Case Report - Year 2021 - Volume 36 -

Marjolin ulcer in pressure injury scar: a case report

Úlcera de Marjolin em cicatriz de lesão por pressão: relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Marjolin ulcer (epidermoid carcinoma) is a rare condition that arises from a chronic skin lesion. We present a patient who developed an epidermoid carcinoma in the scar tissue of a pressure ulcer. After eleven years of surgery to correct a pressure ulcer in the right gluteus, the patient developed an epidermoid carcinoma in a pressure ulcer in the left gluteus and neglected the condition. Wide resection of the lesion was performed with free margins in the final histopathological result. Marjolin ulcer is an expression that commonly refers to the malignant degeneration of chronic wounds that have not healed or healed by secondary intention. It is often described as various types of lesions, including the scars of pressure ulcers. The pathogenic mechanisms behind the malignant transformation of these lesions have not yet been completely elucidated. The diagnosis is initially made by clinical examination due to the lesion aspect and is confirmed by biopsy. Surgery is the choice treatment closing the defect with flaps or grafts, depending on each case.

Keywords: Squamous cell carcinoma; Pressure ulcer; Wounds and injuries; Scar; Ulcer.

RESUMO

A úlcera de Marjolin (carcinoma epidermoide) é uma condição rara que surge de uma lesão cutânea crônica. Apresentamos o caso de uma paciente que desenvolveu um carcinoma epidermoide em tecido cicatricial de uma úlcera por pressão. Depois de onze anos da cirurgia para corrigir uma úlcera por pressão no glúteo direito, a paciente desenvolveu um carcinoma epidermoide numa úlcera por pressão no glúteo esquerdo e negligenciou a afecção. Realizou-se ampla ressecção da lesão com margens livres no resultado histopatológico final. Úlcera de Marjolin é uma expressão que comumente se refere à degeneração maligna de feridas crônicas que não curaram ou curaram por segunda intenção. Com frequência se descreve como vários tipos de lesiones, incluídas as cicatrizes das úlceras por pressão. Os mecanismos patogênicos por trás da transformação maligna destas lesões ainda não foram dilucidados por completo. O diagnóstico se realiza inicialmente mediante exame clínico devido ao aspecto da lesão e se confirma por biópsia. A cirurgia é o tratamento de eleição com o fechamento do defeito com retalhos ou enxertos, dependendo de cada caso.

Palavras-chave: Carcinoma de células escamosas; Úlcera de pressão; Feridas e injúrias; Cicatriz; Úlcera.

INTRODUCTION

Marjolin ulcer (epidermoid carcinoma) is a rare and well-described complication of a precursor chronic skin lesion. Usually occurs in burn scars, ulcers due to venous insufficiency, chronic fistulas in osteomyelitis and less often in scars of pressure ulcers1.

Pressure ulcer is a common problem that affects the older people and with physical disabilities. Continuous pressure, shear, or light friction may cause microvascular occlusion, ischemia, and necrosis2. Epidermoid carcinoma is diagnosed by biopsy of the lesion. The clinical course is usually fast, and the mortality rate is high3.

Surgery is the treatment of choice. Radiotherapy has been used as a palliative treatment4. We present a case of epidermoid carcinoma after ten years of graft surgery by pressure ulcers in the gluteus and the appearance of a new ulcer neglected by the patient, which led to extensive epidermoid carcinoma development. Besides, we discuss the aspects that led to the suspicion of this condition and the therapeutic options.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old woman was born with myelomeningocele. Three months after birth, the patient underwent corrective surgery. However, she developed paraplegia. He progressed with pressure ulcers in both glutes that were treated conservatively. After the appearance of a pressure ulcer in the right gluteal region 11 years ago, an operative debridement was performed with a subsequent skin graft to correct the defect. It measured around 10cm in its largest diameter. Nine years and six months later, an ulcerated lesion emerged in his left gluteal region, showing rapid and progressive growth. However, the patient did not seek medical attention.

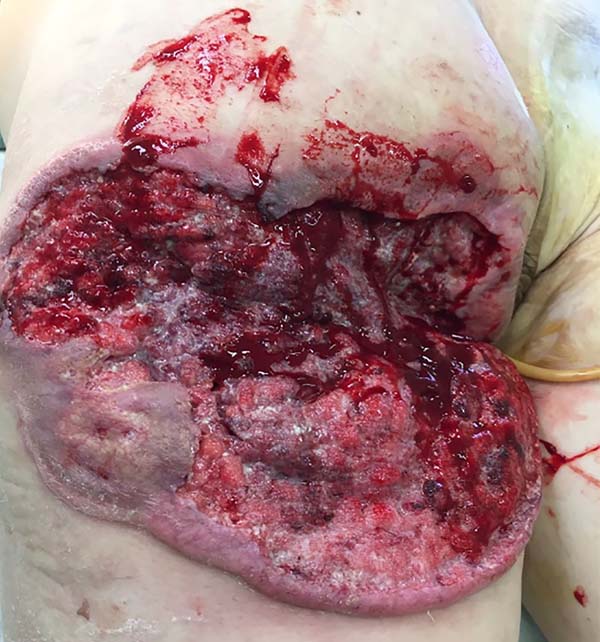

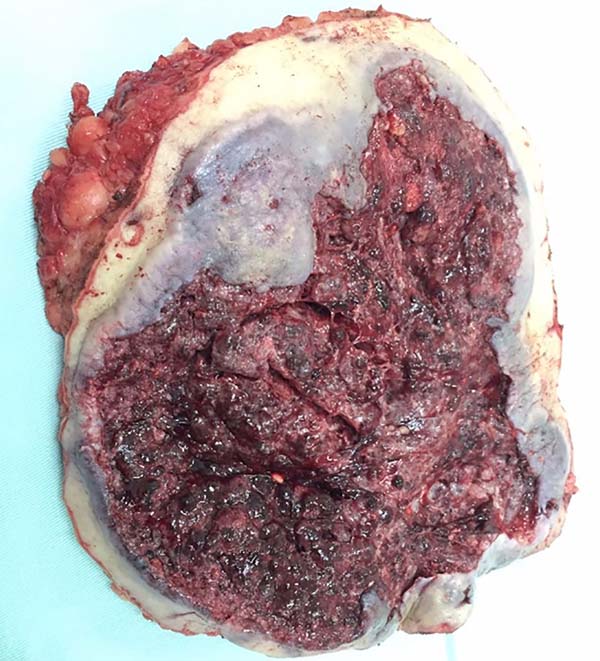

On physical examination, the patient presented an extensive ulcer (30x30cm2) in the left gluteus and the right hip in the posterior region that extended to the perianal zone. The ulcer had a foul odor, purulent secretion, necrotic base and raised edges. The patient had anemia, poor general health status, and received two units of red blood cell concentrate and cefepime. No suspected lymph nodes were found in the inguinal region, and chest X-ray was normal. Biopsy of the lesion confirmed a moderately differentiated epidermoid carcinoma. After handling the infection and anemia, the patient underwent an enlarged resection of the lesion. Final histopathological analysis confirmed a G2 epidermoid carcinoma with free lateral and deep margins. Postoperatively, the patient acquired an E. coli infection sensitive to cefepime. After granulation of the surgical wound and infection control, a total skin graft was discharged from the hospital.

Two months after surgical treatment, the patient underwent a free skin graft on the left gluteus with complete graft integration. Two months after treatment, the patient achieved a good recovery and showed no evidence of recurrent carcinoma (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5). The patient signed an informed consent form for the publication of the current report. The ethics committee approved the case with number 2,402,686.

DISCUSSION

Marjolin’s ulcer is the eponym of malignant degeneration of chronic wounds that did not proceed with the normal healing process or healing by secondary intention. Marjolin ulcers have been commonly described in various types of lesions such as pressure ulcers, venous insufficiency ulcers, irradiated tissues, diabetic ulcers, osteomyelitis, and other less common lesions such as hidradenitis, pilonidal cysts, urination fistulas, vaccination scars, herpes zoster scars, and even graft scars. However, it is described more frequently as a malignant transformation of burn scars5. This study is a rare report of Majorlin’s ulcer that arises in scars of pressure ulcers.

The pathogenic mechanisms behind the development of malignant transformation in burn scars or wounds exposed to repetitive trauma, significantly those that heal by second intention, have not yet been fully clarified. However, some authors have suggested that these lesions’ immunological environment is unfavorable for immunosuppression due to the low vascularization of scar tissue6. It has been suggested that the elevated expression of proto-oncogenes is a mechanism of malignant degeneration7. Other researchers have suggested that avascular scar tissue in chronic wounds may interfere with the motility of lymphocytes8.

Marjolin’s ulcer is commonly confused with infected ulceration that is produced in scar tissue. Changes such as the appearance of non-healing ulcers and increased bone circumference with raised edges, foul odor, pain, and blood drainage indicate a malignant transformation. At more advanced stages, invasion and underlying bone destruction may occur. A surgical biopsy performed in multiple locations is recommended to confirm the diagnosis9.

In this report, the patient developed a malignant neoplasm after the appearance of a new pressure ulcer that grew rapidly nine years and six months after the treatment of a previous pressure ulcer in the ipsilateral gluteus, showing the aggressive nature of the tumor. Biopsy of rapidly increasing pressure ulcers that suggest a malignant transformation is essential to improve the prognosis of the patient3. In the literature, we found seven published cases of epidermoid carcinoma that occur in pressure ulcers. The patients’ age ranged from 30 to 85 years, and the disease’s progression was 14 years on average (Table 1).

| Authors | Age at diagnosis | Region | Duration of clinical course | Treatment of epidermoid carcinoma | Size of Carcinoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knudsen e Biering-Srensen 200811 | 57 years | Left sacral region | 10 years | Surgery and radiation therapy (patient died) | Not mentioned |

| Fairbairn e Hamilton 20112 | 41 years | Sacral region, buttocks and perineum | 10 years | Surgical excision | Not mentioned |

| Cocchetto et al. 20131 | 30 years | Sacral region | 3 years | Patient died before any treatment of the lesion was begun | 15 x 12 cm |

| Eltorai et al. 20024 | 56 years | Sacrococygeal region | 25 years | Surgical excision, radiation therapy and chemotherapy (patient died) | 4 cm diameter and 5 cm deep in the subcutaneous tissue |

| Khan et al. 201612 | 85 years | 10 years | Surgical excision | 3.5×4 cm with overlapping growth of 1.5 x 2 cm at the upper region | |

| Berkwits L et al. 198613 | 42 years | Sacred region | 14 years | Surgical excision | Not mentioned |

| Dumurgier et al. 199114 | Mean of 55 years | Three patients in sacral region, one in trochanter and one in the calcaneum | Mean interval of 30 years | Surgical excision, radiation therapy and chemotherapy (patients died) | Mentioned in only one case: 2x3cm in the sacral region |

According to Pekarek et al., in 201110, well-differentiated lesions are less aggressive; therefore, patients with these lesions have a better prognosis. The overall 3-year survival rate is 65% to 75%, while the 10-year survival rate is 34%. However, metastases in the inguinal lymph nodes result in a three-year survival rate of 35% to 50%. In the present case, inguinal lymph nodes were normal in clinical and sonographic examinations. On patient follow-up, attention should be focused on examining inguinal lymph nodes, as ganglion metastases may occur after treating the primary lesion. There should be rapid identification of ganglion metastases and the institution of surgical treatment with inguinal lymphadenectomy.

Surgery is the treatment of choice for Marjolin ulcer, and wide excision with margins (2 to 3 cm) is recommended. This approach was adopted in the present case. Radiotherapy has been the palliative treatment used. The response to systemic chemotherapy is usually deficient4.

REFERENCES

1. Cocchetto V, Magrin P, Paula RA, Aidé M, Razo LM, Pantaleão L. Squamous cell carcinoma in chronic wound: Marjolin ulcer. Dermatol Online J [Internet]. 2013; 19(2). Available from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7zf8466k

2. Fairbairn NG, Hamilton SA. Management of Marjolin's ulcer in a chronic pressure sore secondary to paraplegia: a radical surgical solution. Int Wound J. 2011 Aug;8(5):533-6.

3. Mustoe T, Upton J, Marcellino V, Tun CJ, Rossier AB, Hachend HJ. Carcinoma in chronic pressure sores: a fulminant disease process. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:116-21.

4. Eltorai IM, Montroy RE, Kobayashi M, Jakowatz J, Guttierez P. Marjolin's ulcer in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25(3):191-6.

5. Vieira RRBT, Batista ALE, Batista ABE, Rosa JVS, Diniz ACO, Leite GF, et al. Marjolin's ulcer: revisão de literatura e relato de caso. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2016;15(3):179-84.

6. Bostwick J, Pendergrast Junior WJ, Vasconez LO. Marjolin's ulcer: an immunologically privileged tumor?. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57(1):66-9.

7. Smith J, Mello LF, Nogueira Neto NC, Meohas W, Pinto LW, Campos VA, et al. Malignancy in chronic ulcers and scars of the leg (Marjolin's ulcer): a study of 21 patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2001 Jun;30(6):331-7.

8. Novick M, Gard DA, Hardy SB, Spira M. Burn scar carcinoma: a review and analysis of 46 cases. J Trauma. 1977;17(10):809-17.

9. Ochenduszkiewicz U, Matkowski R, Szynglarewicz B, Kornafel J. Marjolin's ulcer: malignant neoplasm arising in scars. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2006;11(3):135-8.

10. Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin's ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Col Certif Wound Spec. 2011 Set;3(3):60-4.

11. Knudsen MA, Biering-Srensen F. Development of Marjolin's ulcer following successful surgical treatment of chronic sacral pressure sore. Spinal Cord. 2008;46(3):239-40.

12. Khan K, Giannone AL, Mehrabi E, Khan A, Giannone RE. Marjolin's Ulcer Complicating a Pressure Sore: The Clock is Ticking. The American Journal of Case Reports. 2016;17:111-114.

13. Berkwits L, Yarkony GM, Lewis V. Marjolin's ulcer complicating a pressure ulcer: case report and literature review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67(11):831-833

14. Dumurgier C, Pujol G, Chevalley J, Bassoulet H, Ucla E, Stchepinsky P. Pressure sore carcinoma: a late but fulminant complication of pressure sores in spinal cord injury patients: case reports. Paraplegia.1991;29:390-395.

1. Centro Universitário UNINOVAFAPI, Oncology, Teresina, PI, Brazil.

2. Universidade Estadual do Piauí, Oncology, Teresina, PI, Brazil.

3. Oncocenter, Oncology, Teresina, PI, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Danilo Rafael da Silva Fontinele Rua Olavo Bilac, 2335, Centro, Teresina, PI, Brazil. Zip Code: 64001-280 E-mail: drsilvafontinele@gmail.com

Article received: January 11, 2020.

Article accepted: February 22, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none

COLLABORATIONS

AFM Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration

DRSF Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing - Original Draft Preparation

SCV Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing - Original Draft Preparation

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter