Original Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Treatment of breast ptosis by placing subfascial silicone implants followed by inverted "T" mastopexy

Tratamento da ptose mamária através da colocação de implantes de silicone subfascial seguidos de mastopexia em "T" invertido

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The treatment of breast ptosis using mastopexy associated with the placement of silicone prosthesis in a single surgical procedure is a challenge for surgeons. There are several techniques described in the literature. This study aims to describe the placement of silicone breast implants in the subfascial plane, followed by an extensive anterior dissection of the pectoralis major muscle fascia, totally separating it from the rest of the breast parenchyma in the treatment of patients with breast ptosis. Moreover, analyze the aesthetic results of operated patients.

Methods: During the period from September 2017 to February 2019, 64 mastopexies with an inverted "T" scar were performed associated with silicone breast implants placed in the subfascial plane, bilaterally, textured high-profile round prostheses whose volumes ranged from 180ml to 380ml, in patients with breast ptosis.

Results: The average age was 34 years, ranging from 19 to 55 years. The postoperative follow-up time was 1 to 18 months. The main complications were: 3 cases (4.6%) of residual skin flaccidity in the 8-month follow-up; two cases (3.1%) of unsightly scars; one case (1.5%) of partial areola necrosis. There was no case of infection or seroma.

Conclusion: The technique of placing silicone breast implants in the subfascial plane, followed by an extensive anterior dissection of the pectoralis major muscle fascia, totally separating it from the rest of the breast parenchyma, was effective in the treatment of patients with breast ptosis.

Keywords: Breast; Prosthesis implant; Plastic surgery; Aesthetics; Atrophy.

RESUMO

Introdução: O tratamento da ptose mamária utilizando a mastopexia associada à inclusão

de prótese de silicone em tempo cirúrgico único é um desafio para os

cirurgiões. Existem várias técnicas descritas na literatura. O objetivo

deste estudo é descrever a colocação de implantes mamários de silicone em

plano subfascial, seguido de ampla dissecção anterior da fáscia do músculo

peitoral maior separando-a totalmente do restante do parênquima mamário no

tratamento de pacientes com ptose mamária; e analisar os resultados

estéticos dos pacientes operados.

Métodos: Durante o período de setembro de 2017 a fevereiro de 2019 foram realizadas

64 mastopexias com cicatriz em "T" invertido associadas à inclusão de

implantes mamários de silicone em plano subfascial, bilateralmente, próteses

redondas texturizadas de perfil alto cujos volumes variaram de 180ml a

380ml, em pacientes com ptose mamária.

Resultados: A média de idade foi de 34 anos, sendo que variou de 19 a 55 anos. O tempo

se seguimento pós-operatório foi de 1 a 18 meses. As principais complicações

foram: 3 casos (4,6%) de flacidez residual de pele no seguimento de 8 meses;

dois casos (3,1%) de cicatrizes inestéticas; um caso (1,5%) de necrose

parcial de aréola. Não houve nenhum caso de infecção ou seroma.

Conclusão: A técnica de colocação de implantes mamários de silicone em plano

subfascial, seguido de ampla dissecção anterior da fáscia do músculo

peitoral maior separando-a totalmente do restante do parênquima mamário foi

efetiva no tratamento de pacientes com ptose mamária.

Palavras-chave: Mama; Implante de prótese; Cirurgia plástica; Estética; Atrofia

INTRODUCTION

Breast ptosis is characterized by laxity and excess skin on the breasts, which can be associated, in most cases, with atrophy of the breast content or volume. The leading causes of breast ptosis are age, gravity, breastfeeding, and weight loss.

The surgery that corrects or treats breast ptosis is mastopexy. It aims to restore the breast’s shape1. When thinking about restoring the breast’s shape, this means not only repositioning them or bringing them to the “ideal” position. It also means remodeling it in its size and consistency, making it firmer. Still, in that same opportunity, an item that should not be overlooked is the nipple-areolar complex (NAC)2. The NAC must be located at the apex of the mammary “cone”. It must be repositioned and adequate in its size so that it is proportional to the size of the “new” breast, making it more harmonious and youthful. In other words, aspects that should be valued in mastopexy as a whole for the surgery’s success are breast location, shape, size, consistency, and NAC position.

The evaluation or quantification of breast ptosis in categories or types was initially carried out by the Frenchman Regnault in 19763. He proposed its classification taking into account the NAC position concerning the inframammary fold (IMF). Ptosis could be true (grade I, II, and III), partial ptosis, and pseudoptosis.

Most mastopexy techniques are derived from breast reduction techniques. In 1957, Arié4 described his mammoplasty technique, which was modified by Pitanguy, in 19605, adding the marking of point “A” (also called Pitanguy point). Silveira Neto, in 19766, described the super medial dermal flap with perforating vessels from the internal mammary artery.

In situations or cases where there is a significant breast volume loss, either by multiple pregnancies and consequent breastfeeding, or weight loss (in the case of morbidly obese ex-obese), silicone breast implants can be used. The first description in the literature was made by Gonzales-Ulloa, in 19607. Since then, many variants have been suggested, whether submuscular(8,9,10 )or subglandular11,12.

In 199913 and 200314, Graf et al. made the first description of the subfascial plan for breast augmentation surgery. Over these almost 20 years, the technique became popular(15-18 )and found its place as a good alternative for breast cosmetic and restorative surgery19,20. It is safe and is widely spread in our country 21. A recent study of breast fasciae (superficial and deep) 22 demonstrated the richness of details surrounding this organ anatomy and thus confirmed what had already been described in other regions of the human body; the concept of a bilaminar fascia system. These membranes join laterally and at the peripheries of anatomical structures, forming areas of adhesion. In these areas, there are vessels, nerves, and lymphatics. They are connected superior and inferior through thin ligaments.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study is to describe the placement of silicone breast implants in the subfascial plane, followed by an extensive anterior dissection of the pectoralis major muscle fascia, totally separating it from the rest of the breast parenchyma in the treatment of patients with breast ptosis. Moreover, analyze the aesthetic results of operated patients.

METHODS

During the period from September 2017 to February 2019, 64 mastopexies with an inverted “T” scar (as described by Pitanguy) were performed, associated with silicone breast implants placed in the subfascial plane, bilaterally, textured high-profile round prostheses whose volumes ranged from 180ml to 380ml in patients with breast ptosis. All patients came from a private clinic, operated by the same surgeon, under thoracic epidural anesthesia, following a thromboembolism prevention protocol, using prophylactic antibiotics, and using a 4.8 suction drain, as well as hospitalization for 24 hours.

Operative technique

The patient was operated on in the supine position, with a back tilt at 30o, abduction of the upper limbs at 90o, infiltration of saline solution (SS) with adrenaline in the proportion of 1: 250,000 in the marks previously performed in standing (orthostatic position).

1. Placement of the silicone implant

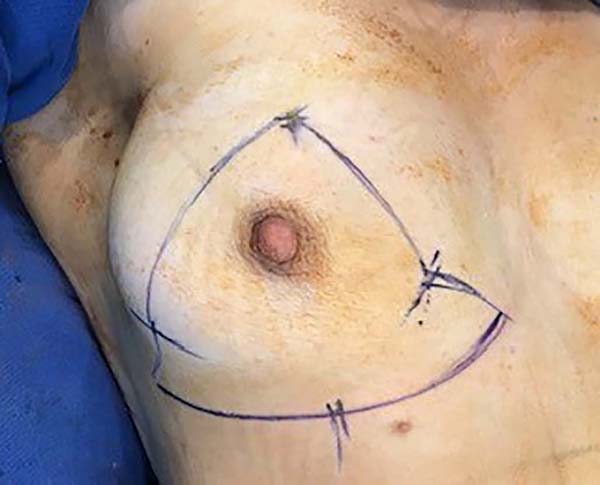

The surgery was started with skin and subcutaneous cell tissue (SSCT) incision in the inframammary fold (IMF), subfascial dissection to accommodate the previously chosen silicone breast implant. The subfascial pocket extended to the second intercostal space. Hemostasis of bleeding vessels was performed, irrigation of the prosthesis pocket with a solution of 100ml of SS with 1g of cefazolin and 80mg of gentamicin, using 50ml of the solution on each side (right and left), placement of a Mentor HP textured silicone implant and finally, closing or synthesis of the subfascial pocket with 3.0 monofilament thread in separate points (Figures 1 and 2).

2. Mastopexy

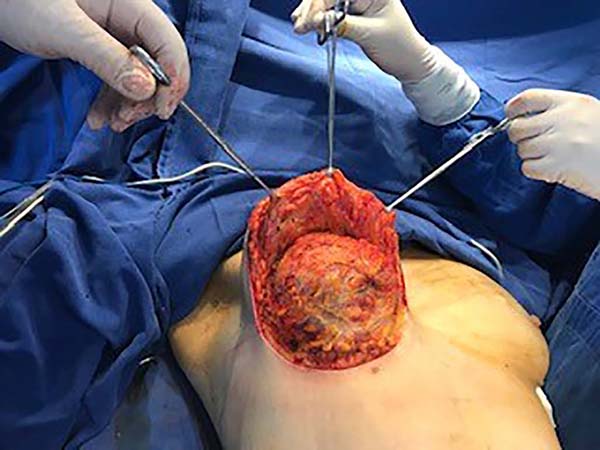

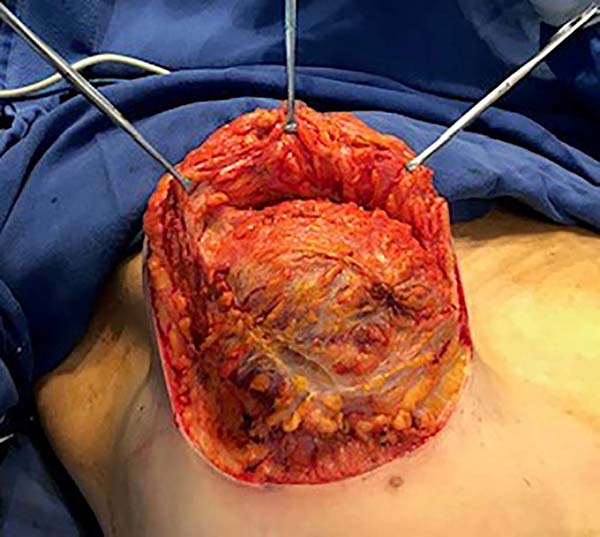

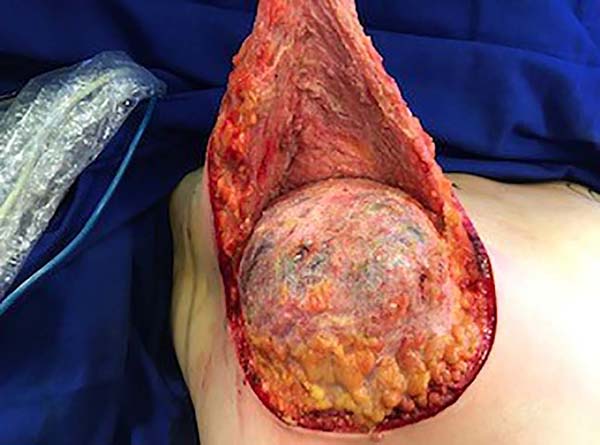

Then, the mastopexy itself started, with an incision in skin and SSCT over the marks made with methylene blue up to the pectoralis major muscle fascia, removing the breast tissue at the lower breast pole. When the aponeurosis is found, it is avoided to incise or damage it, keeping it intact, and then it is broadly dissected superiorly and laterally, freeing all breast tissue from the fascia, but keeping it adhered in its periphery to the pectoralis major muscle. Periareolar de-epithelialization (Schwartzmann maneuver) is then carried out between Pitanguy’s “ABC” points (Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8), followed by the NAC’s rise (Figure 9) through the Silveira Neto maneuver6 (medial dermal pedicle). The next step is the removal of the excess tissue, followed by approximation of the medial and lateral columns with nylon 3.0 thread in separate points, “assembling” the breast (Figures 10 and 11), placing a suction drain, subdermal suture with thread monofilament 4.0 in separate stitches and intradermal suture with 5.0 monofilament thread (Figure 12).

RESULTS

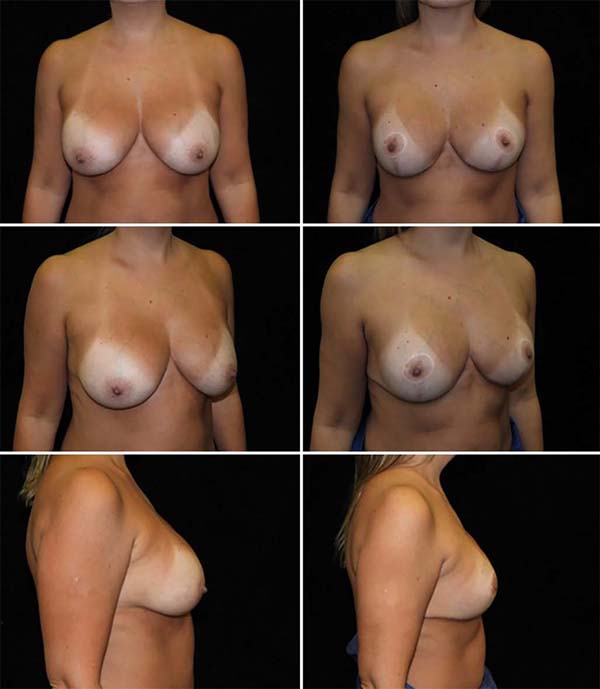

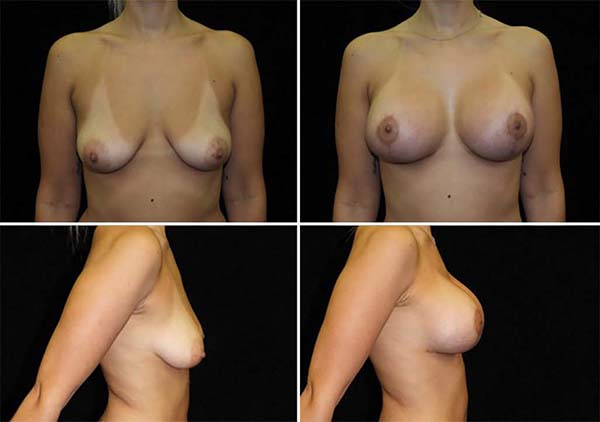

The average age of the 64 patients included in this study was 34 years, ranging from 19 to 55 years. Forty patients had grade 2 ptosis from the Regnault Classification, and twenty-four had grade 3 ptosis. The postoperative follow-up time was from 1 to 18 months, with 41 patients having a follow-up longer than six months (Figures 13 and 14) and 23 with fewer than six months.

The main complications were: 3 cases (4.6%) of residual skin flaccidity after eight months; two cases (3.1%) of unsightly scars (one hyperchromic and one hypertrophic); one case (1.5%) of partial NAC necrosis followed by partial suture dehiscence (Table 1). No case of infection or seroma. The patient who presented necrosis of 75% of NAC was one of the cases of grade 3 ptosis and smoker.

DISCUSSION

The option for mastopexy alone without introducing a silicone breast implant often does not bring total aesthetic satisfaction to the patient and the surgeon23. There are complaints in the late postoperative period of lower upper breast pole projection and breast consistency loss. In search of more effective results, surgeons opted for mastopexy with a single-time prosthesis7. The advantages would be many: better shape, projection, symmetry, adequate positioning of the NAC, and, if necessary, increased volume23.

The main benefit of locating the implant in the retroglandular plane is that it is less painful in the immediate postoperative period than the retromuscular plane. It allows for a more uniform distribution of the breast parenchyma on the silicone implant, leaving the breast more harmonious. The disadvantages would be the insufficient coverage of the implant, leaving the prosthesis more exposed, and the chance of flaccidity and pseudoptosis in the late postoperative period. With that in mind, some surgeons use the retromuscular plane8,9, which in addition to being more painful, brings the risk in the late postoperative period of glandular ptosis on the muscle and the implant, determining the aspect of “waterfall” (waterfall deformity).

The use of the fascia of the pectoralis major muscle as an option to cover the implant and its advantages over both retromuscular and retroglandular techniques became popular due to Graf et al. ‘s description in 199913 and 200314. This plan was chosen based on this premise for the location and positioning of silicone implants in this study.

Some other aspects differentiate this study, and they are: the implant placement is the first important step of the surgery, and the access route is through the IMF; there is an extensive dissection of the fascia, on its anterior face completely separating it from the rest of the breast. So, what are the intentions of these tactics? When opting for this silicone implantation initially, the idea is to avoid the exposure for an extended period, as it is a fast and safe procedure, bringing less risk of contamination. Some authors implant the silicone at the time of breast assembly23, exposing the prosthesis to the external environment for much longer. The access route through the IMF has lower capsular contracture rates than the areolar route18, probably due to implant contamination by bacteria from the mammary ducts normal flora; the areolar approach is the option of other authors12. The wide disconnection of the fascia anterior face, isolating the prosthesis/fascia (CPF) “set” from the rest of the breast (parenchyma), be it glandular and/or fatty, allows technical ease to assemble the breast, approaching the pillars and performing the maneuvers6 needed to reposition the NAC, for example. The breast parenchyma distribution over the CPF is done homogeneously, without exposure of the silicone (previously implanted in the subfascial plane) and, with practicality and range of movements, as there is a disconnection between the parenchyma and the deep fixation tissues (fascia) of the breast. It should be noted, however, that the fascia obviously remains attached to the pectoralis major muscle throughout its periphery, except for the 3 to 4 cm where it was incised to place the silicone, so it is on the periphery of anatomical structures that adhesion zones are formed, where are vessels, nerves and lymphatics; and they interconnect superior and inferior through thin ligaments22.

Concerning complications, the values were similar to those in the literature21,23. However, this study is concise compared to others23. The fact that there was no case of capsular contracture is perhaps not due to the subfascial technique itself, but due to the short period (18 months), especially in cases that were operated on less than six months ago. The complications observed here (one case of partial necrosis of the NAC, unsightly scars, and pseudoptosis) refer to the immediate and recent postoperative period. It should be noted that the case of NAC necrosis was in a smoking patient. The study’s continuity is necessary to obtain more practical and real data in relation, for example, to the capsular contracture index, through a more extensive sample, and, mainly, a longer time for analysis and comparison with the literature.

Like other authors13-17, some details could be observed concerning the subfascial plane. They are implant stability, peripheral protection of the silicone prosthesis making its edges less visible and less palpable, little bleeding during dissection, little pain postoperative, less postoperative edema, as there is the preservation of the lymphatics, as described13,14,22 and, consequently, easy recovery and faster return to daily activities.

CONCLUSION

The study demonstrated that the technique of placing silicone breast implants in the subfascial plane, followed by an extensive anterior dissection of the pectoralis major muscle fascia, completely separating it from the rest of the breast parenchyma, was effective in the treatment of patients with breast ptosis.

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

Special acknowlegments to Mr. Egídio for his collaboration during the reviews.

REFERENCES

1. Spear SL, Kassan M, Little JW. Guidelines in concentric mastopexy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990 Jun;85(6):961-6.

2. Castro CC, Coelho RF, Cintra HP. The value of non-prefixed markung in reduction mammoplasty. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1984;8(4):237-41.

3. Regnault PCI. Reduction mammplasty by B technique. In: Goldwyn RM, ed. Plastic and Reconstrutive Surgery of the Breast. Boston: Little Brown; 1976. p. 269-83.

4. Arié G. Una nueva técnica de mastoplastia. Rev Latinoam Cir Plast. 1957;3(1):23-31.

5. Pitanguy, I. Breast hypetrophy. In: Wallace AB, ed. Transactions of the International Society of Plastic Surgeons, Second Congress. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone; 1960. p. 509.

6. Silveira Neto E. Mastoplastia redutora setorial com pedículo areolar interno. In: Anais do XIII Congresso Brasileiro de Cirurgia Plástica e I Congresso Brasileiro de Cirurgia Estética; Abr 1976; Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. Porto Alegre (RS): SBCP; 1976.

7. Gonzales-Ulloa M. Correction of hypotrophy of the breast by means of exogenous material. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1960 Jan;25:15-26.

8. Daniel MJB. Inclusão de prótese de mama em duplo espaço. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2005;20(2):82-7.

9. Chiquetti A, Silva ABD. Tratamento das ptoses mamárias com implantes submusculares e pontos de fixação do tecido mamário ao muscular: aspectos técnicos e avaliação de resultado. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2018;33(3):317-23.

10. Khan UD. Muscle-spliting, subglandular, and partial submuscular augmentation mamoplasties: a 12-year retrospective analysis of 2026 primary cases. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2013;37(2):290-302.

11. Daher JC, Amaral JDLG, Pedroso DB, Cintra Junior R, Borgatto MS. Mastopexia associada a implante de silicone submuscular ou subglandular: sistematização das escolhas e dificuldades. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012 Abr/Jun;27(2):294-300.

12. Carramaschi FR, Tanaka MP. Mastopexia associada à inclusão de prótese mamária. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2003;18(1):26-36.

13. Graf RM, Bernardes A, Auersvald A, Damasio RCC. Subfascial endoscopic transaxillary augmentation mammaplasty. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 1999;14(2):45-54.

14. Graf RM, Bernardes A, Rippel R, Araujo LR, Damasio RC, Auersvald A. Subfascial breast implant: a new procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(2):904-8.

15. Hunstad JP, Webb LS. Subfascial breast augmentation: a comprehensive experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010 Jun;34(3):365-73.

16. Tijerina VN, Saenz RA, Garcia-Guerrero J. Experience of 1000 cases on subfascial breast augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010 Fev;34(1):16-22.

17. Goes JCS, Munhoz AM, Gemperli R. The subfascial approach to primary and secondary breast augmentation with autologus grafting form-stable implants. Clin Plast Surg. 2015 Out;42(4):551-64.

18. Benito-Ruiz J, Manzano ML, Salvador-Miranda L. Five-year outcomes of breast augmentation with form stables implants: periareolar vs transaxillary. Aesthetic Surg J. 2017 Jan;37(1):46-56.

19. Jinde L, Jianliang S, Xiaoping C, Xiaoyan T, Jiaqing L, Qun M, et al. Anatomy and clinical significance os pectoral fascia. Plast Recontr Surg. 2006 Dez;118(7):1557-60.

20. Egeberg A, Sorensen JA. The impact of breast implant location on the risk of capsular contraction. Ann Plast Surg. 2016 Ago;77(2):255-9.

21. Abramo AC, Scartozzoni M, Lucena TW, Sgarbi RG. High- and extra- high-profile round implants in breast augmentation: guidelines to prevent rippling and implant edge visibility. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018 Nov;43(2):305-12.

22. Rehnke RD, Groening RM, Van Buskirk ER, Clarke JM. Anatomy of the superficial fascia system of the breast: a comprehensive theory of breast fascial anatomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Nov;142(5):1135-44.

23. Wada A, Millan LS, Galafrio ST, Gemperli R, Ferreira MC. Tratamento da ptose mamária e hipomastia utilizando a técnica de mamoplastia com pedículo súpero medial e implante mamário. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(4):576-83.

1. Faculdade Evangélica de Medicina,

Department of Surgery, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Lincoln Graça Neto Rua Ângelo Sampaio, 2029, Batel,Curitiba, PR, Brazil. Zip Code: 80420-160 E-mail: lgracaneto@hotmail.com

Article received: May 13, 2019.

Article accepted: July 15, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter