Ideas and Innovation - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Chin augmentation with cervical flaps associated with rhytidoplasty

Aumento mentoniano com retalho cervical associado à ritidoplastia

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The lack of chin projection in the lower third of the face is sometimes responsible for the breaking of the facial contour harmony. Alloplastic implants, fillers, and osseous advancements have been used to correct these deformities. In this study, we propose a new maneuver to increase chin projection by using a cervical flap associated with rhytidoplasty.

Methods: We assessed 11 patients who underwent operations using the cervical flap for chin projection between January 2017 and January 2018. The inclusion criteria were only patients who desired chin augmentation without the use of prosthetics, fillers, or osseous approaches, and those who would undergo rhytidoplasty.

Results: A cephalometric analysis revealed improvements in chin projection and cervical contour, and no complications in the immediate or late postoperative period.

Conclusion: In addition to presenting satisfactory results and acceptance, the cervical flap used for chin augmentation eliminated the use of synthetic materials, reduced surgical costs, and improved safety and durability, achieving a more refined mandibular contour and natural chin projection.

Keywords: Mentoplasty; Rhytidoplasty; Chin augmentation; Cervicoplasty; Chin.

RESUMO

Introdução: A falta da projeção mentoniana no terço inferior da face algumas vezes é responsável pela quebra da harmonia do contorno facial. A utilização de implantes aloplásticos, preenchimentos submetidos à ritidoplastia para correção destas deformidades. Neste estudo, propomos uma nova manobra para aumento da projeção mentoniana com uso de um retalho cervical associado à ritidoplastia.

Métodos: Foram avaliados 11 pacientes operados no período de 01/2017 a 01/2018, utilizando-se o retalho cervical para projeção mentoniana, e tendo como critério de inclusão somente pacientes que almejavam um aumento mentoniano, sem utilização de próteses, preenchimentos ou abordagem óssea, e que seriam submetidos à ritidoplastia.

Resultados: Através da análise cefalométrica evidenciou-se melhora da projeção mentoniana e do contorno cervical, e não houve complicações no pós-operatório imediato ou tardio.

Conclusão: O retalho cervical utilizado para aumento mentoniano além de apresentar resultados e aceitação satisfatórios, elimina o uso de materiais sintéticos, redução de custos, segurança e durabilidade, alcançando um contorno mandibular mais refinado e uma projeção mentoniana mais natural.

Palavras-chave: Mentoplastia; Ritidoplastia; Aumento de mento; Cervicoplastia; Queixo

INTRODUCTION

The chin plays a major role in the contour of the lower third of the face; its absence or excess causes an aesthetic rupture and break in facial harmony. The chin morphology is determined by osseous components and soft tissues, which vary with sex and age. Most of the aesthetic changes of the chin are evident mainly in the local osseous component1.

Generally, most complaints encountered in medical practice emphasize discontent with the cervical region. However, without identifying the disproportions of the chin components in the local context, it is up to the physician to ascertain the correct interpretation and suggest the best management for each patient.

OBJECTIVE

To describe a new technique for chin augmentation using a cervical flap associated with rhytidoplasty.

METHODS

This study was a prospective evaluation of 11 female patients between the ages of 40 and 65 years who underwent a chin augmentation with cervical flaps between January 2017 and January 2018, performed by the author through private services (Ferreira Segantini Plastic Surgery–Day Hospital).

We conducted our analysis with the aid of photographic documentation of the patients who underwent the procedure.

Inclusion Criteria

We included only patients who desired a chin augmentation without using prosthetics, fillers, or osseous approaches, and those who would undergo rhytidoplasty.

Surgical Technique

All the surgeries were performed under local anesthesia with sedation, with the patient in the supine position. The process for making the cervical flap precedes the rhytidoplasty, and in some cases, prior liposuction of the cervical region may be performed.

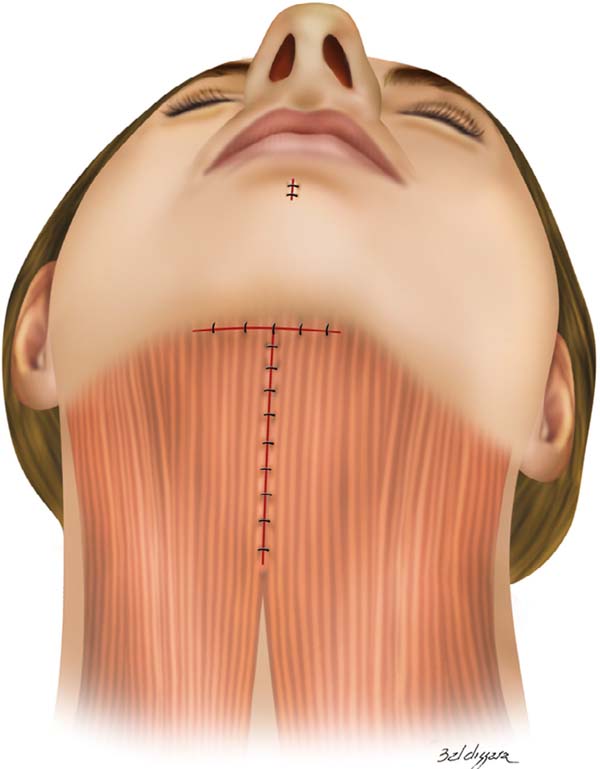

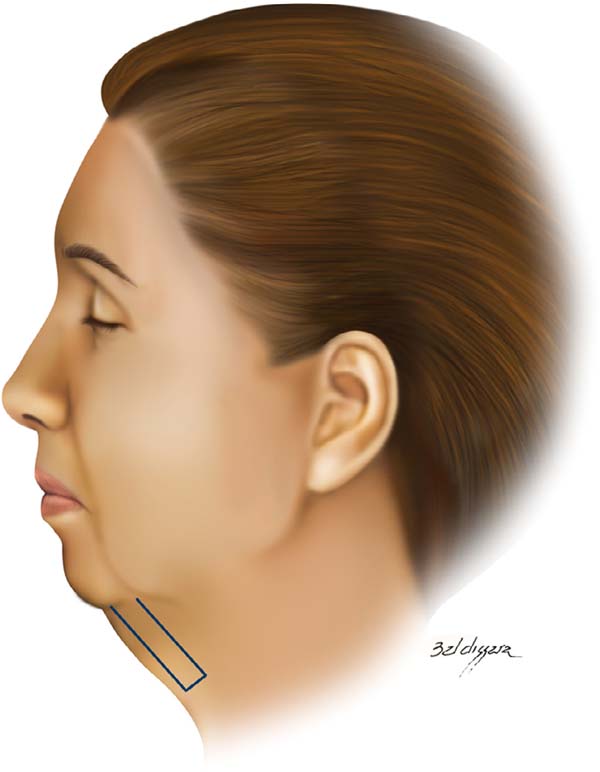

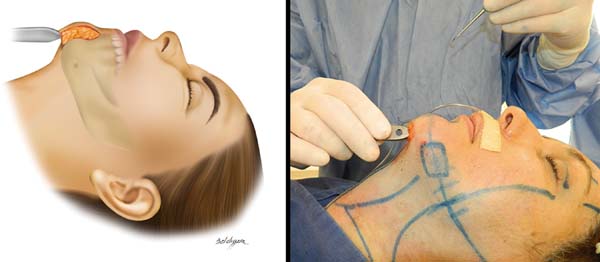

The flap proposed in this technique is located on the cervical midline and consists of segments of the platysma muscle and fatty tissue of the submental space. The base of the flap measures approximately 2.5 cm and begins in the upper submental region, extending inferiorly by 4 to 6 cm (Figures 1 and 2).

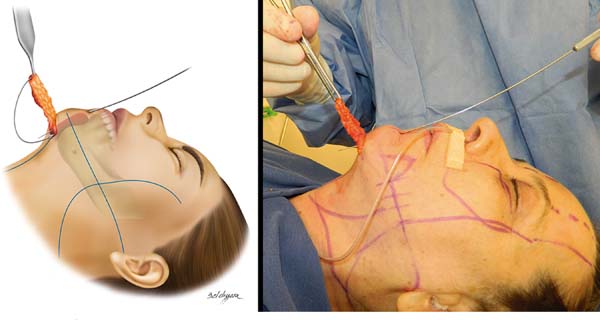

After detaching the cervical skin and making the flap, we began the posterior superior dissection of the flap in the median subperiosteal region of the mandible, 1.5 to 2.0 cm above the mental protuberance². Next, we evaluated the cavity size and volume offered by the flap, which allowed us to make adjustments if necessary (Figure 3).

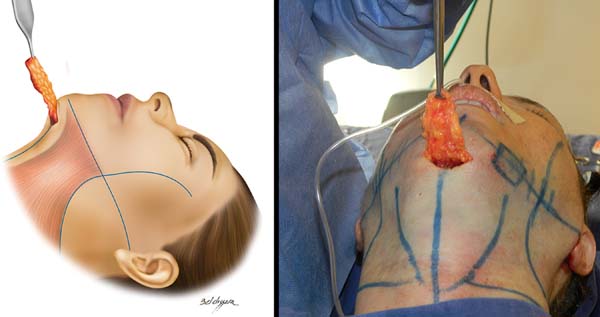

Having made the flap and cavity, we rotated the flap in a posterior superior direction and then affixed it using a transcutaneous needle (e.g., Reverdin) in the upper midline of the cavity (Figure 4). The suture was made with 4.0 mononylon using only a small hole to bury the suture knot.

With the flap attached to the cavity, the base of the flap was stitched to the periosteum of the transition from the mental to submental regions, and the platysmal bands are closed at the midline, where they meet at the base of the flap in a T-stitch (Figure 5), allowing us to proceed to treating the upper and midface (Figure 6).

Postoperative care was similar to that in conventional rhytidoplasty associated with chin implantations.

RESULTS

All the patients underwent a cephalometric analysis, which, in turn, plays a major role in the assessment of the relationship of the chin with other bone structures and soft tissues of the face.

For this study, we considered the imaginary lines created by Frankfurt (horizontal) and Gonzales-Ulloa (vertical and tangent to nasion) (Figure 7).

All the patients presented good recovery and did not present with any complications in the immediate or late postoperative period.

All the patients evidenced an improvement in chin projection, ranging from 32.5% to 60% in relation to the Gonzales-Ulloa line and cervical contour (Figures 8-10).

DISCUSSION

Many procedures have been used to aesthetically improve the lower third of the face, producing efficient results with an effective increase in chin projection.

Silicone implants have been applied the most, as it demonstrates efficient results and are easy to handle. However, approximately 50% of the patients present with bone erosion³ due to local compression of the prosthesis. The most frequent complications include choosing the wrong implant size, prosthetic displacement, infection, extrusion of the implant, sensitive alterations in the lower lip, and impaired chin muscle function, where intraoral access4 is responsible for most complications.

In well-selected cases without occlusion problems, basilar osteotomy5 exhibits excellent results. Despite the low incidence of complications6, patients do not generally accept the procedure owing to fear of bone manipulation.

Despite the easy application, the use of fillers such as hyaluronic acid has temporary results and, in some cases, can cause intense and sometimes prolonged erythema, papulopustular polymorphic acne, intense edema, skin nodules7, and necrosis8. Regardless of their associated low incidence rates of complications and easy treatment, fillers performed with fat grafting7 may show partial or total reabsorption and asymmetries, and some cases might require several sessions to obtain a good result.

Among the strategies to improve chin contour with autologous tissues is the proposal by Viterbo and Brock in 20139 to perform “gliding mentoplasty,” which includes intraoral access and easy execution, and can be performed in isolation without a greater approach to the face. Nevertheless, it may be insufficient in cases that require a volumetric increase.

In comparison with the other procedures, chin augmentation with the use of the cervical flap has been shown to be effective, with real gains in anterior projection, durability, and enthusiastic acceptance by the patients. Furthermore, we have yet to observe any complications.

CONCLUSION

Although making the flap requires a little more experience and surgical time, its results and acceptance are encouraging. By eliminating the use of synthetic materials, reducing costs, and improving safety and durability, a more refined mandibular contour and a more natural chin projection can be achieved.

REFERENCES

1. Reiff ABM, Góes CHFS, Barbosa TA, Mélega JM. Cirurgia estética do perfil e do contorno facila. In: Mélega JM, Baroudi R, ed. Cirurgia plástica fundamento e arte. Cirurgia estética. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): MEDSI; 2003. p. 407-32.

2. Rohen JW, Yokochi C, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Cabeça e pescoço. In: Rohen JW, Yokochi C, Lutjen- Drecoll E, eds. Anatomia humana. Barueri (SP): Manole; 2006. p. 19-23.

3. Fridland JA, Coccaro PJ, Converse JM. Retrospective chefalometric analysis of mandibular bone absorption under silicone rubber chin implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57(2):144-51.

4. Zide BM, Longaker MT. Chin surgery: II. Submental osteoctomy and soft-tissue excision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(6):1854-62.

5. Sofia OB, Telles PAS, Dolci JEL. Mentoplastia no tratamento das deformidades do queixo. Rev Bras Cir Craniomaxilofac. 2009;12(4):169-73.

6. Ramalho GC, Miranda SL, Moreno R, Silva HCL, Miranda MVF. Reabsorção óssea associada ao implante de silicone em mentoplastia: relato de caso clínico. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2017;32(2):291-4.

7. Reiff ABM, Góes CHFS, Barbosa TA, Mélega JM. Rejuvenescimento facial: métodos auxiliares-procedimentos de preenchimento. In: Mélega JM, Baroudi R, eds. Cirurgia plástica fundamento e arte. Cirurgia estética. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): MEDSI; 2003. p. 215-49.

8. Wang Q, Zhao Y, Li H, Li P, Wang J. Vascular complications after chin augmentation using hyaluronic acid. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(2):553-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-017-1036-3

9. Viterbo F, Brock RS. Gliding mentoplasty: a new technique. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37(6):1120-7.

1. Ferreira Segantini Cirurgia Plástica, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Márcio Manoel Ferreira da Cunha Avenida Presidente Médici, Morada da Colina, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil. Zip Code: 38411-012. E-mail: atendimento@ferreirasegantini.com.br

Article received: August 14, 2019.

Article accepted: February 22, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter