Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Cultural adaptation of the blepharoplasty outcomes evaluation questionnarie: Blepharoplasty Outcomes Evaluation

Adaptação cultural do questionário de avaliação de resultados em blefaroplastia: Blepharoplasty Outcomes Evaluation

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The use of quality of life questionnaires has proved to be very useful in giving greater objectivity to evaluating treatment results. The internationalization of these instruments, in turn, allows for interpopulation comparison but requires a specific methodology in order not to cause distortions due to failures in translation or cultural differences. The Blepharoplasty Outcomes Evaluation questionnaire, in English, is a simple application tool with objective questions with a good application for this purpose. The questionnaire has already been tested for reliability, validity and responsiveness.

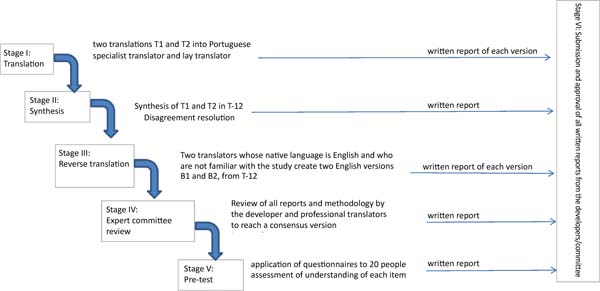

Methods: According to the methodology proposed by Beaton et al., translation and cultural adaptation into Portuguese was performed with 5 stages. Stage 1 - translation by two native Portuguese-speaking translators. Stage 2 - preparation of the synthesis version. Stage 3 - reverse translation by two native English-speaking translators. Stage 4 - review by an evaluation committee. Stage 5 - application to a population of 20 people.

Results: There were no comprehension problems for the final population from the evaluation committee.

Conclusion: The questionnaire was successfully translated and adapted.

Keywords: Translational medical research; Evaluation of health care outcomes; Blepharoplasty; Surveys and questionnaires; Face; Treatment result.

RESUMO

Introdução: O emprego de questionários de qualidade de vida tem se mostrado muito útil no sentido de dar maior objetividade à avaliação de resultados de tratamentos. A internacionalização desses instrumentos, por sua vez, permite a comparação interpopulacional, mas requer uma metodologia específica, a fim de não causar distorções devido a falhas na tradução ou a diferenças culturais. O questionário Blepharoplasty Outcomes Evaluation, de língua inglesa, é uma ferramenta de simples aplicação, com perguntas objetivas com boa aplicação para esse fim. O questionário já foi testado em relação à sua confiabilidade, validade e capacidade de resposta.

Métodos: Realizada tradução e adaptação cultural para a língua portuguesa, segundo a metodologia proposta por Beaton et al., na qual existem 5 estágios. Estágio 1 - tradução por meio de dois tradutores nativos de língua portuguesa. Estágio 2 - confecção de versão de síntese. Estágio 3 - tradução reversa por dois tradutores nativos de língua inglesa. Estágio 4 - revisão por um comitê avaliador. Estágio 5 - aplicação a uma população de 20 pessoas.

Resultados: A partir do comitê avaliador, não houve problemas de compreensão para a população final.

Conclusão: O questionário foi traduzido e adaptado com sucesso.

Palavras-chave: Pesquisa médica translacional; Avaliação de resultados (cuidados de saúde); Blefaroplastia; Inquéritos e questionários; Face; Resultado do tratamento

INTRODUCTION

The search for greater objectivity in evaluating treatment results is necessary to improve the levels of evidence, especially in plastic surgery, whose main objective is subjective, to improve quality of life (QoL)1.

In the literature, it is clear that the mechanisms for objective measurement of results in cosmetic procedures are still in their infancy, but they point to a tendency to use tools to measure results reported by patients themselves (PROM or PRO) through questionnaires2. Fortunately, there are already great advances in this area, with the publication of several articles proposing questionnaire models3,4.

The Breast-Q, Face-Q and Satisfaction with Facial Appearance Scale and Skindex tools, for example, have gone through a rigorous validation process and are fully compliant with US Department of Drug Control (FDA) acceptance requirements, and they stand out, together with Skindex, concerning the other PROMs, according to Morley et al.2,3.

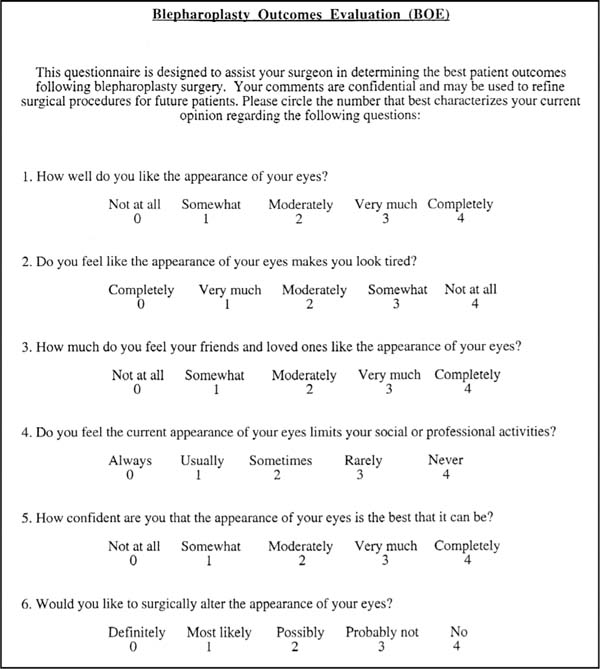

Kosowski et al.4 found 442 articles evaluating results in aesthetic, surgical or non-surgical procedures. Among these, 47 were specific for facial appearance, but only 9 met the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. None of them satisfied all the guidelines. All tools proved to be limited, either by their development, validation, or content. In the same study, only the Blepharoplasty Outcomes Evaluation (BOE) was specific for blepharoplasty4.

The BOE was described by Alsarraf et al., along with other questionnaires in English specific to skin rejuvenation and facial procedures (Skin Rejuvenation Outcome Evaluation - SROE), rhinoplasty (Rhinoplasty Outcome Evaluation or ROE) and rhytidectomy (Facelift Outcome Evaluation - FOE). )5,6.

Such questionnaires address the physical, mental and social aspects necessary for a good evaluation.3.4. The BOE questionnaire was tested regarding its validity, reliability and responsiveness presented as a reliable quantitative tool for measuring results2,5,7.

The internationalization of these questionnaires, in turn, allows the comparison of treatment results between different populations. However, some care must be taken so that there are no distortions due to failures in translation or cultural differences that alter the results of the questions, per se. This would decrease the interpopulation comparative value8,9. Of the four Alsarraf questionnaires, the ROE (Rhinoplasty Outcome Evaluation), the FOE (Facelift Outcome Evaluation), and the SROE (Skin Rejuvenation Outcome Evaluation)10 had already been translated into Portuguese, leaving only the BOE (Blepharoplasty Outcome Evaluation) to which this study refers11.

The BOE is composed of six questions (Annex 1). Each answer can be graded from 0 (least satisfied possible) to 4 (most satisfied possible). The marked values must be added, divided by 24 and multiplied by 100, to obtain a score from 0 to 100, with 0 being the least satisfied possible and 100 being the most satisfied possible6.

Such an instrument can be very useful for developing scientific studies and for the follow-up of results by plastic surgeons.

Thus, the objective of the present study is to translate and culturally adapt the BOE questionnaire into Brazilian Portuguese.

OBJECTIVE

Translate and culturally adapt the Blepharoplasty Outcome Evaluation (BOE) questionnaire to Brazilian Portuguese.

METHODS

The study was authorized by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Ceará, under protocol number 33290513.8.0000.5589, and performed in a private clinic in 2019.

The BOE questionnaire was translated and culturally adapted to Brazilian Portuguese according to the methodology proposed by Guillemin et al.12. This methodology consists of five stages (Figure 2) and is accepted in the literature for translating several other instruments8.

Translation

Stage 1 the questionnaire was submitted to two translations (T1 & T2) from English to Portuguese. One of them was performed by a lay translator and the other by a plastic surgeon translator, with experience in the procedure, as recommended in the literature.

Stage 2 (Synthesis): The T1 and T2 Portuguese versions of the questionnaires were evaluated by both Stage 1 translators. The translators discussed the differences between their versions and developed a consensual version called T-12.

Stage 3 (Reverse translation): the T-12 questionnaire was submitted to two lay translators unaware of each other or the current study, whose native language was English.

Stage 4 (Submission to an expert committee): a medical board with knowledge in the area was asked to monitor the process, evaluate the versions, pointing out inconsistencies and deviations. This board was composed of a dermatologist, a general surgeon and an orthopedist.

There was pacification, through discussions, on four points:

Semantic equivalence. The translations were evaluated regarding the preservation of their meaning, the possibility of multiple meanings, and the existence of grammatical difficulties.

Idiomatic equivalence. Expressions or colloquialisms are difficult to translate. The committee sought the presence of these expressions and equivalents in Portuguese.

Experimental equivalence. The questioned experiences were evaluated as to their existence in the Portuguese language.

Conceptual equivalence. The expressions must contain the same concept. For example, when talking about family, in some cultures, it means the closest small family nucleus, and others include all relatives.

Cultural adaptation

Stage 5 - (Pre-final version testing). A pre-test with the final T-12 version was carried out with a sample of 20 people. This group was composed of dermatofunctional physiotherapy graduate students. Each participant completed the questionnaire and was interviewed by the researcher to point out possible inconsistencies and difficulties in understanding.

Stage 6 - Submission of documentation to the expert committee to verify the translation process.

RESULTS

The BOE questionnaire was translated into T1 and T2 versions. There were some points of divergence between the two versions, but a consensus was reached with the T-12 version.

This version was subjected to two reverse translations, B1 and B2, which presented some divergences without changing the original meaning.

Versions B1 and B2 were analyzed by the author of the original questionnaires, contacted by email, who did not identify any change in meaning or inconsistency between the questionnaire translated from Portuguese into English and its original version.

There were no difficulties concerning filling in and understanding the questionnaires.

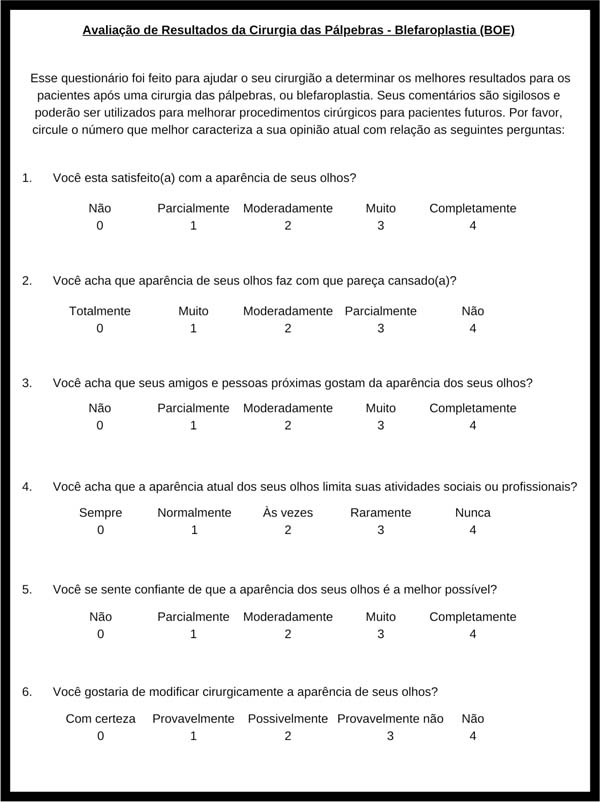

The committee evaluated all translation process steps and contributed with suggestions for changes, which were accepted. As a result, the final result of the translation was as shown in Annex 2.

DISCUSSION

There were no major difficulties translating the questionnaires due to the small number of expressions with no known translation into Portuguese.

We believe that quality of life questionnaires are important to make some subjective parameters more objective and comparable. This allows results to be compared, providing better levels of evidence in an area of knowledge that lacks it. However, there is still no perfect questionnaire.

Comparing tools is outside the scope of this study. However, although the BOE questionnaire has statistically shown its validity, reliability and responsiveness, its design does not seem to be as well-founded as that of the Face-Q, which provides a significant interval level. This allows the construction of defined units with a uniform distance between them. This means, for example, that if a person progressed from a score of 100 to a score of 120, there was an increase similar to that of another person who progressed from a score of 120 to a score of 140, which is not true for most other instruments13.

On the other hand, unlike the Face-Q, the BOE is a specific questionnaire for blepharoplasty, publicly and freely available, which facilitated its translation. Its application takes less than 1 minute.

Other shortcomings of the BOE are that there are still no cut-off points and levels of normality, even in its original language, which we suggest for future studies.

CONCLUSION

Considering the methodology applied, we concluded that the translation of the BOE questionnaire (Figure 3) is suitable for use in Brazilian Portuguese.

REFERENCES

1. Ferreira MC. Cirurgia plástica estética: avaliação dos resultados. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2000;15(1):55-61.

2. Morley D, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R; Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Group, Oxford. A structured review of patient-reported outcome measures used in cosmetic surgical procedures. Report to Department of Health, 2013. Oxford: University of Oxford; 2013.

3. Mackintosh A, Gibbons E, Casañas i Comabella C, Fitzpatrick R; Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Group, Oxford. A structured review of patient-reported outcome measures used in elective procedures for coronary revascularisation. Report to Department of Health, 2010. Oxford: University of Oxford; 2010.

4. Kosowski TR, McCarthy C, Reavey PL, Scott AM, Wilkins EG, Cano SJ, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures after facial cosmetic surgery and/or nonsurgical facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(6):1819-27.

5. Alsarraf R, Larrabee WF Jr, Anderson S, Murakami CS, Johnson CM Jr. Measuring cosmetic facial plastic surgery outcomes: a pilot study. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3(3):198-201.

6. Alsarraf R. Outcomes research in facial plastic surgery: a review and new directions. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24(3):192-7.

7. Alsarraf R. Outcomes instruments in facial plastic surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2002;18(2):77-86.

8. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-91.

9. Ferreira LF. Tradução para a língua portuguesa, adaptação cultural e validação do Breast Evaluation Questionnaire [Dissertação]. São Paulo: Universidade Federal de São Paulo; 2009.

10. Furlani EAT, Saboia DB, Costa MLM. Adaptação cultural do questionário de avaliação de resultados em rejuvenescimento de pele (Skin Rejuvenation Outcome Evaluation - SROE). Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2020;35(4):402-7.

11. Furlani EAT. Adaptação cultural do questionário de avaliação de resultados em ritidoplastia: facial outcome evaluation. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(3):501-5.

12. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(12):1417-32.

13. Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Cano SJ. Development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q satisfaction with appearance scale: a new patient-reported outcome instrument for facial aesthetics patients. Clin Plast Surg. 2013;40(2):249-60.

1. Eduardo Furlani Clinic, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

| COLLABORATIONS | |

|---|---|

| EATF | Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing. |

| DBS | Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing. |

| MLMC | Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing. |

| MVAB | Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing. |

Corresponding author: Eduardo Antonio Torres Furlani, Rua Barbosa de Freitas, 1990, Aldeota Fortaleza, CE, Brazil, Zip Code 60170-021, E-mail: eduardo@eduardofurlani.com.br

Article received: March 16, 2021.

Article accepted: July 14, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter