Review Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Breast asymmetry: literature review and a new proposal for clinical classification

Assimetria mamária: revisão da literatura e nova proposta de classificação clínica

ABSTRACT

Breast asymmetry is a prevalent diagnosis that has several surgical modalities for its treatment. The correct diagnosis, taking into account the existing classification systems, is imperative for achieving the best results. The leading and most accepted proposals for the classification and treatment of breast asymmetries were raised through the literature review. These available classifications date from the 60s and 70s and need to be updated to the current clinical context. A more simplified and reproducible classification was proposed after a comprehensive literature review, considering the most frequent asymmetries in aesthetic plastic surgery offices, with their respective treatment guides. Five groups were created: 1 - hypotrophic breasts with volume asymmetry; 2 - hypotrophy with volume and contour asymmetry; 3 - normotrophic, ptotic breasts and with no desire to increase the volume; 4 - normotrophic, ptotic breasts and with a desire to increase the final volume; 5 - asymmetric and hypertrophic breasts. Based on the clinical findings, a treatment algorithm was created for each subtype of asymmetry, including in this arsenal, breast implants of different volumes, mastopexies, reduction mammoplasty, and fat grafting. It is important to emphasize that breast asymmetry is the rule and not the exception, therefore, it is a reason for patient dissatisfaction and a challenge for the plastic surgeon.

Keywords: Breast; Silicone elastomers; Breast implant; Mammoplasty; Classification.

RESUMO

A assimetria mamária é um diagnóstico prevalente com diversas modalidades cirúrgicas para seu tratamento. O correto diagnóstico, levando-se em conta os sistemas de classificação existentes é imperativo para que os melhores resultados sejam alcançados. Através de revisão da literatura foram levantadas as principais e mais aceitas propostas de classificação e tratamento das assimetrias mamárias. Estas classificações disponíveis datam da década de 60 e 70 e carecem de atualização para o contexto clínico atual. Após ampla revisão da literatura foi proposta uma classificação mais simplificada e reprodutível, levando-se em conta as assimetrias mais frequentes nos consultórios de cirurgia plástica estética, com seus respectivos guias de tratamento. Cinco grupos foram criados: 1 - mamas hipotróficas com assimetria de volume; 2 - hipotrofia com assimetria de volume e contorno; 3 - mamas normotróficas, ptóticas e sem desejo de aumento do volume; 4 - mamas normotróficas, ptóticas e com desejo de aumento do volume final; 5 - mamas assimétricas e hipertróficas. Baseado nos achados clínicos, foi criado um algoritmo de tratamento para cada subtipo de assimetria, incluindo neste arsenal, próteses mamárias de volumes diferentes, mastopexias, mamoplastia redutoras, além da lipoenxertia. Importante ressaltar que a assimetria mamária é a regra e não a exceção, entretanto, é motivo de insatisfação das pacientes e um desafio para o cirurgião plástico.

Palavras-chave: Mama; Elastômeros de silicone; Implante mamário; Mamoplastia; Classificação

INTRODUCTION

In addition to their role in the physiology of lactation, breasts are related to femininity, sensuality, and self-esteem. Variations in normality, shape, volume, or position affect women psychologically and are an essential cause of demand in plastic surgery offices1.

The recognition of the importance of breast asymmetry dates from 1968 when the author describes the surgical treatment modalities2. The interest in creating a classification was growing and, in 1976, Elsahy2, proposed a morphological classification of breast asymmetries, in order to facilitate preoperative planning. Later, in 19843, Vandenbussche subdivided them as to their etiology into four types (1 - congenital, 2 - primary, 3 - secondary, and 4 - tertiary), concluding that type 2 asymmetry was the most frequent2. In 2006, another group analyzed 177 patients with breast asymmetries to propose a classification and its treatment4.

These works contributed to the understanding of breast asymmetries and their treatment, but a more simplified and reproducible update to clinical practice, added to the new therapeutic modalities available, is a medical need that has not yet been met. Gross anomalies, such as Poland’s syndrome, are widely discussed, but there is an evident need to detail Vandenbussche’s type 23, not only for its incidence but also because it is the subtype that most refer to the aesthetic character of these abnormalities. Another critical milestone to be considered was the consecration of fat grafting within the therapeutic arsenal of breast surgeries, which had its condemnation phase, but is now widely accepted, both in reconstructive and aesthetic surgeries5.

OBJECTIVE

The present work proposes a practical and simplified classification of breast asymmetries with the highest incidence in plastic surgery offices, and with a more accurate diagnosis, it proposes to guide surgical treatment.

METHODS

The textual search was carried out on PubMed with the terms “breast” and “asymmetry” and articles that had the proposal to classify breast asymmetries were considered eligible. Also included were articles dealing with the subject of asymmetry even though it did not propose a classification. After confronting the information collected about classification and treatment, an attempt was made to make the classification more simplified and reproducible at the clinical practice, taking into account, in this new classification, the patient’s possible interest in the final volume of the breasts and the incorporation of fat grafting, as a therapeutic arsenal. Chest asymmetries, as described in the Vandenbussche classification, in 19843, despite its high relevance and limitations for better results in correcting breast asymmetries, were not included in the new classification proposal, since plastics surgeons do not address most of them.

RESULTS

In Chart 1, we see the principal authors with their respective classification proposals.

| Hueston (1968)1 (review) | 1 - Unilateral aplasia; |

| 2- Unilateral hypoplasia; | |

| 3- Hypertrophy; | |

| 4- Destruction of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC); | |

| 5- Mastectomy. | |

| Elsahy (1976)2 | 1- Unilateral hypertrophy; |

| 2- Unilateral hypotrophy; | |

| 3- Hypo and hypertrophy. | |

| 4- Bilateral hypertrophy; | |

| 5- Bilateral hypotrophy. | |

| Vandenbussche (1984)3 (150 patients) | 1- Congenital; |

| 2- Primary; | |

| 3- Secondary; | |

| 4- Tertiary. | |

| Araco et al. (2006)4 (177 patients) | 1- Bilateral hypertrophy (n = 30); |

| 2- Hypertrophy, normotrophy (n = 15); | |

| 3- Hypertrophy with amastia or hypoplasia (n = 10); | |

| 4- Amastia or hypoplasia, normal contralateral (n = 5); | |

| 1- Bilateral hypoplasia (n = 81); | |

| 2- Unilateral ptosis (n = 36). |

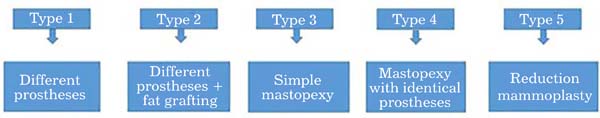

In the classification proposed in this work (Figure 1), the first group presents hypotrophic breasts with volume asymmetry (type 1), the second group presents volume and shape asymmetry in hypotrophic breasts (type 2). Normotrophic breasts are included in types 3 and 4, they have breast ptosis and have been subdivided into those who wish to maintain volume (type 3) and those with a desire for volumetric increase (type 4). And finally, asymmetric hypertrophic breasts in type 5.

| Type 1 | Hypotrophic breasts with volume asymmetry | |

| Type 2 | Hypotrophic breasts with volume and contour asymmetry | |

| Type 3 | Normotrophic breasts, with ptosis, with no desire for volumetric increase | |

| Type 4 | Normotrophic breasts, with ptosis, and desire for volumetric increase | |

| Type 5 | Hypertrophic asymmetric breasts |

After the classification described in Figure 1 and based on the treatments recommended by the medical literature, the surgical planning protocol was created and used for the therapeutic decision, as shown in Figure 2.

In type 1, the breasts are hypotrophic and have a similar contour. The simple prostheses placement of different volumes is enough. Particular attention should be given when measuring breast volume and estimating which difference in volume and/or profile to use. Most of the time, the experience of the surgeon associated or not with the use of molds is sufficient. Techniques that use Archimedes’ law to measure volume turn out to be of difficult clinical applicability6 and three-dimensional scanning software is still poorly accessible to most surgeons.

In type 2, simply placing different implants is not enough. Some areas of the breast, after the placement of the prostheses, deserve a thorough analysis with the stretcher in an elevated headboard position and the areas for fat grafting demarcated. In this situation, we may have a volumetric deficit in any of the breast poles or in the entire breast. The fat preparation technique ranges from simple decanting7 to the Coleman technique (1995)8 and the fat infiltration performed with 1.8mm cannulas in the subcutaneous and intramammary plane4,8

In type 3, the patient has ptosis and is satisfied with the volume of the breasts and/or does not want the use of implants. In this case, simple mastopexy is performed, using the surgeon’s experience technique, drying the mammary parenchyma of the largest breast sufficiently for volumetric symmetrization9,10.

Type 4 also presents ptosis and differs from type 3 only by the patient’s desire to increase the final volume, and, for this reason, breast implants are used during a mastopexy. Priority is given to identical implants, and symmetrization is done by manipulating the breast parenchyma. In this group, refinements with fat grafting can also be of great value.

In type 5, there is asymmetry with evident breast hypertrophy, and, in this case, there is an indication of symmetrization through reduction mammoplasty with recognized techniques(10,11 )such as Pitanguy, in 196712 and Silveira Neto, in 197613.

RESULTS

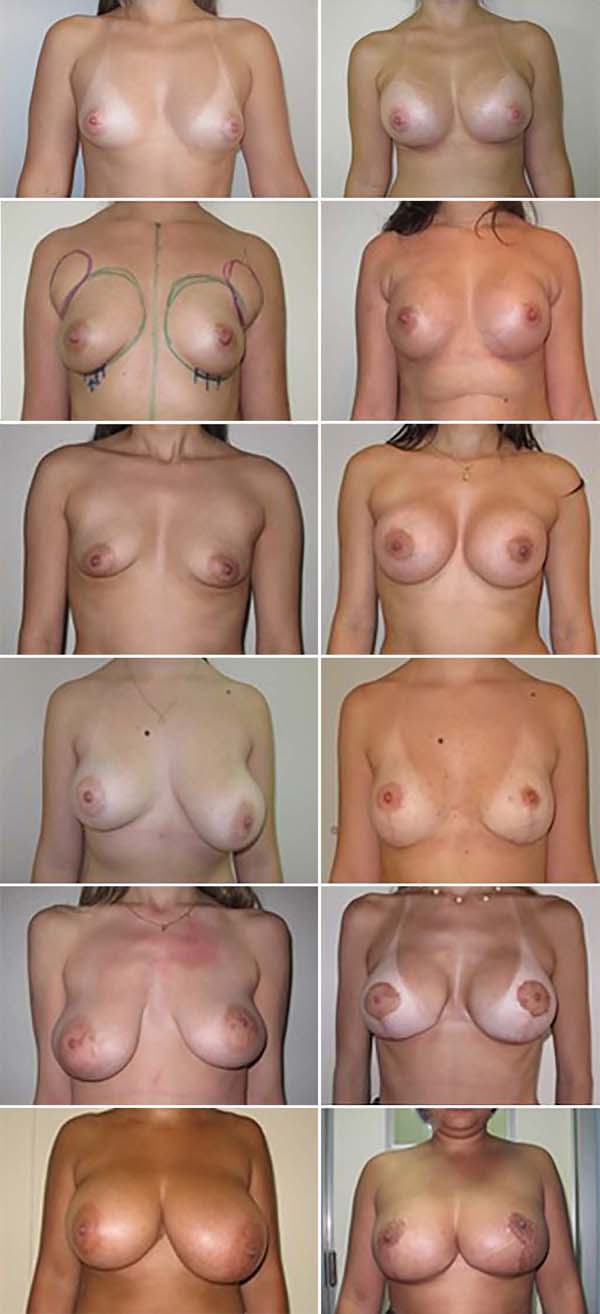

In Figure 3A, there is a type 1 breast asymmetry, whose treatment was performed with a Mentor 300ml breast prosthesis (subfascial plane) on the right and 275ml on the left, both with a high profile.

In Figure 3B, we have an asymmetry of volume and contour, configuring type 2. On the left, the surgical mark and the liposuction area in the underarm region are shown. In this case, the prostheses (subfascial plane) used were quite different: textured Silimed 230ml high model on the right and 305ml extra high on the left, in addition to global fat grafting on the left and medial pole on the right. In detail, the surgical marking and liposuction area.

Figure 3C shows another example of type 2 asymmetry, but asymmetry predominated in contour and mammary fold. In this case, it was decided to keep the same prosthesis textured, 330ml extra high Silimed (subfascial plane), mammary fold lowering, and fat grafting of the lower poles of both breasts.

In Figure 3D, there is a case of type 3 asymmetry, where there is breast ptosis and the patient’s desire to keep the breast volume smaller. Mastopexy performed using the Pigossi technique, resulting scar in inverted T.

In another case of type 4 asymmetry (Figure 3E), the patient has ptosis but wishes to increase the breast volume. It was indicated mastopexy with prosthesis and marking proposed by Pitanguy 196712, using a 200ml prosthesis in the subglandular plane.

Finally, a case of type 5 breast asymmetry (Figure 3F), in which there is evident breast hypertrophy with dense and ptotic breasts. We opted for the reduction mammaplasty technique with superomedial pedicle, a technique by Silveira Neto (1976)13.

DISCUSSION

As it is a frequent pathology and of unique importance in women’s self-esteem and well-being, breast asymmetry is a reason for the high demand in plastic surgery offices. The analysis of this pathology begins with adequate clinical evaluation of the patient, in all its aspects such as volume, contour, consistency, and presence of ptosis. The creation of classification systems facilitates the language between specialists, and the protocols guide the forms of treatment.

Obviously, each patient is unique and must be assessed individually, since breast asymmetry is considered the rule and not the exception. Several morphometric studies have attempted to establish fixed points for better breast evaluation. However, they presented limitations both in vivo and through photographs, as they were linear measures14. Despite these limitations, several of these parameters have been used since its publication in 1986, as the distance between the sternal furcula and the nipple, and the distance between the nipple and the mammary fold15. Perfect breast symmetry, even according to morphometry studies, is practically nonexistent in the pre- or postoperative period, but it is a reality and not a distortion of the patient’s self-image, therefore deserving its due respect. Brown et al., In 199916, demonstrated that the finding of asymmetry is more frequently reported in patients looking for reduction mammoplasty compared to patients looking for breast augmentation.

Classifications favor more accurate diagnoses and, when associated with treatment protocols, minimize the chances of errors due to inappropriate conduct. An example of this is the high incidence of postoperative breast asymmetry demonstrated in a retrospective study after breast augmentation surgery, concluding that preoperative systematizations are essential to minimize conduct errors17.

Stark’s work in 199118 demonstrates how classifications translate a universal language among surgeons. Its preoperative analysis was based on the classifications of Elsahy (1976)2 and Vandenbussche (1984)3, and the study aimed to propose an objective assessment of asymmetric breasts in the postoperative period using standardized measures18. The classification of Vandenbussche (1984)3 takes into account only the etiology of asymmetry (congenital, primary, secondary or tertiary), which is of great value for reconstructive surgery, but somewhat limited for aesthetic cases since the vast majority would fit in the congenital and primary etiologies. The classification of Elsahy (1976)2, on the contrary, assesses in detail the breast asymmetries from a clinical and morphological point of view, subdividing them into five main groups. Its limitation is the analysis complexity, with multiple possible associations involving breast trophism and not evaluating the patient’s desire regarding the change in her breast volume.

In 2006, Araco et al. noted the evident need for a new classification and, based on their sample of 177 patients, subdivided the asymmetries into six categories and proposed the respective treatment for each one. At work, however, there is no mention of fat grafting in its treatment algorithm as a valuable adjuvant therapy and does not mention the current and relevant desire of the patient regarding the final breast volume considered normotrophic4. Emphasizing the need for such classifications for better understanding, clinical analysis, and communication among professionals, Roxo et al., in 200919, proposed a classification and treatment of mammoplasty; however, this classification is limited to patients after massive weight loss.

A standardized language undoubtedly facilitates the discussion of cases and the exchange of experiences, guiding the conduct of the less experienced and making the dialogue with the patient in the preoperative medical consultation clearer.

CONCLUSION

The extensive review of the literature allowed the creation of a simpler and reproducible classification of breast asymmetries. It was added to the treatment protocols already established in this work, fat grafting as an adjunct in the treatment of asymmetries. The patient’s desire regarding the final volume of her breasts was also included.

REFERENCES

1. Hueston JT. Surgical correction of breast asymmetry. Aust NZJ Surg. 1968 Nov;38(2):112116.

2. Elsahy NI. Correction of asymmetries of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976 Jun;57(6):700-3.

3. Vandenbussche F. Asymmetries of the breast: a classification system. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1984;8(1):27-36.

4. Araco A, Gravante G, Araco F, Gentile P, Castrí F, Delogu D, et al. Breast asymmetries: a brief review and our experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2006 Mai/Jun;30(3):309-19.

5. Illouz YG, Sterodimas A. Autologous fat transplantation to the breast: a personal technique with 25 years of experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009 Set;33(5):706-15.

6. Stark B, Olivari N. Breast asymmetry: an objective analysis of postoperative results. Eur J Plast Surg. 1991;14:173-6.

7. Tezel E, Numanoglu A. Practical do-it-yourself device for accurate volume measurement of breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000 Mar;105(3):1019-23.

8. Coleman SR. Long-term survival of fat transplants: controlled demonstrations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995 Set/Oct;19(5):421-5.

9. Sakai RL, Tavares LC, Soares RA, Oliveira IN, Komatsu CA, Faiwichow L. Mastoplastia de aumento em mamas assimétricas: implantes de silicone + lipoenxertia. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(3 Supl 1):1-103.

10. Pigossi N, Andrade A, Calange H. Mamaplastia estética e funcional - experiência de 25 anos. Arq Catar Med. 1994;23:19-22.

11. Ariè G. Nova técnica em mamoplastia. Rev Lat Amer Cir Plást. 1975;3:28.

12. Pitanguy I. Surgical treatment of breast hypertrophy. Br J Plast Surg.1967;20(1):78-85.

13. Silveira Neto E. Mastoplastia redutora setorial com pedículo areolar interno. In: Anais do XIII Congresso Brasileiro de Cirurgia Plástica e I Congresso Brasileiro de Cirurgia Estética; Abr 1976, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. Porto Alegre (RS): SBCP; 1976.

14. Quieregatto PR, Hochman B, Furtado F, Ferrara SF, Machado SF, Sabino Neto M. Photographs for anthropometric measurements of the breast region. Are there limitations?. Acta Cir Bras. 2015;30(7):509-16.

15. Smith Junior DJ, Palin Junior WE, Katch VL, Bennet JE. Breast volume and anthropomorphic measurements: normal values. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986 Set;78(3):331-5.

16. Brown TP, Ringrose C, Hyland RE, Cole AA, Brotherston TM. A method of assessing female breast morphometry and its clinical application. Br J Plast Surg. 1999 Jul;52(5):355-9.

17. Rohrich RJ, Hartley W, Brown S. Incidence of breast and chest wall asymmetry in breast augmentation: a retrospective analysis of 100 patientes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003 Apr;111(4):1513-9;discussion:1520-3.

18. Stark B, Olivari N. Breast asymmetry: an objective analysis of postoperative results. Eur J Plast Surg. 1991;14(4):173-6.

19. Roxo CDP, Rodrigues EW, Roxo ACW, Aguiar EBP. Classificação e abordagem de mamas pós-grandes perdas ponderais. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009 Jul/Set;24(3):310-4.

1. Private Clinic, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2. Hospital das Clínicas, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, SP Brazil.

3. Instituto Boggio, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Gladstone Eustáquio de Lima Faria, Rua Alves Guimarães, 462, Sala 31, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 05410-000. E-mail: gladstonefaria@hotmail.com

Article received: July 24, 2019.

Article accepted: February 29, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter