Review Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Ideal positioning of the lower lateral cartilages associated with the optimization of the external nasal valve

Posicionamento ideal das cartilagens laterais inferiores associado à otimização da válvula nasal externa

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The Lower Lateral Cartilages (LLC) positioning is directly related to good nasal functionality. When these cartilages have cephalic malpositioning, the lateral wall of the external nasal valve is not adequately supported, which can lead to valvular insufficiency. The objective is to define the ideal anatomical positioning of the LLC associated with optimizing the external nasal valve.

Methods: Review narrative literature in the following databases: SciELO, LILACS and Medline. The descriptors used were: "nasal cartilages,"; "nasal obstruction," and "rhinoplasty," being selected 15 essential articles for the understanding of the subject. Literature review: Positioning the lateral crura of the LLC forms the contour of the nasal tip and provides stability to the lateral wall of the external nasal valve. Constantian defined the ideal positioning of the lateral crura of the LLC at the margin of the nasal alae should be 45° or less. For Toriumi, the angle is measured from the lateral crura of the LLC concerning the midsagittal plane, and the appropriate value is approximately 45°. For Silva, the positioning of the LLC is measured by the angle of divergence between the LLCs, and its appropriate value is approximately 90°.

Conclusion: The external nasal valve works better when the LLCs are well-positioned, namely: the angle formed between the lateral edge of the LLCs and the alar margin is close to 45° or less; the angle formed between the LLC and the midsagittal plane is close to 45°; the divergence angle formed between the LLC is close to 90°.

Keywords: Nasal obstruction; Nose; Nasal cartilages; Rhinoplasty; Breathing.

RESUMO

Introdução: O posicionamento das Cartilagens Laterais Inferiores (CLI) está diretamente relacionado à boa funcionalidade nasal. Quando essas cartilagens apresentam um mau posicionamento cefálico, a parede lateral da válvula nasal externa fica sem suporte adequado, podendo levar à insuficiência valvular. O objetivo é definir qual o posicionamento anatômico ideal das CLI associado à otimização da válvula nasal externa.

Métodos: Revisão de literatura narrativa nas seguintes bases de dados: SciELO, LILACS e Medline. Os descritores utilizados foram: "cartilagens nasais"; "obstrução nasal" e "rinoplastia", sendo selecionados 15 artigos essenciais para o entendimento do assunto. Revisão de literatura: O posicionamento do ramo lateral das CLI forma o contorno da ponta nasal e dá estabilidade à parede lateral da válvula nasal externa. Constantian definiu que o posicionamento ideal do ramo lateral das CLI à margem da asa nasal deve ser 45° ou menos. Para Toriumi, o ângulo é mensurado a partir do ramo lateral das CLI em relação ao plano sagital mediano e o valor adequado é de aproximadamente 45°. Para Silva, o posicionamento das CLI é mensurado pelo ângulo de divergência entre as CLI e tem como valor apropriado aproximadamente 90°.

Conclusão: A válvula nasal externa apresenta melhor funcionamento quando as CLI estão bem posicionadas, a saber: o ângulo formado entre a borda lateral das CLI e a margem alar é próximo de 45° ou menos; o ângulo formado entre as CLI e o plano sagital mediano é próximo de 45°; o ângulo de divergência formado entre as CLI é próximo a 90°.

Palavras-chave: Obstrução nasal; Nariz; Cartilagens nasais; Rinoplastia; Respiração

INTRODUCTION

The beauty of the nose is not defined exclusively by measurements but by proportion, balance and harmony with the face1. Among the goals of rhinoplasty are the aesthetic proportions inserted in the context of a functional nose, which improves respiratory quality and is naturally beautiful. This complexity makes rhinoplasty one of the most challenging surgeries within plastic surgery2,3.

Within facial balance, the nose has craniometric points, and these, when correlated, are applied to anthropometry. The relationship of these points to each other determines distances and angles that represent the proportion indices of the face. Among them, the following stand out: glabella (G); radix (R); nasion(N); pronasale (PRN); rhinion (Rh); subnasale (SN); alare (AL); alar curvature point (AC); labrale superius (LS); and gnathion (GN)4.

From the craniometric points of the nose, the craniometric relationships are formed, responsible for defining the nose’s length, width, inclination, and angles. The union of the aforementioned craniometric points will also form the nasofrontal, nasolabial, nasomental and nasofacial angles4,5.

The anatomical conformation of the nose directly influences the arrangement of nasal angles, which is associated with aesthetic and functional characteristics. The face will have proper proportions and symmetry when the points and craniometric relationships are ideal. However, these proportions must be related to good nasal functionality, and the main structures responsible for the function of the nose are the external and internal nasal valves6.

The functional importance of nasal valves was evidenced when Constantian, in 1994, found a 4.9-fold increase in airflow when nasal valve reconstruction was associated with the treatment of septal deviation. However, septoplasty alone increased airflow by only 1.1 times7.

Another relevant data from the author mentioned above was that the isolated reconstruction of the external versus internal nasal valves resulted in an increase in nasal airflow of 2.6 times versus 2.0 times, respectively. Thus, it became evident that the external nasal valve is the most important structure for proper nasal functioning7.

OBJECTIVE

Define the ideal anatomical positioning of the lower lateral cartilages (LLC) associated with optimizing the external nasal valve.

METHOD

The study was carried out through a narrative literature review in the following databases: SciELO, LILACS and Medline. The descriptors used were: “nasal cartilages,”; “nasal obstruction,” and “rhinoplasty,” being selected from 15 essential articles for the understanding of the subject. The review was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo/ Hospital São Paulo (UNIFESP/HSP) and approved under protocol number 5890190419.

This review presents the contextualization between the inferior lateral cartilages and the external nasal valve.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Aesthetics and nasal functionality are directly related to the positioning of the LLC since these anatomical structures are the main structural element of the lateral wall of the external nasal valve8.

The LLCs are formed by the medial, intermediate and lateral cruras, with the domus as the point of greatest projection. The medial crura is the pillar on which the nasal tip rests and is the primary component of the columella. The latter is responsible for the visual correlation of the length of the nostril in the basal view9.

On the other hand, the lateral crura is the main component of the nasal alae, influencing its shape, size and position9. Thus, some situations should always be an alert for diagnosing external valvular nasal insufficiencies, such as boxy tip, bulbous tip, retraction of the nasal alae, deep alar grooves and parenthesis deformity2,5,8,10,11. The malpositioning of the LLC is not only an aesthetic configuration but also reflects on inadequate functionality of the external nasal valve2,8.

It was not until 1994 that the importance of nasal valves in respiratory function was investigated in depth. Many surgeons believed that the air path was defined only by the nasal septum and the inferior nasal turbinates before this date. Therefore, if the patient had a deviated septum and/or inferior turbinate hypertrophy, this was enough to justify nasal respiratory failure7,12.

Breathing involves pressure changes, and the nasal cavity needs to be stable to this variation exerted by inspiration, whether forced or not. The importance of the external nasal valve comes from the fact that it is the first place where airflow encounters resistance10. That is, an external valve dysfunction results in air turbulence with impaired breathing12.

When the patient takes a deep inspiration, physiologically, there must be a dilation of the external nasal valve so that the nasal airflow is laminar and can enter the paranasal sinuses. The cause of the alar collapse or external valve insufficiency during deep inspiration is a low-resistance, hypoplastic or malpositioning LLC10. Anatomical deformities of the lateral crura can also potentially contribute to valve insufficiency6,13.

Constantian, in 1994, was responsible for a pioneering study, showing that when the external nasal valve was reconstructed alone, nasal airflow increased by 2.6 times. In comparison, with septoplasty alone, airflow increased only 1.1-fold. However, when Constantian combined the correction of the external nasal valve, the internal nasal valve and septoplasty, the respiratory flow improved 4.9 times, showing that the external nasal valve alone is responsible for more than half of the nasal airflow7,12.

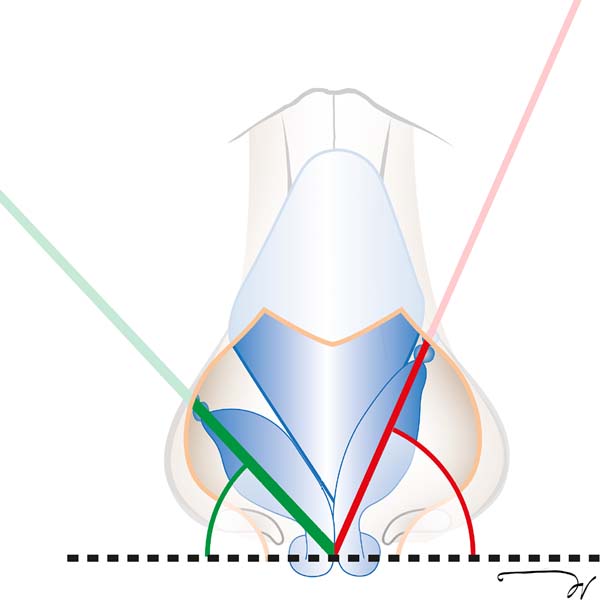

Still, for the same author, it was possible to classify the positioning of the LLC in the preoperative period as adequate or inadequate, based on a straight line drawn between the lateral crura of these cartilages to the patient’s pupil 2,7,14.

When this line projects medially to the pupil, the angle formed between the lateral crura of the LLC and the margin of the nasal alae is greater than 45°, which is considered inadequate. This is because the nasal tip and alae of the nose lack adequate cartilaginous support to maintain the stability of the external nasal valve during inspiration. On the other hand, the positioning of the LLC is considered adequate when the line drawn between the dome and the insertion site of the inferior lateral cartilage in the piriform aperture coincides with the pupil or is lateral to it 2,7,14 (Figure 1).

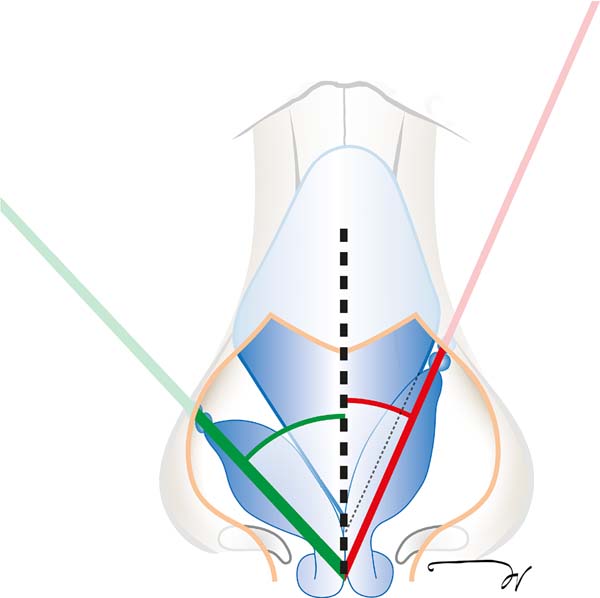

Toriumi & Asher, in their studies, classified the positioning of the LLCs intraoperatively, taking as a reference the angle formed between the lateral crura of this cartilage and the median sagittal plane and used an instrument called a finger goniometer5 for this measurement.

They classified it as inadequate when the angle is equal to or less than 30°, a situation in which the lateral wall of the external nasal valve does not have adequate stability, predisposing to insufficiency of this valve. On the other hand, they considered the angle adequate when it was equal to or greater than 45° 5,13 (Figure 2).

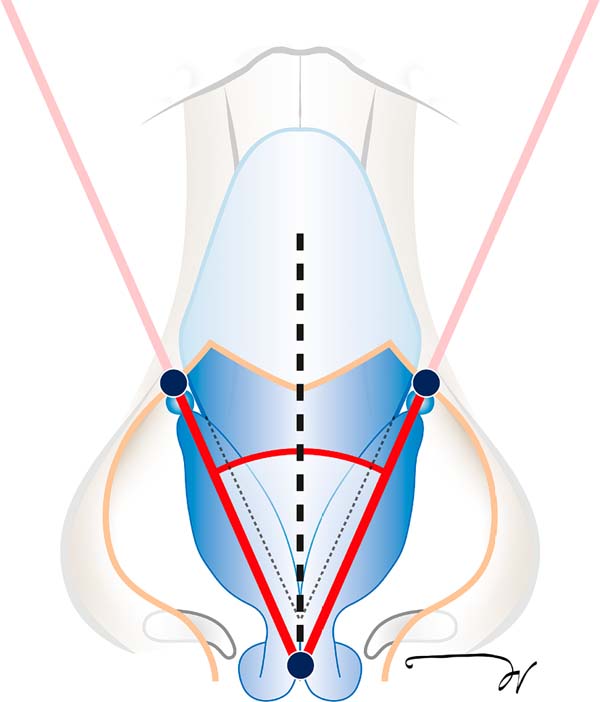

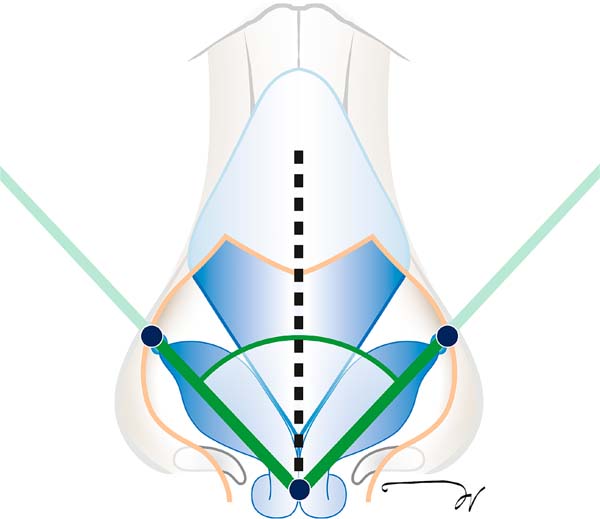

In 2020, Silva improved the Toriumi classification and exposed the concept of the angle of divergence, which is formed between the lateral cruras of the LLC, as a classification parameter for the intraoperative LLC positioning15.

It is important to point out that, in this classification, the author above used the bilateral sum of the angle of the Toriumi classification; that is, the positioning of the LLC was defined as inadequate when the angle of divergence was less than 60° and adequate when the value was equal to or greater than 90° 15 (Figures 3 and 4).

The rhinogoniometer was developed in 2018 to measure the angle of divergence. This device has a patent registration with the National Industrial Property Industry (INPI) under the process number BR 10 2018 073213 7. It is an innovative surgical instrument created specifically for this purpose, allowing the measurement of intraoperative angles with precision, including the divergence angle15 (Figure 5).

The positioning of the LLC is very important because when they are malpositioned, having a divergence angle below 60°, Silva agrees with Toriumi5,13 in carrying out the transposition of these cartilages using the lateral crural strut graft11. Situation in which, if the divergence angle is measured by computerized analysis, the difference between this and the rhinogoniometer is only 0.79°, which does not interfere with the surgeon’s conduct and provides practicality and safety in such a delicate surgical maneuver15.

CONCLUSION

The external nasal valve was associated with better functioning when the lower lateral cartilages are well-positioned and may have three measurements depending on the anatomical references used:

REFERENCES

1. Broer PN, Buonocore S, Morillas A, Liu J, Tanna N, Walker M, et al. Nasal aesthetics: a cross-cultural analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(6):843e-50e. PMID: 23190836 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31826da0c1

2. Constantian MB. The boxy nasal tip, the ball tip, and alar cartilage malposition: variations on a theme--a study in 200 consecutive primary and secondary rhinoplasty patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(1):268-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000169958.83870.E1

3. Bared A, Rashan A, Caughlin BP, Toriumi DM. Lower lateral cartilage repositioning: objective analysis using 3-dimensional imaging. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014;16(4):261-7. PMID: 24722813 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2013.2552

4. Furtado IR. Nasal morphology - harmony and proportion applied to rhinoplasty. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2016;31(4):599-608. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5935/2177-1235.2016RBCP0100

5. Toriumi DM, Asher SA. Lateral crural repositioning for treatment of cephalic malposition. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015;23(1):55-71. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsc.2014.09.004

6. Silva EN, Bittencourt RC. Preoperative and postoperative assessment of external nasal valve in rhinoplasty. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2017;32(1):17-27.

7. Constantian MB. The incompetent external nasal valve: pathophysiology and treatment in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(5):919-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199404001-00004

8. Silva EN. The Relation Between the Lower Lateral Cartilages and the Function of the External Nasal Valve. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(1):175-83. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-018-1195-x

9. Daniel RK. The nasal tip: anatomy and aesthetics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89(2):216-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534199202000-00002

10. Kemaloğlu CA, Altıparmak M. The alar rim flap: a novel technique to manage malpositioned lateral crura. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35(8):920-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjv111

11. Gunter JP, Friedman RM. Lateral crural strut graft: technique and clinical applications in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(4):943-52. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534199704000-00001

12. Constantian MB, Clardy RB. The relative importance of septal and nasal valvular surgery in correcting airway obstruction in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(1):38-54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534199607000-00007

13. Toriumi DM. Discussion of Paper Entitled “The Relation Between the Lower Lateral Cartilages and the Function of the External Nasal Valve.” Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(1):184-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-018-1269-9

14. Constantian MB. The two essential elements for planning tip surgery in primary and secondary rhinoplasty: observations based on review of 100 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6):1571-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000138755.00167.F5

15. Silva EN, Dos Santos TK, Ferreira LM. Rhinogoniometer: Validation of an Instrument for Rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(6):1264-9. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000008587 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000008587

1. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

2. Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Ponta Grossa, PR, Brazil

ENS Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

TKS Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Investigation.

LMF Conception and design study, Final manuscript approval, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author: Eduardo Nascimento Silva Avenida Doutor Francisco Búrzio, 991, Ponta Grossa, PR, Brazil, Zip Code: 84010-200, E-mail: dr_eduardosilva@yahoo.com.br

Article received: July 18, 2020.

Article accepted: March 06, 2022.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter