Original Article - Year 2021 - Volume 36 -

Skin bank of Curitiba, Brazil: epidemiology of donors and recipients

Banco de pele de Curitiba, Brasil: epidemiologia de doadores e receptores

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Homologous skin grafting may represent the difference between the life and death of large burned patients. Its use consists of a precious treatment when there is no availability of autologous graft. The tissue banks were created to perform the processing and storage of the allogenous skin. The objective is to analyze the epidemiological profile of skin donors and recipients from the skin bank of the Hospital Universitário Evangélico Mackenzie (HUEM) and its productivity, from its inauguration in 2013 to 2019.

Methods: Consultation of annual reports for the seven years.

Results: The skin of 187 donors was captured, of which 61% were men and 39% were women. The mean age was 41.07 years. The number of donors averaged 21.3 per year. A total of 201,000cm2 of viable tissue were collected, which resulted in 3,770 skin slides. Since 2013, 325 allogenous grafts have been performed at HUEM that have benefited 194 people. The mean age of patients receiving the skin was 34.67 years. Most of the skin captured, processed, and stored by the HUEM bank (about 91%) was used in grafting carried out in the institution itself.

Conclusion: The HUEM skin bank provided allografts that benefited 194 people in 7 years of operation. Most donors and recipients were male and approximately 40 years old. The number of captures performed by this skin bank was compatible with that of other institutions in Brazil.

Keywords: Skin; Plastic surgery; Skin transplant; Burns; Tissue donors; Tissue transplant.

RESUMO

Introdução: A enxertia homóloga de pele pode representar a diferença entre a vida e a morte de pacientes grandes queimados. Sua utilização consiste em um tratamento precioso quando não há a disponibilidade do enxerto autólogo. Os bancos de tecidos foram criados para realizar o processamento e armazenamento da pele alógena. O objetivo é analisar o perfil epidemiológico de doadores e receptores de pele do banco de pele do Hospital Universitário Evangélico Mackenzie (HUEM) e a sua produtividade, desde a inauguração em 2013 até 2019.

Métodos: Consulta aos relatórios anuais do período de sete anos.

Resultados: Captou-se a pele de 187 doadores, dos quais 61% eram homens e 39%, mulheres. A idade média foi de 41,07 anos. O número de doadores atingiu a média de 21,3 por ano. Foram coletados, no total, 201.000cm2 de tecido viável, que resultaram na produção de 3.770 lâminas de pele. Desde 2013, foram realizados no HUEM, 325 enxertos alógenos que beneficiaram 194 pessoas. A idade média dos pacientes que receberam a pele foi de 34,67 anos. A maior parte da pele captada, processada e armazenada pelo banco do HUEM (cerca 91%) foi utilizada em enxertias realizadas na própria instituição.

Conclusão: O banco de pele do HUEM disponibilizou aloenxertos que beneficiaram 194 pessoas em 7 anos de funcionamento. Em sua maioria, os doadores e receptores eram do sexo masculino e tinham, aproximadamente, 40 anos de idade. O número de captações realizadas por este banco de pele foi compatível com o de outras instituições do Brasil.

Palavras-chave: Pele; Cirurgia plástica; Transplante de pele; Queimaduras; Doadores de tecidos; Transplante de tecidos.

INTRODUCTION

Homologous skin grafting may represent the difference between the life and death of large burned patients. Its use consists of a precious treatment when an autologous graft is not available1. Allogeneic skin grafting has been used since the nineteenth century, and after this long period, this practice proved to be a safe and effective procedure in the management of burns2.

Although there are isolated reports in the literature, historically, the first to describe epidermal grafts in skin losses was Reverdin in 18693. The procedure consisted of elevating the donor area’s skin with a needle, forming small peaks, whose ridge was cut horizontally, and the extracted fragment was then transferred to the receiving area4. However, the use of skin allografts specifically for burn treatment was described only in 1881 by Girdner5.

The loss of skin integrity promotes fluid loss, infections, hypothermia, impaired immunity, hypovolemia, and pain, among other complications2-4. In patients with burns of great body extension and scarcity of donor area, the surgeon may opt for allogenous skin transplantation2-4 this, in turn, reduces the loss of fluids and proteins by the injured areas, acts as a physical barrier against germs, modulates the wound bed to stimulate the physiological healing process and promotes analgesia6, reducing morbidity and mortality2.

Despite the advantages of using allogenous grafts, tissue transplantation is not without risks, the main one being the transmission of infectious diseases. The tissue banks were created to perform the processing and storage of the allogenous skin. These banks operate through standards that ensure the tissue’s safety and quality, from its capture to the material’s distribution. This rigor is essential to ensure that skin transplantation is performed safely.

In 1997, through Law No. 9,4347, human organ and tissue transplantation was regulated in Brazil. The law establishes that the removal of tissues, organs, or parts of the human body post-mortem can only be performed after a diagnosis of brain death, confirmed by two physicians not participating in the removal and transplantation team, based on predefined clinical and technological criteria6. Since 2001, after Law No. 10,2118, there is a need for an informed consent form, with family consultation to authorize the donation.

Law No. 2,268 of 20179, established that both the uptake and transplantation of organs and tissues could only be performed by specialized medical-hospital teams and institutions registered with the state health departments and the National Transplant System (SNT)8.

The Hospital Universitário Evangélico Mackenzie (HUEM)’s skin bank was inaugurated in June 2013, with its own facilities according to the standards of the SNT and, since then, performs collection and storage of skin in glycerol 90%6.

Skin donors are divided into two categories: brain death donors, who are multi-organ donors and comprise almost all skin bank donors, and donors in cardiorespiratory arrest10.

In 2019, according to statistics from the Brazilian Association of Organ Transplants (ABTO), the rate of organ and tissue donors increased by 6.5%. They stood out with notification rates of potential donors, the Federal District and Paraná, with a donation rate higher than 50% and with a family authorization rate higher than 70%. These values represent suitable donation parameters and have been used as a model by other states9.

Regarding cell and tissue transplants registered in 2019, there were 10,418 bone donors, 14,943 corneas, 3,805 bone marrow, and only 130 skin donors. However, there was an increase of more than 100% in effective donors compared to 2018, when 62 skin donors were registered11.

OBJECTIVES

Analyze the epidemiological profile of skin donors and recipients from the skin bank of the Hospital Universitário Evangélico Mackenzie (HUEM) and its productivity, from its inauguration in 2013 to 2019.

METHODS

For epidemiological analysis of the skin bank of the HUEM, a consultation was made to the annual reports of the seven-year period (2013 to 2019), whose completion is part of the bank’s routine. These reports contain information on donors, gender, date of donation, captured skin area (cm2), available skin area (cm² and slides), area of donor skin (cm2), and data on tissue distribution.

The present study obtained approval by the research ethics committee of the Mackenzie Presbyterian Institute, under opinion number: 32582620.6.0000.0103/2020.

RESULTS

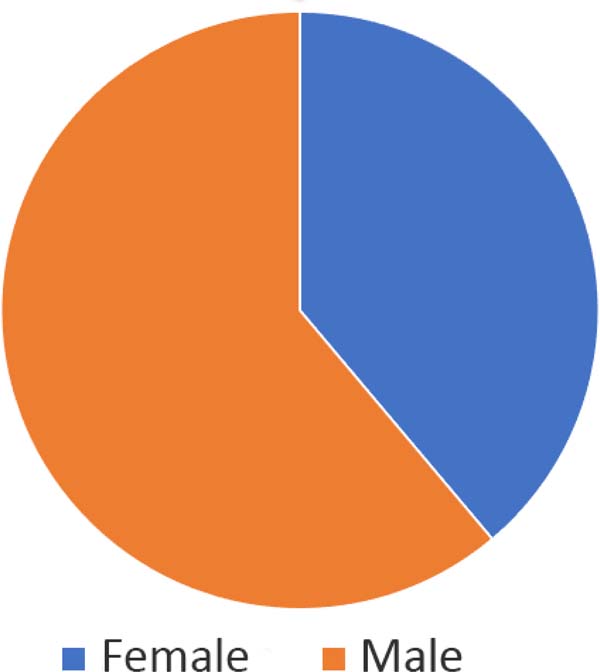

Between 2013 and 2019, skin uptake was performed from 187 donors, of which 114 (61%) were males and 73 (39%) females (Figure 1). These patients’ mean age was 41.07 years, with a registered minimum age of 16 years and maximum age of 60 years.

The number of donors averaged 21.3 per year. In 2015, there was a maximum peak of 29 skin donations and, in 2019, the lowest number recorded, only ten donors (Table 1). Of the total uptake, the tissues of 149 (79.7%) donors were used in transplants, and 38 (20.3%) were discarded for various causes, such as bacterial contamination.

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 14 | 31 | 29 | 27 | 26 | 12 | 10 |

During seven years of operation of the HUEM skin bank, 201,000cm2 of viable tissue were collected, resulting in the production of 3,770 skin slides. On average, 1,350.02cm2 of tissue were removed from each donor, corresponding to approximately 25.3 tissue slides. The smallest area obtained from a patient was 407.9cm2 of skin, while the largest area corresponded to 2,720cm2. More than 90% of the collections performed included the dorsum regions, trunk, and anterior and posterior parts of the lower limbs.

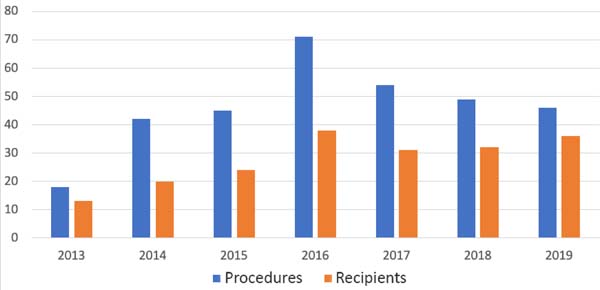

Tissue samples collected from a single donor could be used by about 2.6 recipients on average, with maximum utilization of 8 recipients per donor. On average, each recipient used 19.43 skin slides and underwent about 1.68 grafting procedures, performed mainly in burned patients. The year in which procedures were performed the most was 2016, with 71 operations in 38 receivers. The least busy year was 2013, with 18 procedures in 13 receivers. The annual mean of procedures was 46.43 (Figure 2).

Since 2013, 325 allogenous grafts have been performed at HUEM that have benefited 194 people. Of these recipients, 124 (63.9%) were male, and 70 (36.1%) the feminine. The mean age of patients receiving the skin was 34.67 years, with a minimum age of 1 year and a maximum of 63 years.

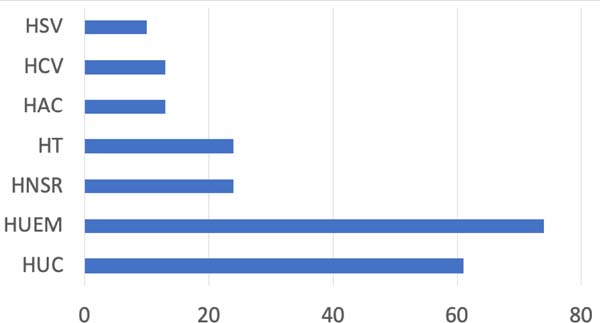

Tissue uptake was performed mainly in the HUEM itself, accounting for 74 collections. There were also captures in other locations, Hospital Universitário Cajuru (HUC) with 61 collections, Hospital do Trabalhador (HT) with 24 collections, Hospital Nossa Senhora do Rocio (HNSR) with 24 captures, Hospital da Cruz Vermelha (HCV), and Hospital Angelina Caron (HAC) with 13 captures each, in addition to the Hospital São Vicente (HSV) with 10 collections (Figure 3).

Most of the skin captured, processed, and stored by the HUEM bank (about 91%) was used in grafting performed in the institution itself, in the plastic and burned surgery sector. Other hospitals in Paraná performed 7% of the operations. Only 2% of these procedures were completed outside the state.

DISCUSSION

Compared to a previous study conducted at the same institution in 2013, HUEM remains the main hospital for tissue collection in Curitiba and the metropolitan region. However, its percentage participation was reduced from 44%6 to 28% due to the increase in other services’ contribution. The mean age of donor patients increased from 3612 to 41 years, and the minimum age (16) and maximum age (60) remained the same6-12. The minimum amount of tissue removed from a single donor remained similar (422.2 to 407.9cm2). However, the maximum amount of tissue removed increased from 1,252 (in2013) to 2,720 cm2,6-12 on the years of this study.

In 2019, the average amount of skin collected was 1,350.02cm2 per donor, surpassing data from 2013, when 1,252.59cm2 was recorded. The HUEM numbers are similar to the Porto Alegre skin bank, which obtained an average of 1,364.46cm2 between 2008 and 201013. This amount is still lower than that recorded in international banks, such as Helsinki, which captures 3,062cm2 of skin per donor, the smallest amount of a single donor being 1,655 cm2,14.

Regarding the recipients, men continue to have a higher prevalence (63.9%), as demonstrated in 2013 study6, when they corresponded to 66.7%. According to the research previously done in the same service, the average number of transplants performed per patient was 1.736-12 in 2013. This data is similar to that obtained in this research (2013 to 2019), which showed an average of 1.68 transplants per patient.

During these seven years of operation, the HUEM skin bank benefited 194 patients. HUEM continues to be the primary institution in performing tissue transplantation in Paraná. In 2013, still under the name Hospital Universitário Evangélico de Curitiba (HUEC), it covered 88.5% of skin transplants performed6-12 and is currently responsible for 91% of these procedures.

HUEM’s skin bank performs an average of 21.3 captures per year. This number is similar to that found in the Hospital de Clínicas de São Paulo’s tissue database, which recorded an average of 25.3 captures per year between 2001 and 200610. Between 2001 and 2008, the Helsinki skin collection center collected tissue from 7 to 20 donors, with an annual average of 14.414.

CONCLUSION

The HUEM skin bank provided allografts that benefited 194 people in 7 years of operation. Most donors and recipients were male and approximately 40 years old. The number of captures performed by this skin bank was compatible with that of other institutions in Brazil.

REFERENCES

1. Schiozer W. Banco de pele no Brasil. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2012;11(2):53-5.

2. Rech DL, Chem E, Milani AR, Minuizzi Filho ACS, Falcão TC, Ely PB. Rotina do banco de pele Dr. Roberto Corrêa Chem no processamento de pele de doador cadáver. Arq Catarin Med. 2012;41(Supl 1):123-5.

3. Reverdin JJ. Greffe épidermique, expérience faite dans le service de M. le Docteur Guyon à l'hôpital Necker. Bull Soc imp Chir Paris. 1869;3(10):511-5.

4. Mélega JM, Viterbo F, Mendes FH. Cirurgia plástica: os princípios e a atualidade. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2011.

5. Girdner JH. Skin grafting with graft taken from the dead subject. Med Rec. 1881;20:119-20.

6. Maschietto SM, Calomeno LH, Nigro M, Matioski A, Bonato FT. Relato do primeiro ano de experiência do banco de pele do Hospital Universitário Evangélico de Curitiba. Arq Catarin Med. 2015;44(1):22-7.

7. Lei n°9.434, de 04 de fevereiro de 1997 (BR). Dispõe sobre a remoção de órgãos, tecidos e partes do corpo humano para fins de transplante e tratamento e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF), 4 fev 1997: Seção 1: 1; [acesso em 2021 Mar 02]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9434.htm

8. Lei no 10.211, de 23 de março de 2001 (BR). Altera dispositivos da Lei no 9.434, de 4 de fevereiro de 1997, que "dispõe sobre a remoção de órgãos, tecidos e partes do corpo humano para fins de transplante e tratamento". Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF), 23 mar 2001: Seção 1: 1; [acesso em 2020 Jul 06]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/LEIS_2001/L10211.htm

9. Lei n°9.175, de 18 de outubro de 2017 (BR). Regulamenta a Lei nº 9.434, de 4 de fevereiro de 1997, para tratar da disposição de órgãos, tecidos, células e partes do corpo humano para fins de transplante e tratamento. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF), 18 out 2017: Seção 1: 1; [acesso em 2021 Mar 02]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/decreto/D9175.htm

10. Paggiaro AO, Cathalá BS, Isaac C, Carvalho VF, Oliveira R, Gemperli R. Perfil epidemiológico do doador de pele do Banco de Tecidos do Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2017;16(1):23-7.

11. Associação Brasileira de Transplante de Órgãos (ABTO). Registro Brasileiro de Transplantes (RBT). Dimensionamento dos transplantes no Brasil e em cada estado (2012-2019) [Internet]. São Paulo: ABTO; 2019; [acesso em 2020 Jul 06]. Disponível em: https://site.abto.org.br/publicacao/rbt-2019/

12. Matioski AR, Silva CRGBP, Cunha DRS, Calomeno LHA, Herson MR, Bonato FT, et al. First-year experience of a new skin bank in Brazil. Plast Aesthetic Res. 2015;2(6):6-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4103/2347-9264.169496

13. Silveira DPM, Rech DL, Pretto Neto AS, Martins ALM, Ely PB, Chem EM. Banco de pele de Porto Alegre: produtividade e perfil dos doadores. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(3):6.

14. Lindford AJ, Frey I, Vuola J, Koljonen V. Evolving practice of the Helsinki Skin Bank. Int Wound J. 2010 Ago;7(4):277-81.

1. Faculty Evangélica Mackenzie do Paraná,

Medicine, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

2. Hospital Universitário Evangélico Mackenzie,

Service of Plastic Surgery and Burns, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

GLAL Analysis and/or data interpretation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

RD Analysis and/or data interpretation, Final manuscript approval, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing

MCS Conception and design study, Final manuscript approval, Investigation, Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing

MT Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing

RFBN Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing Methodology

Corresponding author: Giovana Landal de Almeida Lobo Rua Padre Anchieta, 1846, Conjunto 103, Curitiba, PR, Brazil. Zip Code: 80730-000 E-mail: giovana.landau@gmail.com

Article received: May 08, 2020.

Article accepted: January 10, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter