Case Report - Year 2021 - Volume 36 -

Breast discomfort after augmentation mammoplasty: a case report

Desconforto mamário após mamoplastia de aumento: relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Mammoplasty with prostheses is one of the most performed plastic surgeries in the world. However, the healing process around the implant and the presence of a biofilm can lead to the development of pathologies such as capsular contracture and seroma. These pathologies seem to be physiologically related to the development of lymphoma associated with breast implants (BIA-ALCL), which is also a differential diagnosis. The purpose of this study is to report the case of a patient with breast discomfort who, after two previous surgeries for seroma drainage and prosthesis replacement, presented breast discomfort and alteration in imaging of the left breast. She was, submitted to a capsulectomy in a block of the left breast and complete on the right, having her prostheses replaced. Bia-ALCL investigation tests were negative and pathological findings were suggestive of left capsular contracture and double capsule formation on the right. The study emphasizes the importance of differential diagnosis in mammary pathologies, long-term follow-up, and prophylaxis measures in biofilm formation.

Keywords: Seroma; Biofilms; Capsular contracture in implants; Large cell anaplastic lymphoma; Breast implants.

RESUMO

A mamoplastia com próteses é uma das cirurgias plásticas mais realizadas no mundo. O processo cicatricial ao redor do implante e a presença de um biofilme pode acarretar o desenvolvimento de patologias como contratura capsular e seroma. Essas patologias parecem estar relacionadas fisiopatologicamente com o desenvolvimento do linfoma associado aos implantes mamários (BIA-ALCL), sendo este também um diagnóstico diferencial. A proposta deste trabalho é relatar o caso de uma paciente com desconforto mamário, que após 2 cirurgias prévias para drenagem de seroma e troca de próteses, apresentava desconforto mamário e alteração em exames de imagens da mama esquerda. Sendo submetida a uma capsulectomia em bloco da mama esquerda e completa à direita, tendo suas próteses substituídas. Os exames para investigação de BIA-ALCL foram negativos e os achados patológicos foram sugestivos de contratura capsular à esquerda e formação de dupla cápsula à direita. O trabalho enfatiza a importância do diagnóstico diferencial em patologias mamárias, o acompanhamento a longo prazo e medidas de profilaxia na formação do biofilme.

Palavras-chave: Seroma; Biofilmes; Contratura capsular em implantes; Linfoma anaplásico de células grandes; Implantes de mama.

INTRODUCTION

The placement of breast prostheses promotes physiological scar reactions around the implant, forming a fibrous capsule that has been related to the development of several breast pathologies¹. Among them stand out seromas, capsular contracture and more recently, giant anaplastic lymphoma associated with a breast implant (BIA-ALCL)2,3.

BIA-ALCL, a rare malignancy described for the first time more than 20 years ago³, with pathophysiology known to be related to the periprosthetic capsule, recently generated greater concern after an open announcement from the FDA to the general population4.

The slow evolution and nonspecific clinical findings of the disease, in addition to the simultaneous increase in the worldwide incidence of BIA-ALCL and the procedure for the placement of breast prostheses itself, makes it essential to discuss and raise awareness in medical practice for early, careful, and individualized recognition of the differential diagnoses of breast pathologies after augmentation mammoplasty with prosthesis.

This study aims to review the diagnosis differentiating from breast discomfort after augmentation mammoplasty, calling attention to preventing biofilm formation and the importance of suspecting BIA-ALCL.

CASE REPORT

The case report follows the model recommended by SCARE5, being approved by the ethics and research committee of the Franciscan University under opinion number 4,023,210.

A 36-year-old female, white patient, nutritionist, sought care in a private clinic, referring discomfort in the left breast for approximately one year.

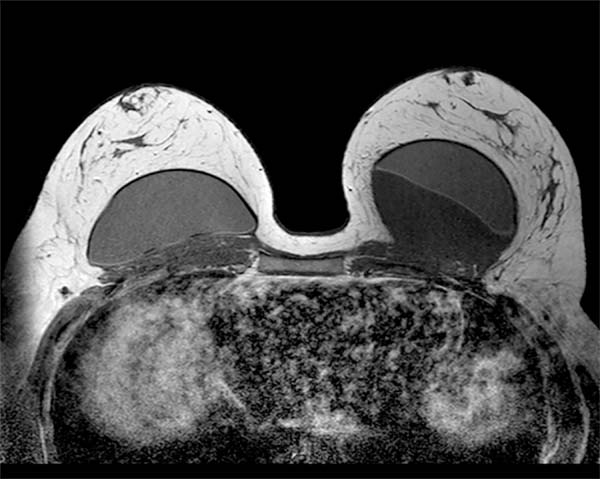

Previously healthy patient, BMI of 30kg/m2 with no history of smoking, no personal and family history of neoplasms. Previous history of mastopexy with a textured implant in 2015, having suture dehiscence in the left breast, being submitted to resuture two months later, with a satisfactory resolution. However, in 2016, she presented seroma (125ml) in her left breast. Cultural tests were negative, submitted to implant replacement, and macro textured, round high-profile implants of 310g were used in this surgery. In 2018, the patient presented discomfort in the left breast, but with normal tests (resonance and ultrasound). In 2019, with the persistence of symptoms, she again underwent magnetic resonance imaging, which showed a small collection of fluid in the region after the left breast implant (6ml), bi-RADS II classification (Figure 1), when she sought care.

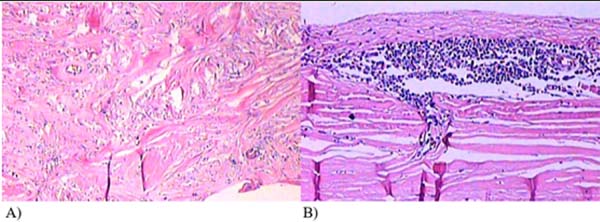

Considering the small volume and the location of difficult access for puncture or material collection, the surgical procedure was decided. In September 2019, through an incision in an enlarged breast groove, a complete block capsulectomy was performed in the left breast and a total capsulectomy on the right with implant replacement. In this procedure, the measures of capsular contracture reduction and biofilm formation were adopted. The pocket was washed with antibiotic solution, a change of gloves, and minimal implant management. This procedure was used round prostheses, microtextured, high profile and volume of 300cc. The left breast capsule was thickened, with the presence of septation in the posterior region with translucent fluid (Figure 2). The right breast presented a double capsule, with slippage between the leaflets but without fluid. All material was sent for histopathological analysis and research of CD30 and ALK, considering the possibility of BIA-ALCL (Figures 3 and 4). After the procedure, there were no complications, and the patient remained satisfied and asymptomatic in a follow-up one year after surgery.

DISCUSSION

The case highlights the importance of differentiating the physiological reaction of the organism to breast implantation from pathologies such as capsular contracture, seroma formation and BIA-ALCL. Although essentially, the scar reaction begins with the recruitment of inflammatory cells and later with fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, forming the periprosthetic capsule, some conditions may cause an imbalance in this process2,6.

After the prosthesis placement in this patient in 2015, there was dehiscence in the left breast surgical wound that may have favored the formation of a biofilm around the left implant 2,6, which could explain the formation of unilateral seroma, even years after placement6,7. Bengtson et al. (2011) 8 associate the formation of late seroma with a double capsule of circumferential fibrous adhesion, with an internal layer adhered to the prosthesis and the external to the breast tissue, but this did not happen in the right breast. Hall-Findlay (2011)9highlights the possible mechanical cause of late seroma, associated with separation of the capsule into two layers with rough surfaces (double capsule) after microtraumas, creating seroma due to shear forces6,9.

Due to seroma in 2016, prostheses and partial capsulectomy were changed, and only microbiological tests were performed, which came negative. However, the patient presented breast discomfort 2 years later, probably due to a capsular contracture, even if not evidenced in the tests in 2018.

Fibrotic tissue contraction around the implant, usually more frequent in the first 12 months after surgery, can cause changes in palpation, pain or visible deformity, which does not happen in normal situations¹. Capsular contracture is considered the inherent complication of the procedure with a greater need for reintervention², whose incidence and severity are correlated with the alignment of collagen fibers7.

In 2019, after repeating US and MRI, a small collection behind the left breast implant with about 6 ml was identified. In that same year, the breast prostheses of a given brand, associated with BIA-ALCL, were recalled, which was the case for the prostheses of this patient. In addition, reports in the literature have raised discussions about complications associated with textured breast implants, such as late seroma, double capsule and BIA-ALCL3,4,6.

Several studies consider that bacterial contamination, which can still occur during the prosthesis placement procedure, would be responsible for biofilm formation and, later, inflammatory response and activation of the immune system2. This response, associated with genetic predisposition, could over time be responsible for the development of BIA-ALCL due to chronic stimulation of bacterial antigen3,9-13.

According to the BIA-ALCL diagnostic and treatment guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in 201914, symptomatic periprosthetic effusions, more than one year after implantation, should be investigated by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging and tested for BIA-ALCL. If the finding is more than 50ml, an investigation is indicated through fine needle puncture and cytology, flow cytometry for characterization of “T” lymphocytes is requested, with immunohistochemistry research for CD30, ALK among other markers, if there is palpable mass, incisional biopsy or core biopsy can be performed and, in inconclusive cases, continue the investigation with more images.

According to Leberfinger et al. (2017) 15, the number of women with implants needed to cause 1 case of BIA-ALCL before 75 y.o. was 6,920. However, despite the low absolute risk for developing the disease, there has been an increase in incidence in recent years. BIA-ALCL is generally indolent and slow-growing, with an excellent prognosis, especially when treated with surgery, which should be to remove the implant with the fibrous capsule and any associated mass. Complete surgical excision prolongs overall survival and event-free survival compared to all other therapeutic interventions14.

Considering the nonspecific clinical presentation and the non-conclusive tests added to the patient’s fear of a pathology related to the brand of the prosthesis she had, an explant with complete block capsulectomy in the left breast and capsulectomy on the right, with bilateral replacement of the prostheses, was indicated. The capsules were completely removed in this procedure, and measures were performed to prevent biofilm formation and capsular contracture. The patient became asymptomatic, and the final diagnosis was capsular contracture, with posterior septation due to the residual capsule.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the importance of long-term follow-up of patients with breast prostheses, considering the increased incidence of reports of late seromas, double capsule, subclinical infections with biofilm formation and its pathophysiological mechanisms interconnected with the formation of BIA-ALCL, a pathology of excellent prognosis if treated at an early stage.

REFERENCES

1. Chao AH, Garza R, Povoski SP. A review of the use of silicone implants in breast surgery. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2016;13(2):143-56.

2. Mempin M, Hu H, Chowdhury D, Deva A, Vickery K. The A, B and C’s of silicone breast implants: anaplastic large cell lymphoma, biofilm and capsular contracture. Materials (Basel). 2018 Nov;11(12):2393.

3. Real DSS, Resendes BS. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: a systematic literature review. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34(4):531-8.

4. De Boer M, Van Leeuwen FE, Hauptmann M, Overbeek LIH, De Boer JP, Hijmering NJ, et al. Breast implants and the risk of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in the breast. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Mar;4(3):335-41.

5. Agha RA, Franchi T, Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Kerwan A, SCARE Group. The SCARE 202 guideline: updating consensus surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg. 2020 Dez;84:226-30.

6. Scala FD, Polizzi RJ, Casala TG, Santos FZF, Squarisi JMO, Freitas DIBV. Late seroma in breast reconstructions and mammoplasty with silicone implants: a case report and literature review. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(3):468-72.

7. Calobrace MB, Schwartz MR, Zeidler KR, Pittman TA, Cohen R, Stevens WG. Long-term safety of textured and smooth breast implants. Aesthet Surg J. 2017 Dez;38(1):38-48.

8. Bengtson B, Brody GS, Brown MH, Glicksman C, Hammond D, Kaplan H, et al. Managing late periprosthetic fluid collections (seroma) in patients with breast implants: a consensus panel recommendation and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Jul;128(1):1-7.

9. Hall-Findlay EJ. Breast implant complication review: double capsules and late seromas. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Jan;127(1):56-66.

10. Zingaretti N, Galvano F, Vittorini P, De Francesco F, Almesberger D, Riccio M, et al. Smooth prosthesis: our experience and current state of art in the use of smooth sub-muscular silicone gel breast implants. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43:1454-66. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-019-01464-9

11. Fricke A, Wagner JA, Kricheldorff J, Rancsó C, Von Fritschen U. Microbial detection in seroma fluid preceding the diagnosis of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Case Reports Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2019;6(1):116-20.

12. Moon DJ, Deva AK. Adverse events associated with breast implants: the role of bacterial infection and biofilm. Clin Plast Surg. 2021 Jan;48(1):101-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2020.09.009

13. Batista BN, Garicochea B, Aguilar VLN, Millan FMCS, Fraga MFP, Sampaio MMC, et al. Report of a case of anaplastic large cell lymphoma associated with a breast implant in a Brazilian patient. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2017;32(3):445-9.

14. Clemens MW, Jacobsen ED, Horwitz SM. 2019 NCCN consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Jan;3939(Supl 1):S3-13.

15. Leberfinger AN, Behar BJ, Williams NC, Rakszawski KL, Potochny JD, MacKay DR, et al. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017 Dez;152(12):1161-8.

1. Franciscana University, Faculty of Medicine, Santa Maria, RS, Brazil.

GCR Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

VHA Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author: Giancarlo Cervo Rechia Rua Pinheiro Machado, 2494, Sala 402, Bairro Centro, Santa Maria, RS, Brazil. Zip Code 97050-600 E-mail: giancarlorechia@hotmail.com

Article received: May 22, 2020.

Article accepted: April 23, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter