Original Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Triangular flap for nipple reconstruction

Retalho triangular para reconstrução da papila mamária

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Despite the many published techniques, there are difficulties in satisfactorily achieving a nipple areola complex (NAC) with long-lasting results. The objective is to demonstrate results using the triangular cutaneous flap technique in nipple reconstructions and compare it with previously published techniques.

Methods: A prospective study of nipple reconstruction using the triangular cutaneous flap technique from January 1, 2015, to March 1, 2016. Surgical technique: Marking of an equilateral triangle; decortication of the three points of the triangle that are united in the form of an envelope, with the central area adhered to the neo-breast; total skin grafting for construction of the areola. The patients were evaluated and results classified as fully satisfactory, satisfactory, partially satisfactory, or unsatisfactory. Primary type of breast reconstruction, postoperative or neoadjuvant chemo- or radiotherapy complications, comorbidities, and postoperative complications were evaluated. Statistical evaluation was performed using Fisher's exact test, chi-square test, and post hoc analysis (significance p < 0.05).

Results: Thirty-one patients underwent nipple reconstruction using the triangular cutaneous flap technique, 17 unilateral and 14 bilateral, totaling 45 reconstructions. Mean age was 50 years, mean body mass index was 24.95 kg/m2, and mean follow-up period was 14 months. Rated: demographic data, complications of patients versus the type of primary breast reconstruction and completion of chemo- and/or radiotherapy, types of breast reconstruction performed, evaluation of the nipples versus reconstruction, evaluation of the nipple reconstruction technique versus satisfaction of evaluators, and nipple complications versus reconstruction technique.

Conclusion: The original triangular cutaneous flap technique presents the advantages of easy execution and safety in reconstruction of the NAC.

Keywords: Breast; Nipples; Breast neoplasms; Mammoplasty; Diagnostic surgery techniques.

RESUMO

Introdução: Apesar das muitas técnicas publicadas, há dificuldades para se atingir de forma satisfatória uma placa areolopapilar (PAP) com resultado duradouro a longo prazo. O objetivo é demonstrar resultados pela técnica do retalho cutâneo triangular nas reconstruções de papila e comparar com as técnicas já descritas na literatura.

Métodos: Estudo prospectivo da reconstrução papilar pela técnica do retalho cutâneo triangular de 1 janeiro de 2015 a 1 de março de 2016. Técnica cirúrgica: Marcação em triângulo equilátero; decorticação dos três vértices do triângulo que são unidos em forma de envelope, com a área central aderida à neomama; Enxertia de pele total para confecção da neoareolar. Os pacientes foram avaliados e classificados como totalmente satisfatórios, satisfatórios, parcialmente satisfatórios ou insatisfatórios. Tipo de reconstrução mamária primária, realização de quimio ou radioterapia pós-operatórias ou neoadjuvantes, comorbidades, complicações pós-operatórias foram avaliados. Avaliação estatística por testes exato de Fisher, Qui quadrado e análise post hoc (p < 0,05 significativo).

Resultados: Trinta e uma pacientes submetidas à reconstrução mamilar pela técnica do retalho cutâneo triangular, sendo 17 unilaterais e 14 bilaterais, totalizando 45 reconstruções. Média de idade de 50 anos, IMC médio de 24,95 kg/m2 e acompanhamento médio de 14 meses. Avaliados: dados demográficos, complicações dos pacientes versus o tipo de reconstrução primária mamária e realização de quimio e/ou radioterapia, tipos de reconstrução mamária realizados, avaliação das papilas versus reconstrução, avaliação da técnica de reconstrução papilar versus satisfação dos avaliadores e complicações papilares versus técnica de confecção.

Conclusão: A técnica original do retalho cutâneo triangular apresenta as vantagens de fácil execução e segurança na reconstrução das placas areolopapilares.

Palavras-chave: Mama; Mamilos; Neoplasias da mama; Mamoplastia; Técnicas de diagnóstico por cirurgia

INTRODUCTION

The nipple-areolar complex (NAC) should be considered a single esthetic unit in breast reconstruction, because it represents the final stage in breast reconstitution, in cases in which there is amputation of this complex during mastectomy1. After the preparation of the NAC, the neo-breast acquires an appearance as similar as possible to the contralateral breast.

Several techniques have been published in recent years, with the aim of achieving the best shape and projection of the NAC2-14. However, most present controversial results, some considered very good and others frustrating. The loss of projection seems to be more prominent with the use of certain techniques compared with others.

The loss of projection and final result of nipple reconstructions are related to a number of reasons: scarce subcutaneous flap tissue, poor planning of flaps, natural process of wound contraction, tissue memory, increased internal (tense sutures) or external pressure (e.g., the pressure exerted by a bra), infection, and prior radiation1-18.

Thus, the main challenge is to rebuild a nipple that is able to overcome these local obstacles and natural tendencies18. In breast reconstruction, the NAC should be considered a single esthetic unit, because it represents the final stage in breast reconstitution, in cases in which there is amputation of this complex during mastectomy1. After the preparation of the NAC, the neo-breast acquires an appearance as similar as possible to the contralateral breast.

According to the work of Broadbent et al.2, patients and partners evaluate better the outcome of the breast when the reconstruction of this anatomical unit is completed compared with patients who do not undergo NAC reconstruction. In addition, satisfaction is related to the sustained projection of the nipple (especially in the long term) and absence of complications2.

Millard et al.5, in 1971, described the so-called “nipple banks.” Originally, it consisted of the withdrawal of the NAC and transfer to the buttocks, groin, or abdomen as total skin graft during mastectomy. After the reconstitution of the breast, the grafts were collected and used for NAC reconstruction. Doubts in relation to the safety of this method arose after description of cases in which patients had lymph node involvement, with mammary cells in the inguinal region when using the groin area as “nipple bank”.

In the last 20 years, the defining step in NAC reconstruction techniques has been the use of local flaps. The first technique was published by Berson6, in 1946, which involved preparing three triangular skin flaps that would be raised and sutured to form a nipple projection. In 1984, Little7 created the skate flap, which became the most popular flap used for NAC reconstruction. This is a vertical dermal fat flap that is raised, and both wings are wrapped around a central fat core to ensure adequate nipple projection. To recompose NAC color, skin tattooing was used.

Multiple alterations of this technique have emerged since then. A very efficient technique was described by Shestak and Nguyen8 called double opposing flap. This technique enables the reconstruction of the NAC with appropriate diameter and good projection, symmetrical to the contralateral side, with the possibility of closing the donor area and with all the scars contained in the topography of the new rebuilt areola.

Published evidence shows the difficulties in achieving a satisfactory NAC, due to variations of local flaps. The projection may be difficult to maintain, especially in patients with flaccid, thin, or irradiated skin. Some patients do not feel comfortable with the projection of the nipples all the time. Others reject surgical approaches, because they do not desire another surgical procedure. Finally, in irradiated patients, skin tattooing may be a safer option considering the increase in the rate of complications of other techniques in these patients. Spears et al.15 reported that 84% of their patients were satisfied with skin tattoo and 86% would choose tattooing again15-16.

The loss of projection and the final result of the reconstructed nipples are related to a number of reasons: scarce subcutaneous flap tissue, poor planning of flaps, natural process of wound contraction, tissue memory, increases internal (tense sutures) or external pressure (the pressure exerted by a bra, for example), infection, and prior radiation1,16. Thus, the main challenge is to rebuild a nipple that is able to overcome these local obstacles and natural tendencies16.

METHODS

A prospective study of a series of 31 patients who submitted to a second breast reconstruction was conducted, in which 45 NACs (17 unilateral and 14 bilateral) were reconstructed using the inverted triangular skin flap technique for nipple construction, from January 1, 2015, to March 1, 2016, in two hospitals in Brasilia, DF, Brazil.

Because of its versatility, the technique was used after breast reconstruction with a transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap, with the latissimus dorsi muscle (LDM), reconstructions with silicone implant and expanders, regardless of the presence of scars in the donor area or scarcity of cutaneous or subcutaneous tissue.

The development of the new technique was based on studies to optimize the long-term projection and shape and minimize complications such as necrosis and unsatisfactory results. All surgeries were performed by the same plastic surgeon.

Thirty-one patients who underwent nipple reconstruction using the triangular cutaneous flap technique were analyzed, 17 unilateral and 14 bilateral reconstructions, totaling 45 reconstructions.

The sample exclusively consisted of women, with a mean age of 50 years (ranging from 32 to 64 years), body mass index (BMI) of 24.95 (ranging from 20.76 to 36.76 kg/m2), and mean follow-up of 14 months (ranging from 12 to 18 months).

All patients underwent total mastectomy.

Surgical technique

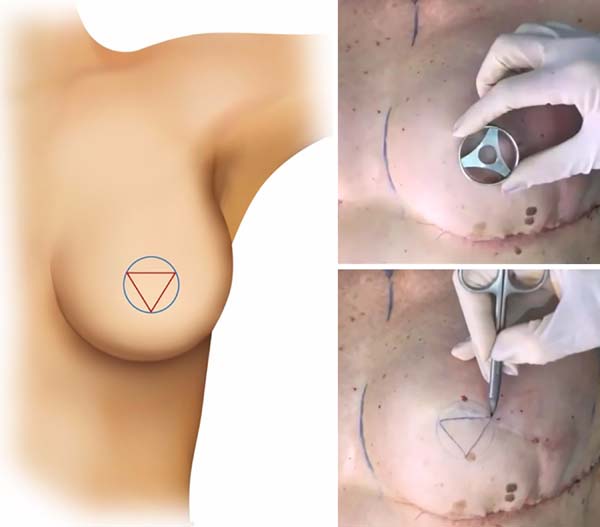

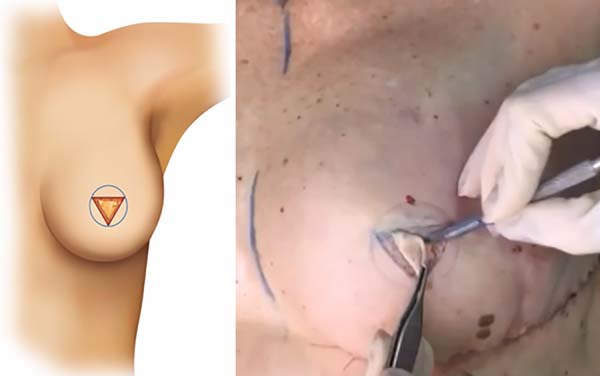

The “inverted triangular” format - the original technique of the inverted triangular cutaneous flap-presents an innovative characteristic, which differs from the usual forms of papillary markings already proposed in literature. Figure 1 illustrates the schematic drawing of the inverted triangular cutaneous flap.

Like most local flaps, this NAC construction technique should be performed after obtaining stability of the neo-breast projection in the second or third stage of breast reconstruction.

In unilateral breast reconstructions, one should initially consider the position of the contralateral nipple, projection and the diameter of the base, and horizontal and vertical measures of the areola to achieve the greatest possible symmetry of the reconstructed NAC. Taking the opposite areola in cases of unilateral reconstruction, the flap is drawn with the papilla located at the point of greatest projection of the neo-breast. The width of the base of the opposing nipple and its projection determine the size of the flap to be drawn.

In cases of bilateral reconstructions, this measure should be projected in accordance with the peculiarities of each case, which provides greater versatility.

For a better explanation of the inverted triangular cutaneous flap technique, 5 steps are described:

Step 1 - Marking

Previous markings are performed according to Figure 1, forming an equilateral triangle within the limits of the neo-nipple.

Step 2 - Decortication

Total decortication of the three points of the triangle forms 3 skin flaps, with maintenance only on the fixed center in its bed (Figure 2).

Step 3 - Initial nipple structure

The 3 vertices of the triangle (A, B, and C) are united in the form of a folding envelope, keeping only the central area of Figure 2 adhered to the neo-breast (Figure 3).

Step 4 - Final nipple construction

Simple sutures are carried out for the coaptation of the edges, and then, the construction of the neo-nipple is finalized (Figure 3).

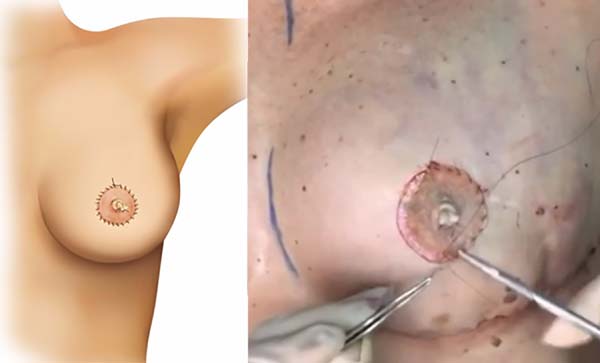

Step 5 - Areola grafting

Full skin excision from the crural region is used to make the neo-areola with a central opening for the emergence of neo-nipple already constructed in all patients. Continuous suturing is performed on the skin graft (Figure 4).

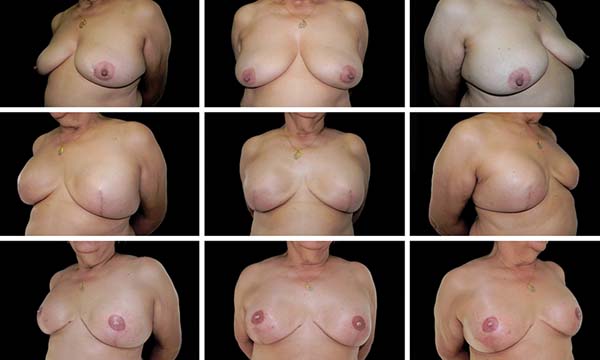

The results were evaluated by photographic documentation preoperatively and postoperatively and preoperatively and late postoperatively in the second reconstruction phase by three plastic surgeons who had not participated in the surgeries.

The evaluations were performed through pictures, considering the defined criteria. In the case of unilateral reconstructions, the results from the likeness and naturalness of the neo-nipple with the contralateral nipple were analyzed. The measurement performed with ruler of the contralateral nipple and comparison of the neo-nipple values were used to assess similarity. In the bilateral cases, the similarity in projection and naturalness of the appearance (base of the areola being twice the apex) were considered, respecting the feasibility of the flaps. Based on these criteria, the neo-nipple was classified as satisfactory or very satisfactory.

Data such as type of primary reconstruction, laterality, achievement of postoperative or neoadjuvant chemo- and radiotherapy, comorbidities, and postoperative complications were also retrieved from the analysis of medical records.

Statistical evaluation of the results was performed by Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test, and post hoc analysis, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

The present study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, on June 1964, and corrected by the 29th Medical Assembly, Tokyo, Japan, on October 1975, and the 35th World Medical Assembly, Venice, Italy, on October 1983, and the 41st World Medical Assembly, Hong Kong, on September 1989.

RESULTS

Among all patients who submitted to the new nipple construction technique, 25 patients underwent neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, and 16 patients underwent postoperative radiotherapy (Table 1).

| Number of patients (n) | 31 |

|---|---|

| NeoNAC | 45 |

| Laterality: unilateral | 17 |

| Bilateral | 14 |

| Mean age (mean ± SD) | 50.7 ± 2.3 |

| BMI - kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 24.95 ± 3.4 |

| Number of surgeries performed | 50 |

| Total mastectomy | 31 |

| Treatment: chemotherapy | 25 |

| Radiotherapy | 16 |

| Comorbidities: | |

| SAH | 6 |

| DM | 3 |

| Smoking | 10 |

| Hypothyroidism | 7 |

| Depression | 7 |

| Histopathological examination | |

| IDC (%) | 24 |

| DCIS (%) | 8 |

| ILC (%) | 3 |

Various comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hypothyroidism, and depression were observed in approximately 80% of patients, however, without significant influence in the evolution of the neo-nipple.

The demographic data of the patients and their characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 2 presents the incidence of complications in the reconstruction of the nipple in relation to the type of primary breast reconstruction (silicone implant, latissimus dorsi, expander, or TRAM) and chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. This analysis showed no statistical significance.

| Complications | Loss of Projection | Necrosis Partial | Good Evolution | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicone Implant | 4 | 1 | 14 | 0.741 |

| Latissimus dorsi | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Expander | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| TRAM | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Therapy | Loss of Projection | Necrosis Partial | Good Evolution | p |

| Chemotherapy | 4 | 1 | 20 | 0.883 |

| Radiotherapy | 2 | 0 | 16 | 0.299 |

Of all nipple reconstructions performed, 5 patients needed to be complemented with polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) for filling and better nipple contour, and only 1 patient evolved with a small area of partial necrosis. No treatment was necessary in the last patient, only dressings, and it did not compromise the final result. These results are presented in Table 2.

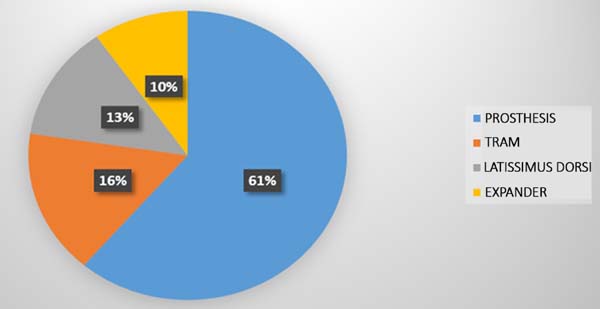

The main form of primary breast reconstruction was performed with the use of silicone implants (n=19), which totaled more than 60%. The other types were the TRAM flap (n = 5), latissimus dorsi muscle (n = 4), and the use of expanders (n = 3). The types of breast reconstruction performed in the sample are quantified in Graph 1 (Figure 5).

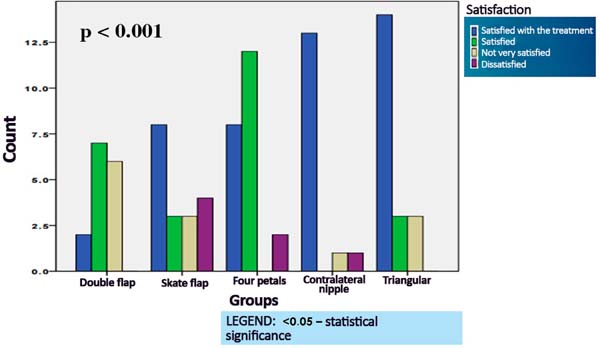

Logistic regression was performed through post hoc analysis to identify which nipple reconstruction technique attained higher index of satisfaction of the evaluators. The triangular cutaneous flap technique for nipple reconstruction attained the highest levels of total satisfaction, with statistical significance p < 0.01 (Graph 2) (Figure 6).

Table 3 shows the comparative results of postoperative assessment of neo-nipple according to the type of primary breast reconstruction. After analysis using Fisher’s exact test, all reconstructions showed minimal variation in their evaluation, which denotes a statistical significance (p = 0.48).

| Evaluation of the nipples X Type of reconstruction |

Expander (15) |

TRAM (27) |

Latissimus dorsi (36) |

Silicone implant (24) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS | 10 (66.66%) | 14 (51.85%) | 17 (47.22%) | 16 (66.66%) | p < 0.48 |

| S | 0 (0.00%) | 9 (33.33%) | 11 (30.55%) | 4 (16.66%) | |

| PS | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (3.70%) | 6 (16.66%) | 4 (16.66%) | |

| U | 3 (20%) | 3 (11.11%) | 2 (5.55%) | 0 (0.00%) |

Table 4 presents the nipple complications due to the type of technique used for its construction. The post hoc analysis showed p < 0.001 in the comparison between the contralateral nipple and 4-petal technique (for clearing factor), p < 0.001 in the comparison between contralateral nipple and skate flap (necrosis), and p < 0.001 in the comparison between contralateral nipple and double-opposing flap (for necrosis) (Table 4).

| Complications | Double flap (15) | Skate flap (18) | 4 Petals (22) | Contralateral nipple (15) | Triangular (20) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slight necrosis | 2 (13.4%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0.001 |

| NAC asymmetry | 1 (6.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Erasure | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (25.0%) | |

| Partial loss of the graft | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Without complications | 12 (80.0%) | 14 (77.8%) | 14 (63.6%) | 15 (100.0%) | 14 (70.0%) |

Figures 7 to 12 display the surgical results of the sample in which the triangular cutaneous flap technique was used in the reconstruction of the nipples.

DISCUSSION

The excellence of the results in nipple reconstructions is acquired when one attains symmetry in position, shape, size, and texture, in addition to permanent projection. The creation of a natural nipple with lasting three-dimensional projection remains a challenge, while the areola reconstructions are of simple execution and usually offer no difficulties. In order to optimize the results, some rules should be followed, regardless of the technique used.6

Farhadi et al.11 and Berson6 showed that, in unilateral reconstructions, the choice of technique for nipple reconstruction should be dictated by the characteristics of the contralateral nipple, and we fully agree with this hypothesis. In a previously published study17, it was verified that, in the cases of patients with very projected contralateral nipples or with very wide base, the technique that offered better results when compared to others was grafting of the contralateral nipple. In patients with poorly designed contralateral nipple, it is the quality of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that will indicate the success of the technique.

Currently, we have observed that, with the increase in reconstructions using prostheses or expanders, as shown in Table 3, the cutaneous flap donor area is increasingly scarce and, most of the time, has a scar crossed in the central part of the neo-breast, resulting in the withdrawal of the NAC in mastectomies with preservation of the skin. These two factors, in a large majority of patients, started to become a contraindication for NAC reconstruction in the second breast reconstruction, being necessary to perform fat grafting in this region to enable a future reconstruction.

The ideal technique for NAC reconstruction should allow its construction on any type of tissue, despite previous scars and radiotherapy; moreover, the limits of the new NAC should not exceed the margins of flaps used in breast reconstructions. Losken et al.13 (C-V flap), Anton et al.14 (star and wrap flaps), and Little and Dilamartine et al.16 (skate flap) presented results in accordance with these characteristics.

However, over the years, we have accompanied the loss of the outcome with increasing index of dissatisfaction by the patients. In addition, all these characteristics can still be aggravated if the patient is submitted to radiotherapy. The sum of these factors has led us to develop a technique that allowed a safe construction of the nipple.

The dermal flaps, in general, when constructed on a tense surface, tend to flatten, since there is the enlargement of the scar on the area where it was removed. Farhadi et al.11 reported that loss of nipple projection occurs due to the contraction of the wound. Thus, hypercorrection should be of ٢٥٪ to attain, in the long term, better symmetry with the contralateral nipple2,17.

The triangular cutaneous flap technique was based on the observation of the so-called “dog ear,” in which there is excess skin in an area without tension, which prevents the accommodation of this excess tissue. This skin with little dermal component reduces the shrinkage, and as we maintain the integrity of the subdermal plexus, we observed few complications related to necrosis, even with the presence of scars in this area (Table 4).

In relation to the bilateral reconstructions, the indication of the technique is based on the desire of the patient for a more or less projected nipple, again depending on the quality of the skin. If the option is for greater projection, Shestak et al.1, Shestak and Nguyen8, and Farhadi et al.11 suggest the double-opposing flap technique to construct the nipple, and we also found good results in this technique. However, in general, we have observed a preference for less projected nipples. Some patients do not feel at ease with a bulky permanent projection. In these cases, we opted the triangular cutaneous flap technique as an indication17.

Bezerra et al.18 demonstrated satisfactory late results using autologous tissue as fillers, as did Tostes et al.19, who used synthetic materials. Tanabe et al.20 and Brent and Bostwick3 used atrial cartilage to achieve better nipple projections and showed partial projection loss of 48.1% with minimal complications.

Tanabe et al.20 used bilobed and trilobed flaps in their studies and proved that bilobed flaps provide greater nipple projections, while the trilobed ones lead to higher rates of loss of projection and partial necrosis. This new technique, despite being trilobed, presented a low index of necrosis. We believe this is due to the slight thickness of the flap that remains irrigated only by the superficial dermal plexus.

A variety of these alloplastic materials are available to increase the NAC projection. However, the risks of foreign body reaction or infection and the tendency to migrate and extrude render the use these materials a challenge3.

Spears et al.15 described a three-dimensional tattooing technique in which only the tattoo is made for the reconstruction of the entire NAC and obtained good esthetic results4. In addition, the three-dimensional technique can resolve asymmetries after NAC reconstruction, without additional surgical procedures. As for the projection, an optical illusion caused by pigmentation shadowing occurs4. It is a significant advance in obtaining better esthetic results for women undergoing breast reconstruction4.

We observed a very satisfactory evaluation of patients who underwent the original triangular cutaneous flap technique. This can be due to greater care in predicting disappearance and asymmetry in comparison with other techniques. In addition, there is a tendency for low rates of complications in the donor area compared with local flaps, including distortions and flatness of the breast.

The emotional and esthetic impact in the final appearance of the reconstructed NAC is essential in breast reconstruction. While this procedure is often regarded as “small” in the patient’s mind, the result can change the fate of the entire breast reconstruction process17. Thus, the position and symmetry of the NACs are critical elements to be considered in the evaluation of the appearance of the breast after the surgery.

Poor positioning of NACs and the need for new correction surgeries are not uncommon, reaching up to 50% correction levels in published studies5. In our series, there were no cases needing surgical reassessment to correct asymmetries; however, in 5 cases, PMMA injection was used to correct distortions in the projection.

CONCLUSION

The original inverted triangular cutaneous flap technique presents the advantages of easy execution and safety in reconstruction of the NAC.

COLLABORATIONS

|

MCC |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

MCAG |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

LGM |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data. |

|

LMCD |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data. |

|

LDPB |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data. |

|

OMC |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data. |

|

BEP |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data. |

|

FTM |

Statistical analyses. |

REFERENCES

1. Shestak KC, Gabriel A, Landecker A, Peters S, Shestak A, Kim J. Assessment of long-term nipple projection: a comparison of three techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):780-6. PMID: 12172139 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000019716.27638.0D

2. Broadbent TR, Woolf RM, Metz PS. Restoring the mammary areola by a skin graft from the upper inner thigh. Br J Plast Surg. 1977;30(3):220-2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1226(77)90094-7

3. Brent B, Bostwick J. Nipple-areola reconstruction with auricular tissues. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60(3):353-61. PMID: 331365

4. Gruber RP. Nipple-areola reconstruction: a review of techniques. Clin Plast Surg. 1979;6(1):71-83.

5. Millard DR Jr, Devine J Jr, Warren WD. Breast reconstruction: a plea for saving the uninvolved nipple. Am J Surg. 1971;122(6):763-4. PMID: 5127726 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(71)90441-7

6. Berson MI. Construction of pseudoareola. Surgery. 1946;20(6):808. PMID: 20277123

7. Little JW 3rd. Nipple-areola reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1984;11(2):351-64.

8. Shestak KC, Nguyen TD. The double opposing periareola flap: a novel concept for nipple-areola reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(2):473-80. PMID: 17230078 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000246382.40806.26

9. Hammond DC, Khuthaila D, Kim J. The skate flap purse-string technique for nipple-areola complex reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(2):399-406. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000267337.08565.b3

10. Azzawi K, Humzah MD. Mammaplasty: the ‘Modified Benelli’ technique with de-epithelialisation and a double round-block suture. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(10):1068-72. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2005.11.036

11. Farhadi J, Maksvytyte GK, Schaefer DJ, Pierer G, Scheufler O. Reconstruction of the nipple-areola complex: an update. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(1):40-53. PMID: 16482789 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2005.08.006

12. Cronin ED, Humphreys DH, Ruiz-Razura A. Nipple reconstruction: the S flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81(5):783-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198805000-00026

13. Losken A, Mackay GJ, Bostwick J 3rd. Nipple reconstruction using the C-V flap technique: a long-term evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(2):361-9. PMID: 11496176 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200108000-00013

14. Anton M, Eskenazi LB, Hartrampf CR Jr. Nipple reconstruction with local flaps: star and wrap flaps. Perspect Plast Surg. 1991;5(1):67-78. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1080415

15. Spear SL, Albino FP, Al-Attar A. Classification and management of the postoperative, high-riding nipple. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(6):1413-21. PMID: 23416436 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31828bd3e0

16. Dilamartine J, Cintra Junior R, Daher JC, Cammarota CM, Galdino J, Pedroso DB, et al. Reconstrução do complexo areolopapilar com double opposing flap. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;28(2):233-40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752013000200011

17. Cammarota MC, Cosac OM, Lamartine JD, Benedik Neto A, Lima RQ, Almeida CM, et al. Avaliação de quatro técnicas de confecção de papila. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(4):538-43.

18. Bezerra FJF, Moura RMG, Costa VRS. Reconstrução papilar: preenchimento com tecido autólogo ou heterólogo. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2010;25(1):200-4.

19. Tostes ROG, Silva KDA, Andrade Júnior JCCG, Ribeiro GVC, Rodrigues RBM. Reconstrução do mamilo por meio da técnica do retalho C-V: contribuição à técnica. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2005;20(1):36-9.

20. Tanabe HY, Tai Y, Kiyokawa K, Yamauchi T. Nipple-areola reconstruction with a dermal-fat flap and rolled auricular cartilage. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(2):431-8. PMID: 9252612 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199708000-00025

1. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2. Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Brasília, DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Marcela Caetano Cammarota Quadra SMHN, Quadra 2, Bloco C, Sala 1315, Asa Norte, Brasília, DF, Brazil Zip Code: 70710-149. E-mail: almeida_mila12@yahoo.com.br

Article received: January 18, 2017.

Article accepted: January 26, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter