Original Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Comparison of surgical techniques for prominent ear correction: Mustardé versus Converse

Comparação de técnicas cirúrgicas de correção de orelhas proeminentes: Mustardé versus Converse

ABSTRACT

Introduction: prominent ears, popularly called "flappy ears," represent the most common congenital deformity of the external ear, affecting approximately 5% of the population.

Methods: Primary, prospective and intervention study comparing the results of patients undergoing the surgical procedure to correct prominent ears using the Converse and the Mustardé techniques, performed at the Plastic Surgery Service of the Hospital das Clínicas, Federal University of Pernambuco (HC) -UFPE).

Results: Twenty patients were evaluated, 10 with the Converse technique, and 10 with the Mustardé technique, from June 2016 to December 2017. Both groups showed a decrease in auricular mastoid distances at the end of the observation period, ranging from 6.67 to 14.6 mm, depending on the surgical technique and the evaluation point, but without statistical significance. Regarding the average auricular mastoid distances at the end of the observation period, a difference of a maximum of 6.3 mm was observed between the evaluated groups, but without statistical significance. Regarding the symmetry of the ears within the same group, the maximum mean level of asymmetry in the Mustardé and Converse groups was 0.9 mm and 0.5 mm, respectively. However, the percentage of loss of correction of the measures obtained surgically during the observation period in both groups ranged between 15 and 19%, without statistical significance. Regarding complications, there was 1 (10%) case of hematoma in the Mustardé group.

Conclusion: Converse and Mustardé techniques did not show statistical differences in the results.

Keywords: Auricular Cartilage; Plastic surgery; Auricle; Outer ear; Otopathies.

RESUMO

Introdução: As orelhas proeminentes, popularmente chamadas de "orelhas em abano", representam a deformidade congênita mais comum da orelha externa, atingindo cerca de 5% da população.

Métodos: Estudo primário, prospectivo e de intervenção comparando os resultados de pacientes submetidos ao procedimento cirúrgico de correção de orelhas proeminentes por meio da técnica de Converse e de Mustardé, realizado no Serviço de Cirurgia Plástica do Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (HC-UFPE).

Resultados: Foram avaliados 20 pacientes, 10 por meio da técnica de Converse e 10 por meio de Mustardé, no período de junho de 2016 a dezembro de 2017. Ambos os grupos mostraram diminuição das distâncias mastoideas auriculares ao final do período de observação, variando de 6.67 a 14.6 mm, a depender da técnica cirúrgica e do ponto de avaliação, mas sem significância estatística. Quanto às distâncias mastoideas auriculares médias ao final do período de observação, observou-se diferença de no máximo 6.3mm entre os grupos avaliados, mas sem significância estatística. Em relação a simetria das orelhas dentro do mesmo grupo, o nível máximo de assimetria média nos grupos Mustardé e Converse foi de respectivamente 0.9mm e 0.5mm. A porcentagem da perda de correção das medidas obtidas cirurgicamente ao longo do período de observação em ambos os grupos variaram de 15-19%, no entanto, sem significância estatística. No que se refere as complicações, houve 1 (10%) caso de hematoma no grupo Mustardé.

Conclusão: As técnicas de Converse e Mustardé demostraram não ter diferença estatística nos resultados.

Palavras-chave: Cartilagem articular; Cirurgia plástica; Orelha externa; Pavilhão auricular; Otopatias

INTRODUCTION

Prominent ears, popularly called “flappy ears,” represent the most common congenital deformity of the outer ear, affecting approximately 5% of the population1. Both sexes are affected in the same proportion, and in approximately 60% of cases, this deformity can be diagnosed at birth, which is most evident in the first years of life2,3.

People with prominent ears have facial and aesthetic harmony problems, which can lead to psychic disorders related to social interaction, especially during childhood and adolescence3,4,5. The outer ear reaches 85% of its final size around three years of age, reaching adult size around 6 to 7 years6. Therefore, the ideal age for surgical correction would be between 4 and 6 years, since it also coincides with the beginning of the individual’s school/social life4,7.

The most common cause of ear prominence is erasure or absence of the antihelix, present in two-thirds of cases, resulting in lateral projection of the helix6. However, other changes may also be present in combination or not, namely: hypertrophy of the shell, increase in the cephaloconcal angle (> 90°) and protrusion of the lobe1,8.

Otoplasty techniques have been developed using different antihelix treatment methods, such as sutures, repositioning, incision and excision of cartilage3,9. In general, the antihelix treatment can be divided into two categories: incisional/abrasive and cartilage saving10. The first aesthetic otoplasties were described by Ely, in 188111 and Luckett, in 191012, being examples of incisional techniques13,14.

After several reports of techniques published in the literature, Converse, in 196315,16, associated the incision of cartilage with sutures in order to produce a more natural result to the antihelix and avoiding failures common to previous techniques10. In 1963, Mustardé17 was the first surgeon to describe the recreation of the antihelix fold with only multiple horizontal sutures, thus being a technique classified as cartilage-sparing13.

Since then, several studies published in the literature have evaluated the postoperative results obtained with different surgical techniques. However, no published studies are comparing the results of different surgical techniques for the treatment of prominent ears.

OBJECTIVE

This study proposes to make a comparison between two surgical techniques for antihelix treatment used in the correction of prominent ears: The Converse and Mustardé techniques, evaluating the surgical results, and observing if there is superiority between them.

METHODS

Primary, prospective and intervention study comparing the results of patients undergoing the surgical procedure to correct prominent ears using the Converse technique and that of Mustardé, performed at the Plastic Surgery Service of the Hospital das Clínicas of the Federal University of Pernambuco (HC -UFPE).

Patients were randomly selected into two different groups of surgical techniques to correct the antihelix, the Mustardé technique, and the Converse technique. Patients who spontaneously sought service with the desire to correct prominent ears and who had absence or underdevelopment of the antihelix were included. Patients who had already undergone previous auricular surgical procedures, patients with congenital or acquired auricular deformities, smokers, patients with chronic systemic diseases, and users of chronic medications were excluded.

The imposed data were: sex, age, presence of erasure of anti-helix, shell hypertrophy, lobe protrusion, increased cephalocaudal angle, laterality, auricular mastoid distance in three sites of the ear external, complementary surgical treatment performed and complications.

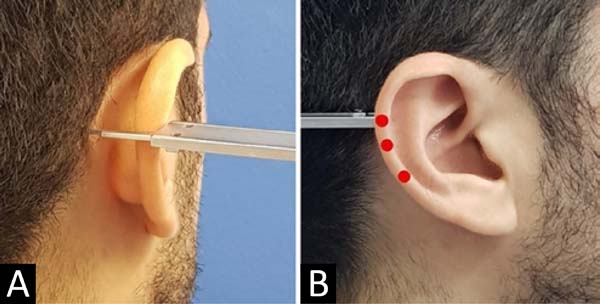

The auricular mastoid distances were measured from the mastoid region to the lateral edge of the helix, with the head in a neutral position, measured with the aid of an analog pachymeter in the upper, middle and lower regions, bilaterally, which correspond respectively to the bifurcation of the antihelix in upper and lower branches, the upper edge of the ear canal and the most caudal segment of the intertragic notch (Figure 1). The evaluation times were: preoperative, 1, 3, and 6 months postoperative, with the necessary photographic documentation.

Surgical technique

All patients underwent the surgical procedure under local anesthesia and propofol sedation. After removal of a retroauricular skin spindle, detachment of the skin with adequate exposure of the posterior region of the auricular cartilage, one of the following procedures is followed:

Mustardé technique

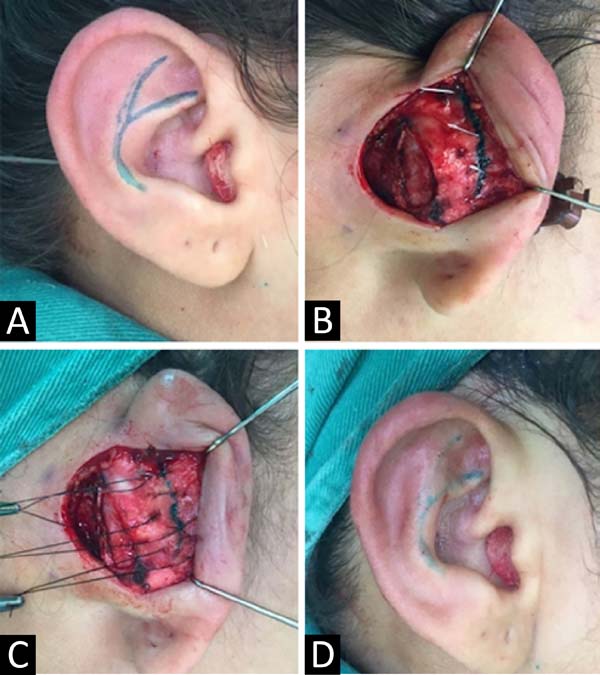

It is performed the bidigital anterior maneuver of the scapha with the thumb and forefinger, transfixed in 3 places along the antihelix, which was pronounced, with the help of a 0.45x13mm needle dyed in bright green to make the “tattoo” of the posterior face of the cartilage. Suture with 4-0 mononylon, about 1 cm laterally, the previous markings for the formation of a new antihelix (Figure 2).

Converse technique

It is performed the bidigital anterior maneuver of the scapha with the thumb and forefinger, and it is transfixed in 3 points along the antihelix, which was pronounced with the help of a 0.45x13 mm needle dyed in bright green to make the “tattoo” of the posterior cartilage. An incision is made with a scalpel blade 15, bilaterally, joining the previous markings. Subsequently, the internal/external edges are sutured with mono nylon 4-0 in 3 places to form a new antihelix (Figure 3).

After performing the surgical technique of each group, it is then followed for the other treatments: Furnas stitches and lobe repositioning, if necessary, and the skin is closed with 4-0 mono nylon.

The research followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, revised in 2000, and Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council. It was also submitted to the institution’s Ethics and Research Committee (CEP), being approved with CAAE 64223417.9.0000.5208 and Opinion 2,019,499. The data were grouped in a Microsoft Office Excel 2015 spreadsheet, analyzed by SPSS software version 2.0 R version 3.4.3.

The non-parametric statistical test used was Wilcoxon’s, considering a value of p <0.05.

RESULTS

Twenty patients were evaluated, 10 using the Converse technique and 10 using Mustardé, from June 2016 to December 2017. Males represented 30% of both groups, the mean age in the Converse and Mustardé group was 18.9 and 22.3 years, respectively. All patients in the study had erasure of the antihelix, increased cephaloconchal angle, and bilateral abnormalities. Conchal hypertrophy and lobe protrusion were present in 19 (95%) and 6 (30%) patients, respectively. The treatment of the concha using the Furnas technique and the treatment of the lobe was performed in all patients who presented these changes.

Both groups showed a decrease in auricular mastoid distances at the end of the observation period, ranging from 6.67 to 14.6 mm, depending on the surgical technique and the evaluation point, however, in comparison, there was no significant p-value between the group results Regarding the average auricular mastoid distances at the end of the observation period, a difference of a maximum of 6.3 mm was observed between the results obtained, but also with a negligible p-value (Table 1).

| Measurement locations |

Means | Significance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mustardé | Decrease | Converse | Decrease | p-valor | |||

| Evaluation time | Preoperative | 6 Months | Preoperative | 6 Months | |||

| Upper/right third | 29.60 | 15 | 14.60 | 29.10 | 15.27 | 13.83 | 0.726 |

| Upper/left third | 29.60 | 15.50 | 14.10 | 28.80 | 15.77 | 13.03 | 0.9523 |

| Middle/right third | 28.60 | 15.60 | 13 | 27.30 | 15.13 | 12.17 | 0.7648 |

| Middle/left third | 27.10 | 15.50 | 11.60 | 26.40 | 15.50 | 10.90 | 0.6232 |

| Lower/right third | 19.90 | 12.10 | 7.80 | 20.10 | 12.73 | 7.37 | 0.2931 |

| Lower/left third | 21.70 | 13 | 8.70 | 19.40 | 12.73 | 6.67 | 0.6808 |

Regarding the symmetry of the ears within the same group, the maximum mean level of asymmetry in the Mustardé and Converse groups was 0.9 mm and 0.5 mm, respectively (Table 2). When evaluating the percentage of loss of correction of the measures obtained surgically during the observation period, both groups ranged between 15-19%, however, in comparison with each other, there were no significant differences between the results (Table 3). Regarding complications, there was 1 (10%) case of hematoma in the Mustardé group.

| Measurement locations | Mustardé | Converse | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | Asymmetry | Left | Left | Asymmetry | |

| Upper third | 15 | 15.50 | 0.50 | 15.27 | 15.77 | 0.50 |

| Middle third | 15.60 | 15.50 | 0.10 | 15.13 | 15.50 | 0.37 |

| Lower third | 12.10 | 13 | 0.90 | 12.73 | 12.73 | 0 |

| Measurement locations | Means | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mustardé | Converse | p-value | |

| Upper/right third | 18% | 19% | 0.726 |

| Upper/left third | 19% | 18% | 0.9523 |

| Middle/right third | 16% | 17% | 0.7648 |

| Middle/left third | 17% | 17% | 0.6232 |

| Lower/right third | 15% | 15% | 0.2931 |

| Lower/left third | 16% | 15% | 0.6808 |

DISCUSSION

The Mustardé and Converse techniques described, respectively, in 1955 and 1963, have their uses spread throughout the world; however, like all surgical tactics, they present their positive and negative points. The Converse technique, considered incisional, has as a positive point the fact that the cartilaginous incision provides a loss of local resistance for the manufacture of the new antihelix, decreasing the tension in the suture, supposedly decreasing recurrence rates, however as a negative point, this incision can provide visible contour irregularities to the anti-helix6,18.

On the contrary, the Mustardé technique, considered cartilage-sparing, has the advantage of providing a smooth contour for the antihelix, on the other hand, due to the lack of weakening of the cartilage, there is supposed to be a tendency for the cartilage returns to its abnormal position, which can cause an increase in recurrence rates6,18.

In general, in order to achieve the best results, the following aspects described by McDowell, in 196819, must be observed and fulfilled: 1) the helix must be seen entirely behind the antihelix in the frontal view; 2) smooth and regular helix; 3) final scar must be located in the retroauricular groove and without distortion; 4) difference in measurements between the operated sides of a maximum of 3mm; and, 5) the distance from the helix to the mastoid, at the upper, middle and lower points, should vary between 10-12mm, 16-18mm and 20-22mm18 respectively.

It was observed that both groups reached all the above criteria during the observation period, except for the proposed distances, however, McDowell does not describe in his article how such measurements were determined, which hinders a reliable comparison9. However, the final measurements of the present study comply with that established by Adamson et al., in 199120, which determines an auricular mastoid distance from the upper-middle segment of the ear between 15 and 20 mm as aesthetically desirable20 (Table 4). When comparing the final averages of the auricular mastoid distances, between the two surgical techniques evaluated, there was a difference of 6.3 mm maximum between the results obtained, but with an unimportant p-value, that is, both techniques provided similar auricular positions (Table 1).

| Locais de mensuração | Médias | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grupo Mustardé | Grupo Converse | Adamson, 1991 | McDowell, 1968 | |

| Terço superior/direito | 15 | 15.27 | 15-20 | 10/dez |

| Terço superior/esquerdo | 15.50 | 15.77 | ||

| Terço médio/direito | 15.60 | 15.13 | 16-18 | |

| Terço médio/esquerdo | 15.50 | 15.50 | ||

| Terço inferior/direito | 12.10 | 12.73 | Não definido | 20-22 |

| Terço inferior/esquerdo | 13 | 12.73 | ||

Both groups showed a decrease in auricular mastoid distances at the end of the observation period ranging from 6.67 to 14.6 mm, very similar to that found in the literature, as the studies by Adamson et al., in 199120, Schneider and Side, in 201821 and Foda, in 199922, obtained average rates of auricular medialization, respectively, of 5.9 mm, 14 mm and 17 mm, depending on the place and time of the evaluation. As for the symmetry between the ears within the same surgical technique, the asymmetry varied from 0 to 0.9 mm, that is, both groups remained within the maximum of 3 mm recommended in the literature18,21 (Table 2). Despite being a subjective criterion, the surgical team and all patients were satisfied with the results obtained at the end of the observation period20 (Figures 4 and 5).

Regarding the percentages of loss of correction, these would vary from 15 to 19% in both groups, depending on the follow-up evaluated. These values are lower than those found in the literature, such as that of Foda, in 199922, in which the average was 32%; however, this one had a follow-up of 28.4 months, that is, we could observe a higher percentage in more extended monitoring period. Another point to highlight would be that the difference between the groups was a maximum of 1%, but with an unimportant p-value compared to each other, which suggests an equivalence of the rates of correction loss between the surgical techniques (Table 3).

As for complications, Elliott divides complications into early and late. The precocious ones would be a hematoma, infection, chondritis, pain, bleeding, itching, and skin necrosis. Late ones would be visible scarring, patient dissatisfaction, suture-related problems, and dysesthesias6. We observed only one case of hematoma in the Mustardé group; however, the literature shows complication rates ranging from 0% to 47.3%, that is, the index found in this research remained within the expected range23,24. The treatment was performed with simple outpatient drainage and a compressive dressing with adequate resolution of the case.

It is noteworthy that no studies were found in the literature comparing surgical techniques to reposition the antihelix using a standardized and objective measurement protocol. Another positive point, Tables 1 and 3, which show, respectively, the means of the final measurements of the points evaluated between the groups and the percentages of the means of recurrence, did not obtain the p-value at the 5% level with the test. Wilcoxon. In other words, the sample size did not influence the comparison of results between the Mustardé and Converse techniques. Furthermore, therefore, the sample size used in the research was sufficient to conclude that the lack of difference in the results between the treatments evaluated was not due to the number of participants, but to the similarity of the results of the techniques.

On the other hand, a possible bias in this study was the 6-month follow-up period, as there are studies with periods of up to 6.25 years9. That is, we could then experience higher rates of correction loss, complications, and even recurrence of prominent ears.

CONCLUSION

The Converse and Mustardé techniques showed no statistical difference in the results, when compared to each other.

REFERENCES

1. Rosique RG, Rosique MJF. Refinamento da técnica de Mustardé para tratamento de orelhas proeminentes. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(4):490-6.

2. Alencar EC, Lucena JRS, Carvalho Filho RAS, Oliveira KPF, Almeida CLA. Correção cirúrgica de orelhas proeminentes: associação da técnica de Furnas e Mustardé. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(3):439-45.

3. Hornos A. Correção de orelha de abano por técnica combinada: análise de resultados e alteração da qualidade de vida. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(3):406-15.

4. Toplu Y, Sapmaz E, Toplu SA, Deliktas H. Otoplasty: results of suturing and scoring techniques. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013 Jul;271(7):1885-9.

5. Bradbury ET, Hewison J, Timnons MJ. Psychological and social outcome of prominent ear correction in children. Br J Plast Surg. 1992 Feb/Mar;45(2):97-100.

6. Janis JE, Rohrich RJ, Gutowski KA. Otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(60e):60-72.

7. Haytoglu S, Haytoglu TG, Muluk NB, Kuran G, Arikan OK. Comparison of two incisionless otoplasty techniques for prominent ears in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015 Apr;79(4):504-10.

8. Jinguang Z, Leren H, Hongxing Z. Experience of correction of prominent ears. J Craniofac Surg. 2010 Sep;21(5):1578-80.

9. Calderoni DR, Motta MM, Kharmandayan P. Development and implementation of an anthropometric protocol to evaluate results of otoplasty. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2016;31(1):66-73.

10. Peterson RS, Friedman O. Current trends in otoplasty. Curr Opin Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16(4):352-8.

11. Ely et.al. An operation for prominence of the auricles. Arch Otolaryngol. 1881;10:97.

12. Luckett W. A new operation for prominent ears based on the anatomy of the deformity. Surg. Gynec. & Obst. 1910;10:635-7.

13. Nuara MJ, Mobley SR. Nuances of otoplasty: a comprehensive review of the past 20 years. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2006 May;14(2):89-102.

14. Nazarian R, Eshraghi AA. Otoplasty for the protruded ear. Semin Plast Surg. 2011 Nov;25(4):288-94.

15. Naumann A. Otoplasty - techniques, characteristics and risks. Curr Opin Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;6(1):1-14.

16. Converse JM, Wood-Smith D. Technical details in the surgical correction of the lop ear deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1963 Feb;31(2):118-28.

17. Mustardé JC. The correction of prominent ears using simple mattress sutures. Br J Plast Surg. 1963 Apr;16:170-8.

18. Gümus N, Yilmaz S. Otoplasty with an unusual cartilage scoring approach. J Blast Sure Hand Surg. 2016;50(1):19-24.

19. McDowell AJ. Goals in Otoplasty for Protruding Ears. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968 Jan;41(1):17-27.

20. Adamson PA, McGraw BL, Trooper GJ. Otoplasty: critical review of clinical results. Laryngoscope. 1991 Aug;101(8):883-8.

21. Schneider AL, Side DM. Cosmetic otoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2018 Feb;26(1):19-29.

22. Foda HMT. Otoplasty: a graduated approach. Aesth Last Surg. 1999;23:407-12.

23. Handler EB, Song T, Shih C. Complications of otoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013 Nov;21(4):653-62.

24. Maricevich JPR, Amorim NFG, Duprat R, Freitas F, Pitanguy I. Island technique for prominent ears: an update of the Ivo tangy clinic experience. Aesthet Surg J. 2011 Aug;31(6):622-33.

1. Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, Brasil.

Corresponding author: Marcel Fernando Miranda Batista Lima, Rua Barão de Itamaracá, nº78 - apto 1203 - Espinheiro, Recife, PE, Brazil. Zip Code: 52020-070 E-mail: marcelflima@hotmail.com

Article received: September 30, 2019.

Article accepted: February 22, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter