INTRODUCTION

Silicone breast implants (IMS) began to be used in the 1960s, more precisely in 1962.

Since then, thousands of women have undergone this procedure, mostly for aesthetic

purposes. Although the safety of this material has already been questioned in the

past, even leading the US to withdraw implants from the market from 1992 to 2006,

in recent decades, they have been evaluated as safe, inert to the human body, presenting

little or no risk to patients1-3.

However, in recent years, a growing body of evidence has linked IMS to the induction

of immunological and inflammatory effects, including neoplasms such as BIA ALCL (Breast

Implant Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma) lymphoma4, and autoimmune diseases - ASIA syndrome (Autoimmune /Auto-inflammatory Syndrome

Induced by Adjuvants)1.

Studies bring up the discussion that “gel bleeding,” which is the migration of silicone

particles out of the implants even when they are intact, can exert a chronic stimulus

to the immune system, inducing autoimmunity, disorders such as ASIA syndrome, connective

tissue pathologies, allergies, immunodeficiencies, lymphoma and systemic symptoms3,5.

The attempt to establish a cause and effect relationship is complex, especially in

the case of immunological/rheumatic disorders, which are not very prevalent in the

general population and often have a multifactorial etiology1. The topic has been widely studied, often with results that are still inconsistent3,5,6, but that have been sufficient to generate insecurity in patients and the medical

community in general.

As a result, and the widespread dissemination of this topic on social networks in

recent years, we are experiencing a time of growing demand for IMS explants - which

brings the plastic surgeon the challenge of maintaining the design and harmony of

the breasts now in the absence of implants. It is a very delicate and heterogeneous

group of patients, including women who fear having some pathology related to IMS,

to countless others who no longer want implants for other reasons and seek aesthetically

pleasing options. The surgeon must become familiar with the management techniques

of these patients7, which will vary between isolated explants and different mastopexy techniques, both

associated or not with fat grafting.

Fat grafting is a great ally in these cases, being an autologous and safe option to

increase volume and improve breast contour and its local regenerative effects. Fat

grafts were described at the end of the 19th century, but it was from 1980 onwards

that this technique began to gain popularity in plastic surgery8. The graft volume’s limit, or ideal, to achieve an effective and safe result is widely

discussed since excessive volumes in the same surgery will be more subject to necrosis

and complications. In addition, partial graft loss always occurs and has an unpredictable

behavior, making it difficult to see the final surgical result. A wide range of resorption

rates is described in the literature8,9, therefore, patients should be informed about possible asymmetries or irregularities

that may occur in the postoperative period.

Although not mandatory when there is no evidence or previous diagnosis of associated

pathologies, patients frequently request total capsulectomy. There is a fear that

the presence of the residual capsule, possibly impregnated with silicone particles,

or the extravasation of these particles resulting from intracapsular “gel bleeding,”

may cause the maintenance of the chronic inflammatory process and the permanence of

the associated risks. Following this reasoning, en bloc capsulectomy - which consists

of removing the implants with the capsules completely closed in a single piece - would

be the safest option, but it is not always possible.

OBJECTIVE

To demonstrate surgical options for removing silicone breast implants, ranging from

simple explants to explants associated with mastopexy, using fat grafting.

METHODS

In this study, we used 4 surgical strategies:

Isolated explant;

Explant associated with fat grafting;

Mastopexy (with or without inferior pedicle flaps);

Mastopexy associated fat grafting.

The choice of technique is based on variables such as the size of the implants to

be removed, presence of breast sagging/ptosis, residual breast volume after explantation,

lipodystrophy in other areas of the body (availability of the donor area), patient

expectations and acceptance of scars.

This study evaluated 20 patients who underwent silicone breast explants between September

2020 and March 2021. Inclusion criteria were age over 18 years, without phlogistic/inflammatory

signs in the breasts, and with a desire to permanently remove the implant. Exclusion

criteria were presence of mastectomy sequelae with loss of architecture of the breast

region, presence of reconstructions in flaps and grafts; possibility of pregnancy

or puerperium, need for explant due to local infection.

The specific surgical indication for the explant did not come from the medical team

in any case; plastic surgery or rheumatology. It was always the objective and explicit

demand of the patients, motivated by the following complaints (the same patient has

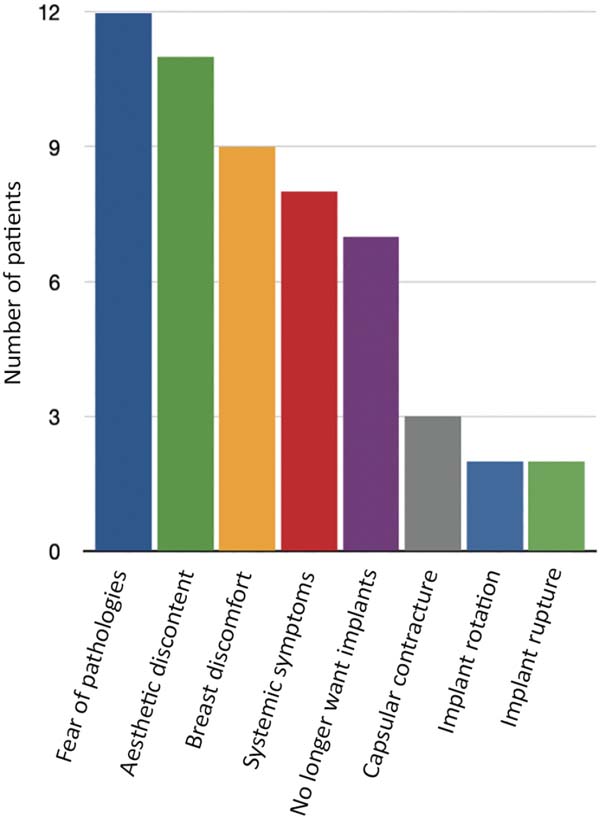

more than one of them) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Complaints presented by patients motivating the desire for the explant.

Figure 1 - Complaints presented by patients motivating the desire for the explant.

- Fear of pathologies associated with IMS (12 patients)

- Aesthetic discontent (11 patients)

- Pain or discomfort in at least one breast (9)

- Systemic symptoms, which patients believed to be related to implants (8 patients)

- Desire to have no more prostheses and no commitment to future exchanges (7 patients)

- Capsular contracture (3 patients)

- Implant rotation (2 patients)

- Implant rupture (2 patients)

This study was carried out with patients followed up in a private clinic in Campinas-SP,

with authorization to disclose data according to the consent form signed by the patients.

All of them were operated on in private hospitals in the same city, in a surgical

center, with general anesthesia, according to the surgical technique described below:

In the case of Simple Explant, the contour of the breast and the area to be fat grafted are marked. The same incision

used to include the prostheses is then used, usually requiring enlargement to 6 cm

(full size). The dissection is carried out through it until the capsule pocket and

then the complete detachment, preferably keeping it closed with the implants. This

step must be followed by rigorous hemostasis, and the placement of drains is not mandatory

but may be necessary. If the flap is not excessively thin and allows it, it is interesting

to close the prosthesis pocket laterally with an absorbable suture, which helps contour

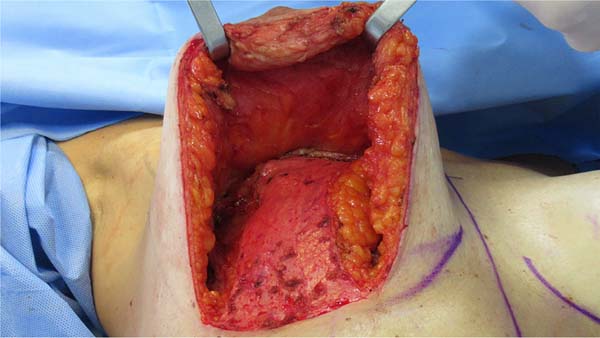

the breast and reduces dead space (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Immediate appearance of breasts after breast explantation.

Figure 2 - Immediate appearance of breasts after breast explantation.

Lipografting: after closing the incision, liposuction is performed using a conventional technique

in a vacuum device, avoiding very large or very thin cannulas - we use 3 mm. This

fat is passed through a centrifuge (Figure 3) and grafted with 2 - 2.5 mm cannulas in crossed tunnels (Figure 4). The tunnels are preferably made in the subcutaneous plane, but they can also be

in the intramuscular plane (pectoralis major muscle) or even in the breast parenchyma9,10. Priority should be given to the region of the upper and medial pole of the breast,

in addition to areas of more pronounced deformities (Figure 5), but the graft must be performed in the breast as a whole in order to obtain a uniform

flap, without distortion of its natural shape (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 3 - Fat grafting after centrifugation.

Figure 3 - Fat grafting after centrifugation.

Figure 4 - Breasts immediately after bilateral explantation. 200 cc fat grafting performed only

on the right breast, showing improvement in contour and projection.

Figure 4 - Breasts immediately after bilateral explantation. 200 cc fat grafting performed only

on the right breast, showing improvement in contour and projection.

Figure 5 - Irregularity of the breast parenchyma causing significant tissue depression immediately

after explantation.

Figure 5 - Irregularity of the breast parenchyma causing significant tissue depression immediately

after explantation.

Figure 6 - Immediate postoperative period, after fat grafting of 190 cc, with significant improvement

of the previous tissue depression and slight projection of the upper pole.

Figure 6 - Immediate postoperative period, after fat grafting of 190 cc, with significant improvement

of the previous tissue depression and slight projection of the upper pole.

Figure 7 - Immediate postoperative period, after fat grafting of 440 cc/side.

Figure 7 - Immediate postoperative period, after fat grafting of 440 cc/side.

In the case of Mastopexy with Explant, marking is performed with points A, B, and C according to Pitanguy’s mammoplasty

marking (Figure 8)11, with a distance of 10 cm from AB/AC BC, depending on the digital clamping. We make

the incision de-epithelializing the entire marked area (Figure 9), then release the upper flap from the nipple-areolar complex and make an inferior

pedicle flap whenever possible and/or necessary (Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 8 - Preoperative scheduling of mastopexy with breast explant.

Figure 8 - Preoperative scheduling of mastopexy with breast explant.

Figure 9 - De-epithelialization of the entire previously marked area.

Figure 9 - De-epithelialization of the entire previously marked area.

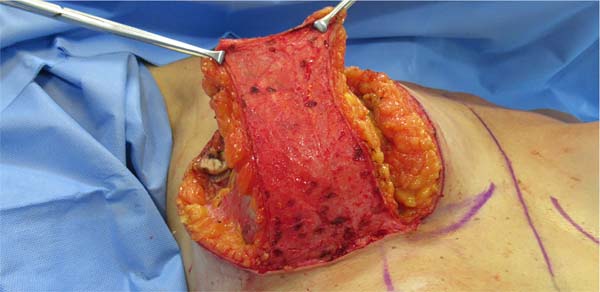

Figure 10 - Confection of inferior pedicle dermocutaneous flap.

Figure 10 - Confection of inferior pedicle dermocutaneous flap.

Figure 11 - A pre-made inferior pedicle dermocutaneous flap and explant with en bloc capsulectomy

in progress.

Figure 11 - A pre-made inferior pedicle dermocutaneous flap and explant with en bloc capsulectomy

in progress.

This flap is similar to that described by Lyacir Ribeiro12, being a de-epithelialized dermo-glandular flap of the inferior pedicle, vascularized

by perforators of the internal mammary - mainly from the sixth intercostal space,

since between the fourth and fifth space it will be detached from the wall chest due

to the presence of implants. It must have a minimum width of 5 cm and helps preserve

as much breast tissue as possible for breast assembly, avoiding resection of tissue

additional to the explant.

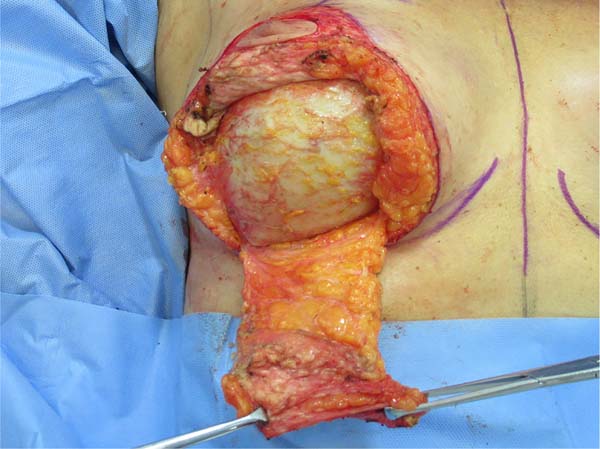

We proceeded with the dissection around the capsule and carried out the explant with

a closed capsule (Figures 12 and 13). Subsequently, this flap will be fixed to the chest wall with a non-absorbable suture,

and the breast will then be mounted on it (Figures 14 and 15). Dermal release from the base of the flap will not be performed to ensure the best

possible vascularization since it is already detached from the chest wall due to the

previous presence of the implant.

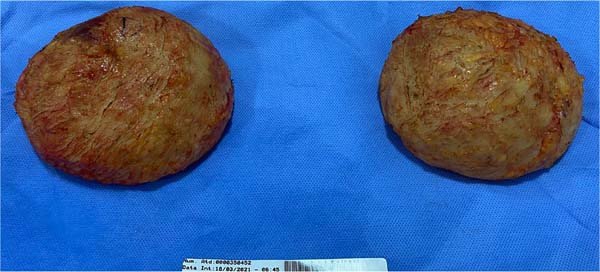

Figure 12 - Silicone implants with total block capsulectomy.

Figure 12 - Silicone implants with total block capsulectomy.

Figure 13 - Empty appearance of breasts after explantation, with thin parenchyma.

Figure 13 - Empty appearance of breasts after explantation, with thin parenchyma.

Figure 14 - Inferior pedicle dermocutaneous flap fixed to the chest wall at the level of the second

intercostal space.

Figure 14 - Inferior pedicle dermocutaneous flap fixed to the chest wall at the level of the second

intercostal space.

Figure 15 - Assembly of the breast over the pedicle, which fills and projects the mammary cone.

Figure 15 - Assembly of the breast over the pedicle, which fills and projects the mammary cone.

After completing the mastopexy, liposuction and fat grafting are performed as described

for cases of simple explantation (Figure 16).

Figure 16 - Immediate post-operative period of mastopexy with removal of 280 cc silicone implants,

with 110 cc of fat grafting in each breast.

Figure 16 - Immediate post-operative period of mastopexy with removal of 280 cc silicone implants,

with 110 cc of fat grafting in each breast.

Postoperatively, a low-compression dressing and surgical mesh are indicated.

RESULTS

Twenty patients undergoing breast explant surgery were evaluated, ranging from 21

to 58 years, with an overall mean age of 36.88 years. Patients had the implants for

periods ranging from 2 to 16 years, with a mean time of 9.7 years.

Of these, 7 patients underwent breast explantation with fat grafting, and 13 underwent

explantation with a mastopexy with or without fat grafting.

In the group in which only explantation and fat grafting were performed (7 patients),

the mean age was 32.28 years. The implants removed ranged from 240 to 375 ml, with

an average volume of 300 ml. Only 1 had submuscular prostheses; the other 6 were subglandular.

The volume of grafted fat varied according to the availability of the donor area,

with a minimum of 100 cc and a maximum of 440 cc per breast, with an average of 242.14

cc. Fat grafting of the maximum volume of viable fat (after centrifugation) obtained

in liposuction was performed.

In the group in which mastopexy was performed (13 patients), the mean age was 39.81

years. In 12 cases, an inferior pedicle dermoglandular flap was made, according to

the technique described. In 1 patient, the flap was not used because it was a very

glandular and voluminous breast, even after explantation, without additional tissue

preservation or fat grafting. In addition to this, 2 other patients chose not to use

the fat graft for various reasons (fear of future fat cysts and no desire for liposuction),

totaling 3 patients who did not undergo fat grafting. Fat grafting was performed to

smooth the post-capsulectomy flap and help contour the breast, not necessarily achieving

a significant increase in breast volume.

Among the mastopexies, the fat graft volume varied from 75 ml to 150 ml per breast,

with an average of 121.42 ml. The implants removed ranged from 155 to 400 ml, with

an average volume of 283 ml. Among these patients, 3 had submuscular implants, and

the other 10 were subglandular.

No patient had a clinical picture or suspected BIA-ALCL. Follow-up with a rheumatologist

was offered and oriented to all who manifested any systemic symptoms, but it was effectively

performed by only 4. No diagnosis of ASIA syndrome has been made so far. Only 1 patient

reported fibromyalgia and Crohn’s disease diagnosis, developed while the implants

were in use and already being followed up at the time of explantation. All capsules

were sent for anatomopathological examination, no significant changes were found.

As complications, we had 2 cases of hematomas among patients who underwent simple

explantation with fat grafting, both in PO1 and related to emesis on short trips after

hospital discharge. One of these cases required surgical re-approach for drainage.

In addition, 1 patient evolved with tiny fatty nodules, with expectant management.

There were no cases of infection, significant dehiscence, seroma, skin necrosis or

nipple-areolar complex. We had no evidence of significant fat necrosis.

No patient has required or opted for reoperation or surgical revision in the late

postoperative period. No cases of irregularity and significant scar retraction were

observed. Fat grafting efficiently prevented them, even in more severe cases, as in

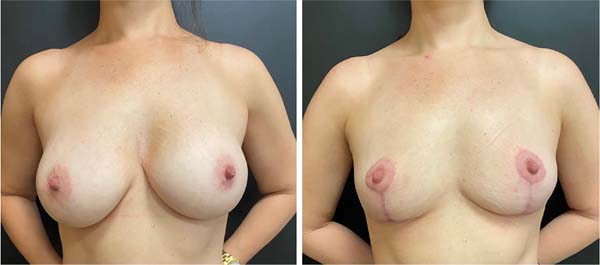

Figure 4, and the patients were generally satisfied (Figures 17 to 19).

Figure 17 - Pre and 50-day postoperative period, after removal of 240 cc subglandular implants

and fat grafting of 200 cc/side.

Figure 17 - Pre and 50-day postoperative period, after removal of 240 cc subglandular implants

and fat grafting of 200 cc/side.

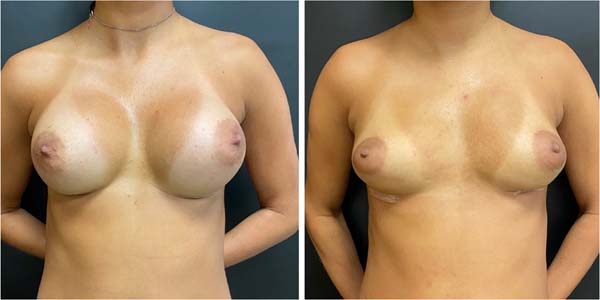

Figure 18 - Pre and 3-month postoperative period of a patient undergoing mastopexy with removal

of 300 cc implants, with fat grafting of 140 cc/side.

Figure 18 - Pre and 3-month postoperative period of a patient undergoing mastopexy with removal

of 300 cc implants, with fat grafting of 140 cc/side.

Figure 19 - Pre and 30 days postoperatively, after removal of 295 and 320 cc implants, and fat

grafting of 110 and 190 cc, respectively. Tissue depression evidenced intraoperatively

satisfactorily corrected.

Figure 19 - Pre and 30 days postoperatively, after removal of 295 and 320 cc implants, and fat

grafting of 110 and 190 cc, respectively. Tissue depression evidenced intraoperatively

satisfactorily corrected.

DISCUSSION

The literature has provided evidence that silicone breast implants can induce local

and systemic reactions. According to these studies, they can trigger a foreign body

reaction characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells and promote the production

of autoantibodies and systemic symptoms, even in asymptomatic patients1.

As mentioned earlier, today’s group of patients seeking breast explant surgery is

heterogeneous. Some patients raise much concern, listing symptoms described on social

media, truly believing they are sickened by the presence of IMS - even without real

suspicion of BIA-ALCL or diagnostic criteria for autoimmune diseases.

On the other hand, many other women deny associated symptoms and do not want the presence

of implants anymore for numerous reasons - aesthetic dissatisfaction, no desire for

exchanges or fear of future complications. Not infrequently, they returned to find

greater beauty in natural and smaller breasts and no longer see sense in prostheses

- which also reflects a trend of change in the standard of beauty prevailing in recent

decades.

In all cases evaluated in this study, the indication of breast explantation came specifically

from the patients who sought medical care with this objective already well established.

The indication of definitive removal did not come from the medical team, whether plastic

surgery or rheumatology and here, only the demand of these patients was met.

With some frequency, they arrive at a consultation dissatisfied, after having already

been evaluated by several medical professionals and having their own symptoms denied,

explant surgery discouraged, and with few alternatives proposed for the removal of

implants without great aesthetic damage - which demonstrates the need for further

discussion of this subject within the specialty.

It takes much tact to manage the cases, both regarding the reception of complaints

and the elucidation of the possibility of a relationship between the symptoms presented

and the presence of implants. Some studies advocate improving up to 60-80% of systemic

symptoms after explantation5,13, but a causal relationship has not yet been established1. It is essential to listen to complaints, but to clarify that there is no scientific

evidence so far that the implant is necessarily their etiology, mainly because they

are symptoms common to other pathologies and even to the current lifestyle - and that

is why they can see no improvement after explantation.

Nesher et al.14 described autoimmune diseases after silicone implant rupture in 4 patients who developed

systemic disorders, resulting in silicone infiltration in lymph nodes and chest wall.

Symptoms in these cases included arthralgia, myalgia, generalized weakness, severe

fatigue, fever, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment, memory loss, irritable bowel

syndrome, and weight loss, which clearly match the criteria for the newly defined

induced autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome by adjuvants (ASIA). The question is whether

such complaints can also be triggered, albeit in a less exuberant setting, by minor

extravasations of the silicone particle, as in the case of “gel bleeding,” justifying

the similar complaints brought by the patients.

The list of possible symptoms frequently cited by patients in consultation is extensive.

In addition to those mentioned above include dryness of the mouth and eyes, tingling

in the limbs, difficulty breathing, acquired food intolerance, breast pain, hair loss,

skin changes, palpitations, excessive sweating, and anxiety. The specialist doctor

must validate such complaints and refer, if necessary, for follow-up in the responsible

specialty - rheumatology. Denying patients’ symptoms, or assuring that there is no

relationship with the IMS, often increases the climate of insecurity and weakens the

relationship between doctor and patient.

As for the surgical strategy, it is important always to align the patient’s expectations

regarding scars, volume, shape, sagging and projection of the breasts during the preoperative

period - with the real and effective technical possibility.

Regarding the fat graft, we emphasize that it does not have the same projection and

contour capacity as an implant and that its main objective is to avoid scar retractions

and irregularities resulting from the explant and, mainly, from the capsulectomy.

It is also important to clarify to patients that the behavior of the fat graft is

not very predictable, that post-procedure partial resorption always happens, and its

proportion depends on numerous factors, which can lead to future asymmetries8,9.

A preferred area for obtaining grafts (liposuction) was not chosen. We had very thin

patients who would not be candidates for liposuction in any other context. We, therefore,

looked for any available regions, the most frequent areas being the abdomen, flanks,

breeches and inner thighs. It is not interesting to start the procedure with liposuction,

as the explant can be laborious and time-consuming, causing the fat to remain in a

bottle for a long time, making subsequent grafting difficult and impairs its viability.

Caution should also be taken concerning the volume used since studies have already

shown that, without external tissue expansion devices (such as the Brava LLC), grafts

greater than 200 ml in the same session present a greater risk of necrosis and lower

integration rate9,15.

Fat grafting is concentrated in the superomedial pole, helping to project the cervix,

but it must be performed on the entire breast to achieve a uniform appearance of the

breast tissue and a rounded contour without distorting the position of the nipple-areolar

complex. Possible complications of fat grafting include irregularities, indurated

areas, persistent pain at the injection site, hematoma, fat necrosis, oily cyst formation

and calcification, local infection8,9,16.

Fat grafts were discouraged in the 1980s due to the possibility of microcalcifications

and oily cysts arising from their use, which could eventually make the diagnosis of

breast neoplasms difficult. Studies from this period showed that such fears were not

justified, and from 2009 onwards, it was understood as safe and became used8 widely. The biggest challenge of this procedure today is the degree of unpredictability

of volume retention of fat grafts after transplantation, and much effort is made to

find techniques that obtain the highest possible integration rate.

Among the patients who underwent only explant with fat grafting, all presented loss

of breast projection and some degree of residual flaccidity. In this group, 1 patient

had a clear indication of associated mastopexy but did not want it for personal reasons

(planning for an upcoming pregnancy). In this group, we always use all the fat made

available by liposuction to obtain the greatest possible final breast volume. In no

case was the fat graft sufficient to return a projection or volume similar to the

prostheses, but it fulfilled its function of avoiding retractions and deformities

and maintaining a satisfactory final volume.

Regarding capsulectomy, we chose to perform it as a priority in total and en bloc

- which consists of removing the implants with the capsules fully closed. We aim to

avoid the “bleeding gel” leakage or even the permanence of capsule fragments possibly

impregnated by the same material. Some studies suggest that these silicone particles

can stimulate the immune system, inducing or perpetuating systemic symptoms and associated

pathologies3,5, and therefore, to date, we cannot guarantee the safety of this material for all

patients. As this is a specific group of women already with complaints and symptoms

possibly related to IMS, we opted for a more comprehensive approach - although this

may increase the technical difficulty and surgical morbidity.

However, even in the preoperative period, it is emphasized that although total and

en bloc capsulectomy is an objective, it is not always feasible. Very thin capsules

often break during detachment and can be removed completely, but not en bloc. In addition,

submuscular prostheses generally have the posterior wall of the capsule tightly adhered

to the ribs, making the procedure impossible or offering an increased risk of injury

to adjacent noble structures - which is not justified when there is no evidence of

associated pathologies, such as lymphoma.

In these cases, capsulectomy may not be total or en bloc. In cases of mastopexy, the

use of the inferior pedicle dermoglandular flap is interesting to assist in the assembly

of this breast, which tends to be quite emptied after explantation, as shown in Figure 13. The technique is similar to that described by other authors12,17-19, but here we performed total capsulectomy - which makes the flap more fragile from

the vascular point of view since it is detached from the chest wall due to the previous

presence of the prosthesis. For this reason, we do not incise the dermis at its base

and carefully assess its feasibility.

As for criticisms of this work, we know that the casuistry and the follow-up time

are small, which impairs the evaluation and final validation of these techniques.

However, they have proved safe, easy to reproduce and provide a high degree of satisfaction

among patients.

CONCLUSION

The demand for breast explants is legitimate, regardless of whether or not it is associated

with implant-related pathologies. It is essential that we are attentive to possible

symptoms and well trained to offer adequate surgical options, keeping the breasts

with a preserved and harmonious shape, even with the loss of volume and projection.

Both simple breast explantation techniques and mastopexy, associated with fat grafting,

can return the breast to an aesthetically pleasing shape with low complication rates.

| COLLABORATIONS |

| BBA |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization,

Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization

of operations and/or trials, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing

- Review & Editing.

|

| ILC |

Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing. |

1. Private Clinic, Campinas, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Bruna Borghese Augustini, Rua Fernão Lopes, nº 1.067 - Parque Taquaral, Campinas, SP, Brazil Zip Code 13087-050,

E-mail: bruborghese@gmail.com