Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Breast silicone explant: a multicenter longitudinal study

Explante de silicone mamário: um estudo longitudinal multicêntrico

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Following silicone breast implant placement, some patients present symptoms described as breast implant illness and seek explant surgery. This study aims to analyze the historical symptoms and ascertain breast explant patients' impressions at three different times: before breast implant placement while having the implants, and after the explant surgery.

Methods: This survey was designed as a multicenter longitudinal observational study using an online voluntary participation questionnaire sent by e-mail.

Results: 156 patients were analyzed, 84% had three or more symptoms, and 66.1% improved their symptoms after the explant (p<0.001). Before the placement of silicone, the median self-body satisfaction was 7, while with the implants, the median became 9, and after the explant surgery, the median remained up to 9 (p<0.001). Support groups on social networks helped in the decision to explant in 87.2% of the patients.

Conclusion: Patients presenting symptoms after silicone placement show improvement with breast implant removal. Body self-satisfaction increases with the placement of breast implants and remains increased after their removal. Patients who undergo the explant surgery usually regret having implanted silicone; they are very satisfied with the decision to remove them and equally satisfied with the result of the breast explant surgery. Support groups on social networks were important in the decision-making of these patients.

Keywords: Silicone gels; Breast implants; Silicone elastomers; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Breast.

RESUMO

Introdução: Após a colocação de implantes mamários de silicone, algumas pacientes apresentam sintomas descritos como doença do implante mamário e buscam a cirurgia de explante. O objetivo deste estudo é analisar o histórico de sintomas e verificar as impressões dos pacientes submetidos ao explante mamário em três momentos distintos: antes de colocar os implantes mamários, enquanto estavam com os implantes e após a cirurgia de explante.

Métodos: Essa pesquisa foi delineada como um estudo observacional longitudinal multicêntrico utilizando um questionário on-line de participação voluntária enviado por e-mail.

Resultados: Foram analisados 156 pacientes, 84% apresentavam três ou mais sintomas e 66,1% destes obtiveram melhora de sua sintomatologia após o explante (p<0,001). Antes da colocação de silicone, a mediana de autossatisfação corporal era de 7, enquanto estavam com os implantes a mediana tornou-se 9 e após a cirurgia de explante a mediana se manteve em 9 (p<0,001). Grupos de apoio em redes sociais auxiliaram na decisão de fazer o explante em 87,2% das pacientes.

Conclusão: Pacientes que têm sintomas após colocarem silicone apresentam melhora com a retirada dos implantes mamários. A autossatisfação corporal aumenta com a colocação de implantes mamários e permanece elevada após a retirada destes. Pacientes que fazem a cirurgia do explante costumam estar arrependidas de terem colocado silicone, muito satisfeitas com a decisão de removêlos e igualmente satisfeitas com o resultado da cirurgia de explante mamário. Grupos de apoio em redes sociais foram importantes na tomada de decisão destas pacientes.

Palavras-chave: Géis de silicone; Implantes de mama; Elastômeros de silicone; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Mama

INTRODUCTION

The positive impact on patients’ quality of life undergoing the placement of breast implants, especially in augmentation mastoplasty, is well known, knowing its risks and limits1. Statistical data published by the International Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS) indicate that 211,287 breast augmentation operations with silicone implants were performed in Brazil in 2019. According to the 2018 census of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (in portuguese Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica - SBCP), breast augmentation is the most performed cosmetic surgery in Brazil, corresponding to 18.8% of all plastic surgeries2,3. Like Brazilian data, the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) reported 280,692 breast implant surgeries in 20194. Currently, the estimated prevalence of women with silicone breast implants worldwide is 50 million.5

There was not, there is not, and there will not be a silicone breast implant with infinite durability unless the biological reaction of a foreign body is altered6. Some patients need to have their breasts reoperated due to capsular contracture, rupture of the implant or the desire to change the implanted volume, and scientifically the indication of these new surgeries is a consensus7. Silicone is not considered an inert material since several immunological effects have been usually reported to the possible migration of the silicone gel through the rupture of the elastomer or even with its membrane intact - the so-called bleed gel8.

Breast implant disease (BII) is a condition in which a wide variety of systemic symptoms are self-reported by patients. The pathogenesis of this constellation of symptoms and diagnostic criteria remains an object of study and, despite not yet being registered in the International Code of Diseases, it is the subject of research by the U.S. regulatory agency (FDA)9. In an increasing number of cases, patients have chosen to have their implants removed in an effort to treat these symptoms10.

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) statistics, in the United States of America, in recent years, there have been about 20,000 explants per year related to breast reconstruction and around 30,000 explants related to aesthetic breast surgery11. There is no doubt that the patient has the autonomy to define what will remain in their body; however, there is a lack of evidence about the impact of implant removal on patients’ symptoms for evidencebased medical advice to occur.

OBJECTIVE

This study aims to analyze the history of symptoms and verify the impressions of patients who underwent breast explant surgery at three different times: before placing the breast implants, while they had the implants and after the explant surgery.

METHODS

This research was designed as a multicenter longitudinal observational study using a voluntary participation questionnaire. This research protocol was approved by the National Council of Ethics in Research and is registered under the number 40784420.8.0000.5336.

Patients operated on by researchers working in five different hospitals were invited to participate in the study through an e-mail sent in March 2021. This invitation included the Informed Consent Form and the questionnaire with six sections for self-completion of voluntary participation, which contained direct questions, multiple-choice questions, and numerical scales of body satisfaction (zero corresponding to total dissatisfaction and ten to total satisfaction)12 using Google Workspaces (Google Inc., California, USA).

Inclusion criteria were breast explant surgery performed with one of the research physicians between January 2010 and September 2020 and age between 21 and 69 years until the explant surgery. Exclusion criteria were vulnerable populations, surgery to place a new breast implant after explant and users of illicit drugs.

The data obtained were exported to the IBM SPSS v. 20.0 (IBM, New York, USA) for statistical analysis. Frequencies and percentages described categorical variables. The Kolmogorov Smirnov test verified the symmetry of the variables. Quantitative variables with normal distribution were described by the mean and standard deviation and those with non-normal distribution by the median and the interquartile range. Symptoms were compared between the times evaluated by the McNemar test. The body self-satisfaction scale was compared between times using the Friedman test. To compare body self-satisfaction between patients who underwent mastopexy or fat grafting together with the explant and those who only underwent the explant, the Mann Whitney test was used. A significance level of 5% was considered, represented by p<0.05.

RESULTS

The invitation to participate in the study was sent to 283 patients, and 174 responses were received. After removing incomplete questionnaires, the total was 156 patients (55.1% of those sent). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants who responded to the survey. The mean age when the first implant was placed was 27 years and the median time, they remained with the silicone was 10.5 years. 24.3% of the patients had at least one implant replacement surgery.

| Characteristics | Descriptive measures |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) Female | 155 (99.4) |

| Cisgender | 1 (0.6) |

| Current age (years), mean±SD | 39.5±8.7 |

| Age at first silicone placement (years), mean±SD |

27.0±7.0 |

| Age at explant (years), mean±SD | 38.2±8.7 |

| White skin color, n (%) | 133 (85.8) |

| Current Body Mass Index (cm|kg2), mean±SD | 23.05±3.09 |

SD: Standard deviation.

Table 2 shows the relationship between silicone implants and patients’ symptoms. 91.7% of patients had at least one symptom of BII while on silicone. All BII symptoms had a statistically significant increase comparing the moments before implantation and while with the implants. After explant, there was a significant decrease in all BII symptoms, except for the relapsing fever. Only two symptoms did not return, with statistical significance, the frequency before implantation, dry mouth (p=0.065) and irritable bowel syndrome (p=0.096).

| Symptoms | Before implant | During Implant | After explant | p Before During | p During After | p Before After |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before After | 1 (0.6) | 100 (64.1) | 26 (16.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | - | 24 (15.4) | 7 (4.5) | - | - | |

| Arthralgia | 5 (3.2) | 69 (44.2) | 26 (16.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chronic fatigue | 5 (3.2) | 95 (60.9) | 15 (9.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.031 |

| Difficulty sleeping | 8 (5.1) | 94 (60.3) | 21 (13.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Insufficient sleep | 9 (5.8) | 100 (64.1) | 26 (16.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Neurological manifestations associated with demyelination | - | 11 (7.1) | 2 (1.3) | - | 0.004 | - |

| Reasoning difficulties | 3 (1.9) | 89 (57.1) | 13 (8.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.013 |

| Memory loss | 3 (1.9) | 90 (57.7) | 17 (10.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Recurrent fever | - | 7 (4.5) | 3 (1.9) | - | 0.125 | - |

| Dry mouth | 2 (1.3) | 80 (51.3) | 9 (5.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.065 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 8 (5.1) | 55 (35.3) | 16 (10.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.096 |

| Loss of hair | 9 (5.8) | 106 (67.9) | 29 (18.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sclerosis | - | 1 (0.6) | - | - | - | - |

Data presented by n (%) and compared between times using the Mac Nemar test. If there are no patients in the category, the test is not calculated.

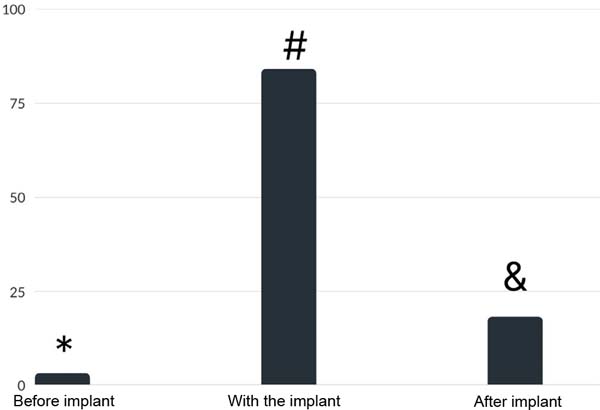

Figure 1 shows that, before placing the implant, 2.6% of the patients had at least three symptoms; while they were with the implants, they became 84.0%, and after removal, 17.9% of the patients remained with three or more symptoms; there was a significant difference between before and during the use of implants (p<0.001), during and after (p<0.001) and before and after (p<0.001). 84% of the patients had three or more symptoms of BII, and 66.1% of them had an improvement in their symptoms after explant (Figure 1).

Table 3 shows that we did not find changes in the frequencies observed concerning cancer, diabetes, epilepsy, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, HIV, hepatitis, hypertension, Chron’s disease, or nephropathies before implantation of silicone and after explant. When analyzing autoimmune diseases, 9.7% of the patients had an autoimmune disease before, 35.3% while they had the implants and 23.2% after the explant; there was a significant difference between before and with silicone (p<0.001), with silicone and after explant (p<0.001) and before and after implantation (p=0.001).

| Symptoms | Before implant | During Implant | After explant | p Before During | p During After | p Before After |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | - | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | - | 0.500 | - |

| Epilepsy | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cancer | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3)) | 1 (0.6) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Hypothyroidism | 7 (4.5) | 31 (19.9) | 27 (17.3) | <0.001 | 0.344 | <0.001 |

| Venous thrombosis | - | 2 (1.3) | - | - | - | - |

| Pulmonary embolism | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| HIV | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hepatitis | 1 (0.6) | - | - | - | - | - |

| High pressure | - | 6 (3.8) | 2 (1.3) | - | 0.125 | - |

| Chron’s Disease | 1 (0.6) | 5 (3.2) | 5 (3.2) | 0.219 | 1.000 | 0.125 |

| Asthma | 10 (6.4) | 4 (2.6) | 3 (1.9) | 0.109 | 1.000 | 0.039 |

| Kidney disease | - | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | - | 1.000 | - |

| Skin disease | 8(5.1) | 48 (30.8) | 13 (8.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.267 |

Data presented by n (%) and compared between times using the Mac Nemar test. If there are no patients in the category, the test was not calculated.

Table 4 illustrates patients’ impressions of body appearance. Before silicone placement, the median body self-satisfaction was 7; while they had the implants, the median became 9, and after the explant surgery, the median remained at 9. Patients’ satisfaction with their body before placement was significantly lower than satisfaction while with the implants (p<0.001) and after the explant (p<0.001); there was no difference in the patients’ aesthetic satisfaction while they were on the silicone and after the explant.

| Before putting | While they were implanted | After explant | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body self-satisfaction, 7 (5 to 8)a median (IQR) | 9 (8 a 9)b | 9 (8 a 9)b | <0.001 |

Friedman test; IQR=interquartile range;

a,b Different letters represent different distributions.

The median of patients who underwent mastopexy concerning satisfaction with their body was 9 (interquartile range from 8 to 10), and in those who did not, the median was also 9 (interquartile range from 8 to 10), with no statistically significant difference. (p=0.220). The median of patients who underwent fat grafting was 9 (interquartile range from 8 to 10), and in those who did not, the median was also 9 (interquartile range from 8 to 10), with no statistically significant difference between performing only the explant or associating with mastopexy or fat grafting (p=0.186). Of the patients evaluated, 1.3% would think about having silicone implants again, 6.4% would recommend that a friend have silicone implants, and 97.4% would advise that a friend perform the explant.

Of the patients evaluated, 83.3% reported regret having had the implant surgery, while 0.6% regretted having had the explant surgery. The physician’s advice who placed the silicone helped in the decision to perform the explant in 32.9% of the patients, while support groups on social networks helped in the decision of 87.2% and news in newspapers, magazines or websites contributed to the decision of 46.5%.

DISCUSSION

An emerging reality that Plastic Surgery faces is the concern of patients that their silicone implants are the cause of symptoms referred to by the term BII, or even that, even without symptoms, they could develop diseases over time. Patients’ complaints about BII should be taken seriously, and symptomatic patients may choose to have the implant removed, informed that the explant will not necessarily be curative for any systemic symptoms13. Our study showed that breast explant surgery has a significant reduction rate in some BII symptoms.

Peters et al., in 1997, when studying 100 consecutive breast explant patients, observed that the motivation for explant in 76% of cases was due to suspected health problems related to silicone14. Our research showed similar results since the main reasons for explant were symptoms of BII (26.9%), aesthetics (26.3%), diagnosis of an autoimmune disease (16.0%) and Adjuvant-Induced Autoimmune Syndrome (ASIA) (16.0%).

A widely accepted theory proposes an adjuvant effect of silicone in developing autoimmune diseases in genetically predisposed patients. However, the wide range of symptoms in patients who develop these pathologies raises doubts about the relationship between the silicone implant’s adjuvant effects with a specific autoimmune disease or a mixture of these diseases15. The lack of consensus on this topic leaves an important gap in current knowledge; however, the significant number of 16% of patients in our study opting for implant removal after having the medical diagnosis of ASIA syndrome draws attention.

In the 1994 Baylor College cohort, 100 patients diagnosed with adjuvant breast disease after silicone breast implants or silicone injections were studied16. This set of symptoms described in 1994 is identical to those currently referred to as BII. In this study, 96 patients underwent breast explant, and the mean age of patients at the explant was 44 years. Graf et al., in 2019, studying 26 patients who wanted to remove silicone implants, most of them because they wanted smaller breasts without implants, observed a mean age of 59 years17. Our study found a younger population with a mean age of 38 years at explant.

Maijers et al., in 2013, studying 52 patients undergoing breast explant, observed a significant reduction in BII symptoms in 69% of them18. These data agree with our study, which found a 66.1% reduction in patients with three or more symptoms of BII. de Boer et al., in 2017, demonstrated that the explant is useful for improving silicone-related complaints in 75% of patients, whereas, in patients who developed autoimmune diseases, improvement is only observed when the explant is combined with immunosuppressive therapy19.

Even so, we do not know all the triggers of autoimmune diseases, including regard to each patient’s individual and unique issues, with the adjuvant being one of the reasons for the development of the disease. Performing the explant would be an attempt to remove the trigger that keeps the autoimmune disease in activity or that could activate other autoimmune bases, generating new diseases. Several patients have, in addition to breast implants, intrauterine devices, fillers, tattoos, and dental implants, and all of these may be responsible for both the initial trigger and the maintenance of the disease. There is no way to define which one was the precursor.

The 2017 Maastricht cohort study consisted of 100 patients diagnosed with ASIA syndrome after placing silicone breast implants; 54 of these patients underwent explant surgery20. Of these, 50% showed improvement in ASIA syndrome symptoms after explant. However, improvement was observed only temporarily in seven patients, with recurrence of complaints after a few weeks. Our study proved compatible, as we found a 66.1% improvement in BII symptoms.

Wee et al., in 2017 and 2018, studied 752 patients who underwent breast explant and observed that patients with breast implants with symptoms of BII had significant, immediate, and sustained improvement in 11 common symptoms after surgery and that this improvement was maintained beyond the immediate postoperative period21. This demonstrates that the data we obtained between the explant surgery and the time of application of the questionnaire (median of 14 months) reflect a trend already observed in other studies.

Miranda, in 2020, when studying 15 patients undergoing explant, described that the most common symptoms such as myalgia, arthralgia, chronic fatigue, dry skin and hair improved in more than 80% of patients and 100% of patients with symptoms of cognitive impairment, fever and itching22. Our study observed improved arthralgia symptoms in 62%, chronic fatigue in 84%, cognitive disorders in 85%, and fever in 57%.

Miseré & van der Hulst, in 2020, when studying 197 patients undergoing breast explant, described that patients with symptoms of BII23 performed one in nine explants. About 60% of these patients experienced an improvement in their complaints after implant removal. In our study, 84% of patients had three or more symptoms of BII and had an improvement rate of 66.1% after explant.

One of the biggest fears when recommending explant surgery is the possibility of patient regret. The regret would be both for the aesthetic issue of not being well accepted with small breasts and for retractions and adhesions that could arise after the explant accompanied by the absence of improvement in BII symptoms. There is a great discussion about the aesthetic result of breast explant surgeries; many surgeons believe that the body appearance after the intervention is frustrating and disharmonious.

In the opinion of the patients in our study, this did not occur. The regret of having had the explant surgery was only 0.6%. We could observe, with statistical significance, that the patients considered themselves more beautiful after implant placement and that this perception of body satisfaction remained after their removal. We found no difference in body selfassessment when comparing the patients while they had the implants and after the explant surgery. Visual scales of body satisfaction are widely used to evaluate results in Plastic Surgery12.

These data obtained in our research are of vital importance for us to understand that, not always, the aesthetic ideal of the surgeon is identical to that of the patient and that we must open our minds to understand the particularities of women who seek breast explants. Likewise, there was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction when we compared surgery with explant alone, explant with mastopexy, or explant associated with fat grafting. We believe that this finding demonstrates that the indications for associated surgeries were correctly performed; future research should focus on the indications for surgeries associated with breast explant.

Our data showed a regret rate of having had the implant surgery of 83.3%. These data must be carefully interpreted, as they conflict with the literature, which usually reports high satisfaction with the result obtained after the breast augmentation procedure with silicone implants24,25.

Support groups on social networks helped in the decision to perform the explant in 87.2% of the patients participating in our research, while news in newspapers, magazines or websites contributed to the decision of 46.5%. Literature shows us that about 98% of women diagnosed with BII use online support networks (Facebook and Instagram groups), and 62% of them report that participation in groups made them more alert about the diagnosis and fearful of the development of symptoms. symptoms5.

Considering the concerns of women with silicone implants and long-term research studying nearly 100,000 individuals with breast implants that demonstrated higher rates of autoimmune disease in people with breast implants, we must empathize with the concerns of our patients and recognize the potential reality of BII symptoms26,27.

We observed that the physician’s advice who placed the silicone helped in the decision to perform the explant in only 32.9% of the patients. It is important that our response offers real assistance to those who need guidance and care. While our first impulse may sometimes be to discourage a patient from having the implant removed, we must remember that women are as empowered to have their implants removed as they were to have the silicone implanted in their bodies.

Like any plastic surgery, implant removal must be approached based on the best and latest scientific evidence and with a thorough understanding of the risks and benefits. We believe that a patient with any type of complaint related to her implants should first return to the surgeon who performed the implant, hoping that he or she is prepared to examine and help each patient reach a decision appropriate to their individual needs and beliefs28.

Often, the physician who diagnoses BII is not the plastic surgeon, as the patient does not correlate the symptoms with the implants and starts looking for other physicians such as rheumatologists and neurologists29. Even considering that you look for your surgeon, we know that it is a subject that is not widely disseminated with diagnostic scores, making the patient feel helpless, as professionals unaware of the disease can discredit the complaints and claim that the causes would be psychosomatic30. Therefore, it is essential to listen to the patient’s concerns and take the time to explain the potential risks and benefits of the various options. In the end, if the surgeon prefers not to perform the explant and the patient still wants this surgery, referral to a colleague with experience in this surgery may be the best alternative.28

In the research model we used, response rates were calculated by dividing the number of usable responses by the total eligible number in the chosen sample31. Charles-de-Sá et al., in 2019, considered a response rate of around 10% as adequate, stating that this value would be well above the average response rate of an SBCP questionnaire32. Our study obtained a rate of valid responses of 55.1%, allowing us to state that the results obtained significantly reflect the reality of the selected sample.

The internal validity of our data is very consistent; however, the external validity of our findings is not appropriate for the population with silicone breast implants since the main limitation of our study lies in the selection of the sample composed of 91, 7% of patients who had at least one symptom of BII while having breast implants. Therefore, generalization of our results to the general population is discouraged.

Our data are strictly related to patients who spontaneously wished to undergo an explant; our research was not designed to assess the prevalence or incidence of symptoms of BII or ASIA syndrome. This relationship should be studied in the future through epidemiological research with designs different from ours, ideally, population-based cohorts involving people with breast implants and people who have never had silicone implants.

Our patients showed a statistically significant change in BII symptoms. However, not all patients improved. Therefore, when talking to our patients, we must clarify that there is no guarantee that symptoms will improve with implant removal. On the other hand, several studies have shown improvement in symptoms in some patients without laboratory evidence of autoimmune disease10.

We do not have this very precise improvement parameter because there are patients who undergo explants without a precise pre-surgical clinical evaluation. At this point, some diagnoses are not performed, and, in the postoperative period of the explant, the symptoms of this undiagnosed or untreated disease will manifest. There is also the bias that it may have triggered another autoimmune disease when the prosthesis acted as a trigger.

Most autoimmune diseases cannot be cured after the trigger is fired and may alternate moments of improvement with worsening of clinical manifestations since remission does not depend only on the explant. Hypovitaminosis, decompensated chronic diseases, and emotional issues such as the pandemic moment can also somehow interfere with this evaluation. The diagnostic criteria for BII are vague and nonspecific; as a result, the phenomenon is difficult to identify and treat33.

We need to emphasize that medical science is always evolving and that many diseases and conditions remain poorly understood despite years of research. Staying up to date on breast implants means knowing about the interests and requests of patients and information brought by the media and studying the published literature and the reasons for the scarcity of evidence of the highest degree29.

We have not stopped looking for solutions to the many legitimate questions being raised, nor will we stop until the answers are found. Now, however, we need to help our patients understand their current options and the potential risks and benefits of each course of action, including the possibility of doing nothing28. We must rely on the best available scientific evidence to determine the most appropriate counseling for our patients considering physical symptoms and the impact of uncertainty. We cannot fail to value the motivations of our patients; we must seek to decipher the enigma of BII and ensure that our patients know that we will never stop seeking the best possible scientific evidence and excellence in medical care.

CONCLUSION

Some patients undergoing breast implant surgery have symptoms described as BII after having silicone implants, and most of these symptoms disappear with the removal of breast implants. Body self-satisfaction increases with the placement of breast implants and remains high after their removal. Patients who undergo explant surgery are often regretful of having had silicone implants, very satisfied with the decision to have them removed, and equally satisfied with the outcome of the breast explant surgery. Support groups in social networks were important in the decisionmaking of these patients.

REFERENCES

1. Goldenberg DC, Baroudi R. O problema dos implantes de silicone e o impacto na qualidade de vida. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(1):1.

2. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS). [Internet]. 2019 Plastic Surgery Statistics [a cesso 2021 Abr 27]. Disponível em: https://www.isaps.org/medical-professionals/isaps-global-statistics/

3. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP). [Internet]. Pesquisas [a cesso 2021 Abr 27]. Disponível em: http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/pesquisas/

4. American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) [Internet]. 2019 Aesthetic Plastic Surgery National Databank Statistics [acesso 2021 Abr 27]. Disponível em: https://www.sur-gery.org/sites/default/files/Aesthetic-Society_Stats2019Book_FINAL.pdf

5. Newby JM, Tang S, Faasse K, Sharrock MJ, Adams WP. Understanding Breast Implant Illness. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41(12):1367-79.

6. Bozola A. Passado, presente e futuro utilizando implantes mamários de silicone no Brasil, um relato de 45 anos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2020;35(4):505-13.

7. Cole NM. Consequences of the U.S. Food and Drug AdministrationDirected Morator ium on Silicone Gel Breast Implants: 1992 to 2006. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(5):1137-41.

8. Watad A, Rosenberg V, Tiosano S, Cohen Tervaert JW, Yavne Y, Shoenfeld Y, et al. Silicone breast implants and the risk of autoimmune/rheumatic disorders: a real-world analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(6):1846-54.

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Saline, Silicone Gel, and Alternative Breast Imp lants - Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff [Internet]. [a cesso 2021 Abr 27]. Disponível em: https://www.fda.gov/media/71081/download

10. Magnusson MR, Cooter RD, Rakhorst H, McGuire PA, Adams WP Jr, Deva AK. Breast Implant Illness: A Way Forward. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:74S-81S.

11. American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Procedural Statistics represent procedures performed by ASPS member surgeons certified by The American Board of Plastic Surgery as well as other physicians certified by American Board of Medical Specialties-recognized boards [Internet]. [acesso 2021 Abr 27]. Disponível em: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plasticsurgery-statistics

12. Clapham PJ, Pushman AG, Chung KC. A systematic review of applying patient satisfac tion outcomes in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(6):1826-33.

13. Tanna N, Calobrace MB, Clemens MW, Hammond DC, Nahabedian MY, Rohrich RJ, et al. Not All Breast Explants Are Equal: Contemporary Strategies in Breast Explantation Surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(4):808-18.

14. Peters W, Smith D, Fornasier V, Lugowski S, Ibanez D. An outcome analysis of 100 women after explantation of silicone gel breast implants. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39(1):9-19.

15. Caravantes-Cortes MI, Roldan-Valadez E, Zwojewski-Martinez RD, Salazar-Ruiz SY, Carballo-Zarate AA. Breast Prosthesis Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Management Algorithm. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020;44(5):1423-37.

16. Shoaib BO, Patten BM, Calkins DS. Adjuvant breast disease: an evaluation of 100 symptomatic women with breast implants or silicone fluid injections. Keio J Med. 1994;43(2):79-87.

17. Graf RM, Closs Ono MC, Pace D, Balbinot P, Pazio ALB, de Paula DR. Breast Auto-augmentation (Mastopexy and Lipofilling): An Option for Quitting Breast Implants. Aest hetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(5):1133-41.

18. Maijers MC, de Blok CJ, Niessen FB, van der Veldt AA, Ritt MJ, Winters HA, et al. Women with silicone breast implants and unexplained systemic symptoms: a descriptive cohort study. Neth J Med. 2013;71(10):534-40.

19. de Boer M, Colaris M, van der Hulst RRWJ, Cohen Tervaert JW. Is explantation of sili cone breast implants useful in patients with complaints? Immunol Res. 2017;65(1):25-36.

20. Colaris MJL, de Boer M, van der Hulst RR, Cohen Tervaert JW. Two hundreds cases of ASIA syndrome following silicone implants: a comparative study of 30 years and a review of current literature. Immunol Res. 2017;65(1):120-8.

21. Wee CE, Younis J, Isbester K, Smith A, Wangler B, Sarode AL, Patil N, et al. Understanding Breast Implant Illness, Before and After Explantation: A Patient-Reported Outcomes Study. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;85(S1 Suppl 1):S82-6.

22. Miranda R. O explante em bloco de prótese mamária de silicone na qualidade de vida e evolução dos sintomas da síndrome ASIA. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2020;35(4):427-31.

23. Miseré RML, van der Hulst RRWJ. Self-Reported Health Complaints in Women Under going Explantation of Breast Implants. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42(2):171-80.

24. Roncatti C, Batista KT, Roncatti Filho C. Escolha da técnica de mastoplastia de aumento: uma ferramenta na prevenção de litígio médico. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(2):253-9.

25. Santos GR, de-Araújo DC, Vasconcelos C, Chagas RA, Lopes GG, Setton L, et al. Impacto da mamoplastia estética na autoestima de mulheres de uma capital nordestina. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34(1):58-64.

26. Coroneos CJ, Selber JC, Offodile AC 2nd, Butler CE, Clemens MW. US FDA Breast Implant Postapproval Studies: Long-term Outcomes in 99,993 Patients. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):30-6.

27. Keane G, Chi D, Ha AY, Myckatyn TM. En Bloc Capsulectomy for Breast Implant Ill ness: A Social Media Phenomenon? Aesthetic Surg J. 2021;41(4):448-59.

28. Mcguire PA, Haws MJ, Nahai F. Breast Implant Illness: How Can We Help? Aesthetic Surg J. 2019;39(11):1260-3.

29. Manahan MA. Adjunctive Procedures and Informed Consent with Breast Implant Ex plantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(5S):51S-57S.

30. Siling Y, Klietz ML, Harren AK, Wei Q, Hirsch T, Aitzetmüller MM. Understanding Breast Implant Illness: Etiology is the Key. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42(4):370-7.

31. Sheehan KB. E-mail Survey Response Rates: A Review. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2001;6(2).

32. Charles-de-Sá L, Gontijo-Deamorim NF, Albelaez JP, Leal PR. Perfil da cirurgia de aumento de mama no Brasil. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34(2):174-86.

33. Marano AA, Cohen MH, Ascherman JA. Resolution of Systemic Rheumatologic Sympt oms following Breast Implant Removal. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(5):e2828.

1. Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

2. Sistema de Saúde Mãe de Deus, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

3. Hospital Erasto Gaertner, Serviço de Cirurgia Plástica e Microcirurgia, Curitiba,

PR, Brazil

4. Hospital Vale Paraibano de Cirurgias, Taubaté, SP, Brazil

5. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Hospital Universitário, Florianópolis,

SC, Brazil

DSV Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Statistical analysis, Final approval of the manuscript, Data Collection, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Resource Management, Project Management, Investigation, Methodology, Carrying out operations and/or experiments, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

WMI Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Final approval of the manuscript, Data Collection, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Project Management, Investigation, Methodology, Carrying out operations and/or experiments, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

FC Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Statistical analysis, Final approval of the manuscript, Data Collection, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Resource Management, Project Management, Investigation, Methodology, Carrying out operations and/or experiments, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Proofreading and Editing, Supervision, Visualization.

RVJ Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Final approval of the manuscript, Data Collection, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Resource Management, Project Management, Investigation, Methodology, Conducting operations and/or experiments, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

AG Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Final approval of the manuscript, Data Collection, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Project Management, Investigation, Methodology, Carrying out operations and/or experiments, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Visualization.

Corresponding author: Denis Souto Valente, R. Antônio Carlos Berta 475 - 702, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, Zip Code: 91340-020, E-mail: denisvalentedr@gmail.com

Article received: May 11, 2021.

Article accepted: July 14, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter