Original Article - Year 2021 - Volume 36 -

Simple and composite circumferential abdominoplasty: technical evolution, 10-year experience and analysis of complications

Abdominoplastia circunferencial simples e composta: evolução técnica, experiência de 10 anos e análise das complicações

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery after massive weight loss evolve with large skin folds in various body regions, including the abdomen. In patients with dermofat excesses throughout the abdominal circumference and ptosis of the gluteal region, circumferential abdominoplasty (simple or composite) has been an effective surgical solution conventional or "anchor" abdominoplasty brings unsatisfactory results in those patients with severe dysmorphia. The objective is to analyze the technical evolution of simple and composite circumferential abdominoplasty and its complications.

Methods: Twenty-nine patients were evaluated, 28 females, with a mean age of 41.17 years, submitted to circumferential abdominoplasty between 2002 and 2012. This retrospective study, conducted through data collected from medical records, evaluated: surgery time, the weight of the resected surgical specimen, length of hospital stays, antibiotic therapy used, associated complications, and changes in the surgical technique in this period.

Results: Composite circumferential abdominoplasty was performed in 23 patients (79.3%) and the simple one in six (20.7%). The mean surgical time was 346 minutes, and the surgical specimen's mean weight was 4323 grams. Three patients (10.3%) had significant complications (symptomatic anemia and major suture dehiscence) and five (17.2%) minor complications (minor dehiscence, slight spontaneous bleeding, seroma, and hypertrophic scarring). Between 2002 and 2004, 75% of the complications occurred. The reoperation rate was 6.9%.

Conclusion: There was a significant technical evolution in circumferential abdominoplasty performance, and the incidence of complications and the rate of reoperation were similar to those found in the literature.

Keywords: Abdominoplasty; Adverse effects; Skinfolds; Obesity; Morbid obesity; Body contour; Postoperative complications; Quality of life.

RESUMO

Introdução: Pacientes portadores de obesidade mórbida submetidos à cirurgia bariátrica, após perda ponderal maciça, evoluem com grandes dobras de pele em várias regiões do corpo, incluindo abdome. Nos pacientes com excessos dermogordurosos em toda circunferência abdominal e ptose da região glútea, a abdominoplastia circunferencial (simples ou composta) tem demonstrado ser uma solução cirúrgica eficaz, pois a abdominoplastia convencional ou "em âncora" traz resultados insatisfatórios naqueles pacientes com dismorfia severa. O objetivo é analisara evolução técnica da abdominoplastia circunferencial simples e composta e suas complicações.

Métodos: Foram avaliados 29 pacientes, sendo 28 do sexo feminino, com média etária de 41,17 anos, submetidos à abdominoplastia circunferencial, entre 2002 e 2012. Este estudo retrospectivo, realizado através de dados colhidos dos prontuários médicos, avaliou: tempo de cirurgia, peso da peça cirúrgica ressecada, tempo de internação hospitalar, antibioticoterapia utilizada, complicações associadas e alterações ocorridas na técnica operatória neste período.

Resultados: A abdominoplastia circunferencial composta foi realizada em 23 pacientes (79,3%) e a simples em seis (20,7%). O tempo cirúrgico médio foi de 346 minutos e o peso médio da peça operatória foi 4323 gramas. Três pacientes (10,3%) tiveram complicações maiores (anemia sintomática e deiscência de sutura maior) e cinco (17,2%) complicações menores (pequenas deiscências, pequeno sangramento espontâneo, seroma e cicatriz hipertrófica). Entre 2002 e 2004 ocorreram 75% das complicações. O índice de reoperação foi de 6,9%.

Conclusão: Houve importante evolução técnica na realização da abdominoplastia circunferencial, sendo que a incidência de complicações e a taxa de reoperação foram similares àquelas encontradas na literatura.

Palavras-chave: Abdominoplastia; Efeitos adversos; Pregas cutâneas; Obesidade; Obesidade mórbida; Contorno corporal; Complicações pós-operatórias; Qualidade de vida

INTRODUCTION

After treatment of morbid obesity, the patient evolves with great weight loss, consequently decreased thickness of adipose tissue (hypodermis), skin sagging, and extensive skin folds distributed in various areas of the body 1. The superficialis fascia, distended while the patient was obese, now presents loose2. The post-bariatric patient’s skin has lower retraction capacity and decreased elasticity, mainly provided by the lower density of collagen fibers in dermal matrix3 or higher proportion of fine fibers than thick fibers4. This complex condition is defined as body dysmorphia, and, in these circumstances, we identified patients with a small amount of subcutaneous adipose tissue and significant excess skin (Figure 1).

Plastic surgery aims to dry out skin excesses, provide more harmonic body contouring, and minimize the side disorders that accompany dysmorphia, and often the first surgery requested is abdominoplasty5.

The most frequent abdominoplasty techniques are those performed with cross-sectional (classical), vertical, or anchor incision (“fleur-de-lis”). Classical abdominoplasty6,7, when applied to a patient with considerable dermofat remains, leaves lateral cutaneous remnants, which are treated with the extension of the incisions to the flanks, defining what is known as flanctoplasty8.

As a natural sequence of flankplasty, to improve the contour of the entire circumference of the abdomen and suspend the gluteal region, the incisions are extended until the projection of the spine, constituting circumferential abdominoplasty (CA)9-11, belt lipectomy12,13 or simple circumferential abdominoplasty (SCA)14. When these patients also present with dermo fat accumulations in the epigastrium and supra or periumbilical region, fusiform vertical excision associated with the transverse incision is indicated, constituting the composite circumferential abdominoplasty (CCA), resembling an anchor14.

OBJECTIVES

This study aims to analyze the technical evolution of simple and composite circumferential abdominoplasty and its complications.

METHODS

For the present retrospective study, 29 patients were selected, through medical records, enrolled and followed up at the Plastic Surgery Outpatient Clinic of the Division of Plastic Surgery and Burns of the Hospital das Clínicas of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo, who had undergone circumferential abdominoplasty, between 2002 and 2012.

Inclusion criteria of the patients: age between 18 and 65 years, at the time of the CA; surgery performed between June 1, 2002, and December 31, 2012; and body weight stability for a minimum period of 12 months.

Exclusion criteria: weight loss through clinical treatment; weight loss through another bariatric surgery technique different from that described by Capella-Fobi; and association of another surgery with CA.

The research project was presented to CAPPesq - Ethics Committee for The Analysis of Research Projects of the Hospital das Clínicas of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo, under registration number 11,819, and approved without restrictions. The project was also registered and approved at the Brazil Platform of the National Research Ethics Commission (CONEP) of the Ministry of Health, under Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Appreciation (CAAE) number 26869314.7.0000.0068.

Data were collected from patients such as name, age, date of surgery, height, body weight, body mass index (BMI) pre-gastroplasty, and plastic pre-surgery. The following items were also analyzed: surgery time, the weight of the resected surgical specimen, hospital stay time, antibiotic therapy used, and associated complications.

Patients were divided into two groups: A (patients operated between 2002 and 2004) and B (operated between 2005 and 2012). Changes in surgical demarcation and technical evolution (learning curve) occurred between the groups.

The complications were divided into major and minor, considering that, for the treatment of the larger ones, surgical intervention, increase in the hospitalization period, or rehospitalization15,16 (Chart 1) was required.

| Larger | Smaller |

|---|---|

| Great dehiscence | Seroma |

| Bruise | Small dehiscence |

| Symptomatic anemia | Minor bleeding |

| Flap necrosis | Hypertrophic scar |

| Infection/abscess | Asymptomatic anemia |

| Deep vein thrombosis | Infection/cellulite |

| Pulmonary embolism | Pulmonary atelectasis |

| Greasy embolism | |

| Death |

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 29 patients, 28 women (96.5%) and one man (3.5%). The mean age of the sample was 41.17 years (26-71 years).

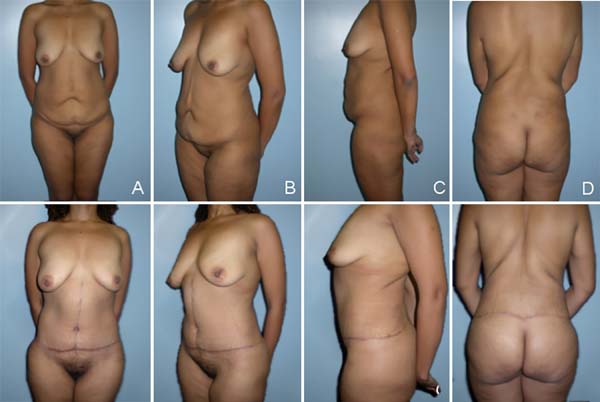

SCA was performed in six patients (20.7%), while CCA was performed in 23 patients (79.3%) (Figures 2 and 3).

The mean height of the patients was 1.62m, with extremes between 1.49m and 1.78m. Before gastroplasty, the average body weight was 145.6kg (105-234kg); and BMI before gastroplasty was 55.41kg/m2 (39.0-82.9kg/m2). The average weight before plastic surgery was 77.62kg (51-98kg; and the mean BMI before plastic surgery was 29.56kg/m2 (19.2-37.5kg/m2).

The mean surgical time to perform THE and CCA was 346 minutes, i.e., 5h46min, ranging from 250 to 480 minutes. The mean length of hospital stay was 4.34 days (2-15 days). The mean weight of the resected surgical specimen was 4323 g (3100-6356 g).

Antibiotic therapy with a first-generation cephalosporin, cephalothin, or cefazolin was used for all patients. They received the first dose 30 minutes before surgery, and the therapeutic regimen was maintained for seven days.

Three patients (10.3%) had major complications. Two patients (6.9%) presented symptomatic anemia and required a blood transfusion because they presented postural hypotension; one patient received six units of red blood can concentrates and the other one unit. One patient (3.4%) presented suture dehiscence, which required hospital readmission, debridement, and resuture in the operating room.

Five patients (17.2%) presented minor complications. Two patients (6.9%) had small dehiscences, which were treated with serial dressings. One patient (3.4%) had minor spontaneous bleeding, without the need for surgical intervention; one patient (3.4%) required serial punctures of seroma on an outpatient basis, and one patient (3.4%) evolved with hypertrophic scarring in the infraumbilical region (Table 1).

| Complications | Patients (n=29) |

|---|---|

| Larger | |

| Great dehiscence | 1 (3.4%) |

| Bruise | - |

| Symptomatic anemia | 2 (6.9%) |

| Flap necrosis | - |

| Infection/abscess | - |

| Deep vein thrombosis | - |

| Pulmonary embolism | - |

| Greasy embolism | - |

| Death | - |

| Smaller | |

| Seroma | 1 (3.4%) |

| Small dehiscence | 2 (6.9%) |

| Minor bleeding | 1 (3.4%) |

| Hypertrophic scar | 1 (3.4%) |

| Asymptomatic anemia | - |

| Infection / cellulite | - |

| Pulmonary atelectasis | - |

Between 2002 and 2004 (group A), there were six complications, two major and four minor complications, corresponding to 75% of the total complications. Between 2005 and 2012 (group B), there were two complications (25%), with a major complication and a minor complication.

The statistical analysis, performed through the Fisher’s test, showed no significant difference between the two time periods regarding the occurrence of complications (p=0.215), according to Table 2.

| The | B | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With complication | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| 40.0% | 14.3% | 27.6% | |

| No complication | 9 | 12 | 21 |

| 60.0% | 85.7% | 72.4% | |

| Total | 15 | 14 | 29 |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| p=0.215 |

The extent of Fisher’s test also showed no statistically significant difference between the complications that occurred between the two time periods, when divided into larger and smaller ones(p=0.444), according to Table 3.

| The | B | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With major complication | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 13.3% | 7.1% | 10.3% | |

| With minor complication | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 26.7% | 7.1% | 17.2% | |

| No complication | 9 | 12 | 21 |

| 60.0% | 85.7% | 72.4% | |

| Total | 15 | 14 | 29 |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| p=0.444 |

Of the 29 patients, two (6.9%) have been reoperated. One patient (3.4%) was submitted to readmission for debridement and new wound suture, and the other (3.4%) was subsequently submitted to hypertrophic scar resection to refine the result.

DISCUSSION

Circumferential abdominoplasty is a technique widely used for patients with high weight loss and who have excessive dermofat in the anterior, lateral and posterior abdomen. Besides, the gluteal region ptosis, requiring or not to increase the buttocks’ volume, is also a primary factor in the technique’s indication. It should also be quantified the excess of skin and adipose tissue in the epigastric region and the presence or not of the scar from gastroplasty by conventional means, as these will be determining factors for the indication of simple or composite circumferential abdominoplasty17.

The satisfaction of these patients is directly related to the body extension treated; that is, the larger the area with body contour restored, the greater its satisfaction. For this reason, circumferential abdominoplasty, which treats the entire circumference of the abdomen and suspends the lateral face of the thighs and the gluteal region, generally promotes great satisfaction to patients18,19.

Several authors have described their techniques, associating them with liposuction and making surgical demarcation changes, always to position the posterior scar7,8,10-14 properly. It is essential to highlight that the body contour surgery group of the plastic surgery division and burns of HCFMUSP followed and contributed substantially in this historical context.

In the first operated cases - group A - the posterior scar was positioned more superiorly in the dorsal region. This promoted the trunk’s waistlines, but it became difficult to cover the scar with the bathing suits. At this time, there was partial dehiscence of the posterior scar on the coccyx in some patients, caused by excessive tension on the scar because the posterior incisions were parallel. Since then, the distance between the posterior demarcation lines in the area over the coccyx has been decreased. Thus, this intercurrence became infrequent (Figure 4).

The moment of change of decubitus of the anesthetized patient is critical and should be carefully planned concerning monitoring, venous access, airway, and the patient’s own physical state. These decubitus changes should be avoided in hypotensive or hypohydrated patients, at risk of triggering deleterious autonomic reflexes by altering body fluids’ position with severity20. For this reason, it opts for the beginning of surgery with the patient in horizontal ventral decubitus and, after synthesis of the posterior region, it is changed to prone dorsal decubitus. With this, there is only one change of decubitus in the transoperative period.

Another crucial technical evolution between the groups was the proscription of drains’ use and the beginning of the points of apathy or progressive tension. The use of drains is an exception. With the fixation of flaps to aponeurosis in both anterior and posterior regions, there is a considerable reduction or elimination of dead spaces21-24.

Three patients (10.3%) presented major complications - symptomatic anemia (n=2) and suture dehiscence that required debridement and resuture (n=1), an incidence compatible with the literature. There was no deep vein thrombosis in this series, pulmonary or fatty embolism, systemic infection, or hematoma requiring surgical intervention. Five patients (17.2%) presented minor complications (small dehiscence or bleeding, seroma, and hypertrophic scar), incidence also compatible with that found in the literature15,25-27.

The incidence of complications was higher in group A (75%) when compared to group B (25%). This suggests the positive influence of the learning curve and the surgical team’s interaction regarding pre, trans and postoperative care, although there is no statistically significant difference (Tables 2 and 3).

The reoperation rate was 6.9% (n=2), also compatible with the literature, and one patient was operated on for debridement and resuture of the surgical wound, and the other patient was operated on later to improve the hypertrophic scar25,26.

It is known that Latino patients are concerned with the extent and positioning of scars. Perhaps, for this reason, CA is not as widespread in Latin America as in North America. There were changes in surgical demarcation, and the surgical team’s training decreased the operative time and minimized risks. Even so, it continues to be considered a major surgery28,29.

CONCLUSION

An essential technical evolution has occurred in the performance of circumferential abdominoplasties, such as better positioning of incisions, sutures, and restriction in the indication of the use of drains. In the sample presented, the incidence of complications and reoperation rates were similar to those found in the literature.

REFERENCES

1. Vandeweyer E, Van Geertruyden J, Fontaine S, Duchateau J, Houben JJ, Goldschimidt D. La chirurgie plastique post-gastroplastie. Rev Méd Brux 1996;17:244- 7.

2. Lockwood TE. Superficial fascial system (SFS) of the trunk and extremities: a new concept. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991 Jun;87(6):1009-18.

3. Opheu SC, Coltro PS, Scopel GP, Gomez DS, Rodrigues CJ, Modolin MLA, et al. Collagen and elastic content of abdominal skin after surgical weight loss. Obes Surg. 2010 Abr;20(4):480-6.

4. Rocha RI. Avaliação histomorfométrica da pele da região abdominal de pacientes com obesidade mórbida antes e após perda acentuada de peso pós-cirurgia bariátrica [tese]. São Paulo (SP): Faculdade de Medicina - Universidade de São Paulo (USP); 2016.

5. Favre S, Egloff EV. Body contouring surgery after massive weight loss. Rev Med Suisse. 2005 Jul;1(28):1863-7.

6. Callia W. Contribuição para o estudo da correção cirúrgica do abdome pêndulo e globoso (técnica original) [tese]. São Paulo (SP): Faculdade de Medicina - Universidade de São Paulo (USP); 1965.

7. Pitanguy I. Abdominal lipectomy: an approach to it through analysis of 300 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40(4):384-91.

8. Baroudi R. Flankplasty: a specific treatment to improve body contouring. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;27(5):404-20.

9. Carwell GR, Horton CE. Cirumferencial torsoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38(3):213-6.

10. Pascal JF, Le Louarn C. Remodeling bodylift with high lateral tension. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002 Jun;26(3):223-30.

11. Modolin M, Cintra Junior W, Gobbi CIC, Ferreira MC. Circumferential abdominoplasty for sequential treatment after morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2003 Fev;13(1):95-100.

12. Aly AS, Cram AE, Chao M, Pang J, McKeon M. Belt lipectomy for circumferential truncal excess: the University of Iowa experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003 Jan;111(1):398-413.

13. Hurwitz DJ. Single-staged total body lift after massive weight loss. Ann Plast Surg. 2004 Mai;52(5):435-41;discussion:441.

14. Cintra W, Modolin M, Gobbi CIC, Gemperli R, Ferreira MC. Abdominoplastia circunferencial em pacientes após cirurgia bariátrica: avaliação da qualidade de vida pelo critério adaptativo. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(1):52-6.

15. Neaman KC, Hansen JE. Analysis of complications from abdominoplasty: a review of 206 cases at a university hospital. Ann Plast Surg. 2007 Mar;58(3):292-9.

16. Smaniotto PHS, Saito FL, Fortes F, Scopel SO, Gemperli R, Ferreira MC. Comparative analysis of the evolution and postoperative complications of body contouring plastic surgeries after massive weight loss in young and elderly patients. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012 Set;27(3):441-4.

17. http://www.teses.usp.br/index.php?option=com_jumi&fileid=11&Itemid=76&lang=pt- br&filtro=Cintra%20junior

18. Cintra Junior W, Modolin M, Gemperli R, Gobbi CIC, Faintuch J, Ferreira, MC. Quality of life after abdominoplasty in women after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2008;18(6):728- 32.

19. Hammond DC, Chandler AR, Baca ME, Ly YK, Lynn JV. Abdominoplasty in the overweight and obese population: outcomes and patient satisfaction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Out;144(4):847-53.

20. Lacerda MA. Anestesia para cirurgia plástica no ex-obeso mórbido. In: Resende JHC, ed. Tratado de cirurgia plástica na obesidade. Rio de Janeiro: Rubio; 2008. p. 183-93.

21. Pollock H, Pollock T. Progressive tension sutures: a technique to reduce local complications in abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000 Jun;105(7):2583-6;discussion:2587-8.

22. Boggio RF, Almeida FR, Baroudi R. Adhesion suture in plastic of body contouring. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2011;26(1):121-6.

23. Kosins AM, Scholz T, Cetinkaya M, Evans GRD. Evidence-based value of subcutaneous surgical wound drainage: the largest systematic review and meta- analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Ago;132(2):443-50.

24. Pollock TA. Commentary on: reduced seroma risk in drainless abdominoplasty using running barbed sutures: a 10-year multicenter retrospective analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2020 Abr;40(5):538-40.

25. Rohrich RJ, Gosman AA, Conrad MH, Coleman J. Simplifying circumferential body contouring: the central body lift evolution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Ago;118(2):525-3;discussion:536-8.

26. Dini M, Mori A, Cassi LC, Lo Russo G, Lucchese M. Circumferential abdominoplasty. Obes Surg. 2008;18(11):1392-9.

27. Nemerofsky RB, Oliak DA, Capella JF. Body lift: an account of the 200 consecutive cases in the massive weight loss patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Fev;117(2):414-30.

28. Cintra Junior W. Abdominoplastia circunferencial simples e composta: evolução técnica, experiência de 10 anos e análise das complicações [tese]. São Paulo (SP): Faculdade de Medicina - Universidade de São Paulo (USP); 2014.

29. Small KH, Constantine R, Eaves FF, Kenkel JM. Lessons learned after 15 years of circumferential bodylift surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2016 Jun;36(6):681-92.

1. Hospital das Clínicas, Faculty of Medicine,

University of São Paulo, Division of Plastic Surgery, São Paulo, SP,

Brazil.

Institution: Hospital das Clínicas, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, Division of Plastic Surgery, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

WC Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Supervision, Validation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

MM Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing

RIR Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing

Corresponding author: Wilson Cintra Avenida São Gabriel, 201, Conjunto 704/5, Jardim Paulista, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 01435-001 E-mail: wcintra@terra.com.br

Article received: April 05, 2020.

Article accepted: January 10, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter