Original Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Primary palatoplasty using the von Langenbeck technique: surgical experience and aesthetic results of 278 cases

Palatoplastia primária pela técnica de Von Langenbeck: experiência e resultados morfológicos obtidos em 278 casos operados

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Palatoplasty with elevated bilateral mucoperiosteal flaps using the von Langenbeck technique associated with intravelar veloplasty is a common procedure with low rates of oronasal fistula (ONF) and velopharyngeal insufficiency. The objective is to present the author's surgical experience and the incidence of ONF among 278 patients who underwent primary palatoplasty using the von Langenbeck technique associated with intravelar veloplasty.

Methods: This retrospective study analyzed the medical records of 278 patients who underwent primary palatoplasty at the Mário Covas Treatment Center for Craniofacial Malformations of the Guilherme Álvaro Hospital located in the municipality of Santos, São Paulo, Brazil, between May 2010 and May 2018.

Results: A total of 278 primary palatoplasty procedures were performed; of them, 225 (80.9%) were performed in two surgical stages and 53 (19.1%) in one surgical stage. The study population included 182 men (65.5%) and 96 women (34.5%). The prevalence of left and bilateral cleft lip and palate was 26.3% and 27%, respectively, and the prevalence of bilateral cleft palate, and right cleft lip and palate was 37.4% and 7.6%, respectively. Sixty-one patients had ONF (21.94%), the incidence of which decreased progressively throughout the study period.

Conclusion: Primary palatoplasty, using the von Langenbeck technique associated with intravelar veloplasty, is reproducible when performed in one or two surgical stages, and considered safe when the learning curve is reached with a complication rate similar to those in the literature.

Keywords: Cleft palate; Oral fistula; Surgery, Plastic; Velopharyngeal insufficiency; Palate, Soft; Palate, Hard; Palatal muscles.

RESUMO

Introdução: A palatoplastia com elevação de retalhos mucoperiostais bipediculados pela técnica de Von Langenbeck associada a veloplastia intravelar é técnica mais utilizadas na atualidade apresentando na literatura baixa taxa de fístula oronasal e de insuficiência velofaríngea. O objetivo é apresentar a experiência acumulada do autor e avaliar a incidência de fístula oronasal após 278 casos de palatoplastia primária, pela técnica de Von Langenbeck associada a veloplastia intravelar.

Métodos: Estudo retrospectivo de 278 prontuários de pacientes submetidos à palatoplastia primária no Centro de Tratamento de Malformações Craniofaciais Mário Covas - Hospital Guilherme Álvaro - Santos/SP, entre de maio de 2010 a maio de 2018.

Resultados: 278 procedimentos de palatoplastia primária pela técnica relatada, 225 (80,9%) em duas etapas cirúrgicas e 53 (19,1%) em única etapa. Masculino 182 (65,5%) e feminino 96 (34,5%). Fissuras labiopalatais esquerda e bilaterais (26,3% e 27%, respetivamente). As fissuras palatais completas corresponderam a 37,4% e a fissura labiopalatal direita com 7,6%. 61 pacientes apresentaram fístula oronasal (21,94%) observando-se uma diminuição progressiva da incidência em cada período.

Conclusão: A palatoplastia primária pela técnica de Von Langenbeck associada à veloplastia intravelar é uma técnica reprodutível em uma ou duas etapas cirúrgicas e pode ser considerada segura quando alcançada uma adequada curva de aprendizado apresentando um índice de complicações acorde com a literatura mundial.

Palavras-chave: Fissura palatina; Fístula bucal; Cirurgia plástica; Insuficiência velofaríngea; Palato mole; Palato duro; Músculos palatinos

INTRODUCTION

Among the congenital craniofacial malformations, cleft lip and palate (CLP) is the most common and occurs in 1 of every 650 births in Brazil1. CLP may cause functional limitations in speech, difficulty eating and breathing, and negative social and psychological consequences during adulthood.

The palate acts as an anatomical barrier that separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity. Together with other structures of the pharynx, it contributes to the function of the velopharyngeal sphincter by assisting in speech and feeding. Without the normal function of these structures, patients with cleft palate may develop changes such as nasal air leak and food reflux through the nose2. Moreover, patients with CLP have social adaptation problems because of their physical appearance.

CLP is classified according to the affected region into pre-foramen (lips and primary palate), transforamen (primary and secondary palate), and post-foramen. Therefore, the submucosal cleft should be identified in cases of bifid uvula, and cleft palate size can be classified as narrow, normal, or wide.

The history of palatoplasty is long, dating from 17603, with significant progress in clinical research, and most techniques are based on mobilization of the axial flaps supplied by the greater palatine artery. Von Langenbeck4 (1862) described the use of bilateral mucoperiosteal flaps without reconstruction of the intravelar muscle or palatal stretching, leading to the development of the push back techniques described by Veau (1931)5 and Wardill and Killner (1937)6,7.

Repair of the soft palate requires dissection of the palatal muscles and repositioning of the levator veli palatini muscle with or without manipulation of the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches and tensor veli palatini muscle for reconstructing the muscle sheath8. Braithwaite9 (1964) and Kriens10 (1969) defined “intravelar veloplasty” as the rotation and terminoterminal anastomosis of the levator veli palatini muscle to the tensor veli palatini muscles to improve the functional results of palatoplasty11. This technique was modified by Cutting et al.12 (1995) and Sommerlad et al.13 (2002). Furlow Junior14 (1986) described double-opposing Z-palatoplasty and found that it achieved good functional results in the nasal and oral lining with lower rates of velopharyngeal insufficiency (VFI).

Regardless of the technique used, the objectives of palatoplasty are to: 1) Stretch the palate to minimize the incidence of VFI and promote adequate speech development; 2) Minimize the restriction of maxillary and alveolar growth; and 3) Prevent complications, including oronasal fistulas (ONFs).

OBJECTIVE

To present the author’s experience and the incidence of ONF in 278 cases of primary palatoplasty using the von Langenbeck technique associated with intravelar veloplasty.

METHODS

This retrospective study reviewed the medical records of all patients treated surgically at the Mário Covas Treatment Center for Craniofacial Malformations, Guilherme Álvaro Hospital, Santos, São Paulo, Brazil, between May 2010 and May 2018.

The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of cleft palate (CP) or CLP associated or not with syndromes (excluding cases of cleft soft palate) and treated with primary palatoplasty using the described technique performed by the same surgeon (the author).

A total of 278 records were selected, and the following data were obtained:

Diagnosis: right, left, or bilateral CLP corresponding to trans-foramen clefts; and bilateral CP, corresponding to post-foramen clefts;

Sex (male/female)

Race (Caucasian, mixed, or Black);

Patient age (in months) at the time of primary palatoplasty;

Surgical stage of primary palatoplasty (one or two);

Clinical course with ONF (yes/no) during the 6-month follow-up period after the last procedure.

The data collected over the 8-year study period (May 2010 to May 2018) were organized and recorded in an Excel spreadsheet, and the data on the appearance of ONF were analyzed in eight 1-year periods based on the date of the last surgery.

Phonation results were not included in the analysis because the objective of this study was to evaluate the aesthetic results and the incidence of ONF.

RESULTS

A total of 278 primary palatoplasty procedures using the von Langenbeck technique associated with intravelar veloplasty were evaluated, including 225 (80.9%) performed in two surgical stages (soft palate first, followed by hard palate) and 53 (19.1%) performed in one surgical stage.

The study population included 182 (65.5%) men and 96 (34.5%) women.

In preoperative diagnoses, the incidence of left and bilateral CLP was 26.3% and 27%, respectively, while that of complete CP and right CLP was 37.4% and 7.6%, respectively. A total of 157 patients (56.4%) were Caucasian, 107 (38.4%) were mixed, and 14 (5.04%) were Black. The average age at the time of primary palatoplasty was 17.2 months.

Postoperative complications included total suture dehiscence (2 cases [0.7%]), postoperative bleeding (4 cases [1.44%]), and infection (2 cases [0.72%]). There were no cases of flap necrosis.

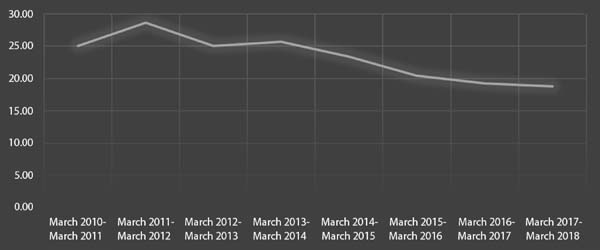

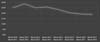

ONF occurred in 61 patients (21.94%) during the study period, and the incidence decreased progressively. The incidence of ONF in the first 1-year period (May 2010 to May 2011) and the last 1-year period (May 2017 to May 2018) was 25.00% and 18.75%, respectively (Table 1).

| Period | Patients | Fistula | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| May 2010 - May 2011 | 4 | 1 | 25.00 |

| May 2011 - May 2012 | 7 | 2 | 28.57 |

| May 2012 - May 2013 | 36 | 9 | 25.00 |

| May 2013 - May 2014 | 35 | 9 | 25.71 |

| May 2014 - May 2015 | 47 | 11 | 23.40 |

| May 2015 - May 2016 | 49 | 10 | 20.41 |

| May 2016 - May 2017 | 52 | 10 | 10.23 |

| May 2017 - May 2018 | 48 | 9 | 18.75 |

| Total | 278 | 61 | 21.94 |

Data on ONF for the primary and secondary palates were included in the study, although their site of occurrence was not determined.

Surgical technique

Patients undergoing primary palatoplasty are treated surgically at 6–18 months of age depending on the ease of follow-up. In cases of trans-foramen clefts, primary cheiloplasty is performed in patients older than 3 months and primary palatoplasty can be performed 6 months later using the von Langenbeck technique with or without a vomer flap. Cheiloplasty was not performed together with primary palatoplasty in this population.

CP type was classified as narrow, normal, or wide; in narrow clefts, the procedure was performed in one surgical stage, while in normal or wide clefts, it was performed in two stages (soft palate first, hard palate 6 months later).

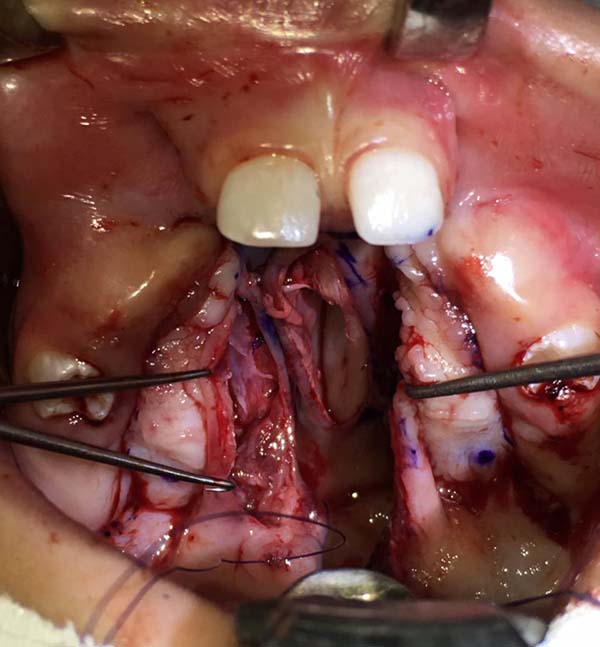

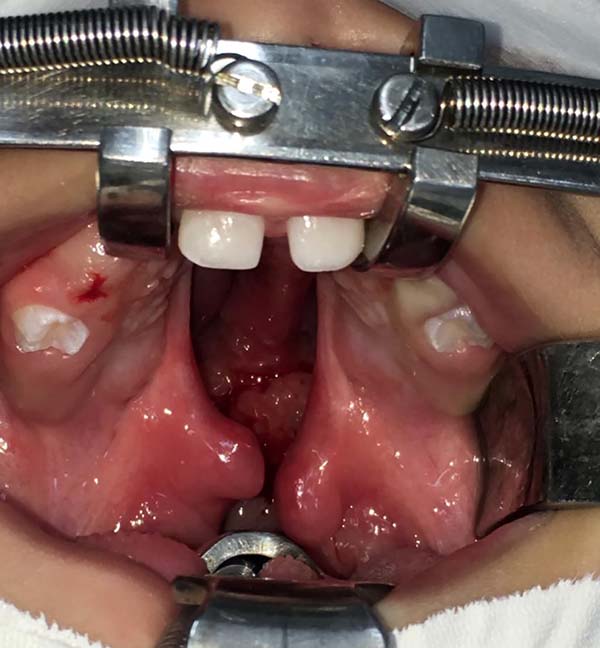

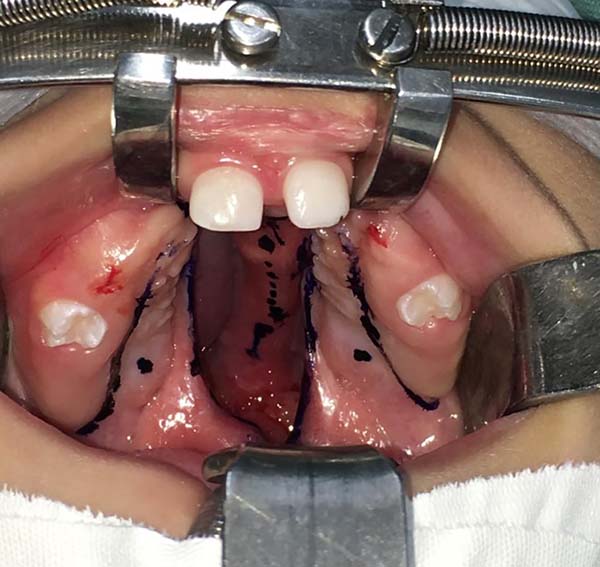

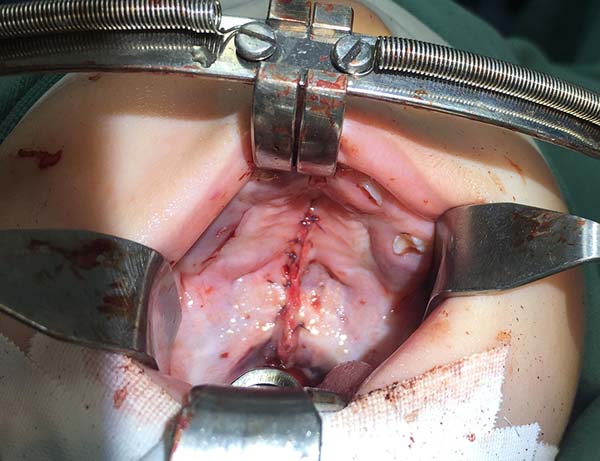

All patients underwent surgery while under general anesthesia and orotracheal intubation under direct vision. A Dingman mouth gag was positioned after adequate visual inspection (Figure 1).

The edges of the cleft were demarcated on the soft palate, which was infiltrated with 2% lidocaine combined with a vasoconstrictor (1: 200,000) for topical anesthesia. An incision was made on the edges, and the plane of the oral and nasal mucosa was dissected to release the anterior insertion of the levator veli palatini muscle bilaterally and, if necessary, the insertion of the tensor veli palatini muscle. The nasal mucosa was closed and the cleft uvula was repaired. The levator veli palatini muscle was closed and sutured with U-shaped Vicryl® 4-0 sutures, while the oral mucosa was sutured with U-shaped Vicryl® 5-0 sutures.

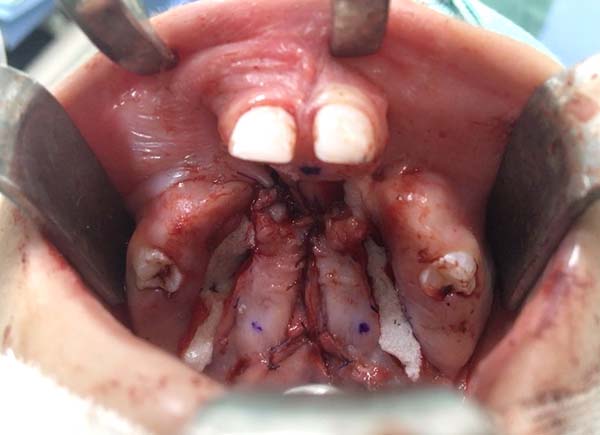

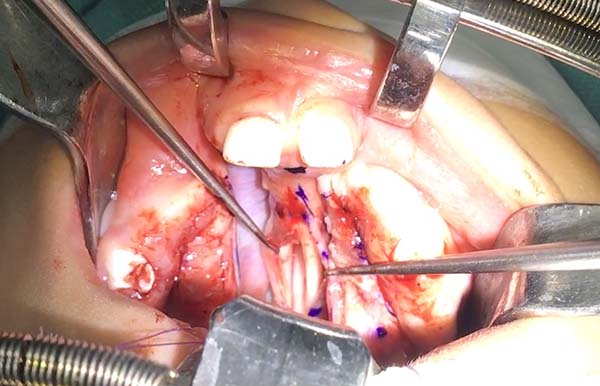

Relaxing incisions and vomer flaps were demarcated in the second surgical stage (Figure 2), and the incision sites and hard palate were infiltrated with 2% lidocaine combined with a vasoconstrictor (1: 200,000) for topical anesthesia.

Bilateral relaxing incisions were made on the medial hard palate at the alveolar crest according to the von Langenbeck procedure.

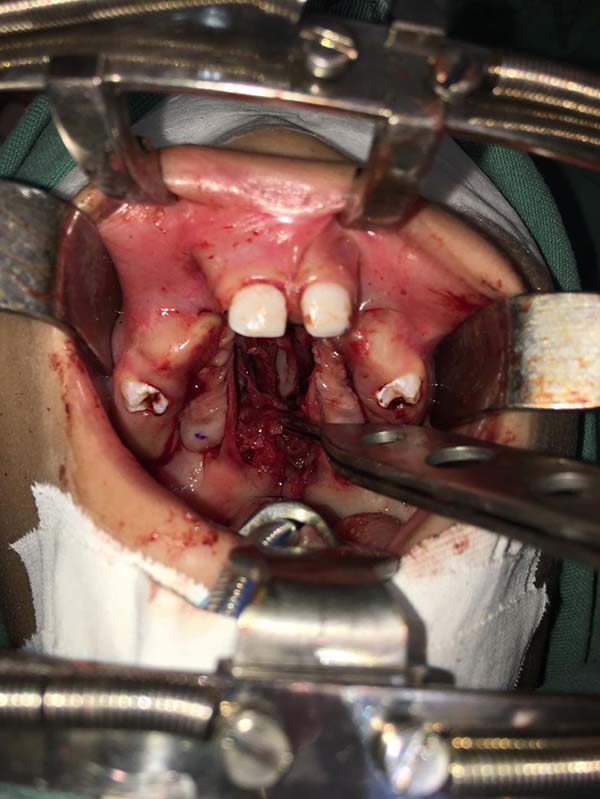

The bilateral mucoperiosteal flaps were elevated, the pedicle of the greater palatal artery was identified, and the nasal mucosa of the hard palate was dissected (Figure 3).

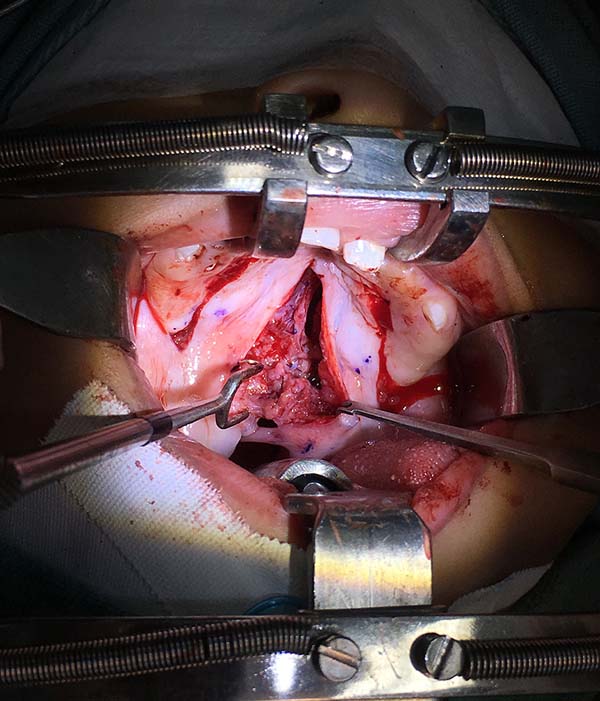

In wide and normal clefts, unilateral or bilateral mucoperiosteal flaps of the vomer were elevated to close the nasal lining (Figures 4 and 5).

The mucoperiosteal flaps were closed, and the oral mucosa was sutured with U-shaped Vicryl 5-0 sutures (Figures 6 and 7).

Hemostatic dressings remained at the site of the relaxing incisions only in cases in which the open area was large because they did not impair healing, although they had no demonstrable benefit (Figures 8 and 9).

The steps mentioned above were performed simultaneously in cases of primary palatoplasty in a single surgical step.

DISCUSSION

The controversial aspects of palatoplasty include the ideal age at the time of primary surgery to interfere as little as possible with facial growth and allow adequate speech development.

CLP affects facial bone growth, allowing the development of trends and different protocols for its repair as well as surgical repair in one or two surgical stages15,16 without affecting mandibular growth17.

There is no consensus on the ideal age for primary palatoplasty. In our protocol, this surgery was performed at the age of 6–18 months in one stage or alternatively one stage for narrow clefts and two stages for normal and wide clefts.

Despite being the oldest technique, von Langenbeck’s palatoplasty is still used and a good option for wide and incomplete clefts because it is simple and facilitates dissection18,19. Palatoplasty combined with repair of the nasal lining and muscle sheath is safe and has a low rate of ONF20. The occurrence of ONF depends on patient age21, cleft type and extent22, association with syndromes23, surgeon experience, and factors that affect the surgical outcome including suture tension, bleeding, and infection20.

The incidence of ONF depends on surgical timing, and the primary surgery can be delayed because of the limited access to health services as demonstrated in our sample by the significant difference in patient age at the time of the first surgery. Surgeon experience also plays a fundamental role given that the author’s learning curve improved over time (Figure 10). The sample was evaluated in eight 1-year periods from May 2010 to May 2018. The incidence of ONF in the first and last periods was 25% and 18.75%, respectively, and the average incidence throughout the study period was 21.94%, which agrees with data in the literature. It should be noted that all ONFs present at 6 months postoperative were identified, including those located anterior to the incisive foramen given that some studies disregarded them.

The reported incidence of ONF is 0–60%, and the incidence in Brazil is 15.3%24.

ONF can be classified as symptomatic or non-symptomatic; the former does not always require surgical management. However, in this case series, all ONFs located posterior to the incisor foramen were operated upon at 6 months after definitive surgery using different techniques according to their size and location because their description is beyond the scope of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

Primary palatoplasty using the von Langenbeck technique associated with intravelar veloplasty was reproducible in our service when performed in one or two surgical stages. Although the incidence of ONF was higher than that reported in the literature, this surgical procedure is considered safe when the learning curve is reached and improves the aesthetics of CP.

COLLABORATIONS

|

MRM |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

CGM |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation |

|

LG |

Conception and design study, Methodology, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation |

|

ACC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Methodology, Realization of operations and/or trials |

|

AOE |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation |

|

OS |

Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation |

REFERENCES

1. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Fissura labiopalatal. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2017. Disponível em: http://portalms.saude.gov.br/atencao-especializada-e-hospitalar/especialidades/cirurgia-plastica-reparadora/fissura-labiopalatal

2. Mélega JM, Camargos AG. Fissuras de lábio e palato. In: Mélega JM, Zanini AS, Psillakis JM, editores. Cirurgia plástica: reparadora e estética. 2ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: MEDSI; 1992. p. 247-60.

3. Rogers BO. Cleft palate surgery prior to 1816. In: Frank McDowell, organizer. The source book of plastic surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1977. p. 180-3.

4. Von Langenbeck B. Die uranoplastik mittles ablosung des microsperiostalen gaumenüberzuges. Arch Klin Chir. 1862;2:205.

5. Veau V. Division palatine. Paris: Masson; 1931.

6. Wardill WEM. Technique of operation for cleft lip and palate. Br J Surg. 1937;25(97):117-30.

7. Kilner TP. Cleft lip and palate repair technique. St. Thomas Hosp Report. 1937;2:127.

8. Chepla KJ, Gosain AK. Evidence-based medicine: cleft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(6):1644-8.

9. Braithwaite F. Cleft palate repair. In: Gibson T, editor. Modern trends in plastic surgery. London: Butterworths; 1964. p. 30-49.

10. Kriens OB. An anatomical approach to veloplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;43(1):29-41.

11. Gugliano C. Fisura de paladar. In: Monasterio L, editor. En tratamiento interdisciplinario de las fisuras labiopalatinas. 2008; p. 363-78.

12. Cutting CB, Rosenbaum J, Rovati L. The technique of muscle repair in the cleft soft palate. Oper Tech Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;2:215-22.

13. Sommerlad BC, Mehendale FV, Birch MJ, Sell D, Hattee C, Harland K. Palate re-repair revisited. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2002;39(3):295-307.

14. Furlow Junior LT. Cleft palate repair by double opposing Z-plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78(6):724-38.

15. Del Guercio F, Meazzini MC, Garattini G, Morabito A, Semb G, Brusati R. A cephalometric intercentre comparison of patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate at 5 and 10 years of age. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32(1):24-7.

16. Hortis-Dzierzbicka M, Radkowska E, Stecko E, Dudzinski L, Fudalej PS. Speech outcome in complete unilateral cleft lip and palate - a comparison of three methods of the hard palate closure. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(11):809-15.

17. Silva Filho OG, Normando AD, Capelozza Filho L. Mandibular morphology and spatial position in patients with clefts: intrinsic or iatrogenic?. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1992;29(4):369-75.

18. Lindsay WK. Von Langenbeck palatoplasty. In: Grabb WC, Rosenstein FW, Bzoch KR, editors. Cleft lip and palate. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1971. p. 393-403.

19. Billmire DA. Surgical management of clefts and velopharyngeal dysfunction. In: Kummer AW, editor. Cleft palate and craniofacial anomalies: effects on speech and resonance. Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning; 2008. p. 401-24.

20. Williams WN, William N, Seagle M, Pegorato-Krook MI, Souza TV, Garla L, et al. Prospective clinical trial comparing outcome measures between Furlow and von Langenbeck Palatoplasties for UCLP. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66(2):154-63.

21. Emory Junior RE, Clay RP, Bite U, Jackson IT. Fistula formation after palatal closure: an institutional perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(6):1535-8.

22. Muzaffar AR, Byrd HS, Rohrich RJ, Johns DF, LeBlanc D, Beran SJ, et al. Incidence of cleft palate fistula: an institutional experience with two-stage palatal repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1515-8.

23. Bresnick S, Walker J, Clarke-Sheehan N, Reinisch J. Increased fistula risk following palatoplasty in Treacher Collins syndrome. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2003;40(3):280-3.

24. Baptista EVP, Salgado IV, Pereira R. Incidência de fístula oronasal após palatoplastias. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plást. 2005;20(1):26-9.

1. Serviço de Cirurgia Plástica Osvaldo Saldanha, Universidade Metropolitana de Santos,

Santos, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Carlos Goyeneche Montoya Avenida Ana Costa, 146, Conj. 1201, Santos, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 11060-002. E-mail: carlosgoye.m@gmail.com

Article received: February 22, 2019.

Article accepted: October 21, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter