Review Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

COVID-19: how to proceed with the practice of plastic surgery in Brazil. What do we know right now?

COVID-19: como proceder na prática da cirurgia plástica no Brasil. O que sabemos até agora?

ABSTRACT

COVID-19 (coronavirus disease, described in 2019) is an infectious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Most confirmed cases are mild or asymptomatic, but the most severe cases can progress to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and death. In Brazil, there is a scenario of an exponential increase in cases, making it challenging to identify the source of contagion. We cannot yet specify when the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak will occur in our country or when the numbers of new contaminants and deaths will begin to decrease. So, the most important thing is protection against a virus for which all the details about contagion, transmission, and treatment are not known. The pandemic impacted and modified medical care, especially for surgical specialties, where face-to-face care is essential and cannot be replaced entirely by telemedicine. Thus, this review aimed to compile theoretical and practical aspects regarding the pandemic COVID-19 and its impact on plastic surgery activity routine. Protocols are proposed for resuming our routines, analyzing countries' experience at an advanced stage of the pandemic.

Keywords: Coronavirus infections; Surgery, Plastic; Patient safety; Elective surgical procedures; Protective devices; Pandemics.

RESUMO

COVID-19 (coronavirus disease, descrito em 2019) é uma doença infecciosa causada pelo coronavírus da síndrome respiratória aguda grave 2 (SARS-CoV-2). A maioria dos casos confirmados é leve ou assintomático, mas os casos mais graves podem evoluir para pneumonia grave com insuficiência respiratória e morte. Atualmente ocorre, no Brasil, um cenário de aumento exponencial de casos, dificultando a identificação da fonte de contágio. Ainda não podemos precisar quando ocorrerá o pico do surto de COVID-19 em nosso país ou quando os números de novos contaminados e óbitos começarão a diminuir. Nesse momento, o mais importante é a proteção contra um vírus do qual não se conhece todos os detalhes sobre contágio, transmissão e tratamento. A pandemia impactou e modificou a assistência médica, principalmente das especialidades cirúrgicas, onde o atendimento presencial é fundamental e não pode ser substituído integralmente pela telemedicina. Assim, o objetivo desta revisão foi compilar aspectos teóricos e práticos referentes à pandemia COVID-19 e seu impacto na rotina da atividade da cirurgia plástica. São propostos protocolos para retomada de nossas rotinas, analisando a experiência de países em fase mais adiantada da pandemia.

Palavras-chave: Infecções por coronavírus; Cirurgia plástica; Segurança do paciente; Procedimentos cirúrgicos eletivos; Equipamentos de proteção; Pandemias

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 (coronavirus diseases - 2019) is an infectious disease caused by the coronavirus of severe acute respiratory syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2)1. The most common symptoms are fever, cough and difficulty breathing, loss of taste or smell. Approximately 80% of confirmed cases are oligo/asymptomatic and most recover without sequelae2. However, 15% of infections are severe, with extensive viral pneumonia cases, of which 40% progress to SARS, many of them requiring assisted ventilation in intensive care units, and 20% evolve to death. In the most severe cases, associated with pneumonia, we observed disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiple organ failure3.

The disease is transmitted through droplets produced in the respiratory tract of infected people. When sneezing or coughing, these droplets can be inhaled or directly reach the mouth, nose, or eyes of close contact people. Alternatively, the hands can touch contaminated surfaces and carry the virus to the mucous membranes, infecting people. The time interval between exposure to the virus and the onset of symptoms is 2 to 14 days, with five days average. Among the risk factors for a worse prognosis are advanced age and comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity, and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. The diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms and risk factors and confirmed with real-time polymerase chain reaction assays to detect virus RNA in mucus or blood samples (RT-PCR). When the direct search for viral RNA is negative or cannot be made, the diagnosis can be confirmed by serology, or it can be presumptive, based on the clinical picture and characteristic chest computed tomography (CT) image.

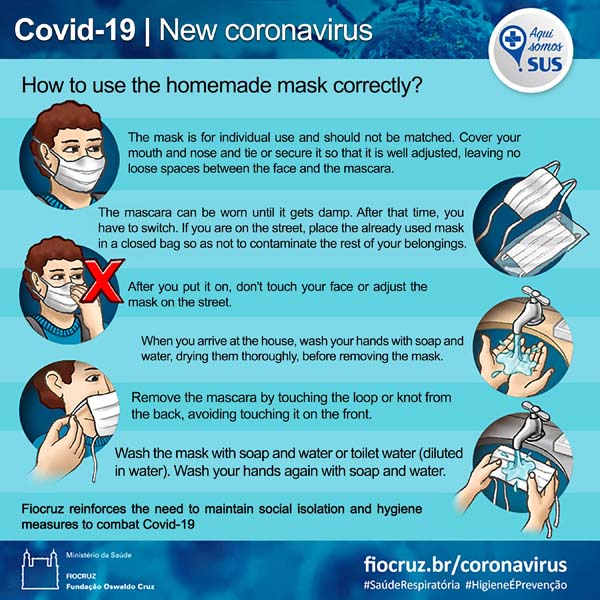

Prevention measures include frequent handwashing, avoiding close contact with other people, and avoiding touching the mucous membranes with your hands. The use of surgical masks was initially recommended only for people suspected of being infected or for the caregivers of infected people, and, currently, the recommendation is for the general public. There is no specific vaccine or antiviral treatment for the disease. We still do not have any medication with proven effectiveness in this first phase of the infection, known as the viral phase. The most distressing and frightening of the disease is not accurately predicting and preventing the progression to its phase II of pneumonia and phase III of SARS. In this phase, ventilatory support with oxygen therapy is essential, and the treatment of immune dysregulation and the coagulation system, which become more harmful than the cytopathic effect of the virus.

The pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus had its first cases identified in late 2019, starting in Wuhan, China. It spread across the world quickly and progressively, with an exponential increase in cases, making it challenging to identify the source of contagion. We cannot yet specify when the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in Brazil will occur or when the numbers of new contaminants and deaths will begin to decrease. There are still many doubts about the virus’s behavior, both on an epidemiological scale and on an individual physiological issue. We know which risk groups are most affected, but we also see patients outside those groups succumb to it. Due to the lack of proven treatments, social distance is a real measure, but its duration and magnitude are heated debate objects.

The pandemic impacted and modified medical care, especially for surgical specialties, where face-to-face care is essential and cannot be replaced entirely by telemedicine. But we have countries that have already gone through the disease’s peak and are resuming their economic activities, including attending clinics to elective patients. This study aims to analyze theoretical and practical aspects related to the pandemic COVID-19 and its impact on the routine of plastic surgery activity, evaluating the experience of countries in an advanced stage of the pandemic and also to propose protocols for resuming our routines.

METHODS

Research carried out in PubMed in 2020, with the following terms related to the virus: “COVID”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “Coronavirus,”; crossed with terms: “plastic surgery”, “elective surgery”, “surgical”. Websites of national and international agencies that disseminate epidemiological factors, guidelines, and guidance for COVID-19 were also researched.

RESULTS

Crossing the terms “COVID-19”, or “SARS-CoV-2” or “Coronavirus” with “plastic surgery”, “elective” and “surgical”, 15, 22 and 125 articles were identified, respectively, totaling 162 studies. Articles such as case reports, description of surgical techniques in infected patients, and medical education guidelines during a pandemic were excluded, resulting in 127 articles that were analyzed in more detail. The articles describe surgical routines adopted by different services in the different regions affected by the pandemic such as SubSahara4, United States5-16, Italy17-25, Singapore26-30, China3,11,31-53, Turkey54, England41,55,56, Brazil57, Spain55,58, Pakistan59, Argentina21, among others. Descriptions of routines adapted to the pandemic COVID-19 were found in different medical specialties, such as gynecology and obstetrics58, vascular surgery60, cardiac surgery61, bariatric surgery51,62,63, ophthalmology64,65, plastic surgery21,36,39,55,58,66-73 e oncologia24,25,32,67,74-84 and oncology 24,25,32,67,74-84.

A survey carried out by Al-Benna and Gohritz, in 202073, showed that 22% of the websites of national plastic surgery societies have a specific section on COVID-19, with guidelines for their members or the general population. Our society proudly dedicates a chapter and a series of videos and web meetings on the topic (www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br). In this analysis of the worldwide literature on guidelines, we unanimously observed the recommendation to test the presence of viruses (RT-PCR) or antibodies in patients (serology) in a comprehensive way 85, however, in our country, so far, we do not have government action in this regard, and we do not have enough tests available

Plastic surgery comprises a range of services of a peculiar nature, ranging from wounds, trauma, burns, reconstruction, oncology to cosmetic surgery, and cosmiatry. According to a survey by the American Society of Plastic Surgery, in 2018, around 6 million reconstructive procedures, 2 million aesthetic procedures, and 16 million minimally invasive cosmetic procedures were performed86. The pandemic does not affect the indication for emergency surgeries, but it does require well-established and rigorous adaptations of the hospital environment in terms of patient flow and personnel protection. The lower the circulation of people in any situation and, mainly, in hospital environments, the lower the risk of spreading the infection, and this premise directly affects elective surgeries, both essential and non-essential, and even more so any aesthetic procedure70.

The concept of elective surgery, in this pandemic moment, becomes even more conflicting and depends on the judgment of the surgeon and the patient, taking into account the risk/benefit ratio and biopsychosocial aspects, especially in reconstructive surgery. The Federal Council of Medicine (CFM), in an ordinance, defines only urgent and emergency surgery, and no specific definition of elective surgery was found. According to the report of the Regional Council of Medicine of the State of Acre, Brazil (CRM-AC), the surgeries are established as follows:

“ELECTIVE SURGERY: proposed surgical treatment, but the performance can wait for a favorable occasion, that is, it can be programmed.

URGENCY SURGERY: surgical treatment that requires prompt attention and must be performed within 24 to 48 hours.

EMERGENCY SURGERY: surgical treatment that requires immediate attention because it is a critical situation.”87

Stahel, in 202088, proposes an even more detailed classification of surgeries:

• Emergency: must be performed within 1 hour;

• Urgency: must be performed within 24 hours;

• Elective urgency: must be performed within two weeks;

• Essential elective: can be postponed for 1 to 3 months;

• Non-essential elective: can be postponed for> 3 months.

In plastic surgery, we consider elective oncology surgeries essential and, even so, there is a recommendation to individualize these procedures:

• Cutaneous oncology: Gentileschi et al., in 202067, define that only the cutaneous oncological cases below should be considered for surgery:

1. Reoperation of melanoma cases for margin expansion and excision of sentinel lymph node;

2. Skin tumors with bleeding and ulceration;

3. Patients being followed up for solid tumors where resection can increase survival (breast tumors and melanoma);

4. Aggressive fast-growing tumors (sarcoma and melanoma);

5. Basal cell carcinoma should be evaluated for location (eyelids, for example).

Breast reconstruction: Guidelines from the American Society of Breast Surgeons recommend that breast reconstructions be analyzed with caution. The procedure should be as less invasive as possible and, eventually, perform the definitive repair at the most appropriate time. Extensive procedures may require intensive care, which can increase the risk of contamination89.

There are reports in the literature of patients undergoing elective surgical procedures who, despite all negative screening for COVID-19, developed the disease in the postoperative severely, with death in most cases. The authors question the uncertainty of the NEGATIVE diagnosis before surgery and whether eventually, surgical trauma was not a factor in the worse prognosis of the disease. Besides, there was an exposure of all professionals and patients in the same environment at the time of surgery53,90,91. They recommend that elective surgeries be suspended. An increasing number of pieces of evidence show cardiorespiratory and microembolic or thrombotic complications in patients with the disease, but nothing is known about asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic patients63,90.

At the moment, the World Health Association and the official world bodies, recommend postponing elective surgeries85,92,93. The Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery also recommends postponing elective surgeries:

“Considering the very personal characteristic of the development of the disease in

each organism, which can range from asymptomatic to dramatically fatal evolution;

it remains clear that taking a patient to surgical treatment (other than urgency and/or

exceptionality as related to oncology), is to compete with recklessness and professional

insecurity, especially patient safety. The postoperative evolution of a patient, primarily

healthy, with COVID-19, can have dramatic consequences, which will certainly invoke

the surgeon’s responsibility.” (Report V - Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery [SBCP

in portuguese]).

And even referring to legal issues, the informed consent term must be increased by risks for COVID-19. However, also aware of these risks, the real danger to the patient during the perioperative period is not yet measurable.

When and how to resume elective surgery?

• Wait for favorable statistics to resume surgical activities: - Is the local number of confirmed cases decreasing?

• Are the local number of deaths and ICU admission falling?

• Informed consent, including information on signed COVID-19 (see the model in Annex 4).

Minimally invasive procedures39

• The closer the face, the higher the risk of contamination. Nasopharyngeal procedures, such as intranasal examination or dressings, are extremely contaminating.

• Aerosols of COVID-19 can remain in the air for up to 3 hours. The correct dispersion of aerosols consists of laminar flow from the environment, which is practically impossible in offices. Whenever possible, improve the ventilation of rooms.

Surgical procedures in a hospital setting

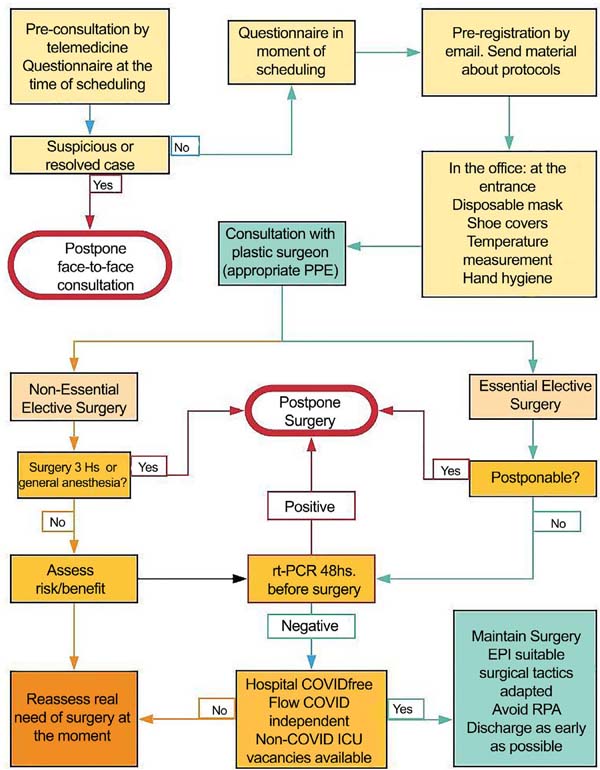

Health institution evaluation

• Respect the classification of the Hospital or Clinic for COVID-free or that there is a safe flow established for non-COVID-19 patients. Check the availability of COVID-free ICU beds.

• In general, hospitals have adapted to the routine change in the disinfection of rooms and equipment, since it is known that COVID 19 can remain on surfaces and in the air for a long time.

Patient selection for surgery

• Absence of changes to the questionnaire made in the scheduling (see questionnaire suggestion in Annex 2).

• Patient without comorbidities (low surgical risk).

• Elective surgery only after 1 or 2 months in patients who had COVID-19:

• Higher risk of thrombosis after the eighth day of symptom onset and up to 2 months after infection (data not scientifically confirmed). D-dimer levels, inflammatory cytokines, and liver enzymes are often altered during the disease, further compromising any surgical stress.

• Only admit patients with a negative RT-PCR test for COVID-19 48 hours before or positive IgG for elective surgeries. Remember that no test has 100% sensitivity. There is always the possibility of a false negative.

• Give preference to outpatient surgery and surgery lasting <3 hours.

• Prefer sedation or locoregional anesthesia, since there are reports of cases of activation of COVID-19 after orotracheal intubation in elective patients. In addition to a higher risk for the anesthesia team.

• There is a higher incidence of contaminated otolaryngologists than other specialties due to nasopharyngeal manipulation.

Surgical tactics and team protection

• Every patient with negative tests should be considered a potential COVID-19 vector.

• Protective equipment suitable for the whole team.

• Special care must be taken in surgeries that generate aerosols, such as laparoscopies and electrocautery. Use electrocautery when necessary at minimum power and assisted by a vacuum cleaner.

DISCUSSION

Initially called coronavirus, now called SARS-CoV-2, it appeared in Wuhan, China then spread throughout the world. On March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a state of a global pandemic. In Brazil, we had the first case diagnosed in February, and the last official number, until the conclusion of this review, was 310,087 confirmed cases and 20,047 deaths94. Brazil’s mortality rate is 8.5 deaths/100 thousand inhabitants, with 18.5 in the North and 1.2 in the South.

There have been two major coronavirus epidemics in the recent past, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in China in 2002 and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in the Middle East in 2012. These two epidemics had higher lethality rates, 11%, and 34.3%, respectively, but were much less comprehensive. The new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, although less lethal, has higher infectivity and greater inter-human transmission capacity, characteristics that were essential for the installation of the pandemic, and the fact that the world is increasingly globalized. The lethality of COVID-19 was estimated at 2.3%, but it is probably overestimated since asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic cases (estimated at 80%) are not computed. The transmission rate (R0) is at least 2 to 2.5 people infected per infected patient, and this number only decreases with social isolation or the development of population immunity85. Controlling contagion is even more difficult, considering that it is estimated that between 30 and 50% of transmissions occur by pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic patients for an uncertain time. The forms of transmission found so far include direct contact, aerosols, and fomites (contaminated surfaces)95,96. Table 1 shows COVID-19’s half-life and maximum residence time on surfaces. A lipid layer surrounds the virus, and the decontamination guidelines must follow official disinfection protocols. Any form of detergent or disinfectant is known to be effective against COVID-19.

| Surface | Average life (h) | Maximum time (h) |

|---|---|---|

| Aerosols | 1.5 | 3 |

| Plastic | 6.8 | 72 |

| Cardboard | 4 | 24 |

| Copper | 1.5 | 4 |

| Stainless steel | 5.6 | 48 |

Clinical condition

Initially, the virus colonizes the oropharynx and nasopharynx, and, from the fifth day on, it is already found in the trachea and bronchi. The symptoms are very diverse, and 80% of patients have mild symptoms or none at all. The most frequent symptoms are described in Table 2. COVID-19 is now considered a systemic disease and not just a respiratory illness. Lethality is higher in risk groups, but the evolution is uncertain, even in individuals outside the risk group. The worsening of the condition may be associated with alteration in coagulation, with microemboli and embolisms, and changes in liver function. When altered, the complete normalization of lung function is not yet defined, but the disease does not appear to leave sequelae.

| Symptom | % |

|---|---|

| Sore throat | 12.4 |

| Nasal congestion | 3.7 |

| Anosmia | 40 |

| Fever | 85.6 |

| Cough | 68.7 |

| Tiredness | 39.4 |

| Myalgia | 15.6 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 6.8 |

| Diarrhea | 5.3 |

Tests for COVID-19

One of the measures adopted for screening for elective patients’ hospitalization is the testing of both the medical team and the patient. However, several considerations regarding the sensitivity of the tests available vary according to the methodology used in the tests and their manufacturers.

RT-PCR (COVID-19)

The exam identifies a specific RNA sequence for COVID-19, present in both the active virus and a fragment of the virus. It is collected in the nasopharynx and oropharynx, where it is present and detectable between the third and seventh days after the appearance of symptoms. Sensitivity in asymptomatic patients is very low and therefore has a high false-negative rate. We cannot be sure that the patient who comes to the office or hospital is not infected if the result is negative. This creates risk for the team and makes the health service a vector of contamination since COVID-19 can be observed dispersed in the air within 3 hours after the patient remains in the environment. Every asymptomatic patient with a negative or untested test should be considered a potential carrier of COVID-19.

Serology (IgM, IgA, and IgG)

The presence of IgM and IgA, which indicate recent infection, can be detected from the fifth day of infection onset and IgG, produced by the body later, from the second week. IgG patients can be considered cured, but there is a discussion of IgG’s ability to confer or indicate permanent protection. And it is not sure whether even immune, the patient could not be colonized and transmits any viruses in the oronasopharynx. The convalescent COVID-19 patient is potentially protected and will probably not be a chronic carrier of the virus, but more scientific evidence is lacking. Therefore, the care of social distance and hygiene of cured patients and health professionals must be the same. There is no “immune passport” that provides 100% security. Table 3 illustrates the interpretation of serology.

| Result | Clinical Meaning | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | IgM | IgG | |

| Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Positive | Negative | Negative | Infection. |

| Positive | Positive | Negative | Initial stage of infection. |

| Positive | Positive | Positive | Active stage of infection. |

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Final stage of infection. |

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Initial phase with false negative PCR. Repeat PCR for confirmation. |

| Negative | Negative | Positive | Previous contact. |

| Negative | Positive | Positive | Evolving infection. Repeat PCR. |

Source: www.fleury.com.br

The rapid tests used have helped to understand better the prevalence of infection in different locations around the world. These tests detect both IgM and IgG, but do not discriminate against them. However, a validation study carried out at the Hospital das Clínicas of FMUSP, shows that when using the blood from the fingertip, we obtain test sensitivity of only about 55%, which increases to the excellent rate of 96% when we use their serum patients in the test1.

Telemedicine

Still, with temporary legislation, the CFM determines that during the COVID-19 outbreak, telemedicine can be used for tele-orientation, guiding, or referring patients in isolation, telemonitoring, or even teleconsultation between health professionals98. In other countries, the use of telemedicine has been widely used to prevent the patient from attending the office, in the form of pre-consultation and screening. Among the subspecialties of plastic surgery, in oculoplasty69,99, telemedicine has shown to be feasible in evaluating the patient. We emphasize the importance of completing informed consent for telemedicine (see the model in Annex 3).

Clinic

We have to provide maximum protection to our employees and patients, but we question whether this would be possible in the case of COVID-19. The protection of both staff and our patients depends on adaptations already established in protocols.

• The virus can remain on surfaces for a long time (Table 1). And the disinfection of the environment must be carried out between visits.

• Remove ornaments, plants, and magazines.

• Remove material and objects on benches and tables.

• Acrylic protection for reception or limit 1.5m distance from reception.

• Increase space between chairs. The recommended minimum distance is 3m between people.

• Reduced schedule.

• Environment disinfection:

• 70% alcohol in equipment;

• Sodium hypochlorite (bleach) 0.1 to 0.5% for surfaces.

Consultation

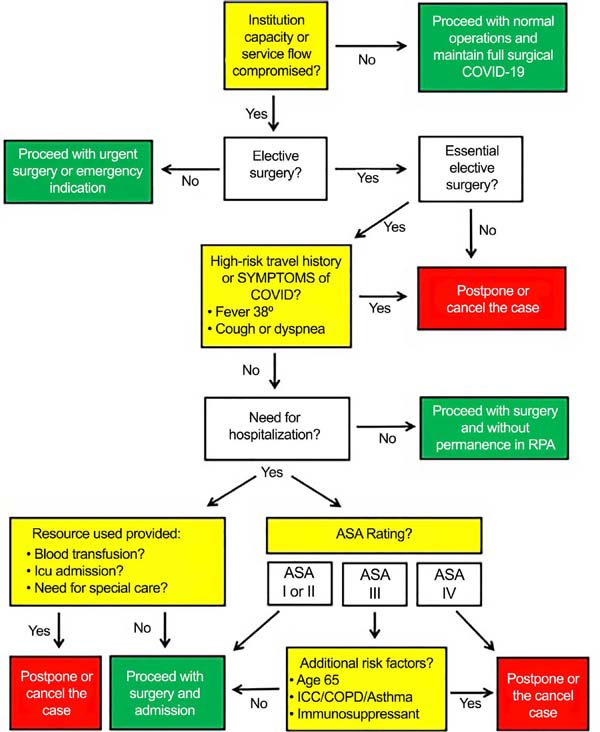

Medical attention (Figure 1):

• Pre-consultation by telemedicine. Check the real need for the patient to have to attend the health service. Sign a consent form for telemedicine.

• Send informational material and guidance for conduct and new care adopted to the patient by email or WhatsApp (Appendix 1): https://portal.fiocruz.br/coronavirus/material-para-download2.

• Online questionnaire (triage card) or email (Appendix 2).

• Screening for COVID-19.

• The patient should remove gloves and mask when entering the clinic, put in a plastic bag, and wash hands. The clinic must provide new masks.

• Mandatory use of shoe covers. The ideal would be to use an automatic plumber to avoid contact with shoes.

• Informed consent for COVID-19. Even with the signed informed consent, the virus’s uncertainties do not guarantee safety for the professional100 (Annex 3).

• The patient is only allowed to enter the clinic at the appointed time.

• Do not bring companions (except in specific cases).

Staff

• Exhaustive training of staff and requirement to comply with the guidelines: https://portal.fiocruz.br/coronavirus/material-para-download2

• Staff mask should be with a filter, like the N-95. Surgical masks do not entirely protect. Whatever the procedure, the N-95 must be used.

• Face shield for total face protection.

• Hand brushing early in the day.

• Disposable apron.

• Shoe covers.

• Gloves.

• Cap.

• Gel alcohol in all environments.

CONCLUSION

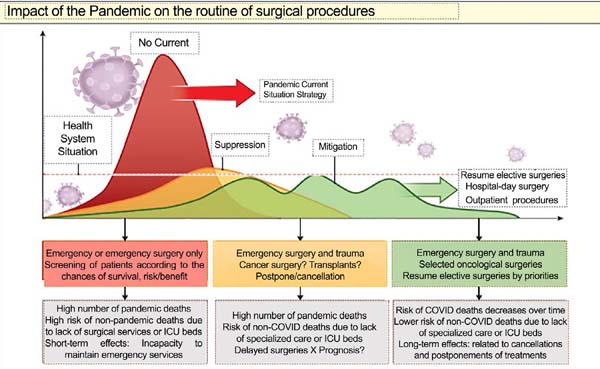

There is a profusion of editorials and articles establishing rules and algorithms for indicating or suspending surgical procedures. The suspension of mass surgeries, as occurs worldwide, should have still immeasurable consequences, both health and economic, including worsening the patient’s surgical condition because of confinement. The ideal situation for resuming our activities’ normality is not yet visible on the horizon, as shown in the graph in Figure 2 46.

In the world literature, there is no recommendation other than this at the moment: POSTERGING NON-ESSENTIAL ELECTIVE SURGERIES. Even knowing our patients’ health repercussions and economics for keeping us away from daily activities, we are facing a pandemic without limits or positive consequences. Our practice is based on the principle: primo non nocere. Based on evidence found in the literature:

• Follow the guidance of the government and professional bodies.

• Slowly open the office when the pandemic is under control.

• Screening before the face-to-face consultation with a questionnaire by phone, e-mail, or electronic message. Adopt telemedicine as a primary tool for screening and diagnosis when possible.

• Provide written information on safety protocols and updates on the pandemic to prevent further contact between staff and patients. Downloadable materials available at https://portal.fiocruz.br/coronavirus/material- para-download2

• Safety protocols for patients.

• Personal protective equipment is suitable for staff.

• Do not forget that COVID-19 can be considered an accident at work;

• The smaller the number of individuals in the environment, the lower the risk of transmission.

• We created a flow chart to assist in decisions regarding the indication of plastic surgery (Figure 3).

REFERENCES

1. Gorbalenya AE, Snijder EJ, Spaan WJ. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus phylogeny: toward consensus. J Virol. 2004 Aug;78(15):7863-6.

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2020; [acesso em 2020 mai 22]. Disponível em: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332151/nCoVsitrep15May2020-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

3. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270-3.

4. Ademuyiwa AO, Bekele A, Berhea AB, Borgstein E, Capo-Chichi N, Derbew M, et al. COVID-19 preparedness within the surgical, obstetric and anesthetic ecosystem in Sub Saharan Africa. Ann Surg. 2020 Apr 13; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003964

5. Lancaster EM, Sosa JA, Sammann A, Pierce L, Shen W, Conte MC, et al. Rapid response of an Academic Surgical Department to the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for patients, surgeons, and the community. J Am Coll Surg. 2020 Jun;230(6):1064-73.

6. Brat GA, Hersey S, Chhabra K, Gupta A, Scott J. Protecting surgical teams during the COVID-19 outbreak: a narrative review and clinical considerations. Ann Surg. 2020 Apr 17; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003926

7. Mirza AK. Perspectives on vascular surgical practice change due to COVID-19 at a nonacademic tertiary care center. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Apr;S0741-5214(20):30592-9.

8. Massey PA, McClary K, Zhang AS, Savoie FH, Barton RS. Orthopaedic surgical selection and inpatient paradigms during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020 Apr;28(11):436-50.

9. Wick EC, Pierce L, Conte MC, Sosa JA. Operationalizing the operating room: ensuring appropriate surgical care in the era of COVID-19. Ann Surg. 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004003

10. Service BC, Collins AP, Crespo A, Couto P, Gupta S, Avilucea F, et al. Medically necessary orthopaedic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: safe surgical practices and a classification to guide treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 May 13; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.20.00599

11. Ross SW, Lauer CW, Miles WS, Green JM, Christmas AB, May AK, et al. Maximizing the calm before the storm: tiered surgical response plan for novel coronavirus (COVID-19). J Am Coll Surg. 2020(6):1080-91.e3.

12. Brindle ME, Gawande A. Managing COVID-19 in surgical systems. Ann Surg. 2020 Mar 23; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003923

13. Bedard NA, Elkins JM, Brown TS. Effect of COVID-19 on hip and knee arthroplasty surgical volume in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020 Apr 24; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.060

14. Sheth PD, Simons JP, Robichaud DI, Ciaranello AL, Schanzer A. Development of a surgical workforce access team in the battle against COVID-19. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Apr 24; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.493

15. Howe JR, Bartlett DL, Tyler DS, Wong SL, Hunt KK, DeMatteo RP, et al. COVID-19 Guideline Modifications as CMS Announces "Opening Up America Again": comments from the Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020 May 8; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08565-9

16. Brindle ME, Doherty G, Lillemoe K, Gawande A. Approaching surgical triage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003992

17. Patriti A, Eugeni E, Guerra F. What happened to surgical emergencies in the era of COVID-19 outbreak? Considerations of surgeons working in an Italian COVID-19 red zone. Updates Surg. 2020 Apr 23; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00779-6

18. Giulio M, Achilli P, Dario M. An underestimated "false negative COVID cholecystitis" in Northern Italy and the contagion of a surgical ward: it can happen everywhere. Updates Surg. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

19. Alemanno G, Tomaiuolo M, Peris A, Batacchi S, Nozzoli C, Prosperi P. Surgical perspectives and patways in an emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Surg. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

20. Peloso A, Moeckli B, Oldani G, Triponez F, Toso C. Response of a European surgical department to the COVID-19 crisis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Apr;150:w20241.

21. Mayer HF, Persichetti P. Plastic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic times. Eur J Plast Surg. 2020 May 7; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-020-01685-1

22. Chisci E, Masciello F, Michelagnoli S. Creation of a vascular surgical hub responding to the COVID-19 emergency: the italian USL Toscana Centro model. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Apr 16; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.019

23. Kurihara H, Bisagni P, Faccincani R, Zago M. COVID-19 outbreak in Northern Italy: viewpoint of the Milan Area Surgical Community. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020 Mar 20; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000002695

24. Perrone AM, De Palma A, De Iaco P. Covid-19 global pandemic: options for management of gynecologic cancers. The experience in surgical management of ovarian cancer in the second highest affected Italian region. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 May 6; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2020-001489

25. Marano L, Marrelli D, Roviello F. Cancer care under the outbreak of COVID-19: a perspective from Italian tertiary referral center for surgical oncology. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Apr 15; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.04.004

26. Ahmed S, Tan WLG, Chong YL. Surgical response to COVID-19 pandemic: a Singapore perspective. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(6):1074-77. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.003

27. Low TY, So JBY, Madhavan KK, Hartman M. Restructuring the surgical service during the COVID-19 pandemic: experience from a tertiary institution in Singapore. Br J Surg. 2020 May 14; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11701

28. Ng ASH, Chew MH, Charn TC, Wong MK, Wong WK, Lee LS. Keeping a cut above the coronavirus disease: surgical perspectives from a public health institution in Singapore during Covid-19. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(5):600-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.15904

29. Chew MH, Tan WJ, Ng CY, Ng KH. Deeply reconsidering elective surgery: worldwide concerns regarding colorectal surgery in a COVID-19 pandemic and a Singapore perspective. Singapore Med J. 2020 Apr 29; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2020070

30. Yeo D, Yeo C, Kaushal S, Tan G. COVID-19 and the General Surgical Department - measures to reduce spread of SARS-COV-2 among surgeons. Ann Surg. 2020 May 19; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003957

31. Wang H, Wu J, Wei Y, Zhu Y, Ye D. Surgical volume, safety, drug administration, and clinical trials during COVID-19: single-center experience in Shanghai, China. Eur Urol. 2020 Apr 21; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.026

32. Ma FH, Hu HT, Tian YT. [Surgical treatment strategy for digestive system malignancies during the outbreak of COVID-19]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2020 Mar;42(3):180-3.

33. Li Y, Qin JJ, Wang Z, Yu Y, Wen YY, Chen XK, et al. [Surgical treatment for esophageal cancer during the outbreak of COVID-19]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2020 Apr;42(4):296-300.

34. Zhao Z, Li M, Liu R. Suggestions on surgical treatment during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Biosci Trends. 2020 Apr 27; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2020.03098

35. Balibrea JM, Badia JM, Rubio Pérez I, Martin Antona E, Alvarez Pena E, Garcia Botella S, et al. Surgical management of patients with COVID-19 infection. Recommendations of the Spanish Association of Surgeons. Cir Esp. 2020 May;98(5):251-9.

36. Wang L, Gong R, Yu S, Qian H. Social media impact on a plastic surgery clinic during shutdown due to COVID-19 in China. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2020 May;22(3):162-3.

37. Xu J, Xu QH, Wang CM, Wang J. Psychological status of surgical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Apr;288:112955.

38. Tan YT, Wang JW, Zhao K, Han L, Zhang HQ, Niu HQ, et al. Preliminary recommendations for surgical practice of neurosurgery department in the central epidemic area of 2019 coronavirus infection. Curr Med Sci. 2020 Apr;40(2):281-4.

39. Ozturk CN, Kuruoglu D, Ozturk C, Rampazzo A, Gurunian Gurunluoglu R. Plastic surgery and the Covid-19 pandemic: a review of clinical guidelines. Ann Plast Surg. 2020 Apr 30; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/sap.0000000000002443

40. Kuang D, Xu SP, Hu Y, Liu C, Duan YQ, Wang GP. [The pathological changes and related studies of novel coronavirus infected surgical specimen]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020 Mar;49(0):E008.

41. Liu Z, Ding Z, Guan X, Zhang Y, Wang X, Khan JS. Optimizing response in surgical systems during and after COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from China and the UK - Perspective. Int J Surg. 2020 Jun;78:156-9.

42. Qing H, Yang Z, Shi M, Zhang Z. New evidence of SARS-CoV-2 transmission through the ocular surface. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020 May 4; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-020-04726-4

43. Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann Surg. 2020 Mar 26; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003924

44. Zhou Y, Xu H, Li L, Ren X. Management for patients with pediatric surgical disease during the COVID-19 epidemic. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020 Jun;36(6):751-2.

45. Huang G. The importance of preventing COVID-19 in surgical wards cannot be overemphasized. Br J Surg. 2020 Jun;107(7):e198.

46. Soreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB, Schnitzbauer AA, Line PD, Lai PBS, et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg. 2020 Apr 30; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11670

47. Hu YJ, Zhang JM, Chen ZP. Experiences of practicing surgical neuro-oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurooncol. 2020 Apr 10; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-020-03489-6

48. Zhang X, Chen X, Chen L, Deng C, Zou X, Liu W, et al. The evidence of SARS-CoV- 2 infection on ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2020;18(3):360-2.

49. Ma QX, Shan H, Zhang CM, Zhang HL, Li GM, Yang RM, et al. Decontamination of face masks with steam for mask reuse in fighting the pandemic COVID-19: experimental supports. J Med Virol. 2020 Apr 22; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25921

50. He Y, Wei J, Bian J, Guo K, Lu J, Mei W, et al. Chinese Society of Anesthesiology expert consensus on anesthetic management of cardiac surgical patients with suspected or confirmed Coronavirus disease 2019. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020 Mar;34(6):1397-401.

51. Rubino F, Cohen RV, Mingrone G, le Roux CW, Mechanick JI, Arterburn DE, et al. Bariatric and metabolic surgery during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: DSS recommendations for management of surgical candidates and postoperative patients and prioritisation of access to surgery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 May 7; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30157-1

52. Wang JZ, Zhang RY, Bai J. An anti-oxidative therapy for ameliorating cardiac injuries of critically ill COVID-19-infected patients. Int J Cardiol. 2020 Apr 6; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.04.009

53. Lei S, Jiang F, Su W, Chen C, Chen J, Mei W, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Apr;21:100331. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331

54. Unlu C, Ustun Y. Approach to surgical interventions during Covid-19 pandemic in Turkey. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Apr 25; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.026

55. Armstrong A, Jeevaratnam J, Murphy G, Pasha M, Tough A, Conway-Jones R, et al. A plastic surgery service response to COVID-19 in one of the largest teaching hospitals in Europe. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020 Apr 21; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2020.03.027

56. Iacobucci G. Covid-19: all non-urgent elective surgery is suspended for at least three months in England. BMJ. 2020 Mar;368:m1106.

57. Brito LGO, Ribeiro PA, Silva Filho AL, COVID FBGSGf. How Brazil is dealing with COVID-19 pandemic arrival regarding elective gynecological surgeries. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Apr 25; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.028

58. Giunta RE, Frank K, Costa H, Demirdover C, di Benedetto G, Elander A, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on plastic surgery in Europe - an ESPRAS survey. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2020 May 11; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1169-4443

59. Rana RE, Ather MH. Change in surgical practice amidst COVID 19; example from a tertiary care centre in Pakistan. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.04.035

60. Basman C, Kliger CA, Pirelli L, Scheinerman SJ. Management of elective aortic valve replacement over the long term in the era of COVID-19. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;57(6):1029-31.

61. Engelman DT, Lother S, George I, Funk DJ, Ailawadi G, Atluri P, et al. Adult cardiac surgery and the COVID-19 pandemic: aggressive infection mitigation strategies are necessary in the operating room and surgical recovery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020 Apr 27; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.007

62. Vilallonga R, Blanco-Colino R, Carrasco MA. Reply to the article "Bariatric surgical practice during the initial phase of COVID-19 outbreak". Obes Surg. 2020 May 13; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04678-y

63. Aminian A, Kermansaravi M, Azizi S, Alibeigi P, Safamanesh S, Mousavimaleki A, et al. Bariatric surgical practice during the initial phase of COVID-19 outbreak. Obes Surg. 2020 Apr 20; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04617-x

64. Arndt C, Delyfer MN, Kodjikian L, Leveziel N, Zech C. [How to approach management of surgical vitreoretinal disease during the SARS-CoV-2 Covid-19 pandemic?]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020 Apr 30; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfo.2020.04.011

65. Shih KC, Wong JKW, Lai JSM, Chan JCH. The case for continuing elective cataract surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000225

66. Shokri T, Lighthall JG. Telemedicine in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic: implications in facial plastic surgery. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2020 May/Jun;22(3):155-6.

67. Gentileschi S, Caretto AA, Tagliaferri L, Salgarello M, Peris K. Skin cancer plastic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.04.048

68. Unadkat SN, Andrews PJ, Bertossi D, D'Souza A, Joshi A, Shandilya M, et al. Recovery of elective facial plastic surgery in the post-Coronavirus disease 2019 Era: recommendations from the European Academy of Facial Plastic Surgery Task Force. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2020 May 14; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1089/fpsam.2020.0258

69. Langer PD, Bernardini FP. Oculofacial plastic surgery and the COVID-19 pandemic: current reactions and implications for the future. Ophthalmology. 2020 Apr 26; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.035

70. Singh P, Ponniah A, Nikkhah D, Mosahebi A. The effects of a novel global pandemic (COVID-19) on a plastic surgery department. Aesthet Surg J. 2020 Apr 29; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa074

71. Kamolz LP, Spendel S. [The COVID-19 pandemia and its consequences for plastic surgery and hand surgery: a comment from the Graz University Hospital]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2020 May 13; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1165-6799

72. Giunta RE, Frank K, Moellhoff N, Braig D, Haas EM, Ahmad N, et al. [The COVID- 19 pandemia and its consequences for plastic surgery and hand surgery]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2020 Apr 28; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1163-9009

73. Al-Benna S, Gohritz A. Availability of COVID-19 information from National Plastic Surgery Society websites. Ann Plast Surg. 2020 May 4; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002447

74. Doussot A, Heyd B, Lakkis Z. We asked the experts: how do we maintain surgical quality standards for enhanced recovery programs after cancer surgery during the COVID-19 outbreak?. World J Surg. 2020 Apr 26; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05546-7

75. Cardoso P, Rodrigues-Pinto R. Surgical management of bone and soft tissue sarcomas and skeletal metastases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Apr 18; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.04.027

76. Akladios C, Azais H, Ballester M, Bendifallah S, Bolze PA, Bourdel N, et al. [Guidelines for surgical management of gynaecological cancer during pandemic COVID- 19 period - FRANCOGYN group for the CNGOF]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2020;48(5):444-7.

77. Sell NM, Silver JK, Rando S, Draviam AC, Mina DS, Qadan M. Prehabilitation telemedicine in neoadjuvant surgical oncology patients during the novel COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Ann Surg. 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004002

78. Head A, Neck Surgery Treatment Guidelines C, Maniakas A, Jozaghi Y, Zafereo ME, Sturgis EM, et al. Head and neck surgical oncology in the time of a pandemic: subsite-specific triage guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020 Jun;42(6):1194-201.

79. Day AT, Sher DJ, Lee RC, Truelson JM, Myers LL, Sumer BD, et al. Head and neck oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic: reconsidering traditional treatment paradigms in light of new surgical and other multilevel risks. Oral Oncol. 2020 Apr 6; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104684

80. Classe JM, Dolivet G, Evrard S, Ferron G, Lecuru F, Leufflen L, et al. [French Society for Surgical Oncology (SFCO) guidelines for the management of surgical oncology in the pandemic context of COVID 19]. Bull Cancer. 2020 Apr 6; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bulcan.2020.03.010

81. Civantos FJ, Leibowitz JM, Arnold DJ, Stubbs VC, Gross JH, Thomas GR, et al. Ethical surgical triage of head and neck cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26229

82. Ginsburg KB, Curtis GL, Timar RE, George AK, Cher ML. Delayed radical prostatectomy is not associated with adverse oncological outcomes: implications for men experiencing surgical delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Urol. 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000001089

83. Mazzaferro V, Danelli P, Torzilli G, Busset MDD, Virdis M, Sposito C. A combined approach to priorities of surgical oncology during the COVID-19 epidemic. Ann Surg. 2020 May 1; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004005

84. Ghannam A, Souadka A. Beware of time delay and differential diagnosis when screening for symptoms of COVID-19 in surgical cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2020 May 8; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.032

85. World Health Organization (WHO). Surveillance strategies for COVID-19 human infection. Geneva: WHO; 2020.

86. American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). 2018 - National plastic surgery statistics. USA: ASPS; 2018.

87. Conselho Regional de Medicina do Estado do Acre (CRM-AC). Resolução CRM-AC n° 01/2020. Recomenda o retorno de procedimentos médicos, cirurgias e consultas no âmbito da FUNDHACRE. Rio Branco (AC): CRM-AC; 2010.

88. Stahel PF. How to risk-stratify elective surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Patient Saf Surg. 2020 Mar;14:8.

89. Dietz JR, Moran MS, Isakoff SJ, Kurtzman SH, Willey SC, Burstein HJ, et al. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment, and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic breast cancer consortium. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181(3):487-97.

90. Aminian A, Safari S, Razeghian-Jahromi A, Ghorbani M, Delaney CP. COVID-19 outbreak and surgical practice: unexpected fatality in perioperative period. Ann Surg. 2020 Mar 26; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003925

91. Lepre L, Costa G, Virno VA, Dalsasso G, Campa RD, Clavarino F, et al. Acute care surgery and post-operative COVID-19 pneumonia: a surgical and environmental challenge. ANZ J Surg. 2020 Apr 25; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.15962

92. Diaz A, Sarac BA, Schoenbrunner AR, Janis JE, Pawlik TM. Elective surgery in the time of COVID-19. Am J Surg. 2020 Apr 16; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.04.014

93. Collaborative COVIDSurg. Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020 Apr 15; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11646

94. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Painel coronavírus. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2020; [acesso em 2020 mai 21]. Disponível em: https://covid.saude.gov.br/

95. Ong SWX, Tan YK, Chia PY, Lee TH, Ng OT, Wong MSY, et al. Air, Surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA. 2020 Apr;323(16):1610-2.

96. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr;382(16):1564-7.

97. Lovato A, Filippis C. Clinical presentation of COVID-19: a systematic review focusing on upper airway symptoms. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020 Apr 13; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561320920762

98. Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM). Oficio CFM no 1756/2020 - COJUR. Telemedicina CFM. Brasília (DF): CFM; 2020.

99. Mak ST, Yuen HK. Oculoplastic surgery practice during the COVID-19 novel coronavirus pandemic: experience sharing from Hong Kong. Orbit. 2020 Apr 15; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2020.1754435

100. Bryan AF, Milner R, Roggin KK, Angelos P, Matthews JB. Unknown unknowns: surgical consent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2020 Apr 19; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003995

APPENDIX

Source: Adapted from recommendations of the European Society of Plastic Surgery (EURAPS)68.

1. Hospital São Luiz Itaim, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2. Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Plastic Surgery Department, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

3. University of the São Paulo, Clinical Immunology and Allergy Division, São Paulo,

SP, Brazil.

BLB Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

CI Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

DPN Final manuscript approval, Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing

PGB Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Final manuscript approval, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

Corresponding author: Beatriz Lassance Brito, Rua Jesuíno Arruda, 676, Itaim Bibi, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 04532-082. E-mail: beatriz@lassance.com

Article received: May 20, 2020.

Article accepted: May 27, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter