Case Report - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Surgical treatment of infantile nasal and labial hemangioma in the involuted phase: a case report

Tratamento cirúrgico de hemangioma infantil nasal e labial na fase involuída: relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor and the most frequent benign neoplasm in childhood, with the highest incidence in females and the white population. Almost 60% of cases occur in the head and neck, and active treatment during the proliferative phase is the most frequently indicated, due to possible functional problems and disfiguring potential. We report a case of a patient with involute infantile hemangioma of the nasal tip and upper lip, treated expectantly during childhood, submitted to residual deformity correction with rhinoplasty techniques, associated with zetaplasty and upper lip grafting with good results and patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Hemangioma; Rhinoplasty; Lip; Nasal diseases; Nose.

RESUMO

Hemangioma infantil (HI) é o tumor vascular mais comum e a neoplasia benigna mais frequente da infância, com maior incidência no sexo feminino e na população branca. Quase 60% dos casos ocorrem em cabeça e pescoço, sendo o tratamento ativo durante a fase proliferativa mais frequentemente indicado, em decorrência dos possíveis problemas funcionais e do potencial desfigurante. Relatamos um caso de paciente com hemangioma infantil involuído de ponta nasal e lábio superior, tratado de forma expectante durante a infância, submetida à correção da deformidade residual com técnicas de rinoplastia, associado à zetaplastia e lipoenxertia do lábio superior com bom resultado e satisfação do paciente.

Palavras-chave: Hemangioma; Rinoplastia; Lábio; Doenças nasais; Nariz

INTRODUCTION

Infantile hemangioma (IMH) is the most common benign vascular tumor in childhood, with a higher incidence in females and the white population. Almost 60% of cases occur in the head and neck, and those located on the face are more associated with psychosocial, aesthetic and functional disorders1-2.

The lesion varies clinically according to its evolution throughout the child’s growth, which has a natural history divided into 3 phases: the initial growth phase, called proliferative; the spontaneous or involuting regression phase and the final or involuted equilibrium phase1.

When considering central hemangiomas of the face, and especially nasal hemangiomas, active treatment during the proliferative phase becomes more frequently indicated, due to the possible functional problems and the disfiguring potential that such lesions can present2,3.

Some studies also indicate that the rate of spontaneous resolution of nasal hemangiomas is lower, even after the end of the proliferative phase. The presence of fibrous fat deposits and excess skin can cause contour deformation and contribute to the unsatisfactory outcome often seen in untreated lesions. Thus, cases not treated with propranolol or not operated in childhood often require correction in the adult phase, due to aesthetic and/or functional discomfort3-6.

OBJECTIVE

Report a case of infantile hemangioma with nasal tip, columella and upper lip, treated surgically in the involuted phase.

CASE REPORT

A 28-year-old female patient reported the presence of a reddish lesion on the nasal tip, columella, upper lip filter, and part of the vermilion, which appeared in the first days of life. The lesion was treated expectantly, without the use of medications, evolving with spontaneous size reduction, from 3 years of age. Despite this, the patient maintained increased volume in the nasal tip and retraction of the upper lip, with whistling deformity (Figures 1 and 2).

Surgical procedures

Rhinoplasty

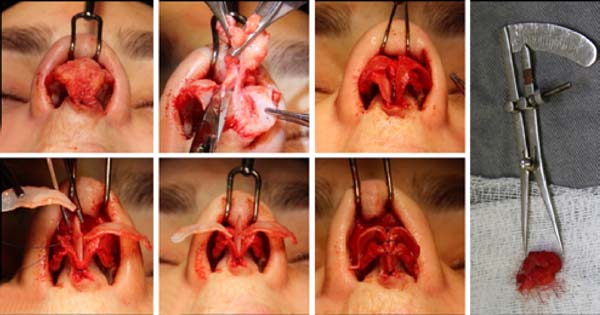

Open rhinoplasty, with transcolumellar and marginal access, is performed to resect the excess soft tissue and improve the definition of the nasal tip.

The following changes were identified concerning the normal anatomy of the nose: the presence of anomalous fibrofatty tissue in the columella and nasal tip, compatible with the involuted hemangioma (measuring 1.8 cm) and a discontinuity of the alar cartilage in the domus region on the right, with narrow and fragile medial crosses. After resection of the excess fibrofatty tissue, we opted for amputation and reinsertion of the lateral crosses with the construction of a neodomus, equalizing the forces between the sides and avoiding possible asymmetries (Figure 3). In order to acquire a good projection and definition of the nasal tip, a columellar strut was used, fixed to the medial crosses and transdomal points were performed (Figure 3).

It is essential to highlight that there were no technical difficulties related to bleeding or dissection of the planes, besides the usual ones found in a rhinoplasty.

Labiaplasty

In the upper lip, mucosal zetaplasty was chosen, allowing the wet vermilion to progress and the retraction to improve. Due to the persistence of lack of volume and projection in the region, 2ml fat grafting was associated with the resolution of the whistling deformity (Figure 4).

The patient was followed up in the postoperative period with satisfactory evolution, accommodation of skin on the nose, and improvement of lip deformity (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Due to their central location on the face and great aesthetic importance, nasal hemangiomas are uncomfortable injuries for patients and family members. They can course with local complications, functional impairment, deformities and impact on psychosocial development1-2.

Besides the expectant behavior, pharmacological and surgical interventions and laser use are the current treatment options. Propranolol represents the first line for IH due to its high efficacy, and safety7. Surgery maintains its role in refractory cases, in those with local complications, with functional impairment and for sequelae after hemangioma regression.

The ideal moment for surgical indication is still controversial in the literature. The benefits of early intervention, even for limited lesions, are to reduce the damage caused by the proliferation of hemangiomas, avoiding damage to the growth of nasal cartilages8.However, nasal reconstruction in young children is challenging, and the potential risk of iatrogenic deformity, nasal skeletal growth disorders, or excessive scarring should be considered5,8.

Authors like Giugliano et al., in 20189, prefer to perform the surgery in the involuted phase, considering that the anatomical structures are better defined and the size of the lesion may have reduced, making the reconstruction technically easier and with a consequent better result. In their series, there was no change in growth, but the separation of different structural elements of nasal cartilages, requiring adequate repositioning of the alar complex. These findings are similar to the experience reported by Waner et al. in 20086 and Hochman et al. in 200510, noting that the destruction of the cartilage is unusual.

In the present case, we also observed bleeding similar to that of other rhinoplasties, consistent with the literature. In cases of isolated involvement of the nasal tip, due to deep and involuted hemangioma (without skin involvement), there is an indication for open rhinoplasty (McCarthy et al., In 20025) and excess skin may be resected. In the case above, we chose not to resect the excess skin, as we believe that, with the improvement of the definition and projection of the tip, the skin presents suitable accommodation and satisfactory aesthetic results.

On the other hand, an open rhinoplasty will not always be the surgical solution for involuted cases. In cases of skin involvement in the subunit of the nasal tip or contiguity with other subunits, a frontal flap or another regional flap is indicated to provide adequate reconstruction. When other subunits are affected, a direct excision can also be performed5.

COLLABORATIONS

|

MM |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing. |

|

RCL |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation. |

|

LCI |

Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing. |

|

RG |

Supervision, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Hiraki PY, Goldenberg DC. Diagnóstico e tratamento do hemangioma infantil. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2010;25(2):388-97.

2. Boye E, Jinnin M, Olsen BR. Infantile hemangioma: challenges, new insights, and therapeutic promise. J Craniofac Surg. 2009 Mar;20(Suppl 1):678-84.

3. Bruckner AL, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:477-93.

4. Frieden IJ, Eichenfield LF, Esterly NB, Geronemous R, Mallory SB. Guidelines of care for hemangiomas of infancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997 Oct;37(4):631-7.

5. McCarthy JG, Borud LJ, Schreiber JS. Hemangiomas of the nasal tip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002 Jan;109(1):31-40.

6. Waner M, Kastenbaum J, Scherer K. Hemangiomas of the nose. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2008;10(5):329-34.

7. Leaute-Labreze C. Infantile hemangiomas: the revolution of betablockers. Rev Prat. 2014 Dec;64(10):1421-8.

8. Cho S, Lee SY, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Treatment of Cyrano angioma with pulsed dye laser. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:670-2.

9. Giugliano C, Reculé F, Guler K, Gantz JT, Hasbún T. Persistent nasal infantile hemangioma: a surgical treatment algorithm. J Craniofac Surg. 2018 Sep;29(6):1509-13.

10. Hochman M, Mascareno A. Management of nasal hemangiomas. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2005;7:295-300.

1. Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da USP, Disciplina de Cirurgia Plástica

e Queimaduras, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Rodolfo Costa Lobato, Rua da Consolação, 3741, 11º andar, Cerqueira Cesar, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 01416-907. E-mail: rodolfolobato49@yahoo.com.br

Article received: April 04, 2019.

Article accepted: June 22, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter