Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 - Issue 2

Socioeconomic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among plastic surgeons in Brazil

Impacto socioeconômico da pandemia da COVID-19 entre cirurgiões plásticos do Brasil

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Global sanitary crisis caused by the spread of COVID-19 induced many health services to stop performing non-urgent surgical procedures. In the scenario of plastic surgery, where most procedures are elective, socioeconomic consequences are estimated for these specialists. The objective of this study is to measure this impact.

Methods: Effects of the pandemic within the clinical practice of Brazilian plastic surgeons were investigated through an online questionnaire addressed to members of the Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica.

Results: A survey was applied to 645 surgeons. Most respondents reported operation restrictions on procedures and income reduction, especially in regions severely affected by the pandemic. Plastic surgeons with more than 10 years of experience were the most affected. High contamination rates, mental overload, decreased physical activity, and psychiatric medications have also been reported.

Conclusion: COVID-19 pandemic brought changes to the personal and professional life of the Brazilian plastic surgeon. Due to the significant reduction in the workload, there were financial impacts on specialists from all country regions, besides physical and mental health issues. Adaptations were mandatory to maintain services and explore new areas of activity to supply the low demand for cosmetic surgery during the crisis.

Keywords: Coronavirus infections; Pandemics; Socioeconomic factors; Quality of life; Surgery, plastic.

RESUMO

Introdução: Devido à crise sanitária mundial provocada pela disseminação da COVID-19, muitos serviços de saúde interromperam a realização de procedimentos cirúrgicos não urgentes. No cenário da Cirurgia Plástica, no qual a maioria das cirurgias são eletivas, estimam-se consequências socioeconômicas a estes especialistas. O objetivo deste estudo é dimensionar este impacto.

Métodos: Os efeitos da pandemia dentro da prática clínica dos cirurgiões plásticos brasileiros foi investigada por meio de um questionário on-line, endereçado aos associados da Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica.

Resultados: A pesquisa foi aplicada a 645 cirurgiões. A maioria dos entrevistados relatou restrições operacionais à realização de procedimentos e redução da renda, sobretudo nas regiões severamente afetadas pela pandemia. Cirurgiões plásticos com mais de 10 anos de formação foram os mais prejudicados. Elevada taxa de contaminação, sobrecarga mental, diminuição na prática de atividades físicas e uso de medicações psiquiátricas também foram relatados.

Conclusão: A pandemia da COVID-19 trouxe mudanças no cenário pessoal e profissional do cirurgião plástico brasileiro. Devido à importante redução no volume de trabalho, houve impacto financeiro nos especialistas de todas as regiões do país, além de reflexos na saúde física e mental. Adaptações foram necessárias para manutenção dos atendimentos, além de exploração de novas áreas de atuação para suprir a baixa demanda de cirurgias estéticas durante a crise.

Palavras-chave: Infecções por coronavírus; Pandemias; Fatores socioeconômicos; Qualidade de vida; Cirurgia plástica

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic, a potentially serious respiratory disease, is considered one of the biggest health and economic crises in history. Since its emergence and dissemination, the impacts generated by the disease on health systems have spread at an overwhelming pace, reaching all regions of the planet1-3.

When writing this article, Brazil was approaching 370,000 deaths from the disease, with estimates of 14 million people infected, which is still underestimated due to the low population testing rate and underreporting.

The pandemic has caused enormous challenges for healthcare organizations and professionals worldwide. The adoption of safety protocols, team training, use of personal protective equipment and an increase in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds have become essential practices in all countries4. The economic issue within health systems has also become a factor of concern for managers and professionals in the area, given that the impact on the suspension of care has also contributed to the reduction of revenue within the sector5,6.

In the United States of America (USA), elective surgeries correspond to a significant share of the revenue of hospitals and private clinics, and the USA healthcare system represents approximately 18% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in revenue. The economic impacts projected in the USA indicate that the suspension of these surgeries can lead to the bankruptcy of dozens of private health services, with an estimated annual federal revenue drop of 12.5%7.

According to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS), Brazil is the country that performs the most plastic surgeries in the world, responsible for almost 1.5 million procedures in 20188 alone. The suspension of consultations and elective surgeries has become the main recommendation to prevent COVID-19 among Brazilian plastic surgeons to protect the population. Within this context, this study seeks to understand the dimension of the economic damage caused by the first wave of the pandemic on plastic surgeons working in Brazil, also correlating data on these professionals’ physical and mental health.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the socioeconomic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic among Brazilian plastic surgeons in different contexts and regions through a directed online questionnaire.

METHODS

The authors created a structured, multiplechoice, online questionnaire directed to all plastic surgeons associated with the Brazilian Plastic Surgery Society (in portuguese Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica - SBCP). The questionnaire was developed on the “Google Docs” platform, consisting of 31 questions, divided into five blocks (Table 1) and addressed directly to professionals through social networks and registered email addresses, with support from the SBCP in disseminating research to associated physicians.

| Demographic Block | No | % | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P03 | What is your age? <30 years |

2 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| 30 - 35 years | 25 | 9.3 | 0.002 | |

| 36 - 40 years | 48 | 17.9 | 0.823 | |

| 41 - 45 years | 50 | 18.7 | Ref. | |

| 46 - 50 years | 37 | 13.8 | 0.128 | |

| 51 - 55 years | 30 | 11.2 | 0.015 | |

| 56 - 60 years | 22 | 8.2 | <0.001 | |

| 61 - 65 years | 33 | 12.3 | 0.042 | |

| 66 - 70 years | 14 | 5.2 | <0.001 | |

| > 70 years | 7 | 2.6 | <0.001 | |

| P04 | What’s your sex? | |||

| Female | 130 | 20.1 | ||

| Male | 515 | 79.9 | <0.001 | |

| P05 | How long have you been working as a Plastic Surgeon? | |||

| <5 years | 110 | 17 | <0.001 | |

| 5-10 years | 109 | 16.9 | <0.001 | |

| 10-20 years | 185 | 28.7 | <0.001 | |

| >20 years | 241 | 37.4 | <0.001 | |

| P06 | In which state of Brazil do you currently operate? | |||

| Midwest | 81 | 12.5 | <0.001 | |

| Northeast | 82 | 12.7 | <0.001 | |

| North | 16 | 2.5 | <0.001 | |

| Southeast | 341 | 52.9 | Ref. | |

| South | 125 | 19.4 | <0.001 | |

| P07 | In which sector do you work? | |||

| Both services | 251 | 38.9 | <0.001 | |

| Private service | 388 | 60.2 | Ref. | |

| Public service | 6 | 0.9 | <0.001 | |

| Emotional Block | N | % | p-valor | |

| P28 | Did you use any psychiatric medication that you did not use previously during the pandemic? | |||

| No | 597 | 92.5 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 48 | 7.4 | ||

| P29 | Have you felt mentally overwhelmed at any point this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic? | |||

| No | 194 | 30.1 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 451 | 69.9 | ||

| P30 | Have you started any exercise/sports/healthy habits routine that you did not do prior to the pandemic? | |||

| No | 430 | 66.7 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 215 | 33.3 | ||

| P31 | Have you SUSPENDED any exercise/sports/healthy habits routine you performed before the pandemic? | |||

| No | 252 | 39.1 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 393 | 60.9 | ||

| Contamination Block | N | % | p-valor | |

| P10 | Do any of the services you work as a plastic surgeon serve COVID-19+ patients? | |||

| No | 239 | 37.1 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 406 | 62.9 | ||

| Contamination Block | N | % | p-valor | |

| P11 | Do you work directly with COVID19+ patients? | |||

| No | 479 | 74.2 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Approach to pressure injuries. | 51 | 7.9 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Urgent surgeries in patients without a confirmed diagnosis. | 31 | 4.8 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Oncological surgeries. | 56 | 8.7 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Care in ICU, SAMU and field hospitals. | 28 | 4.4 | <0.001 | |

| P19 | Have you been affected by COVID 19? | |||

| No. | 590 | 91.5 | Ref. | |

| Yes. Asymptomatic form (positive exams only). | 19 | 2.9 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Mild symptomatic form (home treatment). | 36 | 5.6 | <0.001 | |

| P20 | Have you returned to your elective office activities? I did not return to activities. | 99 | 15.3 | <0.001 |

| I never stopped. | 51 | 7.8 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. I have returned. | 495 | 76.8 | Ref. | |

| P21 | If you have already returned, how many days have you been stopped? | |||

| I still have not returned to activities. | 77 | 11.8 | <0.001 | |

| Up to 7 days. | 45 | 7.0 | <0.001 | |

| 7-14 days. | 45 | 7.0 | <0.001 | |

| 14-21 days. | 54 | 8.4 | <0.001 | |

| 21-30 days. | 65 | 10.1 | <0.001 | |

| >30 days. | 359 | 55.7 | Ref. | |

| Block Changes | N | % | p-valor | |

| P12 | Has the COVID-19 pandemic reduced your workload (within the field of Plastic Surgery)? | |||

| No. There was an increase in the volume of work. | 3 | 0.5 | <0.001 | |

| No. The volume remained constant. | 8 | 1.2 | <0.001 | |

| Yes, but only in the private service. | 46 | 7.1 | <0.001 | |

| Yes, but only in public service. | 5 | 0.8 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. There was a reduction in the volume of work. | 583 | 90.4 | Ref. | |

| P13 | Was there an institutional restriction of ELECTIVE plastic surgeries in your service? | |||

| No. | 42 | 6.5 | <0.001 | |

| Yes, but only in the private service. | 33 | 5.1 | <0.001 | |

| Yes, but only in public service. | 17 | 2.6 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. | 553 | 85.7 | Ref. | |

| P14 | Was there an institutional restriction on URGENCY plastic surgery in your service? | |||

| No. | 451 | 69.8 | Ref. | |

| Yes, but only in the private service. | 29 | 4.5 | <0.001 | |

| Yes, but only in public service. | 28 | 4.4 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. | 137 | 21.2 | <0.001 | |

| P15 | Concerning March-April/2019, what was the percentage of REDUCTION of elective surgeries observed in YOUR practice for the same period in 2020? | |||

| There was an increase in elective surgical procedures. | 10 | 1.6 | <0.001 | |

| I do not perform elective surgical procedures | 3 | 0.5 | <0.001 | |

| <30% | 14 | 2.1 | <0.001 | |

| 30-60% | 64 | 9.9 | <0.001 | |

| 60-90% | 237 | 36.7 | <0.001 | |

| >90% | 317 | 49.1 | <0.001 | |

| Block Changes | N | % | p-valor | |

| P16 | Concerning March-April/2019, what was the percentage of REDUCTION of NON-SURGICAL procedures (Botox/fillers/etc.) observed in YOUR practice for the same period in 2020? | |||

| There was an increase in the number of non-surgical procedures | 17 | 2.6 | <0.001 | |

| I do not perform non-surgical procedures | 81 | 12.5 | <0.001 | |

| <30% | 18 | 2.9 | <0.001 | |

| 30-60% | 80 | 12.4 | <0.001 | |

| 60-90% | 171 | 26.5 | <0.001 | |

| >90% | 278 | 43.2 | <0.001 | |

| P17 | Your operating costs (rents/office/secretary/suppliers) remained constant during the Pandemic? | |||

| No. They increased. | 8 | 1.2 | <0.001 | |

| No. They have been reduced. | 177 | 27.4 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. They remained the same. | 460 | 71.3 | Ref. | |

| P18 | What was, on average, the percentage REDUCTION of your revenue due to the pandemic? | |||

| <30% | 35 | 5.4 | <0.001 | |

| 30-60% | 159 | 24.6 | <0.001 | |

| 60-90% | 279 | 43.3 | <0.001 | |

| >90% | 172 | 26.6 | <0.001 | |

| Prevention block | N | % | p-valor | |

| P08 | Was there a measure of social isolation in your main city of operation? | |||

| No | 2 | 0.3 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 643 | 99.7 | ||

| P09 | Was there LOCKDOWN in your main professional city? | |||

| No | 381 | 59 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 264 | 41 | ||

| P22 | Are patients undergoing surgery at your service tested for COVID-19 using any method? | |||

| No. | 273 | 42.3 | Ref. | |

| Yes. RT-PCR only. | 151 | 23.4 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Only serology. | 108 | 16.7 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Serology + RT-PCR. | 113 | 17.5 | <0.001 | |

| P23 | Are your team members, or have they been tested for COVID-19 with any method before restarting activities? | |||

| No. | 374 | 58.0 | Ref. | |

| Yes. RT-PCR only. | 54 | 8.4 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Only serology. | 124 | 19.2 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Serology + RT-PCR. | 93 | 14.4 | <0.001 | |

| P24 | In the face-to-face care of your patients, has there been a change in the care routine? (More than one option available) | |||

| No. | 4 | 0.6 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Disposable apron | 93 | 14.4 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Face shield | 116 | 18.0 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. Mask and alcohol-gel | 603 | 93.5 | Ref. | |

| Yes. Mask N95/similar. | 190 | 29.5 | <0.001 | |

| P25 | In elective surgeries, were clauses about COVID-19 included in the surgical consent form? | |||

| No. | 70 | 12.1 | <0.001 | |

| No. | 70 | 12.1 | ||

| P26 | Have you used teleconferencing and/or social media (including WhatsApp) to serve patients during the pandemic? | |||

| No. | 211 | 32.7 | <0.001 | |

| Yes. | 434 | 67.3 | ||

| P27 | Were you already using teleconferencing and/or social media (including WhatsApp) to serve patients before the pandemic? | |||

| No. | 346 | 53.6 | 0.009 | |

| Yes | 299 | 46.4 | ||

ICU: Intense Care Unit; SAMU: Emergency Care Services; RT-PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction Tests with Reverse Transcriptase.

For the assembly of the questionnaire, a similar model from the European Society of Plastic Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery (ESPRAS)9 was used as a basis. The questionnaire was designed to ensure the anonymity of respondents. The average response time was calculated from 2 to 3 minutes.

Considering the population of 6,000 Brazilian plastic surgeons10, the number of responses necessary to reach the statistically representative parameter, with a standard error of 5% and a CI of 95%, was 362. The questionnaire application started in the first week of June 2020. After 20 days, 645 responses were collected. The data obtained were transported and organized in the Excel platform, and the statistical evaluation with data crossing was performed afterward.

Data collected were grouped into domains, referring to demographic data (identity, gender), professional training (training time and professional performance profile), health data (positivity for COVID-19) and activity during the pandemic (lockdown tax and isolation, restriction to elective and emergency surgeries). The data are compared according to the regions of the country. The interviewees were also divided into two groups according to the training time. Trained less than 10 years ago and more than 10 years ago were compared concerning the parameters studied.

All statistical analyzes were performed using Stata 14.2 software, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA.

RESULTS

Responses were obtained from all country regions, including 23 of the 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District. The states without representatives in the survey were Acre, Tocantins and Amapá. The distribution by gender followed a ratio of approximately 4:1, with 515 men and 130 women. The Southeast Region was the most represented, corresponding to 52.9% of responses, followed by the South Region, with 19.4% of responses, Midwest Region, with 12.5%, Northeast Region, with 12.7%, and North Region with 2.5%. Approximately 34% of respondents had up to 10 years of graduation, while 66% had more than 10 years of graduation in plastic surgery. The sociodemographic profile according to the region is shown in Table 2.

| Region | South | Southeast | Midwest | North | Northeast | BRAZIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Answers | 125 (19.4%) | 341 (52.9%) | 81 (12.5%) | 16 (2.5%) | 82 (12.7%) | 645 |

| Sex | 80%M : 20% F | 81%M : 19%F | 80%M : 20%F | 100%M | 68%M : 32%F | 79.9%M : 20.1%F |

| Service in which you operate Private SUS Both |

68.8% 0.8% 30.4% |

61.6% 0.9% 37.5% |

61.7% - 38.3% |

50% - 50% |

41.5% 2.4% 56.1% |

60.2% 0.9% 38.9% |

| Training time | ||||||

| <5 years 5-10 years 10-20 years >20 years |

12.8% 16% 32% 39.2% |

16.7% 13.5% 29% 40.8% |

30.9% 21% 23.4% 24.7% |

12.5% 31.25% 31.25% 25% |

12.2% 25.6% 26.8% 35.4% |

17% 16.9% 28.7% 37.4% |

| Isolation rate | 100% | 99.4% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 99.7% |

| Lockdown rate | 43.2% | 30.8% | 37% | 68.7% | 57.3% | 41% |

| Covid-19+ No Yes, asymptomatic Yes, symptomatic |

96.8% 1.6% 1.6% |

90% 3.2% 6.8% |

97.5% - 2.5% |

75% - 25% |

86.6% 7.3% 6.1% |

91.5% 2.9% 5.6% |

| Institutional restriction on elective surgeries | 92.8% | 93.8% | 90.1% | 93.8% | 96.3% | 993.4% |

| Institutional restriction on emergency surgeries | 25.6% | 34.6% | 18.5% | 25% | 31.7% | 30.1% |

M: Male; F: Female; SUS: Brazilian Public Health System.

The South Region had the highest proportion of surgeons working exclusively in the private sector, representing 68.8% of the responses, while 30.4% reported working in the public and private sectors. The Southeast Region showed 61.6% exclusive work in the private network and 37.5% in both networks. In the Midwest Region, 61.7% worked only in the private network and 38.3% in both (public and private). The Northeast Region pointed to 41.5% of physicians working exclusively in the private network and 56.1% in both networks. Finally, 50% answered working in the private network in the North Region and 50% in both services. Only 0.9% of the plastic surgeons interviewed answered that they only work in the public network.

In all regions of Brazil, there was some measure of social isolation in the cities where the surgeons interviewed were primarily active. However, more severe restrictions, such as lockdown, were adopted heterogeneously across the five regions. According to the interviewees, the North and Northeast were the most that implemented these measures, with 68.7% and 57.3%, respectively. The South was the third region that most adopted the complete closure of commercial activities, with 43.2%. This rate was 37% and 30.8% in the Midwest and Southeast.

It was also questioned whether the service in which the plastic surgeons worked cared for patients with suspected or confirmed infection by the new coronavirus. Respondents from the South, Southeast, Midwest, Northeast, and North showed the following attendance rates: 58%, 68%, 50%, 81% and 62%, respectively. However, in these same regions, there was a direct action by the plastic surgeon with COVID-positive patients in only 12%, 26%, 34%, 41%, and 63%. On occasions when there was direct care for the positive COVID patient, there was a difference between acting as a clinician/intensivist/screening physician and participating as a plastic surgeon (oncological, traumatic, or reparative surgeries). In the latter situation, it was observed that the participation of plastic surgeons in their area of expertise occurred in 8.8% in the South, 19.6% in the Southeast Region; 23.8% in the Midwest Region; 33.3% in the Northeast Region and 56.25% in the North Region.

When the criterion adopted for analysis was the type of service in which the surgeon was inserted (public or private), significant variations between the responses were observed. On occasions when the physician worked exclusively in the private service, there was no direct work with infected patients in 87% of the responses; on the other hand, in cases in which they worked both in the private and public network, this number dropped to 53.1%, indicating a greater presence of the plastic surgeon in the front line in the public network.

Regarding the reduction in the volume of work in Plastic Surgery, there was a significant drop in all the analyzed states. The North was the most impacted, one of the regions most affected by the pandemic during the first wave, with 93.7% of respondents revealing that they had noticed some degree of reduction in the volume of work. The Northeast was in second place, with 82.9% of respondents referring to a reduction in the volume of work. It was also observed that there were restrictions imposed institutionally for elective surgeries, by the health services where the interviewees work, in all country regions. On the other hand, emergency procedures had little impact. Only 30% of respondents across the country revealed institutional limitations for this type of surgery.

Analyzing the financial issue, the data collected show that operating costs (rents, suppliers, secretaries, etc.) remained constant for 71.4% of respondents, reducing to 27.4% and increasing to only 1.2%. Despite this, the monthly income of plastic surgeons during the months of March-April 2020 (when the quarantine period was declared in the country) showed a significant reduction in all regions analyzed (Table 3).

| Region | South | Southeast | Midwest | North | Northeast | BRAZIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return to activities | 92.8% | 81.2% | 98.7% | 67.8% | 75.6% | 76.8% |

| Downtime | ||||||

| <7 days | 3.2% | 7.6% | 11.1% | - | 7.3% | 7% |

| 7-14 days | 10.4% | 4.8% | 14.8% | 6.25% | 2.4% | 7% |

| 14 - 21 days | 11.2% | 7% | 12.4% | 6.25% | 6.1% | 8.4% |

| 21 - 30 days | 16.8% | 9.3% | 11.1% | --- | 4.9% | 10.1% |

| >30 days | 52% | 56.9% | 50.6% | 68.75% | 58.6% | 55.7% |

| Did not return | 6.4% | 14.4% | --- | 18.75% | 20.7% | 11.8% |

| ↓ Elective surgeries | ||||||

| <30% | 3.2% | 4.7% | 2.5% | - | 2.4% | 4.2% |

| 30-60% | 16.8% | 5.3% | 27.2% | 6.25% | 2.4% | 9.9% |

| 60-90% | 48% | 33.7% | 50.6% | 18.75% | 35.4% | 36.7% |

| >90% | 32% | 56.3% | 19.7% | 75% | 59.8% | 49.1% |

| ↓ Non-surgical procedures | ||||||

| Does not perform | 14.8% | 12.3% | 6.2% | 25% | 13.4% | 12.5% |

| <30% | 5.9% | 15% | 7.4% | --- | 3.7% | 5.4% |

| 30-60% | 17.3% | 7% | 25.9% | 12.5% | 3.6% | 12.4% |

| 60-90% | 38% | 20.4% | 33.3% | 18.75% | 23.3% | 26.5% |

| >90% | 24% | 45.3% | 27.2% | 43.75% | 56% | 43.2% |

| ↓ Net Revenue | ||||||

| <30% | 5.8% | 5.3% | 8.8% | - | 6.1% | 5.4% |

| 30-60% | 29.9% | 19.5% | 34.2% | 18.75% | 26.8% | 24.6% |

| 60-90% | 45.3% | 43.8% | 48.1% | 43.75% | 35.4% | 43.3% |

| >90% | 19% | 31.4% | 8.9% | 37.5% | 31.7% | 26.6% |

The North Region was the one that presented the greatest impact on net gains: 81.25% of the interviewees revealed a drop of more than 60% in their revenues concerning the same months of the previous year. In the Southeast, this number was 75.2%. Compared to the previous year, Northeast, South and Central-West showed 67.1%, 64.3% and 57% reductions greater than 60% in revenue. Brazil presented drops of more than 90% in income for 26.3% plastic surgeons. Less than 1% of respondents reported an increase in revenue.

When stratified by training time, it is noted that the drops in revenue were more expressive among plastic surgeons trained more than 10 years ago. More than 60% reduction in revenue was identified in this group in 76.2% of respondents, against 57.7% of those who graduated less than 10 years ago (Table 4). Among the most experienced surgeons, 87.1% responded with more than 60% reduction in the number of surgical procedures performed, while non-surgical procedures (botulinum toxin injection, fillers, and other ancillary procedures) were 73.4%. In the group with less than 10 years of experience in Plastic Surgery, a drop of more than 60% in performing surgeries was identified in 80.9% and 61.9% in non-surgical procedures.

| <10 years of graduation (n=220) | >10 years of graduation (n=425) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service | Number of responses | Percentage | Number of responses | Percentage |

| Private SUS Both |

124 3 93 |

56.4% 1.4% 42.2% |

264 3 158 |

62.1% 0.7% 37.2% |

| Where you work as a plastic surgeon, do you attend COVID-19? | ||||

| Yes | 152 | 69.1% | 254 | 59.8% |

| No | 68 | 30.9% | 171 | 40.2% |

| Do YOU work directly with COVID-19? Yes Urgent, oncological, reparative and pressure injuries surgeries SAMU, ICU, field hospitals No |

83 66 17 137 |

37.7% 30% 7.7% 62.3% |

83 72 11 342 |

19.5% 16.9% 2.6% 80.5% |

| Affected by COVID-19? | ||||

| Yes | 30 | 13.7% | 25 | 5.9% |

| No | 190 | 86.3% | 400 | 94.1% |

| Did you feel mentally overwhelmed? Yes No |

160 60 |

72.7% 27.3% |

291 134 |

68.5% 31.5% |

| Did you use new psychiatric medication in the pandemic? | ||||

| Yes | 17 | 7.7% | 31 | 7.3% |

| No | 203 | 92.3% | 394 | 92.7% |

| Did you start new physical activity during the pandemic? Yes No |

66 154 |

30% 70% |

149 276 |

35% 65% |

| Did you suspend physical activity during the pandemic? | ||||

| Yes | 145 | 65.9% | 248 | 58.4% |

| No | 75 | 34.1% | 177 | 41.6% |

| ↓ Net Revenue <30% |

18 | 8.2% | 17 | 4% |

| 30-60% | 75 | 34.1% | 84 | 19.8% |

| 60-90% | 94 | 42.7% | 185 | 43.5% |

| >90% | 33 | 15% | 139 | 32.7% |

SUS: Brazilian Public Health System; SAMU: Emergency Care Services; ICU: Intense Care Unit.

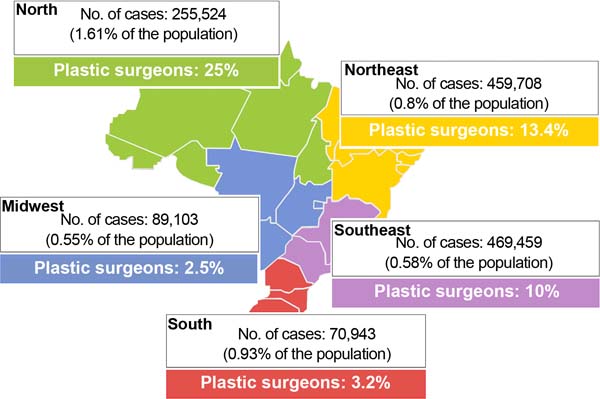

Diagnosis of COVID-19 was made in 8.5% of respondents. The most affected were in the North Region, where 25% of respondents confirmed the disease was affected, followed by the Northeast (13.4%) and Southeast (10%). These data are represented in Figure 1. It was also observed that younger individuals (i.e., those with less training time) were more diagnosed than older ones (13.7% versus 5.9%). There were no reports of serious forms. All had the mild form (outpatient treatment) or asymptomatic (positive exams, without clinical repercussions).

Regarding the return to work activities, 76.9% of respondents said they had already resumed their routines when they answered the questionnaire (June 2020). This contingent was more expressive in the Center-West (98.7%) and South (92.8%). Doctors working in the Southeast, Northeast and North had already resumed their usual activities in 81.2%, 75.6%, and 67.8% of the cases. The suspension of activities was longer than 30 days for 52% of respondents in the South Region, 56.9% in the Southeast; 50.6% in the Midwest; 58.6% in the Northeast and 68.75% in the North of the country. At the national level, 15.3% of plastic surgeons in Brazil had not yet returned to activities at the time of the survey, while 7.6% revealed that they had never suspended their activities.

Respondents were asked about the adaptations made in the services where they work for patient care. In this field, 42.3% of plastic surgeons in Brazil stated that they did not perform any preoperative testing in their services, while 57.6% reported using at least one laboratory method (Polymerase Chain Reaction Tests with Reverse Transcriptase (RT-PCR) or serology) for preoperative screening. When the question referred to the testing of the team involved in patient care, 58% of physicians stated that they did not perform any test, while 42% used some of the available methodologies.

In face-to-face patient care, some form of PPE was introduced in 99.4% of the cases, with a common surgical mask combined with hand hygiene with gel alcohol being the most adopted measure (93.5%). Use of N95 or similar masks was reported by 29.5%, “face shields” by 18% and disposable aprons by 14.4%. Clauses about COVID-19 were also included in the surgical consent form for 87.9% of respondents. The use of remote service methods (teleconferencing or social media) showed a growth of 13.7% after the beginning of the pandemic.

As for personal habits, use of psychiatric medications, and mental stress in professionals, 69.9% of the plastic surgeons interviewed reported some form of mental overload. In addition, 7.4% of the professionals interviewed reported having started using some psychiatric medication during the pandemic. When stratified by gender, there was no difference in mental burden rates between men and women. However, new psychiatric medication use incidence was higher among female plastic surgeons (14.8% versus 5.1%). New physical activities and healthier lifestyle habits were started in 33.3% of respondents during the pandemic, while 60.9% revealed that they had interrupted such activities (which they had previously performed) during this period.

DISCUSSION

Brazil is a country of continental dimensions and geographic specificities, which, associated with different public policies in controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, contribute to heterogeneous scenarios within the national territory. The impacts of the pandemic were felt throughout the Brazilian population and in all economic sectors. Plastic surgeons, not being shielded from the effects of the health crisis installed in the country, were also affected.

Although not previously validated, the online questionnaire was an instrument created specifically for the moment experienced by the community, having intrinsic value based on its originality and its broad approach to the aspects that affected the daily lives of the surgeons interviewed.

In this survey, we observed that plastic surgeons had timid participation in the treatment and follow-up of infected patients. Across the country, only 25.8% of respondents have acted to manage patients with COVID-19. The exception was the North Region, where 63% of respondents acted directly against the pandemic. In the other regions, this percentage was less than 50%. A possible explanation for this phenomenon lies in the lack of medical workforce in the North of the country, a chronic problem of dispersion and fixation of professionals far from large centers, with the need to mobilize these surgeons for other areas of care and their main training. Thus, it is understood that medical specialties primarily not associated with the demands of COVID-19 were recruited to treat these patients.

Although Plastic Surgery is not directly involved in the clinical treatment of those infected with the new coronavirus, the specialty also plays a role in treating these patients. Among those interviewed, 11.7% said they continued to perform urgent plastic surgery in patients with COVID-19, while 8.6% responded that they performed oncological surgeries in this population.

In addition, the specialty found in the management of pressure injuries is an important area of action in this context. Among those interviewed, 7.8% are involved in treating this complication, which has been increasing in incidence due to the increase in the population of patients in ICU beds during the pandemic. In some centers, teams of plastic surgeons were reorganized to work exclusively to treat this type of injury. Thus, even when called upon to perform some care for the coronavirus patient, plastic surgeons remained within their own field.

Another important characteristic noted was the difference in the participation of plastic surgeons in the fight against the pandemic when evaluating the type of service in which they were previously inserted. It was observed that physicians working in the public service had greater participation than those affiliated exclusively with the private sector. This indicator shows the importance of the public sector in the care of patients affected by the new virus and reaffirms the role of the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) in the fundamental guarantee of the citizen’s right to access to health.

There was a significant drop in the volume of work and the monthly income of plastic surgeons across the country in the economic sphere. Despite this, this decline occurred disproportionately across regions. The North and Southeast regions were the most affected, coinciding with the regions most affected by COVID-19 in Brazil during the first wave. Again, this discrepancy can be explained by the late effects of public policies of social isolation, the closing of businesses, public awareness, and changes in the conduct of doctors themselves. It is interesting to note that 26.3% of those interviewed stated that they had suffered revenue reductions of more than 90%, a number probably associated with the almost complete suspension of elective work activities, especially within private services.

Although the disease has brought socioeconomic damage to all, it is important to emphasize that this impact was different when the interviewees were stratified by training time. The 10-year training time cutoff was considered a function of the average time for economic stabilization professionals within their area of e xpertise. The analysis showed that the reduction in revenue among the youngest (less than 10 years since graduation) was, on average, 77% lower than that suffered by the most experienced doctors. One possibility would be the fear of contamination among more experienced doctors and/or those with comorbidities. Furthermore, the higher infection rate among younger plastic surgeons can be explained by the greater exposure of these professionals, whose work routine was less impacted.

During the pandemic, there was only a 14% growth in distance service methods (teleconferencing or social media). This demonstrates that a large part of the specialty already used forms of communication and non-face-to-face follow-up with their patients through photos or conversations in applications. Still, the new reality of social isolation and the closing of offices allowed the expansion of this form of service.

As for changes in the work routine, almost all interviewees adopted some measure of personal protection and hygiene, such as masks and alcohol gel. However, most respondents do not perform any type of testing, serological or via RT-PCR, on their patients in the preoperative period. In addition, more than half do not track the disease in their teams. Still, 4 out of 5 physicians confirmed the inclusion of COVID-19 clauses in the surgical consent form for elective procedures. This data indicates that the rigor of the prevention of the new coronavirus was inferior to the fear of the judicialization of care, an increasingly common process within the specialty.

The pandemic also impacted the physical and mental health of physicians participating in the study. Of those interviewed, 70% reported some form of mental overload during the period. Among the causes, we can highlight social confinement, reduced monthly income, uncertainties about the future of the disease and less practice of usual physical activities. A reflection was the beginning of the use of psychiatric medications in the last three months, especially among women.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic brought changes in the personal and professional scenario of the Brazilian plastic surgeon. Due to the significant reduction in the volume of work, there was a financial impact on specialists from all country regions. Adaptations were necessary to maintain care, such as using PPE, testing patients and staff, applying specific consent forms, and expanding telemedicine. Although elective procedures have been restricted, many plastic surgeons have adapted to the new reality, performing emergency surgeries, reconstructions or even working on the front line. The authors suggest conducting new surveys for 2021, seeking to update the data presented and compare the effects of the first and second waves on plastic surgeons in Brazil.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Novel coronavirus (2019nCoV) situation report - 1.21 Jan uary 2020. [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020 [acesso 2020 Jun 28]. Disponível em: https://www.who.int/docs/defaultsource/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4

2. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020 [acesso 2020 Jun 28]. Disponível em: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/whodirector-general-s-opening-remarks-at-theme-dia-briefing-oncovid-19-11-march-2020

3. Trump DJ. Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coron avirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak [Internet]. Washington: White House; 2020. [acesso 2020 Jun 28]. Disponível em: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-nationalemergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19outbreak/

4. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. [Internet]. Baltimore: Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2020 [acesso 2020 Jun 28]. Disponível em: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/31820-cms-adult-elective-surgery-and-proceduresrecommendations.pdf

5. Setting PIS, Phase P. COVID-19: guidance for triage of nonemergent surgical proce dures. [Internet]. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2020 [acesso 2020 Jun 28]. Disponível em: https://www.facs.org/about-acs/covid-19/information-forsurgeons/triage

6. World Health Organization (WHO). Brazil demographic statistics 2020 [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020 [acesso 2020 Jun 28]. Disponível em: https://www.who.int/countries/bra/en/

7. Anoushiravani AA, O’Connor CM, DiCaprio MR, Iorio R. Economic Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis: An Orthopaedic Perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(11):937-41. DOI: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00557

8. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS). Global Survey 2018 - Press Release [Internet]. West Lebanon: ISAPS; 2019 [acesso 2020 Jun 28]. Disponível em: https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ISAPS-Global-Survey-2018-PressRelease-Portuguese.pdf

9. Giunta RE, Frank K, Costa H, Demirdöver C, di Benedetto G, Elander A, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on Plastic Surgery in Europe - An ESPRAS Survey. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2020;52(3):221-32. DOI: 10.1055/a-1169-4443

10. Bersan PN. O Brasil está em 2° lugar no ranking mundial de cirurgias plásticas, atrás dos Estados Unidos. [acesso 2020 Jul 1]. Disponível em: http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/blog/2019/12/06/cirurgia-plastica-responsavel/#:~:text=Conforme%20dados%20da%20Sociedade%20Brasi-leira,mas%20auxiliando%20no%20equil%C3%ADbrio%20geral

1. Universidade de São Paulo, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, São Paulo,

SP, Brazil

Institution: Universidade de São Paulo, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

RDAR Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Statistical analysis, Data collection, Conception and design of the study, Project Management, Research, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Review and Editing.

ICC Statistical analysis, Data collection, Conception and design of the study, Methodology, Writing - Review and Editing.

GMC Data Collection, Research, Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Review and Editing.

LA Statistical Analysis, Data Collection, Supervision.

GGRM Project Management, Writing - Drafting, Supervision.

DCG Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Proofreading and Editing, Supervision.

RG Writing - Preparation of the original, Writing - Proofreading and Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author: Renan Diego Américo Ribeiro, Avenida Dr. Enéas de Carvalho Aguiar, 255, serviço de Cirurgia Plástica, 8º andar, São Paulo, SP, Brazil Zip Code: 05403-900, E-mail: renanamericor@gmail.com

Article received: April 21, 2021.

Article accepted: May 18, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter