories about the good breast and the bad breast, converging with our search for the whole, beautiful, unmutilated breast or with the recovered mutilation.

The advent of silicone prosthesis was the outstanding contribution of engineering and industry to plastic surgery and a critical point in the chapter of breast surgery in general. It served cosmetic surgery for augmentation mammoplasty and became a powerful tool weapon for breast reconstruction soldiers. It served for the first attempts to create breast volume where there was none. However, its use was initially limited because the reconstruction cases followed mastectomies performed using Halsted, Stewart, Pattey and Pattey techniques. The first three performed extensive skin resections with skinny flaps, which would hardly support silicone in an attempt at reconstruction.

The proposal of reconstruction by dividing the remaining breasts, although extremely ingenious and of great value to the patients who used it, was abandoned, above all, by the enormous resistance of mastologists. At the time, they were highly conservative in the face of precarious imaging exams (the most advanced mammography device manufactured by France could see tumors 1 cm above, which is very little by today’s standards). Moreover, they feared the hypothesis that we were taking potentially cancerous glandular tissue; after all, the principles of bilaterality of certain tumors to the contralateral wall were already known.

Nevertheless, in the early 70s, two facts began to change the course of breast reconstructions: more daring breast cancer specialists pushed for more conservative surgeries, with more minor skin resections, leaving slightly thicker flaps, reaching the modified Pattey technique that, with horizontal incision and thicker flaps, he dared to preserve the greater pectoralis or both, thus protecting the anterior pillar of the axillary hollow. This improvement in conditions in the area of mastectomy led plastic surgeons to attempt, albeit timid, to use the silicone implant, whichever fit, which began with breaking the other taboo of conservative oncologists: reconstructions could only take five years later the mastectomy. The boldness of the more progressive breast cancer specialists associated with the everimproving improvement of plastic surgeons showed that the reconstruction does not worsen the prognosis, but, on the contrary, it improves by providing the patient with the quality of life.

In the last two decades, tissue engineering research has been studying the possibility of developing ultra-realistic synthetic fabrics. The potential use of these techniques in breast reconstruction can enable the use of autologous tissues without the need for a satisfactory donor area, in addition to avoiding the morbidities involved in their mobilization.

The acellular dermal matrix, which was initially used in breast augmentation revisions to prevent rippling and changes in breast contour, has lately been used in breast reconstructions associated with a dual plane or total submuscular implants. Its use became better known in 2005, after a case report of its use as a sling to cover the inferolateral pole35. The use of acellular dermal matrix has two major advantages: coverage of the silicone implant in the inferolateral pole when the pectoralis major muscle is absent or insufficient; and less postoperative pain complaint, less morbidity of the donor area and better aesthetic results36-38.

Like art, the evolution of plastic surgery has no endpoint; it evolves according to human existence. Its relationship with the knowledge and treatment of breast cancer is increasingly mixed. We are witnessing the emergence of a new aspect of plastic surgery, called oncoplastic surgery, which requires more profound knowledge about the conduction and advanced techniques for treating breast cancer, from mastectomies, indications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy and its proposal for debulking.

Thus, the current state of the art in breast reconstruction finds well-founded historical pillars and advanced technological support, providing conditions for refined treatments, which are highly demanding and prepared by the artist. It is up to us surgeons to know how everything got here and be aware of modernity and the newest evidence that is released to us every day, as only then will we be able to dispense the proper best treatment for reconstructed breasts.

REFERENCES

1. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2012: incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2011.

2. Cosac OM, Camara Filho JPP, Cammarota MC, Lamartine JD, Daher JC, Borgatto MS, et al. Salvage breast reconstruction: the importance of myocutaneous flaps. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013 Mar;28(1):92-9.

3. Peto R, Boreham J, Clarke M, Davies C, Beral V. UK and USA breast cancer deaths down 25% in year 2000 at ages 20-69 years. Lancet. 2000 Mai;355(9217):1822.

4. Daher JC. Breast island flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 1993 Mar;30(3):217-23.

5. Holmström H, Lossing C. The lateral thoracodorsal flap in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986 Jun;77(6):933-43.

6. Serletti JM, Fosnot J, Nelson JA, Disa JJ, Bucky LP. Breast reconstruction after breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Jun;127(6):124e-35e.

7. Petit JY, Lê MG, Mouriesse H, Rietjens M, Gill P, Contesso G, et al. Can breast reconstruction with gel-filled silicone implants increase the risk of death and second primary cancer in patients treated by mastectomy for breast cancer?. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994 Jul;94(1):115-9.

8. Bartlett W. Anatomic substitute for the female breast. Ann Surg. 1917 Ago;66(2):208-16.

9. Halsted WS. I. The result of operations for the cure of cancer of the breast performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital from June, 1889 to January, 1894. Ann Surg. 1984 Nov;20(5):497-555.

10. Gillies H, Millard JR. The principles and art of plastic surgery. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1957. p. 175-9.

11. Czerny V. Plastischer ersatz der brustdrusse durch ein lipom. Verhand Deustsch Gesellsch Chir. 1985;24:2-217.

12. Escudero FJ. Evolución histórica de la reconstrucción mamaria. An Sist Sanit Navarra. 2005;28(Supl 2):7-18.

13. Tansini I. Sopra il mio nuovo processor di amputazione della mammella. (coverage of the anterior chest wall following mastectomy). Guz Mal Ital. 1906;57:141.

14. Teimourian B, Adham MN. Louis Ombredanne and the origin of muscle flap use for immediate breast mound reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983 Dez;72(6):905-10.

15. Wickman M. Breast reconstruction--past achievements, current status and future goals. Scand J Plast Reconstr Hand Surg. 1995 Jun;29(2):81-100.

16. Holdsworth DW. A method of reconstructing the breast. Br J Plast Surg. 1956;9:161-2.

17. Glicenstein J. Histoire de l’augmentation mammaire. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 1993;38:647-55.

18. Longacre JJ, Stefano GA, Holmstrand K. Breast reconstruction with local derma and fat pedicle flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1959;24:563-76.

19. Pontes R. Single stage reconstruction of the missing breast. Br J Plast Surg. 1973 Out;26(4):377-80.

20. Muller GH. Gersuny em 1899. Les implants mammaires et leur histoire. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1996 Dez;41(6):666-75.

21. Blocksma R, Braley S. The silicones in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965 Abr;35:366-70.

22. Goldwyn RM. Prótese salina. The paraffin story. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;65:517-24.

23. Radovan C. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy using the temporary expander. Plast Reconstr Surg 1982 Fev;69(2):195-208.

24. Becker H. Breast reconstruction using an inflatable breast implant with detachable reservoir. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984 Abr;73(4):67883.

25. Clough KB, O’Donoghue JM, Fitoussi AD, Vlastos G, Falcou MC. Prospective evaluation of late cosmetic results following breast reconstruction: II. Tram flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1710-6.

26. Elliott LF, Hartrampf Junior CR. Breast reconstruction: progress in the past decade. World J Surg. 1990 Nov/Dez;14(6):763-75.

27. McCraw JB, Penix JO, Baker JW. Repair of major defects of the chest wall and spine with the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978 Ago;62(2):197-206.

28. Bostwick J, Nahai F, Wallace JG, Vasconez LO. Sixty latissumus dorsi flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63(1):31-3.

29. Drever MJ. Total breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1981 Jul;7(1):54-61.

30. Robbins TH. Rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap for breast reconstruction. Aust N Z J Surg. 1979 Out;49(5):527-30.

31. Hartrampf CR, Scheflan M, Black PW. Brest reconstruction whit a transverse abdominal island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:21625.

32. Fujino T, Harashina T, Enomoto K. Primary breast reconstruction after a standard radical mastectomy by a free flap transfer. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976 Set;58(3):371-4.

33. Holmström H. The free abdominoplasty flap and its use in breast reconstruction. An experimental study and clinical case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;13(3):423-7.

34. Allen RJ, Levine JL, Granzow JW. The in-the-crease inferior gluteal artery perforator flap for breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Ago;118(2):333-9.

35. Graf R, Araujo LR, Rippel R, Graça Neto L, Pace DT, Biggs T. Reduction mammaplasty and mastopexy using the vertical scar and thoracic wall flap technique. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003 Jan/ Fev;27(1):6-12.

36. Johnson GW. Central core reduction mammoplasties and Marlex suspension of breast tissue. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1981;5(1):77-84.

37. Góes JC. Periareolar mammaplasty: double skin technique with application of polyglactine or mixed mesh. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996 Abr;97(5):959-68.

38. Breuing KH, Warren SM. Immediate bilateral breast reconstruction with implants and inferolateral AlloDerm slings. Ann Plast Surg. 2005 Set;55(3):232-9.

1. Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Brasília, DF, Brazil

JCD Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

COPC Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

TMAF Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

PCETT Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Funding Acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing.

OMC Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

SVS Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author: Tristão Maurício de Aquino Filho SHIS, QI 7, Conj. F - Lago Sul, Brasília - DF, Brazil. Zip Code: 71615-660, E-mail: dr.tristaomauricio@gmail.com

Article received: September 30, 2020.

Article accepted: January 10, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter