Case Report - Year 2022 - Volume 37 - Issue 2

Surgical treatment of penoscrotal lymphedema in a patient with Milroy's disease: case report

Tratamento cirúrgico de linfedema penoescrotal em um paciente com doença de Milroy: relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Milroy disease manifests itself as lymphedema of the lower limbs and genital region, which causes physical and social damage.

Case Report: A case of severe-scrotal lymphedema in a patient with Milroy disease. Surgical resection of the affected tissue and reconstruction with local flaps and skin graft were performed. Discussion: Milroy disease is a rare autosomal dominant disease. The clinical presentation is progressive and results from hypoplasia of the lymphatic vessels of the lower limbs. Treatment in advanced cases is mainly surgical.

Conclusion: In the case of a patient with Milroy disease and severe penoscrotal lymphedema, surgical treatment is a good option. The use of parascrotal flaps for scrotoplasty associated with a graft to recover the penis provides a good functional result.

Keywords: Lymphedema; Scrotum; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Urologic surgical procedures, male; Genital diseases, male; Congenital abnormalities.

RESUMO

Introdução: A doença de Milroy manifesta-se como linfedema de membros inferiores e região genital, o que provoca prejuízos físicos e sociais.

Relato de Caso: Reporta-se um caso de linfedema penoescrotal severo em um paciente com doença de Milroy. Foi realizada a ressecção cirúrgica do tecido afetado e a reconstrução com retalhos locais e enxerto de pele.

Discussão: A doença de Milroy é rara, de caráter autossômico dominante. Sua apresentação clínica é progressiva e decorre da hipoplasia dos vasos linfáticos dos membros inferiores. O tratamento em casos avançados é iminentemente cirúrgico.

Conclusão: No caso apresentado, o tratamento cirúrgico é uma boa opção. O uso de retalho paraescrotal para escrotoplastia associado ao enxerto para cobertura do pênis proporciona bom resultado funcional.

Palavras-chave: Linfedema; Escroto; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Procedimentos cirúrgicos urológicos masculinos; Doenças dos genitais masculinos; Anormalidades congênitas

INTRODUCTION

Penoscrotal lymphedema is relatively rare, especially in developed countries1. It is categorized as primary, due to obstruction, hypoplasia or lymphatic malformations, or secondary to several causes such as filariasis, lymphogranuloma venereum, radiation and malignancy2. It often affects sexual and voiding function, predisposes to infections, and makes locomotion difficult, which reduces the quality of life, with physical and psychosocial repercussions3.

Surgical treatment is presented as the best alternative, in cases with large dimensions, through surgical excision followed by reconstruction with flaps and grafts4. Despite this, management is challenging. This paper presents a surgical alternative for an uncommon disease and a therapeutic approach not standardized in the literature. This is followed by a brief discussion using an updated bibliographic review.

CASE REPORT

This is a 22-year-old male patient, born in a nonendemic area of filariasis in Minas Gerais, referred for plastic surgery evaluation at the Hospital das Clínicas of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (HC-UFMG). He reported that, from birth, his lower limbs, scrotum, and penis began to progressively edema (cold and soft edema), with evolution to aesthetic and functional impairment (voiding, sexual and locomotor). He informed that his family, on his mother’s side, has been affected for three generations by the same condition and that his brothers were also affected but evolving with lesser proportions.

There was massive scrotal lymphedema on physical examination with dimensions of 50cm x 30cm x 20cm, lymphedema of the foreskin with non-visible and non-externalizable glans. The skin of the lower limbs, scrotum and penis was infiltrated, hardened and with exophytic, hyperkeratotic nodules, some with central, dry ulcers. The testes were not palpable and had negative transillumination (Figure 1). There was a need for a wheelchair to travel long distances, and he could not stand orthostasis for a long time.

The patient had no comorbidities, the workup for filariasis was negative, and the abdomen and pelvis computed tomography showed an image compatible with penoscrotal lymphedema. He was classified as ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) II.

On April 16, 2019, surgery was started with antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin. The patient was placed in lithotomy, extensive antisepsis, pubic nodule biopsy and urethral swab (for anatomopathology and culture, respectively) were performed, followed by indwelling bladder catheterization with the aid of preputial repair sutures at 3 and 9am. A longitudinal incision was made in the median scrotal raphe up to the penile base, with bilateral exploration by dissection in planes. Thus, the testes were identified in a cranial position, close to the external inguinal ring, fixing them. The right testicle was reduced in size, and the left testicle had its usual size.

Postectomy was performed using a double circular incision technique, preserving a circular band of the original foreskin of approximately 3cm in length from the new coronal sulcus (Figure 2).

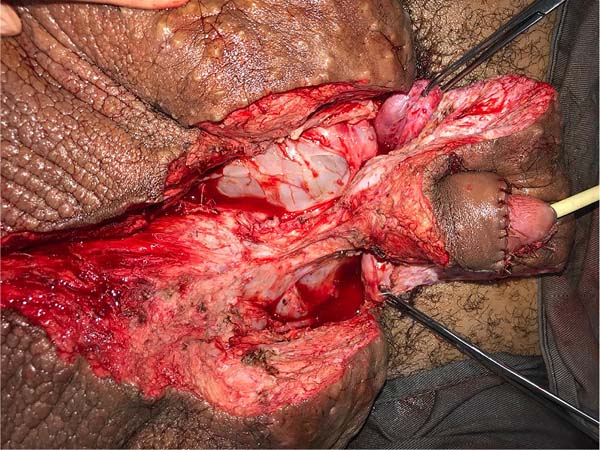

This was followed by the subdermal dissection of two parascrotal flaps in the transition with healthy skin (24cm x 10cm) and an inverted “V” perineal flap (7cm), with subsequent excision of the scrotal excesses (Figure 3). The parascrotal flaps were bipartite, the cranial part being used for pubopenic synthesis at the level of the superficial portion of the suspensory ligament and the body of the penis, with dorsal and ventral sagittal sutures (4-0 nylon in the pubic region and 4-0 polyglactin in the penile region).

The scrotum was rebuilt by joining the caudal portion of the parascrotal flaps to the midline, fixing the cranial portion to the penile base with adhesion sutures (3-0 polyglactin) and closing the caudal portion in a “W” shape next to the perineal flap (nylon 4-0).

It was concluded by placing two laminar drains in the new scrotum and the usual synthesis of the remaining incisions in two planes. The penis was immobilized vertically with a gauze dressing, and the scrotum was bandaged with a sterile bandage in the form of a scrotal brace (Figure 4).

Cultures taken intraoperatively did not result in bacterial growth. The bladder catheter was maintained for two days. The dressing was changed daily from the third postoperative day (POD). The drains were removed on the 5th POD after a flow rate of less than 30ml in the previous 24 hours. On the 7th POD, a fetid, greenish secretion was coming out of the ventral portion of the penile suture; secretion cultures were collected, suture stitches were removed alternately, and empirical antibiotic therapy was started (ceftriaxone + gentamicin). Dressings were changed at shorter intervals (8h).

The following morning, the darkened and swollen flaps could be seen, especially in the portion covering the left half of the penile surface (Figure 5). The remainder of the ventral suture was removed, and the wound aspect worsened. According to the antibiogram, cultures were positive for Klebsiella sp., which prompted antibiotic escalation (piperacillin-tazobactam + vancomycin).

On the 10th POD, there was already delimitation of the necrosis, and a new approach was performed for debridement of necrotic tissues up to Buck’s fascia (Figure 6), collection of new cultures and coverage with a partial thickness graft (0.6mm), taken from the left thigh and sutured circumferentially to the penis, with suture in its ventral midline. A new dressing was performed with petrolatum gauze + sterile hydrophobic cotton, maintained for five days.

At the first change, diffuse losses of the graft placed were observed, with punctate greenish collections under some sites. The new culture was positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, requiring a new antibiotic (tigecycline) escalation. It evolved with good healing of the unaffected areas, but with bloody areas at 12-5 am at the penile base, but with a granular appearance (Figure 7).

He was discharged on the 25th DPO, with serial returns at 15, 30, 60 and 120 days. The patient presented voluntary urination with satisfactory voiding control and a non-painful, functional erection with preserved ejaculation. Aesthetically, the final result was poor, with dorsolateral scars on the penis, hypertrophic scars in the pubic region and deviation of the flaccid penile shaft to the left by 90° in the axial plane (Figure 8). The patient, however, chose not to perform new approaches, reporting being satisfied with the results.

The anatomopathological study showed chronic lymphedema, with a piece weight of 15.736 kilograms and dimensions of 48 x 28 x 17cm. There was no presence of microfilariae. At three months postoperatively, the spermogram showed oligospermia, with reduced vitality in the sample, and seminal fluid culture without bacterial growth. The urodynamic test was within the normal range.

DISCUSSION

In the case presented, the patient is affected by Milroy’s disease, rare, primary lymphedema of autosomal dominant inheritance that affects the lower limbs and genital region. It is characterized by mutations in the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3) gene, responsible for developing lymphatic vessels5. These patients are affected by massive edema, fibrosis and skin hardening that compromises voiding and sexual function, impairs mobility and social interaction6.

The management of large penoscrotal lymphedema is challenging. Due to the pathophysiology of Milroy’s disease, the condition does not obtain results with conservative therapy such as lymphangioplasty since there is a hypoplasia of the lymphatic vessels of the lower limbs7. Thus, the current literature describes lymphangiectomy (surgical excision of the affected skin and subcutaneous tissue) as the treatment of choice, especially in cases of advanced disease and associated fibrosis8.

The patient, previously aware of the risks of orchiectomy, poor evolution of scars, and flaps, underwent surgical management. The staggered approach allowed relatively simple reconstructive methods when complications occurred, something that might have been impossible if more complex reconstructive options had already been dispensed with from the start (gracile flaps, Singapore flaps, or microsurgical flaps). Several authors have described satisfactory experiences with radical resection and reconstruction with flaps and grafts. The techniques are similar, and scrotoplasty is frequently performed with posterior perineal and parascrotal flaps, as in the case presented9.

The technique of covering the penis is variable, but previous experiences have shown superior aesthetic and functional results in partial-thickness grafts4. The option of reconstructing the penile coverage with parascrotal flaps does not provide a good mimicry of the original skin of the penis, which is rough and darkened, as the scrotal skin is affected by the disease. Despite being frowned upon for not having the vascular security provided by a flap, the use of grafts was the one that presented the best aesthetic result in the case in question, even having been afflicted by an infectious process.

Healing by the second intention of small areas on the penis is possible since there was no formation of retractions or hypertrophic scars, but it is not desirable due to the loss of aesthetic homogeneity of the penile body. The use of the skin of the foreskin is also not recommended in this case because when all the tissue is removed from the base of the penis, the lymphatic drainage of the remaining skin is interrupted, or it inevitably progresses to recurrence edema10. The graft donor area in Milroy’s disease, if compromised by fibrosis, can result in an extensive and hypertrophic scar4.

The operative environment is contaminated by skin bacteria under moist folds and exposed to urinary and possibly fecal content, depending on the extent of the disease; in addition, the patient’s immunity is compromised by lymphatic involvement. Dandapat et al.4 reported infection in 10.6% of cases in the largest series of cases described.

Overflow urinary incontinence is common in these patients, as are different levels of testicular involvement, as it compromises temperature maintenance and impairs spermatogenesis. One of the alternatives that seem to alleviate the loss of fertility is using a scrotal skin flap since it has the cremasteric muscle, which is thermosensitive11.

In the case of patients with Milroy’s disease, the regional tissues are also affected, limiting the option of pedicled flaps for reconstruction and hampering the healing process in the manipulated areas. Histological evidence shows that removing the entire affected dermis can be associated with better aesthetic results. Despite this, the recurrence of lymphedema in Milroy’s disease reaches 50%12.

Despite not preventing the recurrence of lymphedema, surgical intervention provides the patient with a better quality of life. Most previous studies show improvement in sexual and voiding function, mobility, activities of daily living, socialization, and pain reduction through subjective assessment of patients13. Patients should be advised preoperatively about the inherent risks and the possibility of long postoperative hospitalization for the necessary care, as in the case reported, in which the patient remained hospitalized for 25 days3.

CONCLUSION

Surgical treatment of genital lymphedema in Milroy’s disease is complex. It was evident that the use of grafts provides the best local aesthetic aspect for coverage of the penis but requires the presence of a considerable scar in the donor area, especially if the disease compromises healing.

The parascrotal flaps showed good results only in the scrotal portion of the wound, resisting the infectious process, which was not true for using these flaps in the penile body.

There was no regression of the edema in the subglandar portion (possibly caused by the underlying disease), which generated an unpleasant aesthetic aspect in the body-glans transition, allowing us to assess the maintenance of skin bridges during the postectomy is inadvisable from the point of aesthetic view.

REFERENCES

1. Champaneria MC, Workman A, Kao H, Ray AO, Hill M. Reconstruction of massive localised lymphoedema of the scrotum with a novel fasciocutaneous flap: A rare case presentation and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(2):281-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2012.06.024

2. Grada AA, Phillips TJ. Lymphedema: Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(6):1009-20. PMID: 29132848 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.022

3. Wisenbaugh E, Moskowitz D, Gelman J. Reconstruction of Massive Localized Lymphedema of the Scrotum: Results, Complications, and Quality of Life Improvements. Urology. 2018;112:176-80. PMID: 27865752 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.09.063

4. Dandapat MC, Mohapatro SK, Patro SK. Elephantiasis of the penis and scrotum. A review of 350 cases. Am J Surg. 1985;149(5):686-90. PMID: 3993854

5. Dai T, Li B, He B, Yan L, Gu L, Liu X, et al. A novel mutation in the conserved sequence of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 leads to primary lymphoedema. J Int Med Res. 2018;46(8):3162-71. PMID: 29896974 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060518773264

6. Torio-Padron N, Stark GB, Földi E, Simunovic F. Treatment of male genital lymphedema: an integrated concept. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68(2):262-8. PMID: 25456280 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2014.10.003/j.bjps.2014.10.003

7. Kung TA, Champaneria MC, Maki JH, Neligan PC. Current Concepts in the Surgical Management of Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(4):1003e-13e. PMID: 28350684 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003218

8. Scaglioni MF, Uyulmaz S. Lymphovenous anastomosis and debulking procedure for treatment of combined severe lower extremity and genital lymphedema: A case report. Microsurgery. 2018;38(8):907-11. PMID: 29719080 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.30331

9. Butler C, Osterberg C, Horvai A, Breyer B. Milroy’s disease and scrotal lymphoedema: pathological insight. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215396. PMID: 27118755 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-215396

10. Apesos J, Anigian G. Reconstruction of penile and scrotal lymphedema. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;27(6):570-3. PMID: 1793244 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000637-199112000-00010

11. Ferdinand NW, Peter BK. Bilateral Scrotal Flaps: A Novel Ideain the Management of Massive Scrotal Lymphoedema. J Surg. 2018;6(4):92-6.

12. Lobato RC, Zatz RF, Cintra Junior W, Modolin MLA, Chi A, Van Dunem Filipe de Almeida YK, et al. Surgical treatment of a penoscrotal massive localized lymphedema: Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;59:84-9. PMID: 31121427 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.05.022

13. Aulia I, Yessica EC. Surgical management of male genital lymphedema: A systematic review. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47(1):3-8. PMID: 31964116 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2019.01123

1. Faculdade Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

2. Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brazil

3. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Hospital das Clínicas, Belo Horizonte, MG,

Brazil

Institution: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Hospital das Clínicas, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

JRFS Data Curation, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation.

MLMR Writing - Original Draft Preparation.

SASRF Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing - Original Draft Preparation.

LDC Realization of operations and/or trials.

CLT Realization of operations and/or trials.

ACJ Project Administration, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author: Sergio Antonio Saldanha Rodrigues Filho Av. Professor Alfredo Balena, 110, Santa Efigênia, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, Zip Code: 30130-100, E-mail: jrfsouza97@gmail.com

Article received: February 01, 2021.

Article accepted: July 14, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter