Case Report - Year 2021 - Volume 36 -

Pyoderma gangrenosum as a differential diagnosis of ischemic and infectious complications after abdominoplasty: a case report

O pioderma gangrenoso como diagnóstico diferencial de complicações isquêmicas e infecciosas após abdominoplastia: um relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Abdominoplasty is a procedure with a considerable rate of complications, even though, for the most part, it has a good prognosis. Some complications, however, can be catastrophic, such as extensive skin necrosis and serious infectious complications. Among the unusual causes of extensive skin loss in the postoperative period, we can mention gangrenous pyoderma (PG), a chronic, recurrent disease with unpredictable behavior and an unknown etiology. In the field of plastic surgery, this disease can clinically mimic ischemic or infectious postoperative complications, whose treatments differ completely from the treatment of PG.

Case Report: A 41-year-old female patient, previously healthy, underwent abdominoplasty associated with liposuction and breast augmentation with the placement of breast implants. The patient evolved with edema, hyperemia and pain in an abdominoplasty incision, in addition to systemic clinical involvement. She was submitted to surgical debridement and systemic treatment, with progressive worsening of the lesions. In view of the failure of the proposed treatments, the diagnostic hypothesis of gangrenous pyoderma was raised.

Conclusion: PG, although rare, should be considered as a differential diagnosis in cases of postoperative complications with skin loss and necrosis that do not respond to initial treatment measures, in addition to apparently infectious conditions that do not respond to adopted antibiotic therapies.

Keywords: Abdominoplasty; Pyoderma gangrenosum; Postoperative complications; Vesiculobullic dermatopathies; Differential diagnosis.

RESUMO

Introdução: A abdominoplastia é um procedimento com índice considerável de complicações, ainda que, em sua maioria, de bom prognóstico. Algumas complicações, entretanto, podem ser catastróficas, como a necrose extensa de pele e as complicações infecciosas graves. Dentre as causas incomuns de perda extensa de pele no pós-operatório, podemos citar o pioderma gangrenoso (PG), doença de curso crônico, recidivante, com comportamento imprevisível e de etiologia ainda desconhecida. No âmbito da cirurgia plástica, essa doença pode mimetizar clinicamente complicações pós-operatórias isquêmicas ou infecciosas, cujos tratamentos diferem por completo do tratamento do PG.

Relato de Caso: Paciente feminina, 41 anos, previamente hígida, foi submetida à abdominoplastia associada à lipoaspiração e mamoplastia de aumento com colocação de próteses mamárias. Evoluiu com edema, calor hiperemia e dor em incisão de abdominoplastia, além de comprometimento clínico sistêmico. Submetida a desbridamentos cirúrgicos e tratamento sistêmico, com piora progressiva das lesões. Diante do insucesso dos tratamentos propostos, aventada a hipótese diagnóstica de pioderma gangrenoso.

Conclusão: O PG, apesar de raro, deve ser aventado como diagnóstico diferencial em casos de complicações pós-operatórias com perda e necrose de pele que não respondem às medidas iniciais de tratamento, além de quadros aparentemente infecciosos que não respondem às terapias antibióticas adotadas.

Palavras-chave: Abdominoplastia; Pioderma gangrenoso; Complicações pós-operatórias; Dermatopatias vesiculobolhosas; Diagnóstico diferencial

INTRODUCTION

Abdominoplasty is one of the most performed cosmetic surgeries in the world, and its incidence increases progressively. According to the latest update of the national database of the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank) for the year 2018, the abdominoplasty was the 4th most performed cosmetic surgical procedure in the United States, corresponding to 10.2% of aesthetic surgeries performed this year1. These data are reflected worldwide, according to annual surveys conducted by ISAPS (International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery)2. In Brazil, according to the 2018 census of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery, abdominoplasty corresponds to the 3rd most performed cosmetic plastic surgery3.

The procedure can be performed in isolation or associated with liposuction and other cosmetic surgeries. Despite the various techniques already described, studied and used, abdominoplasty is a procedure with a relatively high complication rate, although most of them have a good prognosis4. Some complications, however, can be catastrophic. Extensive skin necrosis and severe infectious complications, such as necrotizing fasciitis, although rare, can threaten patients’ lives and cause aesthetic and functional sequelae.

Among the unusual causes of extensive skin loss in the postoperative period, we can mention pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), an inflammatory pathology of the skin with no infectious etiology but whose clinical manifestation may resemble infectious complications or necrosis due to ischemia. Pyoderma gangrenosum was first described by Cullenin19245 and Brusting et al. in 19306. It is a disease of chronic course, recurrent, with unpredictable behavior and of unknown etiology7. It is rare. It is estimated that its incidence occurs between 3 to 10 cases per million people/year8. It is believed that 25-50% of PG cases are idiopathic, but an immunological origin is suggestive since the association with systemic diseases of autoimmune cause is frequent9. The pathology mainly affects young women between 20 and 50 years. It is often associated with systemic comorbidities such as inflammatory bowel disease (chronic ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease), rheumatologic diseases (seronegative arthritis, rheumatoid, spondylitis and osteoarthritis), hematic diseases (myelocytic leukemias, hairy cell leukemia, myelofibrosis and monoclonal gamma disease) and neoplasms10.

PG is a rare neutrophilic dermatosis whose clinical manifestation varies. It is characterized by ulcerated and painful skin lesions, multiple or solitary, rapidly progressive, and a speckled and erythematous aspect11. Lesions can be quite destructive. It most often affects the lower limbs but can occur anywhere on the body. A phenomenon known and present in this pathology is pathergy, which consists of skin hyperactivity after trauma, including surgery, new lesions or extension and worsening of preexisting ones at the trauma site or surgical site. This phenomenon corroborates the hypothesis of immunological etiology, as it consists of an altered, exaggerated and uncontrolled immune response to a non-specific stimulus9.

The diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum is made by exclusion since the clinic is quite variable, the histopathology is non-specific, and there is no serological markers12. In the context of plastic surgery, this disease needs to be known to clinically mimic postoperative ischemic or infectious complications, whose treatments differ completely from pg treatment. Severe cases may occur with systemic toxicity, fever, shorty, and severe hypotension9.

This study aims to report a severe PG case with important systemic repercussions after abdominoplasty and discuss the importance of this pathology in the differential diagnosis of other postoperative complications.

CASE REPORT

This case report was carried out following the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association. The patient was instructed about the study and spontaneously signed the free and informed consent form.

A 41-year-old female patient, previously healthy, from Pará. She underwent abdominoplasty associated with liposuction and augmentation mammoplasty with breast prostheses’ placement in the city of Porto Alegre, in an institution outside the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA). She had a history of previous cesarean section, with no complications. She did not use routine medications and denied drug allergies.

On the 8th postoperative day, before admission to HCPA, the patient was diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis associated with cellulitis in the left upper limb (basilica vein), despite antithrombotic prophylaxis with enoxaparin for seven days after surgery. She started anticoagulant treatment at a full dose as directed by an attending clinical physician, in addition to oral antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin and clavulanate).

On the 11th postoperative day, she sought the emergence of HCPA under his assistant plastic surgeon’s guidance for edema, heat, hyperemia, and pain on flanks bilaterally with secretion drainage and persistent fever above 38°C. The patient arrived at the tachycardic emergency, pale, with borderline blood pressure (102/59mmHg), saturating 94-96% and febrile. On physical examination, cutaneous infiltration with edema, heat and important hyperemia was identified in lateral parts (flanks) of the abdominal incision, in addition to hyperemia and drainage of secretion in incisions of augmentation mammoplasty (Figure 1). Intravenous antibiotic (amoxicillin-clavulanate was initiated, subsequently staggered to cefepime and vancomycin under the guidance of the hospital infection control committee). Laboratory tests corroborated the infectious process hypothesis: C-reactive protein (CRP) 417.6mg/L, 32,310/µL leukocytes with 8% of sticks, 593,000 platelets and lactate 0.79mmol/L.

Surgical debridement was indicated for drainage and hygiene of surgical wound; procedure performed on the 12th day after abdominoplasty in the emergency room and under general anesthesia. Secretions from the abdominal wound and breasts were sent for analysis. Approximation sutures were performed to reduce the exposed area.

In the postoperative debridement period, the patient evolved with respiratory difficulty, requiring temporary ventilatory support with Hudson and Venturi mask to maintain saturation above 90%. Blood culture, collected upon arrival at the hospital, negatively affected bacterial growth (but the patient was already using amoxicillin + oral clavulanate before arrival). The analysis of the secretions collected also had a negative result for bacterial growth. There was no significant clinical improvement after surgery; tachycardic and febrile (axillary temperature up to 39.3°C) remained, in addition to presenting recurrent episodes of tachypnea and desaturation. Laboratory tests showed no improvement. Multidisciplinary follow-up (internal medicine, infectious diseases and plastic surgery) and clinical management oriented to sepsis’s hypothesis due to surgical wound infection were instituted. There was no clinical improvement even in the presence of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Computed tomography was performed to evaluate abdominal wall infiltration and exclude the necrotizing fasciitis hypothesis. No new subcutaneous collections or infiltrate scans away from the surgical wound were identified on imaging. Clinically, however, it presented considerable worsening of abdominal lesions, with extremely rapid and important progression. Ulcerated lesions adjacent to the operative incisions, with irregular and violaceous edges, with a necrotic center, whitish, softened and extremely friable, with drainage of purulent secretion, in addition to heat, local pain and drainage of purulent secretion (Figure 2).

Because of the non-clinical improvement, with the maintenance of tachycardia, tachypnea and fever, in addition to worsening the abdominal lesions, on the 2nd postoperative day of the first intervention (and 15° of the abdominoplasty), the patient underwent a new procedure for thorough washing and extensive wound debridement. A moderate amount of devitalized tissue was identified, which was removed in its entirety. The alterations were limited to the dermis and superficial subcutaneous tissue without reaching deep subcutaneous tissue or fascia. There was purulent exudate present but no deep collections. An open wound was left to control necrosis and infection. Due to the presence of hyperemia and secretion in the left breast surgical wound, we opted for the removal of breast prostheses bilaterally. It evolved with hemodynamic instability during surgery, requiring ICU admission. Antibiotic therapy was staggered to meropenem and linezolid under the guidance of the infectology team.

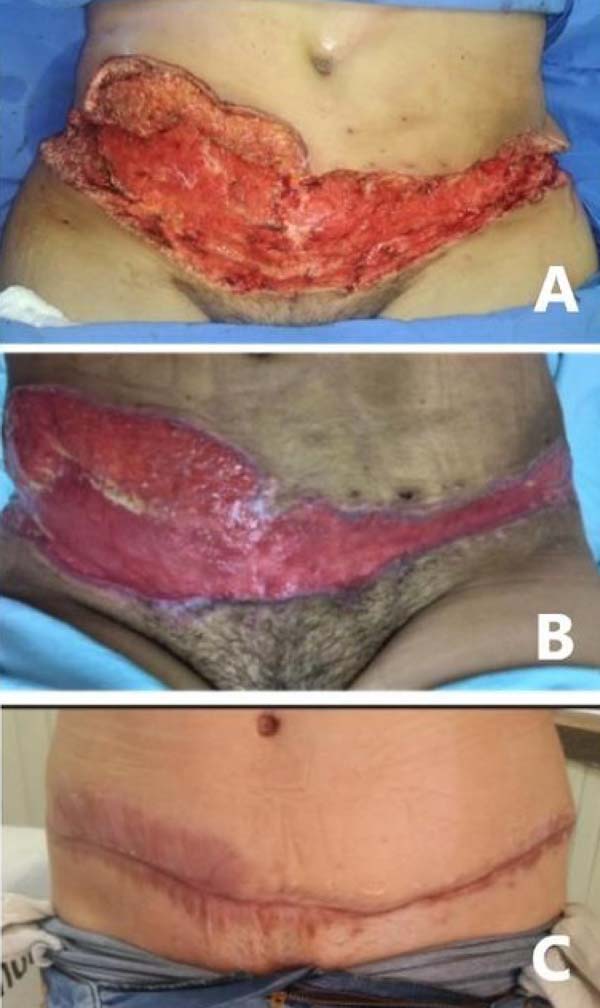

The patient showed little clinical improvement in the days following the new surgical intervention; she remained febrile, with increased leukogram and CRP, tachycardic and in need of vasoactive drugs, even at lower doses. There was progressive worsening of the necrotic areas, presenting the same aspect described previously (Figure 3). The worsening progression was rapid; in less than 12 hours, ulcers of violaceous edges were already identified, with a necrotic center, especially on the flanks (Figure 4). On the other hand, the incisions for removing breast prostheses evolved well, with good healing, without warning signs.

Two days after the last surgical intervention (17th postoperative of the abdominoplasty), a new debridement of the necrotic areas was performed in the operating room under general anesthesia. Material for cultural examination, including culture for mycobacteria, was collected again. Fragment of debrided tissue was sent for anatomopathological examination. Cultural examinations (including for mycobacteria)had a negative result. Histopathological examination was non-specific: acute suppurative inflammation in the dermis and hypodermis (cellulitis), in addition to lipophagic granuloma.

The patient maintained progressive worsening of the abdominal wound and slow clinical improvement. It evolved to hemodynamic stability without vasoactive drug use and did not present more episodes of ventilatory insufficiency. However, it remained febrile and altered laboratory tests (32940/µL leukocytes, with 6% of sticks, PCR 403mg/L). The antibiotic regimen was added to meropenem and linezolid, polymyxin B. Investigation for immunological disorders and, in the face of the failure of surgical debridement, the hypothesis of pyoderma gangrenosum was suggested. New skin biopsies were performed and analyzed by a pathologist experienced in dermatological diseases; the result found was: “acute suppurative inflammation with extensive tissue necrosis. The hypothesis of interstitial neutrophilic dermatosis should be evaluated.” Among the factors that went against the diagnosis of PG were: good healing of the mammary incisions, the absence of a previous history of similar lesions or related comorbidities, and the degree of systemic involvement.

On the 11th day of hospitalization at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, given the evident worsening of abdominal lesions and the failure of the therapies instituted so far, focusing on the diagnostic hypothesis of pyoderma gangrenosum, it was decided to perform a therapeutic test with intravenous corticosteroid (dexamethasone) at a dose of 10mg three times a day.

RESULTS

After the intravenous therapy institution with corticosteroids in immunosuppressive dose, there was rapid stabilization of the abdominal wound (within the first 48 hours). Despite the necrotic aspect in FO, surgical debridements were contraindicated from this moment on. The lesions’ treatment began to be carried out only with local hygiene, chemical debridement with hydrogel and daily dressings. While the wounds presented with exudate, we opted for dressings with calcium alginate with silver. After local improvement, kept non-adherent oily dressing. There was no further progression of necrosis or hyperemia areas. The wound showed gradual improvement, with the appearance of good-looking granulation tissue.

Concomitantly with the improvement of the abdominal wound, the patient presented evident clinical improvement. It evolved with normalization of heart rate and did not present more febrile episodes. Laboratory tests showed gradual improvement.

Associating the clinical evolution (positive therapeutic test) with the revised and suggestive anatomopathological exam, the diagnosis of gangrenous pyoderma with probable secondary infection was determined.

The patient remained hospitalized at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre until the wound was completely granulated, without any area of necrosis or secretion. Intravenous corticosteroid was replaced by prednisone 80mg/day during hospitalization, with a gradual reduction plan. Weekly outpatient care was organized (2x a week) with the plastic surgery team and the nursing team to maintain treatment and review the dressings after hospital discharge. Weaning from corticosteroid therapy was guided by the dermatology team. The patient was discharged clinically well, stable and with the lesions in great aspect.

Once diagnosed with Pyoderma gangrenosum, the patient was not submitted to wound reconstruction procedures with a skin graft because of the disease’s risk of reactivation. It was decided to close by the second intention, with the satisfactory aesthetic result given the condition’s severity. The patient obtained complete closure of the lesions approximately six months postoperatively, without presenting any functional limitation stemming from healing (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Pyoderma gangrenosum, although rare, should be known to all surgeons since its early diagnosis and correct treatment are essential to avoid serious and devastating aesthetic and functional sequelae. In the postoperative period, PG lesions are triggered by an erroneous and exacerbated immune stimulus, with the appearance of new and successive inflammatory lesions in the area of trauma, a phenomenon known as pathergy12. About 40% of cases of pyoderma gangrenosum occur after trauma or surgery13. It has been described as a postoperative complication of several medical specialties. In the context of plastic surgery, it has already been reported after breast surgeries (aesthetic and reconstructive), abdominoplasties and fasciocutaneous flaps.

This pathology’s diagnosis is usually delayed in the postoperative period since more common hypotheses (such as surgical wound infection or necrosis by tissue ischemia) are suggested before. The case report of this article corroborates this observation. In severe cases, although even rarer, Pyoderma gangrenosum can trigger systemic toxicity, with tachycardia, fever and other signs9. In this situation, as described in the above report, the confounding factors with severe infectious complications are even more difficult to differentiate. Unfortunately, the treatment of these two complications is quite different, and the erroneous diagnosis considerably delays the patient’s recovery. The correct diagnosis is mainly clinical, made by excluding other diseases and other complications. Laboratory tests are non-specific, as is histopathological analysis.

One should always pay no prior account of the patient’s surgical history, as PG lesions may be recurrent. Complete anamnesis, with an investigation of associated systemic diseases, can also be an important tool for differential diagnosis. However, approximately half of the cases are idiopathic and are not associated with other systemic comorbidities; in these, as well as the case described above, the correct diagnosis becomes even more challenging. The failure of antibiotic therapy, especially when broad-spectrum, and the progression of lesions after surgical debridement suggest alternative diagnostic hypotheses.

PG’s treatment is not well established, but the current consensus is the association of topical and systemic measures. Corticosteroid therapy is now the first line of treatment. Cyclosporine is considered the second line of treatment and can be used alone or in combination with corticosteroids, with increased antimicrobial benefit. Dapsone can be used as an alternative to corticosteroids and seems to have a good result in treating the disease and in the prevention of relapses14. Concerning topical measures, Vieira et al., in 201114 and Portinho et al., in 201415 have described the use of hyperbaric therapy, with a decrease in healing time.

In the case reported above, topical treatment was performed with hydrogel dressings, calcium alginate with silver and, later, non-adherent oily dressings. Systemic treatment consisted of intravenous corticosteroid therapy in immunosuppressive dose, in addition to adequate analgesia. Surgical debridements were contraindicated from the moment the pyoderma gangrenosum hypothesis was suggested. Subsequent reconstructive treatment with skin graft was not indicated by the risk of reactivation of the disease and the excellent evolution of the wound with the treatments instituted. The patient in question obtained complete closure of the wounds six months postoperatively, with the satisfactory aesthetic result and no functional sequelae. In the literature, several authors describe cases with complete healing only after two years of evolution.

It is extremely important to provide information and adequate patient guidance; she must understand that his disease has a chronic and recurrent character.

CONCLUSION

PG, although rare, should be considered as a differential diagnosis in cases of postoperative complications with skin loss and necrosis that do not respond to the initial measures of treatment, in addition to apparently infectious conditions that do not respond to the antibiotic therapies adopted. Early diagnosis and correct treatment are extremely important for reducing harm and sequelae to patients.

REFERENCES

1. American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAP). Aesthetic Plastic Surgery National Databank - Procedural statistics [Internet]. Garden Grove: ASAP; 2019; [acesso em 2020 Fev 10]. Disponível em: https://www.surgery.org/media/statistics

2. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS). ISAPS global statistics [Internet]. West Lebanon: ISAPS; 2020; [acesso em 2020 Fev 21]. Disponível em: https://www.isaps.org/medical-professionals/isaps-global-statistics/

3. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP). Pesquisas - Censo 2018 [Internet]. São Paulo: SBCP; 2018; [acesso em 2020 Fev 21]. Disponível em: http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/pesquisas/

4. Gemperli R, Mendes RRS. Complicações em abdominoplastia. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34:53-56.

5. Cullen TS. A progressively enlarging ulcer of the abdominal wall involving the skin and fat, following drainage of an abdominal abscess apparently of appendiceal origin. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1924;38(5):579-582.

6. Brusting LA, Goeckerman WH, O'Leary PA. Pyoderma (ecthyma) gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in 5 cases occurring in adults. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1930 Out;22(4):655-80.

7. Souza CS, Chioss MPV, Takada MH, Foss NT, Roselino AMF. Pioderma gangrenoso: casuística e revisão de aspectos clínicolaboratoriais e terapêuticos. An Bras Dermatol. 1999;74(5):465-72.

8. Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Jun;13(3):191-211.

9. Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009 Set;23(9):1008-17.

10. Meyer TN. Pioderma gangrenoso: grave e mal conhecida complicação da cicatrização. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plást. 2006;21(2):120-4.

11. Konopka CL, Padulla GA, Ortiz MP, Beck AK, Bitencourt MR, Dalcin DC. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review article. J Vasc Bras. 2013 Mar;12(1):25-33.

12. Fraga JCS, Valverde RV, Souza VL, Gamonal A. Pioderma gangrenoso: apresentação atípica. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81(3):305-8.

13. Rosseto M, Costa SC, Narváez PLV, Nakagawa CM, Costa GO. Pioderma gangrenoso em abdominoplastia: relato de caso. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(4):654-7.

14. Vieira WA, Barbosa LR, Martin LMM. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as an adjuvant treatment for pyoderma gangrenosum. An Bras Dermatol. 2011 Nov/Dez;86(6):1193-6.

15. Portinho CP, Miguel LMC, Morello ER, Herter AHR, Collares MVM. Tratamento de pioderma gangrenoso após mamoplastia redutora com imunossupressão e oxigenoterapia hiperbárica: relato de caso e revisão da literatura. Arq Catarin Med. 2014;43(Supl 1):17-9.

1 . Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Plastic Surgery Service, Porto Alegre, RS,

Brazil.

2 . Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, Department of Plastic Surgery, Porto

Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Isabel Cristina Wiener Stensmann, Rua Ramiro Barcelos, 2350, Santana, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Zip Code: 90035-007. E-mail: isabel.stensmann@gmail.com

Article received: March 19, 2020.

Article accepted: July 19, 2020.

Institution: Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil e Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Conflicts of interest: none

COLLABORATIONS

ICWS Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

CPP Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

GAPF Conception and design study, Data Curation

EMZ Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

MAJZ Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation

ACPO Final manuscript approval, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter