Original Article - Year 2021 - Volume 36 -

Reconstruction of the nasal subunits after tumor resection

Reconstrução das subunidades nasais após ressecção tumoral

ABSTRACT

Introduction: A majority of the nods present for reconstruction are secondary to tumor excision. The objective is to analyze the efficacy of the reconstructive technique used to cover the defect after tumor exeresis according to the affected nasal anatomical subunit.

Method: Retrospective study of the medical records of 118 patients submitted to resection of the nasal tumors at the Mário Penna Institute in Belo Horizonte/ MG from August 2012 to March 2017.

Results: Incidence was higher in women (56%) and whites (54.3%) average age of 71.3 years. A total of 125 tumors were resected, and 122 nose reconstructions were performed. Basal cell carcinoma (90.4%) was the most prevalent nonmelanoma skin tumor, the most frequent solid histological subtype (33.6%). The techniques for reconstruction of defects that affect only one nasal subunit were mostly using the bilobed flap (26.5%). In complex nose reconstructions, the bilobed myocutaneous flap (45.8%) with extension to a glabella region (encompassing the procerus, corrugator and nasal muscles) was the most used, mainly in defects in the lower third of the nose. About 78 patients had cancer follow-up of more than one year, and 82 total sin tumors were evaluated. Seven (8.5%) Tumors retreated even after complete resection, and, among the six patients with compromised margins, only one (1.2%) relapsed.

Conclusion: The reconstructive techniques used were effective for treating nasal skin cancer and coverage of defects after resection, with low rates of complication and recurrence.

Keywords: Nose; Nasal Neoplasms; Basal cell carcinoma; Plastic surgery; Surgical flaps.

RESUMO

Introdução: A maioria dos defeitos nasais que se apresentam para reconstrução são secundários à excisão tumoral. O Objetivo é analisar a eficácia da técnica reconstrutora utilizada para a cobertura do defeito após exérese tumoral de acordo com a subunidade anatômica nasal acometida.

Método: Estudo retrospectivo dos prontuários de 118 pacientes que durante o período de agosto de 2012 a março de 2017 foram submetidos à ressecção dos tumores nasais no Instituto Mário Penna em Belo Horizonte/MG.

Resultados: A incidência foi maior em mulheres (56%) e brancos (54,3%) com idade média de 71,3 anos. Foram ressecados 125 tumores e realizadas 122 reconstruções nasais. O carcinoma basocelular (90,4%) foi o tumor de pele não melanoma mais prevalente, sendo o subtipo histológico sólido (33,6%) o mais frequente. As técnicas para reconstrução dos defeitos que acometiam apenas uma subunidade nasal foram em sua maioria utilizando o retalho bilobado (26,5%). Nas reconstruções nasais complexas, o retalho miocutâneo bilobado (45,8%) com extensão para a região glabelar (englobando os músculos prócero, corrugador e nasal) foi o mais utilizado, principalmente em defeitos no terço inferior do nariz. Cerca de 78 pacientes apresentaram acompanhamento oncológico superior a um ano, sendo avaliados 82 tumores no total. Sete (8,5%) tumores recidivaram mesmo após ressecção completa e, entre os seis pacientes com margens comprometidas, apenas um (1,2%) recidivou.

Conclusão: As técnicas reconstrutoras utilizadas foram eficazes para o tratamento do câncer de pele nasal e cobertura dos defeitos após ressecção, apresentando baixos índices de complicação e recidiva.

Palavras-chave: Nariz; Neoplasias nasais; Carcinoma basocelular; Cirurgia plástica; Retalhos cirúrgicos

INTRODUCTION

Skin cancer is commonly located on the face, especially in the nasal region1. About 75% of nonmelanoma skin tumors occur in the head and neck, 30% are located in the nose2. Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma are major clinical-surgical indications of oral reconstructions3.

The skin flaps used for nasal reconstruction have great versatility in their application4. The reconstruction’s success will depend on the location, size and depth of the defect, the availability of the donor area and, more importantly, the surgeon’s options in terms of material, method and approach5.

Burget and Menick, in 19856, revolutionized nasal reconstruction surgery with the introduction of the concept of aesthetic subunits of the nose based on differences in elasticity, color, contour and skin texture, which contributes to the refinement of nasal surgery.

Due to nasal architecture’s location and complexity, a reconstruction of the nose represents a challenge to the plastic surgeon. The particular characteristics of the skin that lines the area and the multiple concavities and convexities existing on its surface must be respected to restore the normality of form and function 7,8. A minimal subtle change in structure can have a profound impact on appearance and architecture. Thus, the treatment involves restorative and aesthetic issues, aiming to cure and the lowest possible deformity1,9.

OBJECTIVES

According to the affected nasal anatomical subunit, to analyze the efficacy of the reconstructive technique used to cover the defect after tumor exeresis.

METHODS

It consists of a retrospective study of the medical records of 118 patients who, from August 2012 to March 2017, were submitted to resection the nasal tumors at the Mário Penna Institute in Belo Horizonte/MG. The research was submitted to the institution’s ethics and research committee (CEP), where the study was conducted, being approved with CAAE 33431020.8.0000.5121 and opinion number 4.182.872.

There were included in the study Patients with primary nasal tumor with no history of previous resection, whose anatomopathological diagnosed nonmelanoma tumor (basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma). Patients who did not fit these criteria were excluded from the study. Regarding oncologic follow-up, patients who did not have a postoperative follow-up for more than 12 months were also excluded. As substance losses secondary to oncologic surgery were mapped according to the anatomical subunits3,9 described by Burget and Menick (1985)6.

RESULTS

Epidemiological profile of patients

Of the 119 patients studied, the mean age was 71.3 years, ranging from 41 to 93 years. A majority of the sample consisted of whites (54.3%) with females’ predominance (56%). Only 17.8% of the patients were from the capital, the majority of whom were from cities in the interior of Minas Gerais.

Epidemiological profile of tumors

In total, 125 tumors were resected, with 53.6% already presenting ulceration at the initial clinical examination. One main clinical-surgical indication for nasal reconstruction was basal cell carcinoma, responsible for 90.4% of cases, with the nodular solid histological subtype (33.6%) the most frequent (Table 1).

| Histology | n=125(%) |

|---|---|

| BCC | 113 (90.4%) |

| SCC | 12 (9.6%) |

| Histological subtype | n=125 (%) |

| BCC nodular solid | 42 (33.6%) |

| Sclerodermiform BCC | 22 (17.6%) |

| BCC nodular adenoid | 20 (16%) |

| Multicenter superficial BCC | 8 (6.4%) |

| BCC micronodular | 6 (4.8%) |

| PIGMENTED BCC | 5 (4%) |

| Metatypical BCC | 5 (4%) |

| Basosquamous BCC | 3 (2.4%) |

| Keratotic BCC | 2 (1.6%) |

| Well differentiated CCE | 8 (6.4%) |

| Moderately differentiated CCE | 4 (3.2%) |

Regarding the degree of tumor invasion, skin involvement alone was predominant, affecting 81.6% of the cases. The sclerodermiform subtype (23%) and ulcerated solid (23%) prevailed in tumors with deep invasion at the subcutaneous, muscular or cartilage layer level. In total, 17 (17%) cases had compromised microscopic surgical margins, with 6 (35.3%) surgical reapproaches to enlarge the margins, with no residual tumor in the anatomopathological area after enlargement.

The nasal ala (36.7%) was the most involved subunit, followed by the nasal tip (28.6%). About 24 (20.3%) patients had complex tumors that affected more than one aesthetic subunit, with the dorsal association with the nasal tip (33.3%) being the most affected concomitant subunits. Only one patient had three affected nasal aesthetic subunits located in the distal third of the nose (Table 2).

| subunit nasal | n=98 (%) | Type of reconstruction | n=98 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wing | 36 (36.7%) | Nasogenic | 22(61.1%) |

| Bilobed | 5(13.8%) | ||

| Frontal | 3 (8.3%) | ||

| Primary synthesis | 2 (5.6%) | ||

| Total graft | 2 (5.6%) | ||

| Rhomboid | 1 (2.8%) | ||

| Esser | 1 (2.8%) | ||

| Tip | 28 (28.6%) | Bilobed | 14 (50%) |

| Primary synthesis | 8 (28.5%) | ||

| Frontal | 2 (7.1%) | ||

| Nasogenic | 1 (3.6%) | ||

| Glabellar | 1 (3.6%) | ||

| Retail advancement | 1 (3.6%) | ||

| Total graft | 1 (3.6%) | ||

| Dorsum | 26 (26.6%) | Primary synthesis | 7 (26.9%) |

| Bilobed | 5 (19.3%) | ||

| Glabellar | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| Total graft | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| Retail advancement | 3 (11.5%) | ||

| Rhomboid | 2 (7.7%) | ||

| frontal | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Lateral | 7 (7.1%) | Bilobed | 2 (28.55%) |

| Retail advancement | 2 (28.55%) | ||

| Primary synthesis | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Rhomboid | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Glabellar | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Columella | 1 (1%) | frontal | 1 (100%) |

Reconstruction of nasal defects after tumor resection

After surgical resection, the average size of the defects to be reconstructed was 2.5x1.8cm and were operated with surgical margins ranging from 2mm to 1cm. The presence of ulcers increased the planning of surgical margins by 2 mm. In general, the techniques for reconstructing defects that affected only one nasal subunit were mostly using the bilobed flap (26 cases, 26.5%), followed by the nasogenian flap (23 cases, 23.4%). The flaps used specifically for each nasal subunit will be described in more detail below (Table 2).

Nasal ala reconstruction

For the specific reconstruction of the nasal ala, the most used flap was the nasogenian flap in 22 (61.1%) cases, followed by bilobed (13.8%) and frontal flap (8.3%). Primary synthesis (5.6%) and total skin graft (5.6%) were performed in 2 patients each. The Esser flap (2.8%) and rhomboid (2.8%) were used in only one patient. Two patients received a conchal cartilage graft to repair the nasal ala after tumor resection.

Reconstructions of the nasal tip

At the nasal tip, the most used reconstruction was with a bilobed myocutaneous flap (50%) encompassing the proximal, corrugator and nasal muscles, followed by the primary closure technique after spindle resection (28.5%)

Dorsal nasal reconstructions

For dorsal nasal tumors, seven primary closures were performed, corresponding to 26.9% of cases. Then, the bilobed flap appears as the second most frequent flap, and it was performed in 19.3% of cases.

Reconstruction of the lateral wall

The bilobed flap (28.5%) and V-Y advancement flap (28.5%) were the most used in reconstructing defects in the lateral wall. Primary synthesis (14.3%) was also an option used, as were rhomboid (14.3%) and glabellar (14.3%) flaps.

Columella reconstruction

In our study, only one patient presented isolated tumor involvement in the columella region, and its reconstruction was performed with a myocutaneous flap of the frontal muscle and septal cartilage graft.

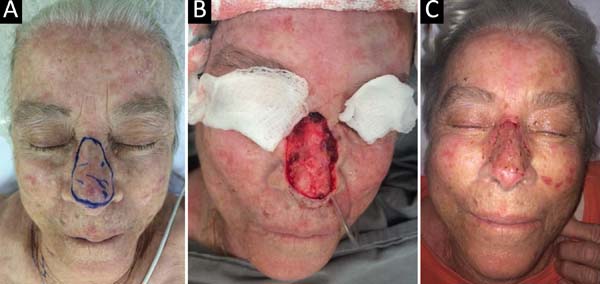

Complex nose reconstructions

In the case of complex nose reconstructions (involvement of more than one aesthetic subunit), the bilobed myocutaneous flap (45.8%) with extension to a glabella region (encompassing the procerus, corrugator and nasal muscles) was the most used in the complex defects of the lower third of the nose (Figure 1).

One patient with tip involvement and nasal ala required a septal cartilage graft associated with a bilobed flap for nasal ala repair after tumor resection.

The nasogenic myocutaneous flap (16.6%) covering the superficial musculoaponeurotic system of the superficial face (SMAS) and major and minor zygomatic muscles was the second most used, is intended mainly for reconstructions that covered the lateral wall with the nasal alas (Figure 2). The frontal myocutaneous flap (16.6%) was used in complex reconstructions that covered the distal nasal tip/columella and in a case of compromised three nasal aesthetic subunits of the distal portion of the nose (Table 3).

| >01 Nasal subunit | n=24 (%) | Type of reconstruction |

n=24(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsum + Tip | 8 (33.3%) | Bilobado | 4 (50.0%) |

| Frontal | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Romboide | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Rintala | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Enxerto total | 1( 12.5%) | ||

| Lateral + Wings | 7 (29.1%) | Bilobado | 3 (42.9%) |

| Nasogeniano | 3 (42.9%) | ||

| Enxerto total | 1 (14.2%) | ||

| Tip + Wing | 6 (25%) | Bilobado | 3 (49.9%) |

| Frontal | 1 (16.7%) | ||

| Nasogeniano | 1 (16.7%) | ||

| Enxerto total | 1 (16.7%) | ||

| Columella + Tip | 2 (8.4%) | Frontal | 1 (50%) |

| Bilobado | 1 (50%) | ||

| Tip + Right nasal wing + Left nasal wing | 1(4.2%) | Frontal | 1 (100%) |

Alternatively, in a single case with columella involvement associated with the tip, the myocutaneous bilobed flap was used for tip reconstruction and associated with an advanced flap with the columella’s primary synthesis after partial exeresis of the alar cartilage. The flap provided adequate volume without the need for cartilaginous grafts (Figure 3).

Only three cases were submitted to total skin grafts, with a supraclavicular region as a donor area (Figure 4).

Postoperative complications

In the 122 reconstructive procedures performed, there were only five surgical complications (4%). One principal was mild epidermolysis after bilobed flap but without partial or total loss of the flap. There was only partial frontal flap necrosis in the columella region. Regarding skin grafts, one case evolved with necrosis and partial loss of the partial graft in the nasal tip. Only one patient presented infection and small surgical wound dehiscence after primary synthesis in the nasal tip.

Among the 125 resected tumors, about twelve (9.6%) tumors had compromised surgical margins, evidenced in the anatomopathological exam. Of these, six (50%) tumors underwent a reapproach to expand the margin, and the remaining patients not approached had narrow surgical margins.

Postoperative oncological follow-up

In total, 78 patients underwent oncological follow-up for more than 12 months, with an average outpatient follow-up time of 27.4 months after the surgical procedure, with a standard deviation of 11.2 months.

Approximately 82 tumors were monitored, six (7.3%) of which had narrow surgical margins in the anatomopathology.

During the period, eight (9.7%) tumors evolved with recurrence. Among these tumors, seven (8.5%) presented recurrence even after complete resection, with the average time for lesions to appear 24 months (standard deviation: 13.4) after initial surgical procedure.

Only one (1.2%) tumor evolved with recurrence in patients with narrow margins, and its clinical diagnosis occurred 14 months after initial tumor resection. The other cases that remained in the follow-up did not present recurrence (Table 4). In recurrent tumors, ulcerated nodular solid BCC was the predominant histological subtype (42.9%) Squamous cell carcinoma (28.5%).

| Tumors n=82 (100%) | Relapse n=8 (9.7%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Free margins | 76 (92.7%) | 7 (8.5%) |

| Compromised margins (narrow) | 6 (7.3%) | 1 (1.2%) |

DISCUSSION

Due to its central location on the face and functional importance, nasal reconstruction represents a significant plastic surgeon challenge. Most nasal defects that appear for reconstruction are secondary to tumor excision10. BCC and SCC represent the first and second types of cancer with the highest incidence and have cure rates above 90% when treated in the initial phase1,10. In our sample, 90.4% of the nasal tumors were of the CBC type and only 9.6% of the CCE.

The average age of patients included in this study (71.3 years) follows the literature since most individuals with skin cancer are older than 60 years, with a higher prevalence in the 7th decade of life1. Most patients were Caucasian (54.3%) and female (56%). Although it is well known in the literature that skin tumors tend to occur more frequently in male patients, especially in the nose4, current studies show a time trend of increasing the proportion of women in relation to men11.

The histological subtypes most frequently found were solid BCC and sclerodermiform, and most patients already had ulceration on clinical examination, requiring greater surgical margins. Also, sclerodermiform BCC is generally a histological subtype present in cases with local aggressiveness1, which was demonstrated by its greater frequency in an invasion of deep layers (subcutaneous, cartilage and muscle) together with solid ulcerated and adenoid BCC. Thus, these tumors need an elaborate reconstruction and should preferably be performed in referral centers. According to the world literature, the committed margin index was 9.6%, varying from 4% to 18.2% 12.

Among the twelve tumors with compromised margins,6 (50%) surgical approaches for enlargement were performed. All tumors reopened had free margins in the anatomopathological. Similar data are found in the literature in which new surgical interventions are performed in 30% to 74.7% of tumors with incomplete resection9,13-15. The decision to perform a new operation on resected tumors with compromised margins is not unanimous9,16. A new surgical procedure’s risks and benefits must be assessed individually since the risk of recurrence after complete tumor resection is also present, reaching up to 14% 17,18, with a 9.7% recurrence being found in our sample. This fact provides the medical option’s freedom when choosing conservative treatment for patients with comorbidities and increased surgical risk9.

The integrity of the aesthetic subunits of the nose is fundamental in maintaining the harmony of facial features. A nasal ala was the most compromised aesthetic subunit, followed by the nasal tip. This result is not consistent with the literature’s data, which show greater appearance in the nasal dorsum3,19.

However, in studies conducted in cancer treatment reference centers, it is possible to perceive in the sample a higher incidence of lesions in the lower third of the nose because these require more complex reconstructions19,20.

The choice of the most appropriate flap was based on the affected nasal subunits, shape and orientation of the defects after tumor surgical resection. The defects of the upper and middle thirds (dorsal and lateral) were corrected mainly with bilobed, glabellar flaps and primary synthesis. In dorsal nasal reconstructions, spindle resection with primary closure was the most used (26.9%), followed by the bilobed flap (19.3%). Due to the greater availability of skin, the use of primary closure for small defects and advancement flaps and transposition for larger defects are quite common in the dorsal region21,22. The bilobed flap (28.5%) and the V-Y advancement flap (28.5%) were the most used in the reconstruction of lateral wall defects.

In the lower third (tip and wing), the preference was for single-time reconstruction with a bilobed myocutaneous flap and nasogenians. For the nasal ala’s specific reconstruction, the most used flap was the nasogenian flap (61.1%). The nasogenian flap is fast to execute, and, besides, it has the advantages of having a color and texture similar to that of the nose, and its location allows a transposition with reduced deformity of the donor site and a slight scar7,23. They are flaps of extreme versatility, being more used to correct defects between 8-2mm24.

At the nasal tip, the most used reconstruction was with a bilobed myocutaneous flap (50%). The bilobed flap is often used for nasal reconstructions of the dorsum and lower third of the nose25. When encompassing the proximal, corrugating and nasal muscles, it was possible to cover major defects; but, as disadvantages, when involving the glabellar region, they present a greater scar and a reduction in the distance between the eyebrows.

In complex nasal reconstructions in the lower third, the bilobed myocutaneous flap (45.8%) was more frequent. This flap is described in the literature and is useful for defects in the lower part of the nose measuring 0.5-1.5cm5; however, by encompassing the proximal, corrugator and nasal muscles, it allowed a greater arc of rotation and flap volume with better filling and covering defects of up to three centimeters. In addition, the design allows for a greater arc of rotation and a sufficiently large size, also allowing its use for defects located in the upper region of the columella simultaneously with defect of the tip. Thus, it was possible to reconstruct in a single time and with less morbidity when compared to the frontal flap. The frontal myocutaneous flap was reserved for complex reconstructions that covered the distal nasal tip/distal columella and in a case of involvement of 3 nasal aesthetic subunits of the distal portion of the nose.

CONCLUSION

The present study adopted the principles of nasal reconstruction added to aesthetic subunits’ concepts, aiming to respect the nasal contour and anatomy. The reconstructive techniques used were effective for treating nasal skin cancer and coverage of defects after resection, with low rates of complication and recurrence. This study can help guide surgeons in the face of the wide range of flaps available, assisting in deciding the most appropriate nasal reconstruction without compromising function and providing satisfactory aesthetic results in the repair of each nasal subunit and in complex defects.

REFERENCES

1. Santos ABO, Loureiro V, Araújo Filho VJF, Ferraz AR. Estudo epidemiológico de 230 casos de carcinoma basocelular agressivos em cabeça e pescoço. Rev Bras Cir Cabeça Pescoço. 2007 Dez;36(4):230-3.

2. Wolfswinkel EM, Weathers WM, Cheng D, Thornton JF. Reconstruction of small soft tissue nasal defects. Semin Plast Surg. 2013 Mai;27(2):110-6.

3. Soares VR. Reconstrução de nariz em neoplasias. Rev Bras Med. 1975;32(1):3-9.

4. Guo L, Pribaz JR, Pribaz JJ. Nasal reconstruction with local flaps: a simple algorithm for management of small defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):130e-9e.

5. Neligan PC, Rodriguez ED. Cirurgia Plástica: cirurgia craniomaxillofacial e cirurgia de cabeça e pescoço. 3ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier; 2015.

6. Burget GC, Menick FJ. The subunit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985 Ago;76(2):239-47.

7. Thornton JF, Weathers WM. Nasolabial flap for nasal tip reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Set;122(3):775-81.

8. Lambert RW, Dzubow LM. A dorsal nasal advancement flap for off-midline defects. J AM Acad Dermatol. 2004 Mar;50(3):380-3.

9. Veríssimo P, Barbosa MVJ. Tratamento cirúrgico dos tumores de pele nasal em idosos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(2):219-33.

10. Scanavini Junior RC, Martins AS, Tincani AJ, Altemani A. Fatores prognósticos do carcinoma espinocelular cutâneo de cabeça e pescoço. Rev Bras Cir Cabeça Pescoço. 2007;36(4):226-9.

11. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância. Estimativa 2020: incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Ministério da Saúde/INCA; 2019.

12. Tan PY, Ek E, Su S, Giorlando F, Dieu T. Incomplete excision of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: a prospective observational study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Set;120(4):910-6.

13. Bariani RL, Nahas FX, Barbosa MV, Farah AB, Ferreira LM. Basal cell carcinoma: an updated epidemiological and therapeutically profile of an urban population. Acta Cir Bras. 2006 Mar/Abr;21(2):66-73.

14. Kumar P, Orton CI, McWilliam LJ, Watson S. Incidence of incomplete excision in surgically treated basal cell carcinoma: a retrospective clinical audit. Br J Plast Surg. 2000 Out;53(7):563-6.

15. Hallock GG, Lutz DA. A prospective study of the accuracy of the surgeon's diagnosis and significance of positive margins in nonmelanoma skin cancers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001 Abr;107(4):942-7.

16. Griffiths RW. Audit of histologically incompletely excised basal cell carcinomas: recommendations for management by re-excision. Br J Plast Surg. 1999 Jan;52(1):24-8.

17. Farhi D, Dupin N, Palangié A, Carlotti A, Avril MF. Incomplete excision of basal cell carcinoma: rate and associated factors among 362 consecutive cases. Dermatol Surg. 2007 Out;33(10):1207-14.

18. Nagore E, Grau C, Molinero J, Fortea JM. Positive margins in basal cell carcinoma: relationship to clinical features and recurrence risk. A retrospective study of 248 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003 Mar;17(2):167-70.

19. Souza Filho MV, Kobig RN, Barros PB, Dibe MJA, Leal PRA. Reconstrução nasal: análise de 253 casos realizados no Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2002;48(2):239-45.

20. Moura BB, Signore FL, Buzzo TE, Watanabe LP, Fischler R, Greitas JOG. Reconstrução nasal: análise de série de casos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2016;31(3):368-72.

21. Zimbler MS. The dorsal nasal flap for reconstruction of large nasal tip defects. Dermatol Surg. 2008 Abr;34(4):571-4.

22. Rohrer TE, Bhatia A. Transposition flaps in cutaneous surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2005 Ago;31(2):1014-23.

23. El-Marakby HH. The versatile naso-labial flaps in facial reconstruction. J Egyp Natl Canc Inst. 2005 Dez;17(4):245-50.

24. Romaní J, Yébenes M. Repair of surgical defects of the nasal pyramid. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007 Jun;98(5):302-11.

25. Kimyai-Asadi A, Alam M, Goldberg LH, Peterson SR, Silapunt S, Jih MH. Efficacy of narrow-margin excision of well-demarcated primary facial basal cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Set;53(3):464-8.

1. Fundação Benjamim Guimarães, Hospital da Baleia, Plastic Surgery Service, Belo

Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

2. Instituto Mário Penna Institute, Plastic Surgery Service, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Camila Carvalho Cavalcante Marinho, Rua dos Timbiras, 1228, Apto 1903, Boa Viagem, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil Zip Code: 30140-064 E-mail: camila_ccavalcante@hotmail.com

Article received: August 31, 2020.

Article accepted: January 10, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none

COLLABORATIONS

CCCM Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

MLM Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision

RCL Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Investigation

CJR Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation

KVTP Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation

CFR Final manuscript approval, Investigation

SFG Final manuscript approval, Investigation

HLRR Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Supervision, Validation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter