Original Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Treatment strategy for benign nerve tumors

Estratégia de tratamento nos tumores benignos de nervo

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Peripheral nerve tumors are usually benign, rare, slow-growing and little symptomatic. The objective is to describe strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with benign tumors of the ulnar nerve.

Methods: This retrospective study of patients who underwent surgery between 2010 and 2015 for the treatment of benign tumor of the ulnar nerve analyzed patient symptoms and demographic characteristics, complementary examinations, and surgical techniques performed.

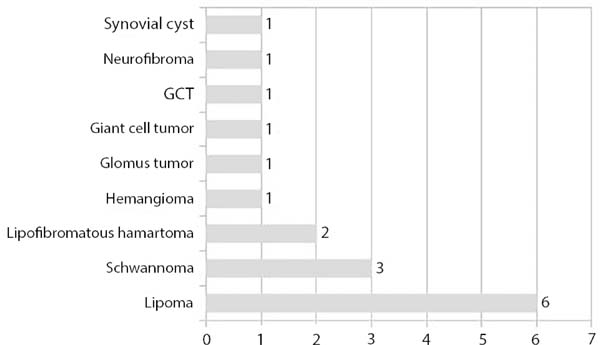

Results: The study included 17 (8%) patients, with a prevalence of women (65%) in the fourth decade of life. The tumors tended to be extrinsic, with lipoma in 6 cases (35%); others were intrinsic, including schwannoma in 17% and hamartoma in 11% of the cases. Tumor excision was complete in 83% of cases and partial in 17% of cases; nerve decompression was performed in 12 cases.

Conclusion: The strategies performed here yielded good functional results in 88% of patients. The worst results were in tumors of vascular origin.

Keywords: Ulnar nerve; Ulnar nerve compression syndromes; Neoplasms; Surgery, Plastic; Microsurgery.

RESUMO

Introdução: Os tumores de nervo periférico normalmente são benignos, raros, de crescimento lento e pouco sintomáticos. O objetivo é descrever estratégias para o diagnóstico e tratamento de pacientes com tumores benignos que afetam o nervo ulnar.

Métodos: Estudo retrospectivo dos pacientes operados entre 2010 e 2015 com tumor benigno de nervo ulnar, segundo os sintomas, exames complementares, técnicas cirúrgicas realizadas e características demográficas.

Resultados: O estudo incluiu 17(8%) pacientes, prevalência sexo feminino (65%) na quarta década de vida; e, natureza extrínseca, o lipoma, em seis casos (35%), seguido do tumor de origem intrínseca, o Schwannoma em 17% e hamartoma em 11%. A excisão tumoral foi total em 83% casos e parcial em 17% casos; em doze casos realizou-se a descompressão neural.

Conclusão: Com as estratégias realizadas para o tratamento foi possível bons resultados funcionais em 88% dos pacientes operados. Os piores resultados foram nos tumores de origem vascular.

Palavras-chave: Nervo ulnar; Síndromes de compressão de nervo ulnar; Neoplasias; Cirurgia plástica; Microcirurgia

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral nerve tumors are usually benign, slow growing, poorly symptomatic, and uncommon. Several cases of tumors of the ulnar nerve have been reported in the literature, primarily in the wrist and elbow, and may cause compressive syndromes, mainly in Guyon’s canal and the cubital canal1-5. Guyon’s canal, first described in 1861, is located in the wrist and formed by a bone floor and fibrous ceiling, pisiform, hamate hook, carpal ligament, tendon insertion of the ulnar flexor of the carpus, pisohamate ligament, and tendon of the short palmar muscle. The cubital canal is located in the elbow and bound by the arcade of Struthers, intermuscular septum, medial epicondyle, medial portion of the triceps, Osborne’s band, pronator and flexors aponeurosis, and arcade of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle1-3. As with the median nerve, the ulnar nerve and other peripheral nerves can be affected by tumors originating from the neural sheath as well as schwannoma and neurofibroma; intraneural, such as lipoma, hemangiomas, hamartomas, or cysts; and extrinsic, including lipoma, cysts, and bone tumors1-5.

Upon clinical evaluation, tumors manifest with growth on the ulnar edge of the wrist, hand, or elbow and may be asymptomatic or manifest as sensory changes, with paresthesia of the ulnar edge of the hand in the fourth and fifth fingers; Froment’s sign and a positive Tinel’s sign; and decreased motor force of the intrinsic muscles of the hand as well as clamp, grip, and cubital claw strength. Sensitivity tests (Semmes-Weinstein) and motor assessments are required for its diagnosis2. According to the noted changes, compression syndromes are classified into: type I - compression with sensory and motor deficits; type II - compression of the deep branch with motor changes; and, type III, compression of the superficial branch consisting of sensory deficits without motor impairments3.

Complementary electrophysiological, tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasonography studies are performed to assess the tumor nature, site, size, invasion, necrosis; nerve functionality and malignancy; and aspect of the neighboring tissues. Tumors originating from the neural sheath are confirmed by incisional or excisional biopsy as well as microscopy and immunohistochemistry studies (S-100 and Leu-7).

The most common benign tumors originating from the neural sheath are Schwannomas (cellular and plexiform) and neurofibromas (solitary or plexiform)6. Other tumors can compromise the ulnar nerve, originating from the sheath and other structures, such as the giant cell tumor, lipoma, myxoma, hemangioma, lipofibromatous hamartoma, hemangioblastoma, meningioma; or extrinsic, such as synovial cysts or bone tumors, causing neural compression in the wrist, in the Guyon canal or in the elbow, in the cubital canal.

The tumor located in a single neural fascicle can be removed and repaired with neurorrhaphy or nerve grafting, and nerve function can be preserved. However, in some situations of tumor growth, depending on the type of tumor and time of evolution, tumor exeresis can cause irreversible cubital paralysis.

Although benign tumors that affect the ulnar nerve are rare, there is a variety of tumors and it is important the diagnosis to definition of strategies for treatment and prognosis.

OBJECTIVE

Here we aimed to describe the treatment provided for patients with benign tumors of the ulnar nerve at the Hospital SARAH Brasília between 2010 and 2015.

METHODS

This was a retrospective study of medical records of patients treated in the Hospital SARAH Brasilia between 2010 and 2015 for benign tumors of the wrist and elbow with ulnar nerve impairment. These tumors were divided into 2 categories: those that originated from the neural sheath and not from the neural sheath; and those that were asymptomatic or with compressive symptoms of the ulnar nerve. The study was evaluated and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (opinion CEP/APS no. 53559216.0.0000.0022).

Inclusion criteria: Only benign tumors of the ulnar nerve originating from the neural sheath, with an intraneural or extrinsic location, and with or without compression syndrome of the ulnar nerve at the wrist or elbow.

Exclusion criteria: Tumors of traumatic origin, malignant tumors of the ulnar nerve, and tumors of other nerves in the wrist and upper limb.

Studied variables: Sex, age, signs and symptoms; electroneuromyography, imaging exams with computed tomography, ultrasonography, nuclear magnetic resonance, and histopathological and immunohistochemical study findings; and surgical procedure and outcome.

Statistical Analysis: Data were analyzed using Epi-info 3.2.2 software.

Physiotherapeutic assessment

The patients were evaluated preoperatively and in the sixth postoperative month by physiotherapists using a Semmes-Weinstein sensitivity map and a motor map according to the Louisiana State University Medical Center Grading System for Motor and Sensory Function.

Surgical technique

Patients underwent surgical procedures under hospitalization with general anesthesia or a brachial plexus block; asepsis and antisepsis measures; placement of surgical fields; emptying of the upper limb with an Esmarch band; and placement of a pneumatic tourniquet with a pressure of 100 mmHg above the systolic pressure;

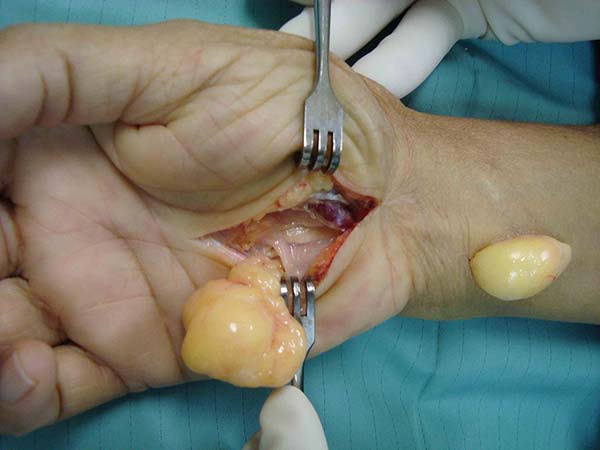

In the wrist – A transverse or zigzag incision (Figure 1) was made at the ulnar edge of the hand and wrist; alternatively, an incision was made on the medial edge of the proximal phalanx of the little finger to the radial edge of the hypothenar eminence next to the abductor muscle of the finger (Figure 2). Tissue dissection and identification of the neurovascular bundle; opening of the Guyon’s canal; tumor excision; hemostasis; and suture with 5-0 mononylon thread were performed. An occlusive dressing with gauze and a crepe bandage were applied with the wrist in a functional position.

In the elbow – A 10- to 12-cm incision, or according to the size of the tumor, was made in the medial portion of the elbow. The tissues and nerve were dissected from proximal to distal with preservation of the medial cutaneous branch of the forearm and the branches of the ulnar nerve. After opening of the intermuscular septum and arcade of Struthers, the intrinsic or extrinsic tumor was excised with anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve in the subcutaneous tissue and preservation of the vascularization. At the end, after hemostasis, a subcutaneous suture with monocryl 3-0 and immobilization with a double support sling were applied and the elbow kept flexed for 2 weeks.

RESULTS

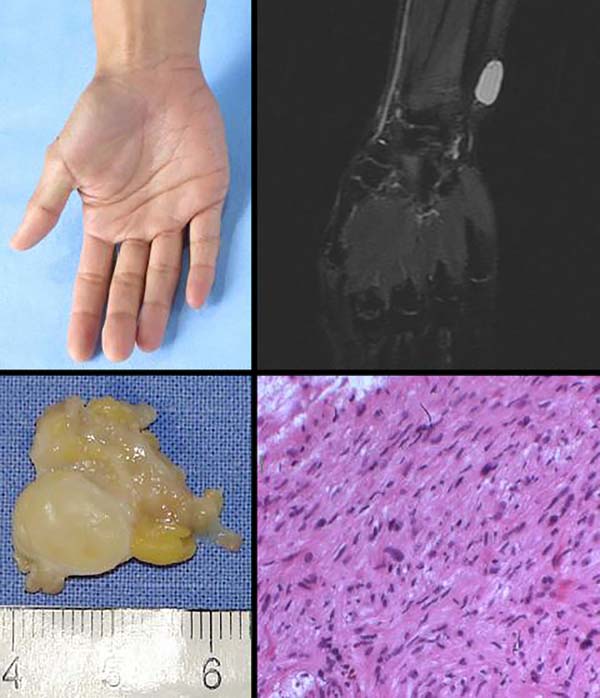

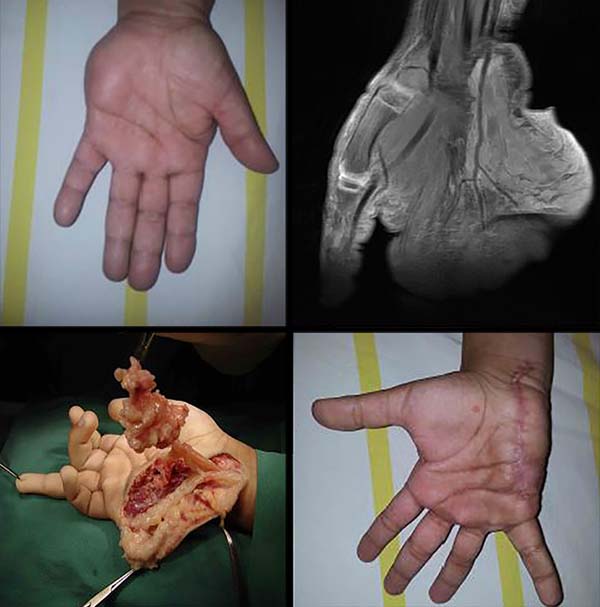

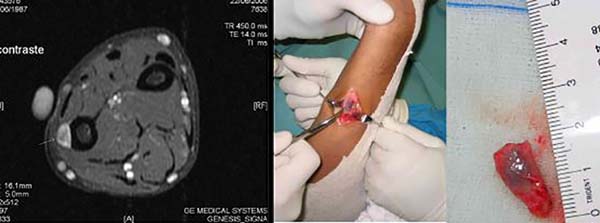

A total of 220 patients with benign tumors in the upper limbs were treated between 2010 and 2015; of them, 17 (8%; 11 women, 6 men; age range, 7–58 years; predominance in the fourth decade of life) (Figure 1, Table 1). The most frequent tumor was lipoma in 6 cases (35%) (Figures 2 and 3), followed by tumor of intrinsic origin, schwannoma in 3 cases (17%) (Figure 4); and hamartoma in 2 cases (11%) (Figure 5). The other tumors were individual cases and are distributed in Table 2 (Figures 6 and 7). Tumor excision was complete in 14 (83%) cases and partial in 3 (17%) cases; neural decompression was performed in the Guyon’s canal in 8 cases, and in 4 in the elbow. A patient with glomus tumor was initially operated at 9 years of age and presented recurrence ten years after and was reoperated (Figure 7). The average follow-up time was 6 months (range, 3 months to 10 years).

| Tumor | Location | N | Surgical Procedures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipoma | 4 wrist and hand 2 elbow |

6 | 3 - total tumor resection + neural decompression 3 - total extraneural tumor resection |

Normal |

| Schwannoma | 1 elbow 2 fist |

3 | Total intraneural tumor resection + neural decompression |

Normal |

| Lipofibromatous hamartoma |

2 wrist and hand | 2 | Disarticulation of finger + neural decompression and partial tumor resection |

1 - improvement in function and electromyographic findings1 - maintenance of electromyographic findings |

| Hemangioma | Fist | 1 | Partial resection + neural decompression + partial tumor resection |

Persistence compressive symptoms |

| Synovial cyst | Distal forearm | 1 | Total tumor resection | Normal |

| Glomus tumor | Forearm | 1 | Partial tumor resection | Tumor recurrence, ulnar paresthesia |

| Giant cell tumor | Fist | 1 | Tumoral resection + neural decompression |

Normal |

| Neurofibroma | Wrist and hand | 1 | Intraneural resection + neural decompression + partial tumor resection |

Improvement in function and pain |

| Gouty tophus | Elbow | 1 | Tumor resection and neural decompression + partial tumor resection |

Normal |

| Total | 17 |

| Tumor | N | Positive compressive symptoms |

Electroneuromyography positive for ulnar nerve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipoma | 6 | 3 | Normal |

| Lipofibromatous hamartoma | 2 | Negative | 1 sensory lesion of the fifth finger 1 normal |

| Hemangioma | 1 | Negative | Normal |

| Synovial cyst | 1 | Negative | Normal |

| Glomus tumor | 1 | 1 | 1 lesion of the ulnar nerve motor fibers, discreet, without denervating activity |

| Giant cell tumor | 1 | 1 | Normal |

| Neurofibroma | 1 | 1 | Normal |

| Gouty tophus | 1 | 1 | 1 myelin lesion of the ulnar nerve on the elbow |

DISCUSSION

Tumors that affect the ulnar nerve are rare, occurring mainly in Guyon’s canal and the cubital canal7-13. Clinically, patients can be asymptomatic or have a history of tumor growth, pain, paresthesia, and abnormalities of the ulnar nerve. An electroneuromyography examination is important to evaluating the degree of lesion in the nerve, revealing changes in 3 cases, mainly of a tumor of vascular origin. Even in the case of a neurofibroma, with extensive involvement of the ulnar nerve, an electromyographic examination may be normal. Imaging tests, such as x-rays, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging, are important to identifying the cause of the compression, while the target sign is important for confirming the diagnosis of schwannoma4,5. Ultrasonography examinations have increasingly contributed to the complementary diagnosis.

Making the surgical decision is of the major problems encountered when treating patients with neural tumors since many tumors are slow growing and asymptomatic; thus, the specific strategies require a functional electroneuromyography diagnosis, definition of tumor size and location, and, if possible, tumor type to aid in surgical planning, postoperative follow-up, and prognosis assessment. Microsurgery, magnifying objects, and microsurgical material were used in all surgeries, and no cases required neural reconstruction.

Regarding origin, the tumors evaluated in this series were mainly of a lipomatous nature, followed by those of Schwann cells, synovial cysts, and others. Tumors of vascular origin, as evidenced in 2 cases (hemangioma and glomus tumor), usually originate in the nerve roots and retrobulbar and cranial nerves; there are few reports of hemangiomas arising in the distal peripheral nerves, including the radial and digital nerves. Structurally, they arise from blood vessel dilation13,14.

Partial resection was performed in cases of hemangioma, glomus tumor, lipofibromatous hamartoma, and neurofibroma, as they compromised the neural fascicles. Surgery was performed in accordance with the microsurgical technique with the aim of reducing the tumor component as well as a histological study and diagnostic confirmation; recurrence was observed in the case of glomus tumor. The surgical approach was specific for each tumor type, with complete or partial tumor excision, associated neural decompression, and neural reconstruction when necessary. In cases of lipofibromatous hamartoma associated with macrodactyly, amputation was necessary to improve functionality.

A prevalence of synovial cysts associated with neural compression in the wrist and elbow is observed in the literature with surgical indication9-13; this finding was observed in only 1 case in our study. In cases of intraneural or extrinsic cystic tumors that cause neural compression, the events that follow include nerve compression, followed by endoneurial ischemia, edema, and microcompartment syndrome. This causes nerve damage with segmental demyelination and remyelination; degeneration of axonal regeneration; and proliferation of endoneurial cells, fibroblasts, and capillary endothelial cells; thus, thickening and fibrosis of the perineurium and epineurium occur as evidenced in the clinical assessment and on imaging examinations and electroneuromyography15.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we identified good recovery (88%) of the operated cases of tumors involving the ulnar nerve. Although total tumor excision was not possible in cases of neurofibromas and hamartomas, it was possible to control tumor growth and neural compressive symptoms. The worst results were identified in cases of hamartomas and glomus tumor with tumor recurrence. The need for strategies to identify tumor type and location, neurophysiological changes, and the need for a microsurgical procedure for tumor excision was demonstrated.

COLLABORATIONS

|

KTB |

Conception and design study, Project Administration, Writing - Original Draft Preparation |

|

VCSM |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Project Administration |

|

RSS |

Conceptualization, Supervision |

|

UPYS |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Methodology |

|

ICC |

Resources |

|

CZC |

Conceptualization |

|

CFPAS |

Writing - Review & Editing |

REFERENCES

1. Lundborg G, Rosén B. Hand function after nerve repair. Acta Physiol. 2007;189(2):207-17.

2. Lundborg G. A 25-year perspective of peripheral nerve surgery: evolving neuroscientific concepts and clinical significance. J Hand Surg. 2000;25A:391-414.

3. Mattar Júnior R. Síndromes compressivas do membro superior. In: Hernandez AJ, editor. Ortopedia do adulto. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 2004. p. 83-97.

4. Matejcik V, Benetin J, Danis D. Our experience with surgical treatment of the tumours of peripheral nerves in extremities and brachial plexus. Acta Chir Plast. 2003;45(2):40-5.

5. Duba M, Smrcka M, Lzicarova E. Effect of histologic classification on surgical treatment of peripheral nerve tumors. Rozhl Chir. 2003;82(3):138-41.

6. Rockwell GM, Thoma A, Salama S. Schwannoma of the hand and wrist. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1227-32.

7. Staples JR, Calfee R. Cubital tunnel syndrome: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25(10):e215-e224.

8. An TW, Evanoff BA, Boyer MI, Osei DA. The prevalence of cubital tunnel syndrome: a cross-sectional study in a U.S. metropolitan cohort. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(5):408- 16.

9. Desy NM, Wang H, Elshiekh MA, Tanaka S, Choi TW, Howe BM, et al. Intraneural ganglion cysts: a systematic review and reinterpretation of the world’s literature. J Neurosurg. 2016;125(3):615-30.

10. Mobbs RJ, Phan K, Maharaj MM, Chaganti J, Simon N. Intraneural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve at the elbow masquerading as a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:613.e5-e8.

11. Colbert SH, Le MH. Case report: intraneural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve at the wrist. Hand. 2011;6(3):317-20.

12. Öztürk U, Salduz A, Demirel M, Pehlivanoğlu T, Sivacioğlu S. Intraneural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve in an unusual location: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;31:61-4.

13. Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 146 peripheral non-neural sheath nerve tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(2):246-55.

14. Gregoli B, Bortolotto C, Draghi F. Elbow nerves: normal sonographic anatomy and identification of the structures potentially associated with nerve compression. A short pictorial-video article. J Ultrasound. 2013;16(3):119-21.

15. Prinz RA, Nakamura-Pereira M, De-Ary-Pires B, Fernandes D, Fabião-Gomes BD, Martinez AM, et al. Axonal and extracellular matrix responses to experimental chronic nerve entrapment. Brain Res. 2005;1044:164-75.

1. Hospital Sarah Brasília da Rede Sarah de Hospitais de Reabilitação, Brasília, DF,

Brazil.

2. Centro Universitário do Planalto Central Aparecido dos Santos, Brasília, DF, Brazil.

3. Secretaria de Estado de Saúde Fundação de Ensino e Pesquisa em Ciências da Saúde,

Brasília, DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Katia Torres Batistae SMHS 501, Bloco A, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Zip Code: 70335-901. E-mail: katiatb@terra.com.br

Article received: June 13, 2019.

Article accepted: October 21, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter