Special Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Protocols and complications in the reconstruction of major scalp defects

Condutas e intercorrências na reconstrução de grandes defeitos do couro cabeludo

ABSTRACT

Introduction: This study aimed to analyze the protocols and complications in four unusual cases of large and complex scalp defects, in which conventional, non-microsurgical flaps were used.

Methods: This was a critical and retrospective analysis of four cases. Three immunosuppressed patients had squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) (one underwent liver transplant, one underwent renal transplant, and one had rheumatoid arthritis). The other patient had sequelae of head trauma and multiple neurosurgeries using self-polymerizing acrylic, followed by osteomyelitis and fistula.

Results: The cases of large carcinoma were reconstructed with rotation large scalp flaps. Two of them had epidermolysis/necrosis in a small distal portion of the flaps, which were treated, with excellent aesthetic results. The case of sequelae of trauma was reconstructed with expanded advancement scalp flap over cranioplasty using ribs. Despite the extrusion of one osteosynthesis, the patient healed without recurrence of the fistula, with na excellent aesthetic result.

Conclusion: The analysis of these complex and unusual cases indicates that temporal pedicles are preferred in the planning of flaps for the conventional reconstruction of large scalp defects. The treatment employed for the possible epidermolyses and distal necroses in these flaps led to satisfying aesthetic and functional results.

Keywords: Scalp; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Head and neck neoplasms; Penetrating head trauma; Organ transplantation.

RESUMO

Introdução: Estudar as condutas e as complicações em quatro casos infrequentes de grandes e complexas deformidades do couro cabeludo, em que retalhos convencionais, não microcirúrgicos, foram empregados.

Métodos: Análise crítica e retrospectiva de três casos de carcinomas espinocelulares (CEC) em pacientes imunossuprimidos (transplantado renal, hepático e paciente com artrite reumatoide) e um caso de sequela de trauma cranioencefálico, decorrente de múltiplas neurocirurgias com emprego de acrílico autopolimerizável, seguido de osteomielite e fístula.

Resultados: Os casos de extensos carcinomas, foram reconstruídos com a rotação de grandes retalhos de couro cabeludo, havendo em dois deles epidermólise/necrose em pequena porção distal dos retalhos, que foram tratadas com excelente resultado estético. O caso sequela de trauma, foi reconstruído com retalho expandido de couro cabeludo, avançado sobre cranioplastia com costelas, que apesar da extrusão de uma osteossíntese, cicatrizou sem recidiva da fístula com excelente resultado estético.

Conclusão: A análise destes casos complexos e invulgares, indica preferencialmente os pedículos temporais no planejamento de retalhos para a reconstrução convencional de grandes defeitos do couro cabeludo. As possíveis epidermólises e necroses distais nestes retalhos, tratadas da forma apresentada, levaram a gratificantes resultados estéticos e funcionais.

Palavras-chave: Couro cabeludo; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Neoplasias de cabeça e pescoço; Traumatismos cranianos penetrantes; Transplante de órgãos

INTRODUCTION

The outer table of the calvarium receives nutrition through the periosteum. Large scalp defects owing to trauma or neoplasms can endanger the vitality of the bones of the neurocranium, dura mater, and underlying brain. The loose connective tissue between aponeurotic galea/epicranium muscle and periosteum favors intracranial metastases, thrombi, and infections1.

Large scalp defects are a major challenge for reconstruction, and in the absence of periosteum, these impair the use of skin grafts. Decortication of the outer table for skin grafting of the diploe provides aesthetically poor results, leading to fragility and susceptibility to malignancy. Romero et al., in 20182, published an algorithm recommending microsurgery for defects larger than 5 cm. Although vascular microsurgery provides the best results in the repair of large scalp defects3, it requires adequate team and resources. Souza, in 20124, used local flaps and emphasized the importance of superficial temporal vessels in maintaining the viability of these flaps.

CASE REPORTS

CASE 1

A 69-year-old male patient with hypertension and diabetes underwent kidney transplant 17 years ago and regularly uses immunosuppressants. He had actinic keratoses on the face, scalp, and limbs, which were treated with cryotherapy and fluorouracil. In 2015, he had large moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with muscle invasion in the dorsum of the nose and was treated by excision and coverage using midline forehead flap. He had multiple and recurrent moderately differentiated multifocal SCC in the parietal regions (Figure 1).

CASE 2

A 68-year-old male, white patient with diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis regularly uses corticosteroids and methotrexate. He had multiple actinic keratoses on the bald scalp and was initially treated with cryotherapy. After 4 years, he returned with a recent, rapid-growth, infiltrate, vegetative, painful, ulcerated lesion in the frontoparietal region of the scalp measuring 4.5 x 4.0 x 1.5 cm. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated, ulcerated SCC extending up to the hypodermis (Figure 2).

CASE 3

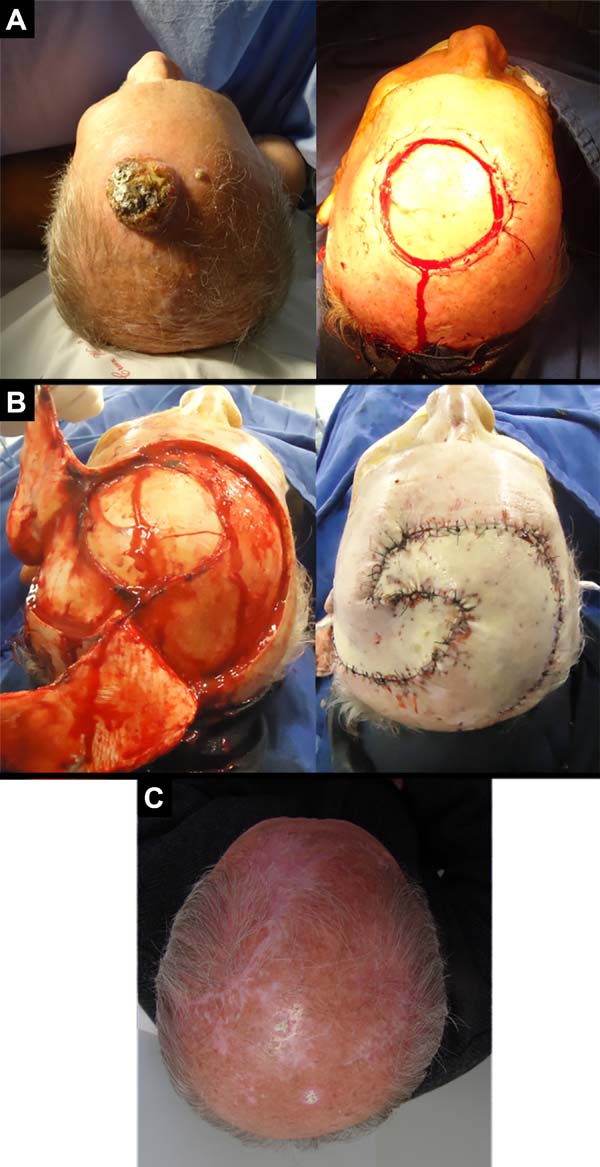

A 68-year-old male patient who underwent a liver transplant nine years ago and continuously uses immunosuppressants. He had a large vegetative lesion in the left parieto-occipital region. A biopsy revealed exophytic SCC (Figure 3).

CASE 4

An adult male patient who was struck with an ax seven years ago suffered head trauma. He was operated four times at Neurosurgery Services. For more than once, cranioplasty was performed with self-polymerizing acrylic, followed by subsequent infection and frontoparietal osteomyelitis, requiring the removal of the implant and new bone debridement (Figure 4).

At another service, he received partial skin graft placed directly on the remaining dura mater and the presumably performed galeal flap. Initial examinations revealed a frontoparietal defect, subdural clamps, and a clinically significant fistula draining serous material over the brain mass precariously protected by the graft. He had convulsive episodes after suffering minor trauma in the graft region during his work as a car mechanic.

DISCUSSION

The low elasticity, thickness of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, and presence of a thick aponeurotic galea on a convex surface make the reconstruction of large scalp defects a challenging task. Abundant anastomoses between the temporal, supraorbital, supratrochlear, posterior auricular and occipital vessels usually allow scalp flaps with only a small pedicle to survive and large flaps to recover without complications5,6.

Most published cases of SCC have reported occurrence in the head and neck, with 8.3%–25.2% lesions occurring in the scalp. The current large numbers of living patients who underwent transplantation require more attention since immunosuppressants contribute to the formation of skin neoplasms.

The clinical recommendation for the margin of excision of SCC is 4 mm for low-risk patients and 6 mm for high-risk patients7. We use about 10 mm of margin based on the pathology, frequently removing the periosteum.

In case 1, local relapses and coalescence of premalignant lesions required a large excision. Although the large defect (16 x 16 cm) indicated the need for a microsurgical free flap, the chronic use of immunosuppressants, diabetes, and hypertension increases the risk of compromising the kidney transplanted 17 years ago in a longer surgery. We used two temporal-parietal-occipital rotation flaps for the reconstruction. The first, with a pedicle in the right temporal region, was rotated to cover the earliest portion of the defect. The second, lower and longer, with pedicle in the left temporal region, was rotated to occlude the posterior portion. The secondary occipital defect, with intact periosteum, received an inguinal total skin graft. In the postoperative period, epidermolysis and superficial necrosis occurred on the distal margin of the first flap. They were treated by debridement with hyaluronidase and outpatient cleaning, followed by dressings with Rifamycin and, finally, by colloidal occlusive dressings, showing excellent results.

Chronic use of methotrexate in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis causes immunosuppression (case 2). After excision of the lesion, two randomized flaps were used: one larger and longer on the right with occipital pedicle, and one smaller on the left with temporal pedicle.

Distal suffering occurred in the flap on the right, leading to bone exposure and gap. With local anesthesia, a small flap of adjacent galea was rotated and sutured over the exposed bone. Using occlusive hydrocolloid dressings, epithelialization from the galea completely repaired the defect. This case illustrates the high safety of the pediculated flap in the temporal vessels and the high epithelization capacity of the galea.

Case 3, who underwent liver transplantation, received surgical treatment similar to case 2. But in this case, the right flap of the occipital pedicle was shorter, and there were no complications.

In case 4, temporal, frontal, and occipital scars limited the use of flaps. Tissue expansion was the option chosen in the absence of microsurgical resources in a local public hospital in the 1980s. This technique was recommended by Sasaki in 19858, Anger in 19889, and other authors10, followed by cranioplasty Korloff et al., 197311 and some osteosyntheses with steel wires. Despite the extrusion of one synthesis and a small bone fragment, it had no relapse of the fistula, with adequate protection to the brain and excellent aesthetic results. This case illustrates the use of an expanded advancement flap in the unpredictability of temporal flaps.

CONCLUSION

The experience gained in the surgical treatment of these complex and unusual cases indicates the preferred choice of random-pattern large fasciocutaneous flaps with temporal pedicles in the reconstruction of large scalp defects over microsurgery. Distal ischemic suffering may occur in these flaps, but when they are adequately treated, as in the cases presented, excellent aesthetic and functional results are achieved.

COLLABORATIONS

|

JWF |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

KSMP |

Data Curation, Investigation, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

MHM |

Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

REFERENCES

1. Jr CCC. Tumors involving the craniofacial skeleton. In: McCarthy JG, ed. Reconstructive plastic surgery: tumors head neck. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1977. p. 2757-75.

2. Romero RM, Arikat A, Machado Filho G, Aita CD, Oliveira MP, Jaeger MRO. Reconstrução de defeitos no couro cabeludo. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2018;33:90-2.

3. Steiner D, Horch RE, Eyüpoglu I, Buchfelder M, Arkudas A, Schmitz M, et al. Reconstruction of composite defects of the scalp and neurocranium — a treatment algorithm from local flaps to combined AV loop free flap reconstruction. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:217.

4. Souza CD. Reconstrução de grandes defeitos de couro cabeludo e fronte em oncologia: tática pessoal e experiência – análise de 25 casos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(2):227-37.

5. Marchac D. Deformities of the forehead, scalp, and cranial vault. In: McCarthy JG, ed. Plastic surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1990. p. 1538-73.

6. Bradford BD, Lee JW. Reconstruction of the forehead and scalp. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019:27(1):85-94.

7. Jenkins G, Smith AB, Kanatas AN, Houghton DR, Telfer MR. Anatomical restrictions in the surgical excision of scalp squamous cell carcinomas: does this affect local recurrence and regional nodal metastases? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014:43(2):142-6.

8. Sasaki GH. Tissue expansion. São Paulo: Dow Corning Healthcare Centre; 1985.

9. Anger J. Expansão de tecidos. São Paulo: Dow Corning do Brasil; 1988.

10. Fernandes JW. Expansores de pele. In: Fernandes JW, org. Cirurgia plástica - Bases e refinamentos. Curitiba: Primax; 2012. p. 159-70.

11. Korloff B, Nylen B, Rletz K. Bone grafting of skull defects. Plast Reconstr Surg.1973; 52:378-383

1. Universidade Positivo, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

2. Faculdade Evangélica Mackenzie do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Julio Wilson Fernandes Avenida Getúlio Vargas, 2079, Curitiba, PR, Brazil. Zip Code: 80250-180. E-mail: : cirurgiaplasticajwf@uol.com.br

Article received: June 7, 2019.

Article accepted: February 29, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter