Case Report - Year 2020 - Volume 35 - Issue 4

Bernard-Burow flap unilateral with cheek mucosa "cutback" for treatment of lower lip tumor: a case report

Retalho de Bernard-Burow unilateral com "cutback" de mucosa jugal para tratamento de tumor de lábio inferior: relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Lip cancer corresponds to 25-30% of all oral cancers, with the lower lip being more frequent. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common subtype, with smoking as one of the main risk factors. The report demonstrates a simple and effective technique for SCC's surgical treatment on a smoking patient's lower lip. Even in a defect larger than 50% of the initial lip diameter, the unilateral Bernard-Burow flap proved feasible. The addition of "cutback" in the mucosa and parsimonious dissection by planes may have provided a good aesthetic and functional evolution since it determined tension relief on the sutures. The less complex execution of this reconstruction, compared to other techniques, can guarantee a good alternative to decrease postoperative morbidity in this type of surgery.

Keywords: Face; Lip neoplasms; Squamous cell carcinoma; Smoking; Plastic surgery; Reconstructive surgical procedures

RESUMO

O câncer de lábio corresponde a 25-30% de todos os cânceres de boca, sendo mais frequente o de lábio inferior. O carcinoma de células escamosas (CCE) é o subtipo mais incidente, estando o tabagismo como um dos principais fatores de risco. O relato demonstra técnica simples e efetiva para tratamento cirúrgico de CCE no lábio inferior de paciente tabagista. A realização de retalho unilateral de Bernard-Burow, mesmo em defeito maior que 50% do diâmetro inicial do lábio, mostrou-se factível. A adição de "cutback" na mucosa e dissecção parcimoniosa por planos pode ter propiciado uma boa evolução estética e funcional, já que determinou alívio na tensão sobre as suturas. A menor complexidade de execução desta reconstrução, se comparada a outras técnicas, pode garantir uma boa alternativa na tentativa de diminuir a morbidade pós-operatória neste tipo de cirurgia.

Palavras-chave: Face; Neoplasias labiais; Carcinoma de células escamosas; Tabagismo; Cirurgia plástica; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos

INTRODUCTION

Lip cancers are the most frequent malignant neoplasms to affect oral cavity1. Up to 90% of cases involve the lower lip, with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) being the most prevalent histological type2. In contrast, when affected, the upper lip has basal cell carcinoma (BCC) as the most frequent histological type. Among the most related etiological factors are smoking, exposure to ultraviolet radiation, and arsenic. Chronic actinic cheilitis is the precursor lesion of SCC3.

After removing these lesions, the lip reconstruction is problematic due to the presence of mobile structures that need different mechanical and aesthetic functioning, both static and in motion4. Although defects smaller than 30% of the lower lip’s size can be repaired primarily, the need for appropriate surgical margins in the case of malignant lesions usually leads to performing flaps. The final defect size is generally larger than one third or, in extreme cases, two-thirds of the dimensions of the original lip5. This report seeks to show a simplified solution, with good clinical evolution and a low rate of sequelae for removing an extensive amount of lower lip in a patient with SCC and high smoking burden.

CASE REPORT

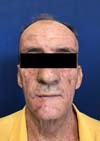

Male patient, from rural Minas Gerais, with a lower lip tumor, was seen at the plastic surgery outpatient clinic of Hospital das Clínicas, Federal University of Minas Gerais. He reports that the lesion started as a friable and painful whitish plaque, and its growth was neglected for two years. He sought care due to the appearance of angular stomatitis and constant bleeding from the injury, which prevented him from smoking (Figure 1). A 42 year-smoker (straw cigarette and pipe). Moderate drinker of barley derivatives and distillates. No other comorbidities were diagnosed at the time of the consultation. He denied the use of any medications or illicit drugs. He denied known allergies. User of upper and lower dental prostheses.

The patient presented ectropion on the left, multifocal actinic keratosis, and cryotherapy scars, secondary to surgery to remove skin tumors on clinical examination. He had no palpable cervical lymph node enlargement, nor signs or symptoms in other systems.

He presented a hyperdense lesion on the lower lip on tomographic examination, occupying 39% of its extension, without bone infiltration. He had no cervical or occipital lymph node enlargement on examination.

He underwent excision of the lesion in a hospital environment, under a day hospital regime. For reconstruction, the lesion with radial margins of 1 cm was marked with a dermographic pen, in addition to the Bernard-Burow flap bilaterally (Figure 2).

The procedure was performed under continuous monitoring, with infiltration of adrenalized anesthetic solution 1: 80,000 (0.5% bupivacaine 20ml + 2% lidocaine 20ml + 40ml saline) locally, in addition to bilateral mental and infraorbital nerves block.

The incision (in the full plane) started at the marked margin, passing through the right buccal rhyme, preserving the modiolus, and bordering the mentonian subunit. The final defect occupied approximately 60% of the lower lip’s total length (Figure 3).

Surgical materials were changed to safeguard the oncosurgical principles. A mucosal incision was made on the buccal surface, from the first lower right molar to the first lower left molar (46-36), with a cranial and oblique jugal extension towards the right upper second molar. A subperiosteal detachment was performed from the gingivolabial flap to the gnathium region, preserving the mental bundles (Figure 4).

Previously, the right nasogenian and mentonian triangles were excised, with parsimonious detachment from the supra-SMAS plane (superficial muscle-aponeurotic system), in addition to advancing the cheek mucosa to release the modiolus region to facilitate lip closure.

After confirmation of the defect’s tension-free closure, sutures of the gingivolabial mucosa and flaps of the posterior labial layer were made successively with 4-0 polyglactin threads (single stitches). The muscle layer was sutured with “x” stitches, also with 4-0 polyglactin. The dermal suture was made by advancing the anterior flaps, with the skin sutured with 5-0 nylon threads and the lip with 5-0 polyglactin, in simple stitches.

The procedure lasted seventy minutes, and the piece was sent for anatomopathological examination, which showed well-differentiated, invasive, and ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma with free margins.

Mouthwashes with cetylpyridinium were advised every 12 hours postoperatively, in addition to analgesic prescription.

The patient returned to remove the stitches in seven days, showing preserved speech and food, oral continence, symmetrical mimicry, and the possibility of withdrawing his prostheses for hygiene without impairing healing (Figure 5).

He maintained a good evolution on the 50th postoperative day when he returned to receive the anatomopathological report (Figures 6 and 7). He continued using antimycotics and local corticotherapy to treat angular stomatitis.

DISCUSSION

The patient had several risk factors consistent with what was reported in the literature3, including aggravating factors for surgical healing, such as smoking, which was not interrupted, even after due guidance.

The primary objectives of lip reconstruction (preservation of function, muscle reconstruction, and oral sphincter competence, closing in three planes, and accurate alignment of the vermilion)3-5 were achieved through a simple and easy reproduction technique, with good final aesthetic result.

Other options available for the case, such as the Karapandzic or Fujimori flap, have a greater degree of complexity4,6 and were left as a rescue alternative in case of recurrence or insufficient excision of margins.

The reconstruction must include the cutaneous, muscular, and mucous plane in the inferior vestibular sulcus’ depth. Much emphasis exists on the solution for skin closure and, whenever possible, with closure with innervated (functional) muscle 4,7. However, there are few reports of treatment of the mucous plane in the vestibular region and posterior wall of the lower lip. One of the efficient and straightforward maneuvers for reconstructing this anatomical portion is the mucoperiosteal detachment with posterior relieving incisions (“cutback”) to allow the advancement of all structures in the direction of lip closure in all layers. This reduces the tension in the muscular and skin closure and maintains the vestibular depth, and orienting the leftover mucosa towards the vermilion, using it if necessary.

Performing the “cutback” on the cheek mucosa relieved the tension under the mucosal suture, which was generally friable and exposed to dehiscence. Associated with dissection by layers (different from the one initially proposed by Bernard and Burow)8, may have positively influenced the evolution postoperative, culminating in a good oncological, functional, and aesthetic result, in addition to ensuring an adequate level of patient satisfaction.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that the technical suggestion presented can help other surgeons resolve difficult closure cases, providing the reserve of more complex flaps for defects that exceed two-thirds of the lip’s size. On the other hand, it formalizes an accurate description of the mucosal plane’s treatment, neglected in the current literature.

REFERENCES

1. Ozdogan F, Ozcan M, Selcuk A, Dere H. Bernard-Von Burrow flap and unilateral Webster modification for reconstruction of upper lip. J Clin Anal Med. 2017;8(Suppl 1):14-6.

2. Mahmoud WH. Surgical outcome of lower lip reconstruction using the Webster flap. Merit Res J Med Med Sci. 2016;4(8):399-405.

3. Goldman A, Wollina U, França K, Lotti T, Tchernev G. Lip repair after mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma by bilateral tissue expanding vermillion myocutaneous flap (Goldstein technique modified by Sawada). Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018 Jan;6(1):93-5.

4. Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CE, Buzzo CL, Raposo-Amaral CA. Functional lower lip reconstruction with the modified Bernard-Webster flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015 Nov;68(11):1522-8.

5. Ebrahimi A, Motamedi MHK, Ebrahimi A, Kazemi M, Shams A, Hashemzadeh H. Lip reconstruction after tumor ablation. World J Plast Surg. 2016 Jan;5(1):15-25.

6. Kerawala C, Roques T, Jeannon JP, Bisase B. Oral cavity and lip cancer: United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016 May;130(Supl 2):S83-S9.

7. Sane VD, Rathi P, Narla B, Khandelwal S, Pathan W. Karapandzic flap: a useful option for reconstruction of lower lip. J Craniofac Surg. 2018 Dec;30(1):e32-e4.

8. Neligan PC, Gottlieb LJ. Lip reconstruction. 12. In: Neligan PC, Gottlieb LJ, eds. Plastic surgery. 4a ed. London: Elsevier; 2018. v. 3. p. 306-28

1. Hospital das Clínicas, Federal University of the Minas Gerais, Plastic Surgery

Service, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

Institution: Hospital das Clínicas, Federal University of the Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

SASRF Conception and design study, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation

MMC Realization of operations and/or trials

TES Realization of operations and/or trials

GMCS Realization of operations and/or trials, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing

Corresponding author: Sergio Antonio Saldanha Rodrigues Filho, Avenida Professor Alfredo Balena, 110, 7º andar, Centro, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Zip Code: 30130-100. E-mail: drsergiorodrigues@gmail.com

Article received: January 07, 2019.

Article accepted: July 15, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter