Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Temporal lift with repositioning of the orbicular muscle and eyebrow tail

Lift temporal com reposicionamento do músculo orbicular e da cauda da sobrancelha

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) is the best structure we have at our disposal to elevate and reposition the face and neck in the facelift. However, in the temporoorbital region, this structure is often neglected. In the search for a simple, efficient and safe solution to treat temporoorbital droop, the author describes a temporal lift tactic with eyebrow tail repositioning to treat aging and sagging of the temporoorbital region.

Methods: Treatment was performed in 358 patients between 2017 and 2020 in complete or temporary lifts. Only 30 were included in the article because they were exclusively submitted to temporal lifts, with or without blepharoplasty. Through a broken marginal intracapillary incision in the temporal region and with supraSMAS detachment, musculoaponeurotic treatment of the orbitotemporal region was performed, in addition to excess skin resection.

Results: The tactic presented was efficient in lifting and opening the tail of the eyebrows in all treated cases, in addition to the effect of loss of contractile function of the lateral portion of the orbicularis muscle, with a significant improvement in periorbital wrinkles and orbitotemporal sagging.

Conclusion: The effectiveness and excellent results achieved with the described operative tactic, associated with the scarcity of isolated or specific treatment options for the orbitotemporal region, make the proposed temporoorbital lift an excellent alternative for the rejuvenation of this region.

Keywords: Face; Rhytidectomy; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Eyebrows; Superficial musculoaponeurotic system.

RESUMO

Introdução: O sistema musculoaponeurótico superficial (SMAS) é a melhor estrutura que temos à nossa disposição para elevar e reposicionar a face e o pescoço no face lift. No entanto, na região têmporo-orbitária, esta estrutura é frequentemente negligenciada. Na busca por uma solução de execução simples, eficiente e segura para tratar a queda têmporo-orbitária, o autor descreve uma tática de lift temporal com reposicionamento da cauda das sobrancelhas para tratamento do envelhecimento e flacidez da região têmporo-orbitária.

Métodos: Foi realizado o tratamento em 358 pacientes entre 2017 e 2020, em lifts completos ou apenas temporais. Destes, apenas 30 foram incluídos no artigo por terem sido submetidos exclusivamente a lifts temporais, acompanhados ou não de blefaroplastias. Através de incisão intracapilar marginal quebrada em região temporal e com descolamento supraSMAS, foi realizado tratamento musculoaponeurótico da região órbito-temporal, além de ressecção da pele em excesso.

Resultados: A tática apresentada foi eficiente na elevação e na abertura da cauda das sobrancelhas em todos os casos tratados, além do efeito de perda da função contrátil da porção lateral do músculo orbicular, com melhora significativa das rugas periorbitais e da flacidez órbito-temporal.

Conclusão: A eficácia e os ótimos resultados alcançados com a tática operatória descrita, associada à escassez de opções de tratamento isolado ou específico da região órbito-temporal, tornam o lift têmporo-orbitário proposto uma excelente alternativa para o rejuvenescimento desta região.

Palavras-chave: Face; Ritidoplastia; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Sobrancelhas; Sistema musculoaponeurótico superficial

INTRODUCTION

The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) is considered the main focus in the surgical treatment of facial aging1-6. After the work of Mitz &Peyroniein 19767, dissection of the SMAS became increasingly popular, with the adoption of different ways of tensioning it since then8-10. It is a fibromuscular fabric composed of several layers divided to envelop the superficial mimetic musculature. It becomes the best structure we have at our disposal to, safely and naturally, achieve the elevation and repositioning of the face the neck. It has a variable thickness, being thinner and discontinuous in the anterior region of the cheek and thicker and more uniform in the masseteric-parotid and temporoparietal regions of the forehead, where it is called temporoparietal fascia6,7.

From a functional point of view, the SMAS acts as a distributor and amplifier of facial muscle activity, and, for rejuvenation, the ideal is that we can pull and increase the tension of the largest possible area of this structure without forgetting the temporoorbital region7,8.

Even in the 1980s, Pitanguy2,10, Baker11 and many others dissected the lateral SMAS that directly covers the parotid gland. This procedure of elevation and traction of the lateral superficial fascia was often disappointing, as it produced results similar to those of a simple SMAS plication. In the 1990s, deep dissection and extended procedures such as the deep plane12, the subperiosteal13 and the compound lift14 were the focus.

Almost all tractions are mainly focused on the pre-masseteric and submandibular regions1-6; however, the discussion continues to the present day about what would be the best way to traction the SMAS. The temporoorbital region (including the tail of the eyebrows) is often neglected during conventional (non-videoendoscopic) facelifts.

Most patients who are candidates for a facelift or just a blepharoplasty have evident signs of descent in the lateral region of the orbit and require vigorous repositioning. In this location, the SMAS (temporoparietal fascia) involves the orbicularis and zygomatic muscles and often presents significant mobility, requiring tensioning and repositioning together with the tail of the eyebrows7-9.

We must also consider that the facelift of the lower third, when performed, elevates a large excess of skin to the temporoorbital region, which added to the pre-existing dermomuscular redundancy in the lateral corner of the orbit, aggravates the problem at the site5,10.

In the search for a simple, efficient and safe solution to treat the temporoorbital and eyebrow tail droop, since August 2017, the author has been performing a temporoorbital lift tactic with repositioning of the orbicularis muscle and the tail of the eyebrows that will be described below.

OBJECTIVE

To present a temporoorbital lift tactic with repositioning of the orbicularis and the tail of the eyebrows for the treatment of aging and sagging of the orbitotemporal region, easily reproducible, simple, safe and efficient.

METHODS

In August 2017, the author started using the tactic described here in complete facelifts and, observing its efficiency, from the following month, it started to adopt it in exclusively temporal lifts. Between September 2017 and October 2020, this treatment was performed in 358 patients. Of these, only 30 were included in the study, as they were the ones who underwent exclusively temporal lifts to treat only alterations in the temporoorbital region, whether or not accompanied by blepharoplasty. The main exclusion criteria in the analysis were patients undergoing complete facelifts. The criterion sought to prevent the treatment of the lower third of the face from influencing the occurrence of complications and our perception of the results in the temporal area.

Of the 30 patients analyzed, 27 were female (90%), and three were male (10%). Five underwent temporal lift only (16.6%), and 25 underwent temporal lift accompanied by blepharoplasties (83.4%). The inclusion criteria encompassed patients who did not complain or did not present significant signs of sagging and drooping of the lower third of the face, candidates or not for blepharoplasty, and who presented one or more of the following signs:

All cases analyzed were conducted at the Fibonacci plastic surgery clinic in Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, between September 2017 and October 2020.

The analysis of medical records took place between December 2020 and March 2021. The elaboration of the article followed the Helsinki principles.

Description of the operative tactic: temporal lift

Temporal incisions are made, always intrapilose marginal, in “W”15 and beveled to preserve the follicles on edge. They ranged from 5.0 to 7.5 cm in length, depending on the degree of elevation intended to be achieved in the tail of the eyebrows. Lower eyebrows require more cephalad elevation and therefore require longer temporal incisions, often reaching the tip of the temporal hairy implantation peninsula.

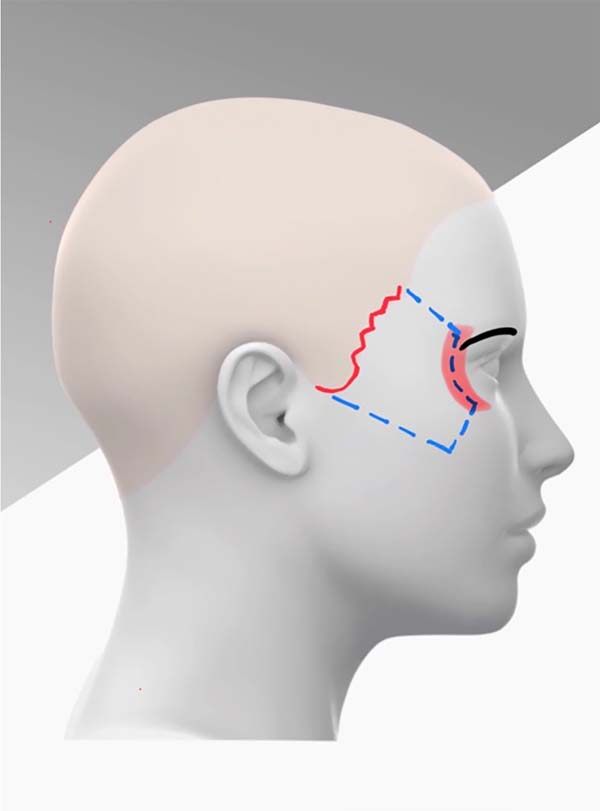

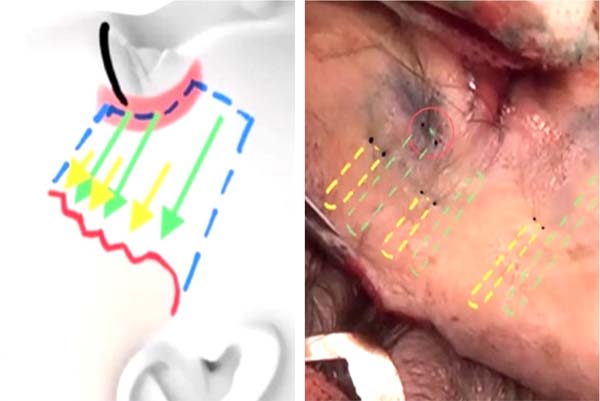

Then, subcutaneous detachment is performed up to approximately 1 cm from the orbital rim, with the upper limit being the tail end of the eyebrow and the lower limit being the most prominent area of the malar region. In this way, we were able to expose a good part of the temporoparietal fascia, the orbicularis muscle in its lateral portion and part of the subcutaneous tissue of the malar region (Figure 1).

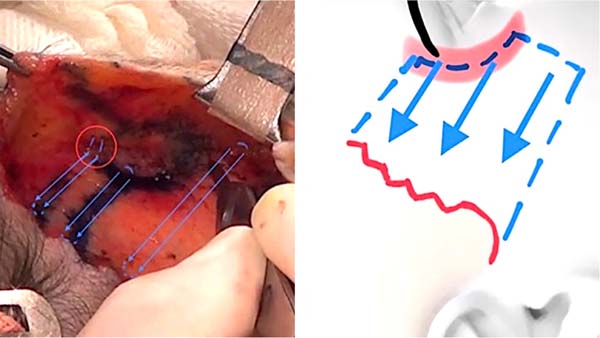

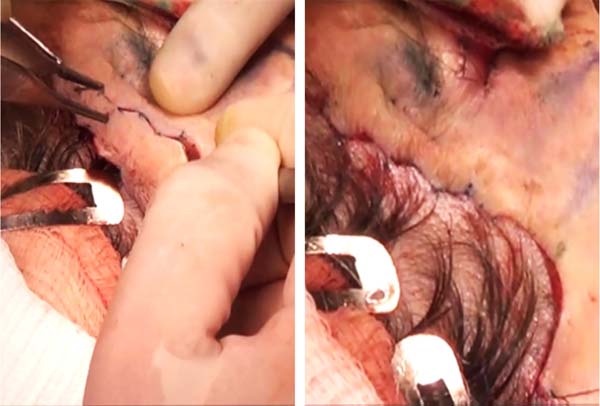

The detachment is performed superficially to the superficial temporal fascia to avoid damage to the temporal nerve. Whenever electrocautery is used, the fascia is elevated with the aid of tweezers and the area is irrigated with saline for the same purpose. After hemostasis, two sutures are performed that pull the orbicularis muscle. The first rests close to the temporal prepilous incision at its cephalic limit, transfixing the temporoparietal fascia and the deep temporal fascia to then encompass, at a distance, the orbicularis muscle in the most cephalic portion of the detachment and the adjacent dermis, in the eyebrow tail region (Figure 2).

In order to achieve adequate traction of the dermis, a considerable amount of the dermis was included, without the thread being visible on the skin surface (Figure 2). This first traction suture is made with Vicryl 5-0 because, as it encompasses the dermis, it causes a large depression in the transfixed area and, as the thread is absorbed, it gradually disappears.

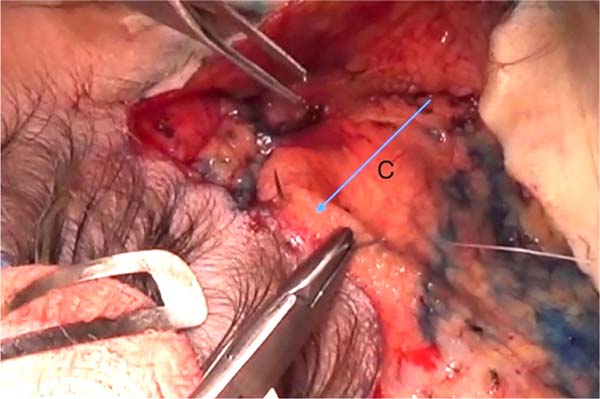

The second traction suture also rests close to the temporal prepilous incision, just below the first, also deep to ensure secure support for traction. Then it also encompasses, at a distance, the orbicularis muscle at the level of the lateral corner of the eyelid and the passage through the muscle is done in two steps (round trip) to avoid fraying. In this traction, the dermis is spared, and we traction only the muscle. As there is no skin pinching, non-absorbable colorless Nylon 4-0 thread is used to achieve vigorous and permanent traction (Figure 2).

These first two traction wires cross the temporal region parallel and with about 1 to 1.5 cm of distance between them. The traction direction of both is always superolateral oblique, but with the degree of inclination varying according to the needs of each case.

Likewise, a third traction suture is placed close to the temporal incision, but now in its caudal portion and also seeking to include the deep temporal fascia. It then encompasses, at a distance, the SMAS and the malar fat at the end of its detachment. As with the suture described above, a double pass is performed using a 4-0 colorless Nylon thread (Figure 3).

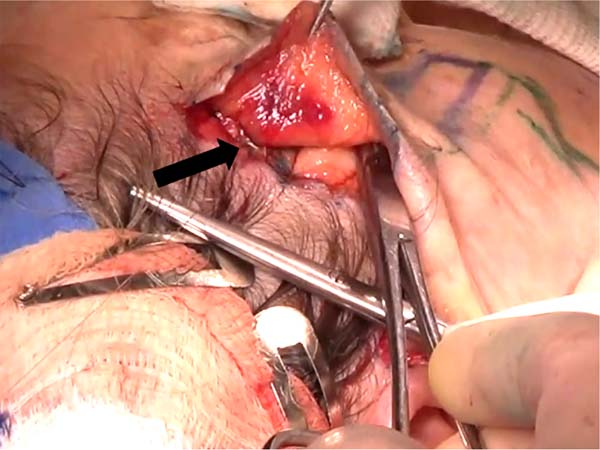

To achieve a decrease in dead space and, at the same time, uniform distribution of skin traction, after the three musculoaponeurotic traction sutures, three skin traction sutures are made in the detached area. All pull exclusively on the dermis and rely deeply on the edge of the temporal incision, occupying the space between the muscle tractions (Figure 4). The three dermal transfixations are performed halfway between the temporal incision and the end of the detachment. Here, a faster absorption thread, Monocryl 5-0, is used, as there will also be pinching of the skin, which will gradually disappear (Figure 5).

After all the traction/adhesion sutures, the excess skin becomes evident, and, without any traction, its resection is performed, mirroring the same design of the temporal incision made previously. The author opts for Gillies sutures with zero tension throughout the closure. Half of them are removed on the sixth postoperative day and the other half on the ninth postoperative day (Figure 6).

RESULTS

What most calls attention to this treatment is the efficiency and durability of the elevation and, mainly, the lateral opening of the eyebrows tail in all treated cases. The increase in the distance between the tail end of the eyebrows and the lateral corner of the eyelids is evident and always significant (Figures 7 and 8).

In addition, a second beneficial and unexpected effect, but always achieved, is the loss or great decrease of the contractile function of the orbicularis muscle in its lateral portion (the region where it is tractioned), with great improvement of the wrinkles called “crow’s feet.” (Figures 9 to 11).

None of the 30 treated cases had complications such as hematomas, paresis, paralysis or necrosis, and all final discharge and postoperative photographs were performed six months after the operation.

DISCUSSION

Much is still discussed about the efficiency of the different ways of traction of the SMAS, and most of the time, the focus of the discussions is the pre-masseteric and mandibular regions. The temporoorbital region and tail of the eyebrows are often neglected in non-videoendoscopic facelifts. The author attributes this to the fact that few truly effective options are described for treating SMAS in this region.

Many patients with an indication for facelift or blepharoplasty have evident signs of sagging and aging in the lateral region of the orbit, including the tail of the eyebrows. All of these will require region-specific treatment16 and, in these cases, the SMAS (temporoparietal fascia/orbicularis muscle in its lateral portion) will often present ample mobility and require aggressive tensioning and repositioning together with the tail of the eyebrows. In addition, large excess skin from the lower half of the face and neck in full facelifts will accumulate in the same temporoorbital region that already has significant dermomuscular redundancy, aggravating the local problem.

The proposed temporoorbital lift is intended to treat, in a simple, effective, and highly reproducible way, sagging and aging of the lateral region of the orbit, which may or may not be associated with a complete facelift and blepharoplasty.

Many years ago, the author chose to use temporal marginal intrapilous incisions in “W” in all complete or partial facelifts he performs. It is a minimally intrapilous incision, where about two rows of hairs are sacrificed to make sure that it will be camouflaged by hairs that will be very close to the margin of the incision that, in the end, after the resection of excess skin, it becomes pre-pilose. To ensure the integrity of the bulbs of these edge wires, the incisions are made in a bevel. In this way, the scar generally has an excellent quality, and we can avoid what the author believes to be the worst of the sequelae in the temporal region: the retreat of the anterior line of hairy implantation with consequent enlargement of the temporal region17 (Figure 12).

The variation in the length of the temporal incision and the angle of the musculoaponeurotic traction sutures allow us to reposition the tail of the eyebrows and the entire temporoorbital drop according to the needs of each case.

In cases with malar bags or festoons, lateral oblique tractions of the lateral border of the orbicularis muscle, associated with vigorous cephalic traction of the orbicularis covering the SOOF (through a lower blepharoplasty) achieve excellent results. In the author’s view, these tractions have become the best treatment option for these deformities (Figure 7) and greatly contribute to the result of blepharoplasty in general.

Another extremely beneficial effect of this approach is that, with the traction of the orbicularis muscles, we can definitively inactivate their contraction in the lateral portion without running the risk of muscle resections at the site18. This effect significantly reduces wrinkles called “crow’s feet,” simulating the effect of botulinum toxin. (Figures 10 and 11)19.

In addition to being an excellent alternative to treat temporoorbital sagging in exclusively temporal lifts, this treatment has also been used in more than 300 complete lifts (which included the lower third of the face), with excellent results.

Among the open approaches for treating the temporoorbital region17, there are other proposals for broken incisions (Connell)15, for releasing the orbicularis muscle with its transverse bipartition and lateral traction (Aston)20 and others for myectomy21,22 with or without fat grafts (Viterbo)18. In 2013, Bozola & Vieira proposed treating the temporal region using a marginal intracapillary incision and temporal detachment in the subcutaneous plane to the lateral half of the orbicularis muscle, followed by fan traction17.

The author’s approach has several similarities with the Bozola technique and some important differences, as described below:

Broken temporal incision in “W.”

Orbicularis traction performed at a distance, which reduces the chance of injury to the frontal branch of the facial nerve, as it prevents the plication from being performed directly on the nerve path. It also allows us to have deep and secure support for the traction by supporting it in the deep temporal fascia, very close to the edge of the temporal incision.

Traction of the dermis of the eyebrow’s tail and the underlying orbicularis muscle make the repositioning of this area very efficient and makes the fibrosis of each leaflet help the other maintain the final higher position both.

Traction of the malar SMAS which, in many patients, achieves a significant mobilization of the middle third and causes more redundancy of the orbicularis muscle in its lateral portion, which the two upper traction sutures will treat.

CONCLUSION

The search for excellence in treating aging in all face sectors makes it necessary to constantly search for new tactics and operative techniques that involve facelift. The few really efficient options for specific treatment of the temporoorbital region and the excellent results achieved with the operative tactic described make the proposed temporoorbital lift an excellent option in treating this region. It is a safe, simple and effective way to treat sagging and aging of the lateral region of the orbit, whether or not associated with lower third lift and blepharoplasty. The success obtained with this approach in the first patients led the author to start using it in absolutely all of our facelift cases, whether complete or only temporary.

REFERENCES

1. Pontes R. O Universo da Ritidoplastia. Rio de Janeiro. Revinter; 2011.

2. Pitanguy I, Radwanski HN, Amorim NFG. Treatment of the Aging Face Using the “Round-lifting” Technique. Aesthet Surg J. 1999;19(3):216-22.

3. Castro CC. Ritidoplastia: arte e ciência. 1ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: DiLivros; 2007.

4. Rohrich RJ, Narasimhan K. Long-Term Results in Face Lifting: Observational Results and Evolution of Technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(1):97-108.

5. Cló TCT, Flávio WF, Leão CEG, Cló FX, Lacerda LM, Leão LR. Sistematização perioperatória para prevenção de hematomas em face-lifts: abordagem pessoal após 1138 casos operados. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34(1):2-9.

6. Warren RJ, Neligan P. Cirurgia Plástica Estética. 3ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier; 2015. p. 184-207.

7. Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(1):80-8.

8. Narasimhan K, Stuzin JM, Rohrich RJ. Five-step neck lift: integrating anatomy with clinical practice to optimize results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(2):339-50.

9. Pelle-Ceravolo M, Angelini M, Silvi E. Complete Platysma Transection in Neck Rejuvenation: A Critical Appraisal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(4):781-91.

10. Pitanguy I, Ramos H, Garcia LC. Filosofia, técnica e complicações das ritidectomias através da observação e análise de 2600 casos pessoais consecutivos. Rev Bras Cir. 1972;62:277-86.

11. Baker TJ, Gordon HI. The temporal face lift (“mini-lift”). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;47(4):313-5.

12. Hamra ST. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86(1):53-61.

13. Ramirez OM. The subperiosteal rhytidectomy: the third-generation face-lift. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;28(3):218-32.

14. Hamra ST. Composite rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90(1):1-13.

15. Connell BF, Marten TJ. Surgical correction of the crow’s feet deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20(2):295-302.

16. Castro CC, Aboudib JHC, Giaquinto MGC, Moreira MBL. Avaliação sobre resultados tardios em ritidoplastia. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2005;20(2):124-6.

17. Bozola AR, Vieira R. Ritidoplastia setorial temporal - incisão marginal intracapilar tração do músculo orbicular e blefaroplastia. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(4):557-62.

18. Viterbo F. New treatment for crow’s feet wrinkles by vertical myectomy of the lateral orbicularis oculi. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(1):275-9.

19. Cabbabe SW, Andrades P, Vasconez LO. Lateral orbicularis oculi muscle plasty in conjunction with face lifting for periorbital rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(4):1285-93.

20. Aston SJ. Orbicularis oculi muscle flaps: a technique to reduce crows feet and lateral canthal skin folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;65(2):206-16.

21. de Assis Montenegro Cido Carvalho F, Vieira da Silva V Jr, Moreira AA, Viana FO. Definitive treatment for crow’s feet wrinkles by total myectomy of the lateral Orbicularis Oculi. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32(5):779-82.

22. Furnas DW. The orbicularis oculi muscle. Management in blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1981;8(4):687-715.

1. Fibonacci Cirurgia Plástica, Plastic Surgery, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

2. Hospital Felício Rocho, Plastic Surgery, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

| COLLABORATIONS | |

|---|---|

| TCTC | Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Realization of operations and/or trials, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation |

| WFFJ | Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft Preparation |

| FXC | Analysis and/or data interpretation, Writing - Review & Editing |

| GVCR | Analysis and/or data interpretation, Formal Analysis, Project Administration |

Corresponding author: Ticiano Cesar Teixeira Cló, Rua República Argentina, 507, Bairro Sion, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Zip Code 30315-490, E-mail: ticianoclo@gmail.com

Article received: March 19, 2021.

Article accepted: October 28, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter