Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 -

Subperiosteal endoscopic frontoplasty with temporal suture threads fixation

Frontoplastia endoscópica subperiostal com fixação temporal por fios de sutura

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The aging of the upper third of the face is characterized by ptosis of the eyebrow, glabellar wrinkles and frontal transverse wrinkles. Treatment can be performed through coronal frontoplasty, temporal frontoplasty with limited incisions and endoscopic frontoplasty. The aim of this study is to describe the technique of subperiosteal endoscopic frontoplasty with myotomy of the muscles of the glabellar region and fixation of the flap in the deep temporal fascia, evaluating its applicability and effectiveness.

Methods: Twenty-four female patients who underwent endoscopic frontoplasty associated with upper blepharoplasty, aged between 37 and 72 years old, over a 10-year period were evaluated. Measurements between the distance from the inter-pupillary line and the upper portion of the eyebrow were performed through photographic analysis using the Mirror 6.0 digital image system, in the medial, central and lateral regions on each side, in the preoperative period, and in the 6 month postoperative period.

Results: The average age was 52 years. There was statistical significance (p<0.05) in all evaluated eyebrow areas, the mean was 0.3 cm higher. Complications were: 1 case of wire extrusion, 1 case of asymmetry, 2 cases of insufficient correction of the eyebrow and 2 cases of recurrence of glabellar wrinkles.

Conclusion: Subperiosteal endoscopic frontoplasty with myotomy of the muscles of the glabellar region and fixation of the flap in the deep temporal fascia with stitches, proved to be effective in the treatment of aging of the upper third of the face, with statistically proven results, low morbidity and good aesthetic results.

Keywords: Aesthetics; Face; Frontal Bone; Periosteum; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Video recording.

RESUMO

Introdução: O envelhecimento do terço superior da face se caracteriza por ptose da sobrancelha, rugas glabelares e rugas transversais frontais. O tratamento pode ser realizado através da frontoplastia coronal, da frontoplastia temporal com incisões limitadas e da frontoplastia endoscópica. O objetivo deste estudo é descrever a técnica de frontoplastia endoscópica subperiostal com miotomia dos músculos da região glabelar e fixação do retalho na fáscia temporal profunda, avaliando sua aplicabilidade e eficácia.

Métodos: Foram avaliadas 24 pacientes, do sexo feminino, submetidas a frontoplastia endoscópica associada a blefaroplastia superior, com idade variando entre 37 e 72 anos, em um período de 10 anos. Medidas entre a distância da linha interpupilar e a porção superior da sobrancelha foram realizadas através de análise fotográfica com uso do sistema digital de imagem Mirror 6,0, na região medial, central e lateral de cada lado, no pré-operatório, e no pós-operatório de 6 meses.

Resultados: A média de idade foi de 52 anos. Houve significância estatística (p<0,05) em todas as áreas da sobrancelha avaliadas, a média de foi de 0,3 cm mais alta. As complicações foram: 1 caso de extrusão fio, 1 caso de assimetria, 2 casos de correção insuficiente da sobrancelha e 2 casos de recidiva de rugas glabelares.

Conclusão: A frontoplastia endoscópica subperiostal com miotomia dos músculos da região glabelar e flxação do retalho na fáscia temporal profunda com pontos demonstrou ser efetiva no tratamento do envelhecimento do terço superior da face, com resultados estatisticamente comprovados, baixa morbidade e bons resultados estéticos.

Palavras-chave: Estética; Face; Osso frontal; Periósteo; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Gravação em vídeo

INTRODUCTION

The upper third of the face’s aging is characterized by eyebrow ptosis (eyebrows), glabellar and deep, transverse wrinkles in the frontal region1.

The surgical treatment of aging in this area can be performed using the classic technique of open coronal frontoplasty (FCA), temporal frontoplasty with limited incisions (associated with the treatment of glabellar wrinkles through the upper blepharoplasty incision - described by Knize), and frontoplasty endoscopy (EF)1,2.

EF was first described by Vasconez3,4, in the early 1990s, for eyebrow repositioning (“brown lift”). At the same time, Isse5 described EF with a subperiosteal approach and myotomy of the musculature of the glabellar region; and, subsequently, Ramirez6 presented his series similar to that of Isse5 (subperiosteal access and myotomy of the corrugator muscle and the procerus muscle), thus providing a strong technical and scientific basis for EF.

Regarding the ways of fixing the elevated and suspended flap, they can be done through bone tunnels, absorbable screws and sutures of the flap in the deep temporal fascia and the temporal muscle1,2,7. The flap suturing technique avoids possible bone erosion and infections with screws (foreign bodies)1.

OBJECTIVE

This study aims to describe the subperiosteal EF technique with myotomy of the muscles of the glabellar region (corrugator muscle, depressor superciliary muscle and procerus muscle) and fixation of the flap in the deep temporal fascia, evaluating its applicability and effectiveness.

METHODS

We retrospectively evaluated 24 female patients who underwent EF associated with upper blepharoplasty, aged between 37 and 72 years, over 10 years (from January 2010 to December 2020), at Lincoln Graça Neto - Plastic Surgery, in Curitiba, PR. Patients with previous frontoplasty surgery were excluded from the study.

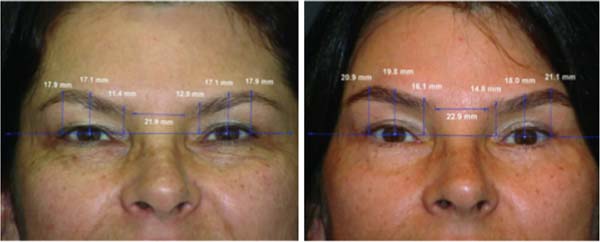

Measurements were performed through photographic analysis using the Mirror 6.0 digital imaging system (Canfield Imaging Systems, Fairfield, NJ), measuring the distance between the interpupillary line to the upper portion of the eyebrow in the medial, central and side on each side; preoperatively, and 6 months postoperatively (PO) (Figure 1).

This study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution and was carried out following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964).

Operative Technique

Patient in the supine position, administered 1 g of intravenous cefazolin, under local anesthesia (20 ml 2% lidocaine + 20 ml 1% ropivacaine + 160 ml of saline solution + 1:1000 adrenaline) and sedation. The entire frontal region was infiltrated, up to the eyebrows, glabellar region and temporal fossa, extending to the zygomatic arch and prominence of the malar bone.

Five incisions were made on the scalp, one of them in the midline (sagittal), two for sagittal (one on each side) with a length of 1 cm, and two temporal incisions of 3 cm (being these coronal and lateral to the temporal fusion line - LT) (Figure 2).

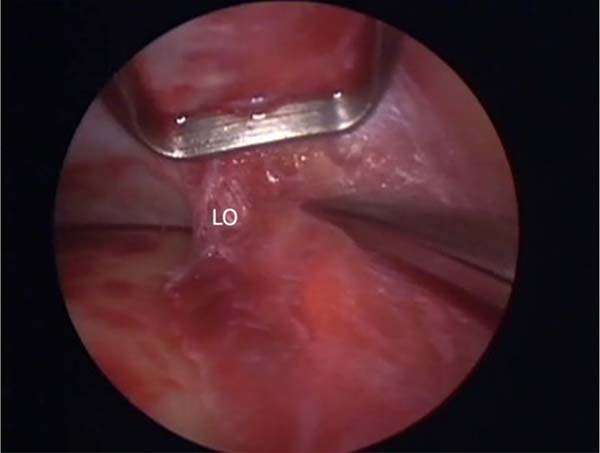

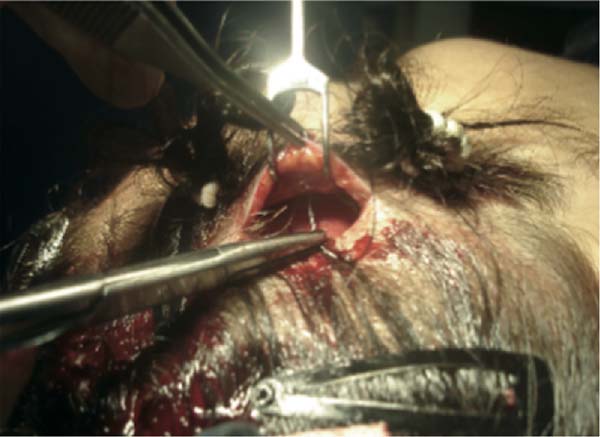

The dissection is subperiosteal with an inferior direction in the frontal region up to 2 cm above the orbital rim and laterally up to the TL; here, the periosteum is opened to gain access to the overlying anatomical structures. Laterally, in the temporal region, the dissection is performed below the posterior layer of the superficial temporal fascia and above the deep temporal fascia. The direction is also inferior until reaching the sentinel vein, the orbital ligament, the temporal zygomatic nerves (lateral and medial - sensory) and the lateral canthal ligament (here already in the supraperiosteal plane) (Figure 3).

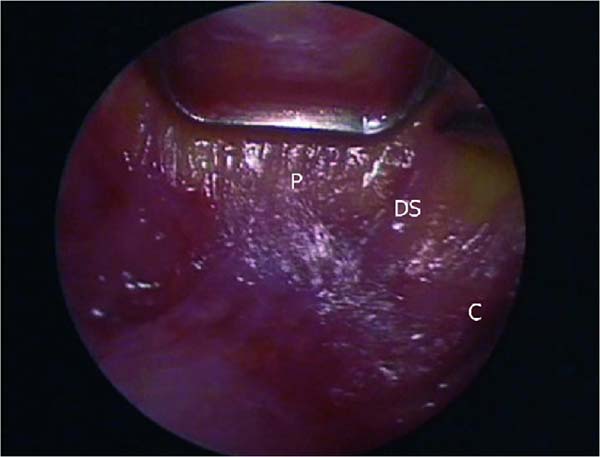

The orbital ligament must be sectioned and released with long Metzenbaum scissors, as well as the entire TL, from lateral to medial until communicating the two dissection planes, the lateral one (in the temporal region and below the superficial temporal fascia) and the central one in the region frontal (subperiosteal). Once the periosteum has been incised, the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves are dissected and preserved, the muscles of the glabellar region are approached, and a partial myectomy of the corrugator, superciliary depressor and procerus muscles is performed (Figure 4). Long curved Kelly forceps are used here.

The flap is fixed in the temporal region, fixing the flap in the deep temporal fascia, as described by Knize1, using nylon threads with 2 “X” stitches (Figure 5). The excess skin (redundant skin) of the flap pulled superiorly is excised; then, simple nylon 4.0 stitches are used for scalp synthesis, and a micropore dressing is applied to the entire area of skin that was dissected.

Upper blepharoplasty was always performed after EF to allow the removal of only the real excess skin, thus avoiding cases of difficult upper eyelid occlusion.

The statistical analysis described the variables considered the mean, median, minimum value, maximum value and standard deviation. To compare the two moments of evaluation of the results (preoperative and PO moments), the “Student” t-test for paired samples was considered. P values less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

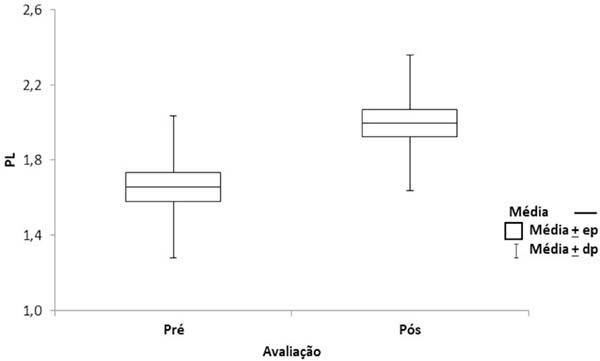

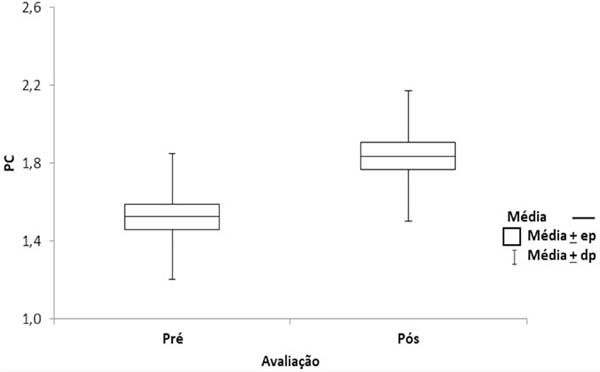

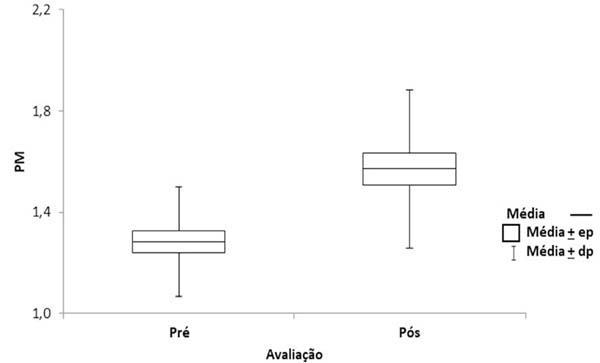

Twenty-four patients underwent surgery over 10 years. The age ranged from 37 to 72 years (Table 1). There was statistical significance in all evaluated eyebrow areas (Lateral part (LP), medial portion (MP) and Central part (CP)), and the mean was 0.3 cm, showing that the result was effective, as there was statistical significance (p<0.05) (Tables 2, 3 and 4 and Figures 6, 7 and 8).

| Variable | N | Average | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 24 | 52.4 | 48 | 37 | 72 | 9.2 |

| Time | N | Average | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation | p* value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 24 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1 | 2.8 | 0.4 | |

| post | 24 | 2.0 | two | 1.3 | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Post-Pre | 24 | 0.3 | 0.35 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

(*) Student’s t-test for paired samples; p<0.05

| Time | N | Average | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation | p* value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 24 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 2.5 | 0.3 | |

| Post | 24 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 0.3 | |

| Post-Pre | 24 | 0.3 | 0.25 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

(*) Student’s t-test for paired samples; p<0.05

| Time | N | Average | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation | p* value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 24 | 1.3 | 1.25 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.2 | |

| Post | 24 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 0.3 | |

| Post-Pre | 24 | 0.3 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

(*) Student’s t-test for paired samples; p<0.05

The null hypothesis of the same CP of the eyebrows was tested in the two evaluation moments versus the alternative hypothesis of different means.

The null hypothesis of an equal MP of the eyebrow in the two evaluation moments was tested versus the alternative hypothesis of different means.

Complications were:

1 case of nylon thread extrusion in the left temporal region

2 case of eyebrow asymmetry

3 cases of insufficient correction of the lateral portion of the eyebrow

4 cases of recurrence of glabellar wrinkles/insufficient muscle removal Figures 9 (A,B), 10 (A,B), 11 (A,B), 12 (A,B), 13 (A,B) and 14 (A, B).

DISCUSSION

There are several techniques for treating the frontal region. The most traditional is the ACF, which can be performed either in the subgaleal or subperiosteal plane, allowing the treatment of glabellar wrinkles and good positioning of the eyebrow. As for disadvantages, it determines long or definitive hypoesthesia of the portion posterior to the scar on the scalp, alopecia and extensive and more visible scars1,2.

Taking these aspects into account, Knize1,2,7 performed anatomical studies on the temporal fasciae and the positioning of the branches of the supraorbital nerve. From then on, he proposed the technique of temporal frontoplasty with limited incisions associated with the treatment of glabellar wrinkles through the upper blepharoplasty incision. This technique has in its favor the fact that it avoids sectioning the branches of the supraorbital nerve. As a disadvantage, it has the limitation for treating the eyebrow in the medial portion and always having to be associated with upper blepharoplasty to treat glabellar wrinkles.

EF, in turn, allows wide dissection of the flap, maximizing the image with easy identification of important anatomical structures, such as nerves and muscles, good eyebrow repositioning, avoiding scalp hypoesthesia and less chance of alopecia. As a disadvantage, it requires specific training and acquisition of videoendoscopy surgical material7-9.

The subperiosteal dissection plane used in this study, already proposed in the 1990s by Isse5 and Ramirez6, presents less bleeding and is below the plane through which the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerve branches pass. That is, it is safer and has less morbidity5-7. The subgaleal plane also has against it the fact that it has less adhesion and less chance of fixation10,11.

The most used forms of fixation are the bone tunnel, absorbable screws and fixation of the flap with wires in the temporal region1,12. Regardless of the form of fixation, the function would be to stabilize the flap until it heals and adhere and does not pull it superiorly in excess because fixation under tension causes recurrence. The bone tunnel technique is quite safe and effective, whereas absorbable screws are financially more expensive8,9,11. The use of wires with “X” stitches in the temporal region, as described by Knize, has low cost, low morbidity, does not require special equipment for bone drilling, and is very fast and reproducible.

Going in the opposite direction, Troilius11 demonstrated that there was no need for flap fixation due to periosteal adherence. In our country, Casagrande et al.13 described temporal fixation using a personalized needle as a successful treatment; and Graf et al.14 published, in 2005, their 8-year experience with videoendoscopy.

The eyebrow elevation measurement method used was the same proposed by Graf et al.8, being easy to perform and reproducible, analyzing and comparing preoperative and 6-month PO measurements. The average brow lift was 3 mm across its entire length - this value was observed in MP, CP and LP. This demonstrates uniformity in the treatment and the effectiveness of the surgical technique used. In the LP, the variation of measurements was from 1.3 to 3.0 mm, with a standard deviation of 0.4 and p<0.001. Regarding complications, there were a low number and no cases of serious complications such as injury to the temporal branch of the facial nerve.

The limitation of this study is that the results were not compared with other fixation techniques, such as the one using bone tunnels.

CONCLUSION

Subperiosteal EF with myotomy of the muscles of the glabellar region and fixation of the flap in the deep temporal fascia with stitches proved to be effective in treating aging of the upper third of the face, with statistically proven results, low morbidity and good aesthetic results.

REFERENCES

1. Knize DM. Limited-incision forehead lift for eyebrow elevation to enhance upper blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(7):1334-42.

2. Knize DM. Limited incision foreheadplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(1):271-84; discussion 285-90.

3. Price CI. Minimally invasive plastic surgery: an historical perspective. Course. In: The Endoscopy Aesthetic Symposium; 1993 Dez 11-12; Baltimore, USA.

4. Vasconez LO. The use of the endoscope in brow lifting [video]. In: Annual Meeting of the Los Angeles County Society of Plastic Surgeons; 1992 Sep 12; Los Angeles, CA, USA.

5. Isse NG. Endoscopic forehead lift. In: Annual Meeting of the Los Angeles County Society of Plastic Surgeons; 1992 Sep 12; Los Angeles, CA, USA.

6. Ramirez OM. The anchor subperiosteal forehead lift. Plast Reconstr Surg.1995;95(6):993-1003; discussion 1004-6.

7. Knize DM. Reassesment of the coronal incision and subgaleal dissection for foreheadplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(2): 478-89; discussion 490-2.

8. Graf RM, Tolazzi ARD, Mansur AEC, Teixeira V. Endoscopic periosteal brow lift: evaluation and follow-up of eyebrow height. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(2):609-16.

9. Graf R, Pace D, Araujo LR, Damasio RC, Rippel R, Graça Neto L, et al. Forehead and Midface Endoscopic Surgery. In: Eisenmann-Klein M, Neuhann-Lorenz C, eds. Innovations in Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery. 1st ed. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2008. p. 243-52.

10. Troilius C. A comparison between subgaleal and subperiosteal brow lifts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(4):1079-90; discussion 1091-2.

11. Troilius C. Subperiosteal brow lifts without fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6):1595-603; discussion 1604-5.

12. de la Fuente A, Santamaría AB. Endoscopic forehead lift: is it effective? Aesthetic Surg J. 2002;22(2):113-20.

13. Casagrande C, Saltz R, Chem R, Pinto R, Collares M. Direct needle fixation in endoscopic facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Surg J. 2000;20(5):361-7.

14. Graf R, Pace D, Araújo LR. Cirurgia videoendoscópica frontal e de terço médio: experiência de 8 anos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2005;20(4):197-203.

1. Lincoln Graça Neto - Plastic Surgery, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

2. Pontifícia Universidade Católica of Paraná, Medical School, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

| COLLABORATIONS | |

|---|---|

| LGN | Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

| LRRA | Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Software, Supervision |

| ACMG | Data Curation, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation |

Corresponding author: Lincoln Graça Neto, Rua Ângelo Sampaio, 2029, Batel, Curitiba, PR, Brazil. Zip Code 80420-160, E-mail: lgracaneto@hotmail.com

Article received: March 22, 2021.

Article accepted: July 14, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter