Review Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 - Issue 2

Principle of non-discrimination and non-stigmatization: considerations for improving the quality of life of people with burn sequelae

Princípio da não discriminação e não estigmatização: ponderações para a melhoria da qualidade de vida de pessoas com sequelas de queimaduras

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The increase in the survival of burn victims brought to reality the problems related to sequelae, which can generate stigmatization and discrimination and influence all aspects of the individual's life. The objective is to analyze the principle of non-stigmatization and non-discrimination of the Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights in improving the quality of life of people with burn sequelae.

Methods: Integrative review using the PICO strategy, P=patient victim of burn sequelae; I=principle of non-stigmatization; C=healthy psychosocial; Result=improvement of quality of life, for the question: How can the application of the principle of nonstigmatization and non-stigmatization help to improve the quality of life of people with burn sequelae?

Results: In the last five years, 77 articles were found with the stigma and burn descriptors, and twelve were selected for analysis. The instruments for assessing stigma, stress, and self-esteem have been described. People who were victims of burn sequelae had a great psychosocial burden, stigmatization, and discrimination that persisted over time.

Conclusion: In this integrative review, instruments were found to assess stigma, stress, self-esteem and assess social support. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors related to stigmatization and discrimination were identified, and considerations and reflections were presented to apply the Principle of non-stigmatization of Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights as proposed by the authors, who highlighted actions that can improve people's social support and quality of life with burns sequelae.

Keywords: Burns; Quality of life; Bioethics; Social stigma; Social discrimination.

RESUMO

Introdução: O aumento na sobrevida de pessoas vítimas de queimaduras trouxe para a realidade os problemas relacionados às sequelas, que podem gerar estigmatização e discriminação e influenciar todos os aspectos da vida do indivíduo. O objetivo é analisar o princípio da não estigmatização e não discriminação da Declaração Universal de Bioética e Direitos Humanos na melhoria da qualidade de vida das pessoas com sequelas de queimaduras.

Métodos: Revisão integrativa pelo uso da estratégia PICO, P=paciente vítima de sequela de queimadura; I=princípio da não estigmatização; C=função psicossocial saudável; Resultado=melhoria da qualidade de vida, pela questão: Como a aplicação do princípio da não estigmatização e não estigmatização pode auxiliar para a melhoria da qualidade de vida de pessoas com sequelas de queimaduras?

Resultados: Nos últimos cinco anos foram encontrados 77 artigos com os descritores stigma and burn, doze foram selecionados para análise. Os instrumentos de avaliação de estigma, estresse, autoestima foram descritos. As pessoas vítimas de sequelas de queimaduras apresentaram grande carga psicossocial, estigmatização e discriminação envolvidas, que persistiram ao longo do tempo.

Conclusão: Nesta revisão integrativa foram verificados instrumentos para avaliação do estigma, estresse, autoestima e avaliação do suporte social. Foram identificados fatores intrínsecos e extrínsecos relacionados a estigmatização e discriminação, e apresentaram-se ponderações e reflexões para a aplicação do princípio da não estigmatização da Declaração Universal de Bioética e Direitos Humanos conforme propostas por autores, que destacaram ações que podem melhorar o suporte social e a qualidade de vida de pessoas com sequelas de queimaduras.

Palavras-chave: Queimaduras; Qualidade de vida; Bioética; Estigma social; Discriminação social

INTRODUCTION

Goffman’s works that led to the writing of “Stigma: Notes on the Handling of Deteriorated Identity”1 had important contributions to the social study of stigmatization. The word stigma has a Greek origin to refer to bodily signs with which it was sought to evidence something extraordinary or evil about the person’s moral status. These signs showed that the bearer was an enslaved person, traitor, or criminal, historically incorporated into the effects of divine grace and physical defects, among others1.

Stigma is a situation of the individual who is unable to accept, with prospects of being discredited fully or discreditable, originating from physical defects; individual (mental, alcoholism, homosexuality, addiction, unemployment, etc.) or tribal (race, nation, religion, etc.) of identity, often being named by the condition, for example, the person with a burn sequelae as “the burnt,” with discrimination in psychosocial contexts.

Unconventional interpretations of greater exposure can lead to extremes of victimization, need for secondary gains, reduction of social exchange by selfisolation, and can become an uncontrolled, depressed, hostile, anxious, confused, aggressive or shy person. Many are sometimes discredited in the face of the unreceptive world1.

Burns are injuries that significantly contribute to increased mortality and disability rates, resulting in at least 265,000 deaths annually. They are among the main causes of disability-adjusted life years in low- and middle-income countries and the main causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide2. Globally, young people between 15 and 44 are responsible for nearly 50% of injury-related deaths worldwide. In fact, 7 of the 15 leading causes of death for people aged 5 to 29 are road traffic injuries, suicide, homicide, war, drowning, poisoning, and burns.

National and international initiatives have been carried out to prevent burns, and the World Health Organization developed 2008 the plan for the prevention and care of burns and, in conjunction with the International Society for Burn Injuries (ISBI), began collecting data from Burn Treatment Centers on burn victims, in the Global Burn Prevention Program. The program will gather information from several countries and will be updated monthly3,4.

The coexistence of people with sequelae and physical deformities caused by burns with those considered “normal” could lead to impaired selfperception, which could generate feelings of selfdepreciation, self-hatred, and low self-esteem. How would the stigmatized person deal with this situation? Mainly, plastic surgery is trying to correct the defect, the object of the stigma. However even after multiple and complex procedures, there would still be evidence of an attempt to correct the defect, especially in the treatment of burn sequelae, as it is difficult or impossible for the plastic surgeon to erase the scars caused by the trauma1-3. The number of publications on subjective and psychosocial aspects involving people with burn sequelae is scarce. Thus, it is important to identify and study this problem, stigma, from a bioethical perspective to protect these individuals.

The Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights5, agreed upon in 2005, is an important tool for promoting better public health policies, contributing to the reflection of the imperative need for its defense in the fight against discrimination and individual stigmatization, and for the strengthening of investments in health systems, as a goal for the millennium development, and psychosocial support in all stages of burns.

The declaration provides in article 11th nondiscrimination and non-stigmatization, in which “No individual or group shall be discriminated against or stigmatized for any reason, which constitutes a violation of human dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms.”5. Godoi & Garrafa consider that stigmatization results in inequalities, power asymmetries and social injustices. Whatever the source of the stigma, the consequences are the same: violation of human dignity, social isolation and exclusion, reduced access to health services, compromised life chances, a deterioration in the quality of life and increased risk of death6.

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the principle of non-stigmatization of the Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights (UDBDH) to improve the quality of life of people with burn sequelae.

METHODS

This is an integrative literature review comprising six steps. In the first stage, the question was formulated according to the PICO strategy, which in evidence-based medicine represents the acronym for “P,” “Patient,” I “Intervention,” “Comparison,” and “Outcomes,” so, Patient: Person suffering from burn sequelae; Intervention: application of the principle of non-stigmatization proposed by DUBDH; Comparison: Healthy psychosocial function; and Outcomes: improvement of quality of life, with the formulation of the question: How can the application of the principle of non-stigmatization, proposed by DUBDH, help to improve the quality of life of people with burn sequelae?

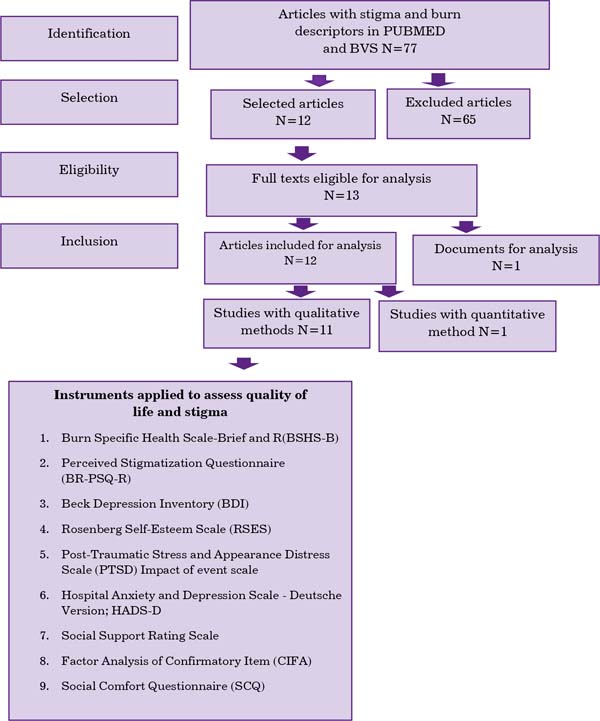

In the second stage, a search was conducted in the PubMed and VHL databases (Virtual Health Library; LILACS, SciELO, PePSIC). Inclusion criteria were studies published in the last 5 years with the descriptors; in any language; complete and abstracts; evaluating the year, study site, study type, sample/ population, intervention, control and outcome. Exclusion criteria: repeated articles; published in sources other than those mentioned in this article; other diseases and procedures. In the third step, the selection of articles, according to the flowchart in Figure 1. In the fourth step, the critical analysis of the included studies; in the fifth, the presentation of the results; and in the sixth, the discussion of these in the light of the Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights5 in its article 11th, non-discrimination, and non-stigmatization.

RESULTS

With the descriptors stigma and burn, 77 articles were found published in the PubMed and VHL databases in the last five years, of which 12 were selected because they met the inclusion criteria shown in the flowchart (Figure 1). Sixty-five studies were excluded according to the exclusion criteria and due to: other causes of mental and psychiatric illnesses, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s; post-traumatic stress from other causes, including among police professionals; stigma in HIV carriers, obesity, transgender, drug users; and also studies of acute and clinical-surgical care with an exclusive presentation of scar revision and techniques for treating burn sequelae in children and an epidemiological study of burns.

Eight articles were found with stigma, burn, and quality of life descriptors. Of these, four were within the inclusion criteria, and the authors Ross et al.7, Gauffin & Öster8, Müller et al.9, and Berg et al.10 have already been listed and presented in Table 1.

| Author/Year/Place | Kind of study | Sample/population/intervention/ control | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jagnoor et al./2018/ Índia2 | Identify priority policy and health system research issues associated with recovery outcomes for burn survivors in India. |

Participants recognized the challenges of burn care and recovery and identified the need for prolonged rehabilitation. |

Strengthening health systems can enable providers to address issues such as development/ delivery, protocols, capacity building, effective coordination, key organizations and referral networks. |

| 2 | Ross et al./2021/EUA7 | Analysis of patient and injury characteristics associated with social stigma by burn survivors from the NIDILRR Burn Model Systems. |

Facial burns and amputations are independent risk factors for social stigma, while

the male gender and greater community integration were protective. |

Importance of counseling for patients who suffer facial burns and/amputations; and

investing in outreach programs for burn survivors to improve social support. |

| 3 | Freitas et al./2019/ Brasil13 |

To compare the perception of stigmatization, symptoms of depression and self-esteem in adults in the general population with burn survivors in Brazil and verify possible correlations between these populations. |

The Brazilian versions of the BR-PSQ-R, BDI and RSES were applied to 120 general population and 240 burn survivors. Moderate correlations were found between the perception of stigmatization and depression and the perception of stigmatization and self-esteem. |

Participants in the general population and burn survivors exhibit similar levels of perceived stigmatization; the general population had fewer symptoms of depression and higher self- esteem when compared to burn survivors. |

| 4 | Gauffin & Öster/2019/Uppsala, Suécia8 | To explore the perception of former burn patients about the specific health of the burn and investigate how these experiences correspond to the subscales of the BSHS-B. | Between 2000 and 2007 - 20 respondents with TBSA >20% between 10 and 17 years after the burn. Despite extensive burns, respondents said they led a nearnormal life. Other topics after the burn were: skin problems, reduced use of morphine, the importance of work, stress, mentality and the health system. | The BSHS-B alone may not be sufficient to assess the long-term self-perception of health of former burn patients. The investigation of supplementary areas that reflect the socio-cultural environment of former patients and personal factors can be of great importance. |

| 5 | Macleod et al./2016/ Nottingham, Inglaterra14 |

Examine how PTSD and the preoccupation with appearance associated with burns are experienced when both difficulties occur. |

Interpretive phenomenological analysis of 8 women with PTSD symptoms, it was observed

the concern with the appearance and the maintenance of the threat sensation through the social stigma acts as a trigger to relive the traumatic incident that caused the burn. |

The results suggest that psychosocial interventions need to be adapted to address processes related to concerns about change in appearance and traumatic reliving. |

| 6 | Barnett et al./2017/Malawi15 | Record findings from a support group in Malawi and provide qualitative analysis of content discussed by burn survivors and caregivers | Caregivers discussed issues of guilt and self-reproach for their children's injuries; emotional distance between caregiver and survivor, fears about the patient's probable death, and concerns about the future and stigma associated with burns | Establishment of a support group in the burn unit provided space for burn survivors and their families to discuss subjective experiences and coping techniques. |

| 7 | Berg et al./2017/ Alemanha10 | To analyze whether patients at different periods since the burn differed in psychosocial impairment. |

Between 2006 and 2012, BSHS-B, HADS-D, PTSD, IES-R, PSQ and SCQ were asked about the quality of life. |

The results suggest persistence of the psychosocial burden over time after a burn.

Psychosocial interventions may be indicated even many years after burns. |

| 8 | Roberson et al./2020/ Multicêntrico16 | Multicenter study on tissue banks in low- and middle-income countries. | Three thousand three hundred forty-six records and 33 reports from 17 countries were analyzed, and obstacles to bank creation were found: high capital costs and operating costs per graft; insufficient training opportunities; deregistration of donation and socio-cultural stigma around transplant donation. |

The availability of skin allografts can be improved by strategic investments in governance and regulatory frameworks; international cooperation initiatives; training programs; standardized protocols, and inclusive public awareness campaigns; Capacity-building efforts that involve key stakeholders can increase donation and transplant rates. |

| 9 | Freitas et al./2018/ Brasil17 |

Validity of the Portuguese PSP version developed in the USA for burn patients. |

240 adult burn patients admitted to rehabilitation in two burn units in Brazil. PSQ scores were correlated with BDI, RSE, and two BSHS-R domains: affect and body image and interpersonal relationships. Confirmatory Item Factor Analysis (CIFA) was used to test the three factors (absence of friendly, confused, and hostile behavior) |

PSQ-R scores correlated strongly with depression, self-esteem, body image, and interpersonal relationships. Total PSQ-R scores were significantly lower for patients with visible scars. The PSQ-R showed reliability and validity comparable to the original version |

| 10 | Ren et al./2018/China11 | Explore and conceptualize the obstacles encountered in providing mental health care to burn patients. |

Interview 16 burn patients, five nurses, four rehabilitation the- rapies, five physicians and eight caregivers about their experiences with current health services and barriers. |

Need to focus on the underlying social, economic, and cultural determinants of mental health care. |

| 11 | Müller et al./2016/ Alemanha9 |

Validity of the German version of the PSQ/ SCQ in burn victims. |

All PSQ/SCQ scales showed good internal consistency. Higher PSQ means/lower SCQ means were related to less social support, lower quality of life, and more symptoms of anxiety/depression. |

A four-factor structure and good validity of the PSQ/SCQ were evidenced. Further studies should investigate the application of the PSQ/SCQ in individuals with appearance differences unrelated to burns. |

| 12 | Borges et al./2018/ Brasil12 |

Identify the relationship between spirituality and religiosity in women's empowerment burned by self-immolation. |

Method of “narrative of the disease” with support in women's speeches. | The burn victim woman showed multiple nuances concerning self-image and self-esteem. Faith in religion and spirituality helped in overcoming personal and social conflicts. |

NIDILRR - National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research; BR-PSQ-R - Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire (BR-PSQ-R); BDI - Beck Depression Inventory; RSES - Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; BSHS-B - Burn Specific Health Scale-Brief; PTSD -post-traumatic stress disorder; TBSA -Total body surface area; HADS-D - anxiety and depression scale; IES-R - Impact of Event Scale-Revised; SCQ - Social Comfort Questionnaire.

The search was expanded in reference journals in Brazil, including the Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (RBCP) and the Revista Brasileira de Queimaduras. In the last five years, 33 articles were published in the first, and 10 on quality of life and burns in the second, but they did not present the descriptor stigma and inclusion criteria.

In the VHL database (SciELO, LILACS and PePSIC), five articles were found with the descriptors “stigma and burn,” four of which were already included, namely Gauffin & Öster8, Ren et al.11, Berg et al.10, Müller et al.9, and one by Borges et al.12, who studied the relationship of spirituality and religiosity in the empowerment of women burned by self-immolation. The results are shown in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

The assessment of non-stigmatization can serve as an indicator of the quality of life for people with burn sequelae, with the definition of the sequel as a permanent anatomical or functional change caused by the burn; some authors preferred to name as expatients and survivors. Considering the definition of health indicators as instruments used to measure reality, as a guiding parameter, an instrument for management, evaluation and planning of health actions, to allow changes in the processes and results of the actions proposed in a strategic planning18.

The authors surveyed in this review used a qualitative methodology to assess stigma in burn victims, using instruments already validated or with the objective of validation in their countries. For better understanding, the discussion was divided into the following topics:

Assessment instruments

The Burn Specific Health Scale-Brief (BSHS-B), used by two studies10,17, is a specific and multidimensional instrument that addresses various aspects of outcomes and rehabilitation in the treatment of burn victims, with 114 items. It has three modalities, the Burn Specific

Health Scale-Abbreviated (BSHS-A), consisting of 80 items, and the Burn Specific Health Scale-Revised (BSHS-R), translated into Portuguese and validated by Ferreira (apud Piccolo19), comprising 31 items and six domains: the ability for simple function, work, treatment, affection and body image, interpersonal relationships, and sensitivity to heat. However, this instrument modality did not address hand function and sexuality aspects. It is the specific instrument most used worldwide for this purpose, it was translated into Portuguese and adapted and validated for Brazil and called BSHS-B-Br19.

The Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire (BR-PSQ-R) and the Social Comfort Questionnaire (SCQ) were developed in the USA to measure the perception of stigmatizing behaviors directed at individuals with changes in appearance and assess the social comfort of these individuals. It has shown good validity among people who have suffered burns and was used by four of the authors surveyed. These publications showed validation studies by Brazilian and German authors9,10,13,17.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a selfadministered instrument composed of 21 items whose objective is to measure the intensity of depression from 13 years old to old age. The application can be individual or collective. Another scale to assess depression was the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - Deutsche Version; HADS-D10.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) is widely used in general. Originally in English by Morris Rosenberg in 1965, it was developed as a global selfesteem assessment scale, applied to 5,024 individuals, including university students and seniors in New York. Self-esteem affects many behaviors, with evidence showing associations between low self-esteem and negative mood, perception of disability, delinquency, depression, social anxiety, eating disorders and suicidal ideation and the association between high self-esteem and mental health, social skills and well-being17.

The post-traumatic stress and appearance distress (PTSD) scale assesses living with a traumatic stressor, such as a burn. It was used in two studies10,14 to assess burn victims. Another instrument used was the Impact of Event Scale. The Impact of Event Scale (IES) assesses subjective stress related to life events, not focusing on a specific situation but on the particular characteristics that involve such events. It is composed of only 15 items, configured as a four-point Likert scale, self-administered, fast and low-cost with good psychometric parameters, with the possibility of use in clinical practice and research, and the social support assessment scale. The social support assessment scale assesses the influence of social interactions on people’s well-being and health; being important for understanding how the lack or precariousness of social support could increase vulnerability to diseases and how to support social protection would protect individuals from damage to physical and mental health resulting from stressful situations20,21.

Social stigma and psychosocial impairment

In the interview conducted by Ren et al.11 with 16 burn patients, five nurses, four rehabilitation therapists, five physicians and eight caregivers about their experiences with current health services and barriers, it was identified that beliefs, knowledge, socioeconomic status, cultural understanding of people’s mental health and social stigma appear to play important roles in the public health approach to health promotion and post-burn psychosocial interventions. Freitas et al.13,17 compared the perception of stigmatization, symptoms of depression and self-esteem in adults from the general population with burn survivors in Brazil, verified the possible correlations between these populations, and extended the validation of the PSQ questionnaire to the Brazilian reality.

Corroborating the authors’ findings mentioned above, the study by Ross et al.7 considered facial burns and amputations as independent risk factors for experiencing social stigma. Berg et al.10 highlighted that the research results regarding the different periods since the burn did not differ concerning psychosocial impairment, verifying that they suggest the persistence of the psychosocial burden related to the sequelae of burns over time. It is also worth mentioning that there were no significant differences in psychosocial suffering regarding sociodemographic and burn-specific variables; 18 (12.4%) patients had a cutoff point >11 for anxiety and 22 (15.2%) for depression; 16 (11.1%) patients screened positive for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). No difference was found for current (drug) psychotherapy and desire for psychotherapy.6

As explained by all the authors of this review, psychological disorders were prevalent and psychosocial interventions can be indicated even after many years in people with burns; however, psychological services are rarely accessible for post-burn injuries, as reported by Ren et al.11 and Barnett et al.15, in which burn survivors discussed frustration with long courses of hospitalization, hope created through interactions with hospital staff, the association between mental and physical health, about their injuries and how it would affect their future, decreased self-worth, increased focus on their own mortality and family, and interpersonal difficulties.

Borges et al.12 proposed a narrative study to identify the relationship between spirituality and religiosity in women’s empowerment burned by self-immolation. They observed that women with hypertrophic scars presented different reactions and, with their speeches, the categories of religion emerged as the high point of salvation, stigmatization and the victim’s response to society’s rejection, non-acceptance of the new body image, self-rejection, self-prejudice and spirituality in the process of empowerment of burned women.

The study by Jagnoor et al.2 revealed that participants, healthcare providers, burn survivors, caregivers, neighbors/community, non-governmental organizations involved in rehabilitation, legal assistance, workplaces and key health personnel in implementing service recognized the challenges of burn care and recovery and identified the need for prolonged rehabilitation.

Challenges identified included poor communication between health providers and survivors, limited rehabilitation services, difficulties with transportation to the health facility, and high costs associated with treating burns. Both burn survivors and healthcare professionals identified the stigma associated with burns as the greatest challenge within the healthcare system and the community. System barriers (e.g., limited infrastructure and human resources), lack of economic and social support and poor understanding of recovery and rehabilitation have been identified as the main barriers to recovery2.

Analysis of the principle of non-discrimination and non-stigmatization of the UDBDH in improving the quality of life of people with burn sequelae

In today’s society, the term stigma expresses something bad, something that should be avoided, and that expresses a deteriorated identity1, which results from the production and mimesis of unequal power relations; it is conservative, feeding the unjust social order and disrespecting different identities, while human dignity concerns the fact that dignity is an intrinsic attribute of the human person and, consequently, is inalienable, inalienable and unavailable5.

Discrimination is any distinction, exclusion or restriction of preference based, among other things, on physical disability or other characteristics not relevant to the matter at hand. In this review, no instruments were applied to assess discrimination, which was described by the researchers indirectly through the perception of stigmatization. Other instruments, such as the Experiences of Discrimination (EOD)22, could be applied to this population in future studies.

Whether individual or in groups, the process of identity construction is a social construction linked to intersubjectivity1; that is, human dignity presupposes respect for the other, human plurality and diversity. Through the human condition, we are equal, but at the same time, we are singular, but these differences cannot cause inequalities and discrimination23.

Because of what was exposed by the authors of this integrative review, at this stage, we sought to analyze, in the light of bioethics, how the DUBDH document in article 11th of the principle of nondiscrimination and non-stigmatization can contribute to improving the quality of life of people with sequelae of burns.

This document was validated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) after ratifying the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights in 2005 (UDBDH)5. Its foundation is justice, recognition of the dignity of the human person, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. From article 11th of the declaration, any discriminatory or stigmatizing act that causes inferiority to the individual and the withdrawal of his dignity becomes unacceptable, thus reiterating the need to seek tools for coping for people in these conditions.

Following the line of non-stigmatization and measures for coping and changes, this research listed authors Jagnoor et al.2, Ren et al.11 and Roberson et al.16, among others. Ren et al.11 observed that participants recognized the challenges of burn care and recovery with the need for prolonged rehabilitation. Challenges identified included poor communication between health providers and survivors, limited rehabilitation services, difficulties with transportation to the health facility, and high costs associated with treating burns.

Both burn survivors and healthcare professionals identified the stigma associated with burns as the greatest challenge within the healthcare system and the community. System barriers (e.g., limited infrastructure and human resources), lack of economic and social support, and poor understanding of recovery and rehabilitation have been identified as major obstacles to recovery2.

Roberson et al.16, based on the experience that wound excision and temporary coverage with a biological dressing, such as an allograft, can improve the survival of patients with major burns, carried out a study evaluating the health systems in low- and middleincome countries (LMICs), which rarely have access to allografts. This fact may contribute to the limited survival of patients with major burns at these sites.

A study was carried out on the implementation and maintenance of tissue banks in LMICs to guide the planning and organization of the system. The survey consisted of 3346 records, with 33 reports from 17 countries. Commonly reported barriers to implementation, ideal or planned, include high capital costs and operating costs per graft, insufficient training opportunities, donation schemes, and socio-cultural stigma around donation and transplantation. It was highlighted that the availability of skin allografts could be improved through strategic investments in governance and regulatory frameworks, international cooperation initiatives, training programs, standardized protocols, capacity building and inclusive public awareness campaigns16.

Furthermore, Ross et al.7 highlighted the importance of counseling for patients who suffer facial burns and/or amputations; and the need to invest in outreach programs for burn survivors to improve social support.

CONCLUSION

The results obtained in this integrative review about stigma in patients with burn sequelae presented instruments for assessing stigma, stress, self-esteem and assessment of social support. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors related to stigmatization were identified, and considerations were presented on the principle of nondiscrimination and non-stigmatization of UDBHR as proposed by the authors, who highlighted actions that can improve social support and the quality of life of people with sequelae of burns.

This study brought to reflections the human singularity, that is, how the quality of being unique, distinct from others, important in the formation of the self, is established in the social relationship with other beings, through alterity, the look of the other and for the other, allowing us to see and perceive the other and ourselves. The reduction of individuality derived from stigmatization can reach the limit of dehumanizing the stigmatized person and discriminating against him/her to the point that the individual’s identity is determined by the stigma itself or is confused with it, increasing the vulnerability of individuals and groups23.

In the specific case of patients with burn sequelae, the Declaration is extremely valuable because it includes social, psychological, and economic issues involved in the genesis of the injury in the bioethical agenda. Through DUBDH, we will promote reflections on empowerment and, consequently, awareness of the need for social participation of individuals affected by burns, thus ratifying the patient’s autonomy.

REFERENCES

1. Goffman E. Estigma: notas sobre a manipulação da identidade deteriorada. 4ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: LTC; 2008.

2. Jagnoor J, Bekker S, Chamania S, Potokar T, Ivers R. Identifying priority policy issues and health system research questions associated with recovery outcomes for burns survivors in India: a qualitative inquiry. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020045. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020045

3. Hundeshagen G, Wurzer P, Forbes AA, Cambiaso-Daniel J, Nunez-Lopez O, Branski LK, et al. Burn prevention in the face of global wealth inequality. Saf Health. 2016;2(5):1-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40886-016-0016-7

4. Nações Unidas Brasil. Desenvolvimento sustentável do milênio. Saúde e Bem-Estar. [Internet]. Brasília: Nações Unidas Brasil [acesso 2021 Maio 10]. Disponível em: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/sdgs/3

5. Declaração de Bioética e Direitos Humanos [Internet]. [acesso 2021 Maio 10]. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/declaracao_univ_bioetica_dir_hum.pdf

6. Godoi AMM, Garrafa V. Leitura bioética do princípio de não discriminação e 8. Não estigmatização. Saúde Soc. 2014;23(1):157-66.

7. Ross E, Crijns TJ, Ring D, Coopwood B. Social factors and injury characteristics associated with the development of perceived injury stigma among burn survivors. Burns. 2021;47(3):692-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2020.07.022

8. de Oliveira Freitas N, Pitta NC, Dantas RAS, Farina JA Jr, Rossi LA. Comparison of the perceived stigmatization measures between the general population and burn survivors in Brazil. Burns. 2020;46(2):416-22. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2019.07.035

9. Gauffin E, Öster C. Patient perception of long-term burn-specific health and congruence with the Burn Specific Health Scale-Brief. Burns. 2019;45(8):1833-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.12.015

10. Macleod R, Shepherd L, Thompson AR. Posttraumatic stress symptomatology and appearance distress following burn injury: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health Psychol. 2016;35(11):1197-204. DOI: 10.1037/hea0000391

11. Barnett BS, Mulenga M, Kiser MM, Charles AG. Qualitative analysis of a psychological supportive counseling group for burn survivors and families in Malawi. Burns. 2017;43(3):602-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.09.027

12. Berg L, Meyer S, Ipaktchi R, Vogt PM, Müller A, de Zwaan M. Psychosocial Distress at Different Time Intervals after Burn Injury. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2017;67(6):231-9. DOI: 10.1055/s-0042-111006

13. Roberson JL, Pham J, Shen J, Stewart K, Hoyte-Williams PE, Mehta K, et al. Lessons Learned From Implementation and Management of Skin Allograft Banking Programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. J Burn Care Res. 2020;41(6):1271-8. DOI: 10.1093/jbcr/iraa093

14. Freitas NO, Forero CG, Caltran MP, Alonso J, Dantas RAS, Piccolo MS, et al. Validation of the Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire for Brazilian adult burn patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190747. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190747

15. Ren Z, Zhang P, Wang H, Wang H. Qualitative research investigating the mental health care service gap in Chinese burn injury patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):902. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-3724-3

16. Müller A, Smits D, Claes L, Jasper S, Berg L, Ipaktchi R, et al. Validation of the German version of the Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire/Social Comfort Questionnaire in adult burn survivors. Burns. 2016;42(4):790-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.01.001

17. Borges RT, Lira CS, Silva RM, Gonçalves JL, Pena PFA. O empoderamento da mulher queimada por autoimolação e sua sustentação na religião e espiritualidade. Rev Bras Promoç Saúde. 2018;31(4):1-7.

18. Franco JLF. Indicadores de Saúde. In: Franco JLF. Sistema de Informação. [Internet]. [acesso 2021 Maio 11]. Disponível em: https://www.unasus.unifesp.br/biblioteca_virtual/pab/6/unidades_conteudos/unidade08/p_03.html

19. Piccolo MS. Burn Specific Health Scale-Brief: Tradução para a língua portuguesa, adaptação cultural e validação [Tese de doutorado]. São Paulo: Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo; 2015. 177 p.

20. Cassel J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104(2):107-23.

21. Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med. 1976;38(5):300-14.

22. Fattore GL, Teles CA, Santos DN, Santos LM, Reichenheim ME, Barreto ML. Validade de constructo da escala Experiences of Discrimination em uma população brasileira. Cad Saúde Pública (Rio de Janeiro). 2016;32(4):e00102415.

23. Levantezi M, Shimizu HE, Garrafa V. Princípio da não discriminação e não estigmatização: reflexões sobre hanseníase. Rev Bioét. 2020;28(1):17-23.

1. Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil

2. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Corresponding author: Katia Torres Batista Asa Norte, Brasília, DF, Brazil, Zip Code: 70910-900, E-mail: katiatb@terra.com.br

Article received: May 13, 2021.

Article accepted: July 14, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter