Original Article - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Anatomical mapping of vascular anomalies of the lips

Mapeamento anatômico das anomalias vasculares dos lábios

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The lip is the body region more often affected by vascular anomalies (VAs). Identifying the appropriate etiology of the lesion is significantly important when determining the treatment of choice for the patient. This study aimed to determine the association between the anatomical positioning and the characteristics of the lesions and the etiological diagnosis of VAs of the lips to identify the appropriate tool to be used in clinical practice.

Methods: A retrospective analysis was performed in 150 patients with VA of the lips evaluated between 1999 and 2017. The etiological diagnosis was based on the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies 2014 classification. Clinical and photographic analysis was performed to assess the anatomical pattern of involvement and map the lesions.

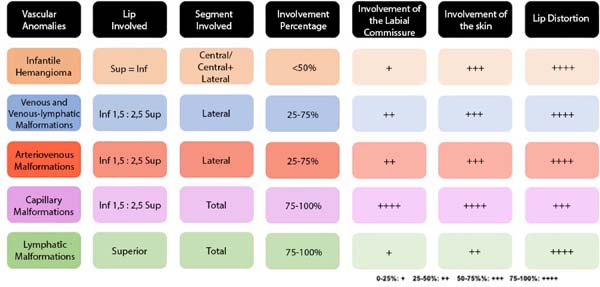

Results: An infantile hemangioma was observed to a lesser extent in only one lip and was situated more centrally, with rare involvement of the labial commissure. Venous and venous-lymphatic malformations and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) involving the upper lip were predominantly located more laterally and caused significant deformity. However, AVMs more often extended beyond the limits of the vermilion. Capillary malformations were observed in the entire lower lip in some patients. Simple lymphatic malformations were observed in the entire upper lip with significant distortion in some patients.

Conclusion: The initial presentation of VAs often comprises minimal changes; hence, establishing an assertive diagnosis is considered difficult. Specific patterns of involvement were observed for each etiological diagnosis studied. Anatomical mapping can be used as an auxiliary diagnostic tool and can possibly identify an appropriate clinical intervention in patients with VAs of the lip.

Keywords: Hemangioma; Lip; Multiple abnormalities; Vascular tissue tumors; Congenital abnormalities.

RESUMO

Introdução: O lábio é a região do corpo mais frequentemente acometida por anomalias vasculares (AV). A correta determinação da etiologia da lesão é determinante à escolha do tratamento do paciente e à correta condução do caso. O objetivo deste estudo é correlacionar o posicionamento anatômico e as características das lesões com o diagnóstico etiológico das AVs dos lábios, a fim de promover uma ferramenta que auxilie na prática clínica.

Métodos: Análise retrospectiva de 150 pacientes com AV dos lábios, avaliados entre 1999 e 2017. O diagnóstico etiológico foi baseado na classificação de ISSVA 2014. Análise clínica e fotográfica foi realizada para avaliar o padrão anatômico de envolvimento e mapear as lesões.

Resultados: Hemangioma infantil apresentou acometimento de apenas um lábio, em menor extensão e situado mais centralmente, com raro envolvimento de comissura oral. Malformações venosas e venolinfáticas (MVs) e malformações arteriovenosas (MAVs) envolveram o lábio superior predominantemente, situadas mais lateralmente e acarretando significativa deformidade. Contudo, MAVs apresentaram mais frequente extensão além dos limites do vermelhão. Os pacientes com malformações capilares (MCs) sofriam de acometimento integral do lábio inferior. Todos os casos de malformações linfáticas exclusivas (MLs) envolveram o lábio superior inteiro, com grande distorção.

Conclusão: A apresentação inicial das AVs muitas vezes consiste em pequenas alterações, desafiadoras ao diagnóstico assertivo. Padrões específicos de acometimentos foram observados para cada diagnóstico etiológico estudado. O mapeamento pode ser utilizado como ferramenta auxiliar diagnóstica e contribuir para melhor intervenção nos pacientes com anomalias vasculares labiais.

Palavras-chave: Hemangioma; Lábio; Anormalidades múltiplas; Neoplasias de tecido vascular; Anormalidades congênitas

INTRODUCTION

According to the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification, vascular anomalies (VAs) are categorized into the following two main groups: tumors and malformations. Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor, while congenital malformations are defined according to the presence of a venous, lymphatic, arteriovenous, and capillary component or the combination thereof1-5. For the past years, the consensus on the terminology and classification of these lesions was unclear, with negative clinical outcomes on the therapeutic strategies performed, which were often applied in a heterogeneous and nonparameterized manner, increasing the iatrogenic effects of these lesions. After the standardization of the ISSVA, different treatment options were compared, and each etiological diagnosis was associated with a gold standard procedure. The diagnosis of a VA is essentially clinical and is based on anamnesis and careful physical examination. Radiological examinations are required in selected situations3,6.

VAs are the most common congenital abnormalities of the soft tissues, affecting up to 10% of newborns. They are observed in any region of the body, but are more common in the head and neck than in the extremities. The lips are the body region most frequently affected by VAs 5,7,8. Considering their central position on the face, they are particularly visible, which creates a significant esthetic stigma, which tends to worsen as the patient grows. Additionally, VAs can potentially involve the oral muscles, resulting in functional problems, such as improper speech, oral incontinence, and impairment in facial mimicry5,7,9.

The pattern of involvement in the lip can be related to the etiology of the lesion, but only few studies have been conducted confirming this hypothesis7,10,11. Based on a large number of cases, this study aims at evaluating this association, contributing to a better diagnosis and management of patients with VAs of the lips.

METHODS

This was a case series conducted between 1997 and 2017 in a single Vascular Anomalies Service in São Paulo, Brazil. The present study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (protocol number 1.630.646), and patients’ parents or guardians provided informed consent for inclusion in the study.

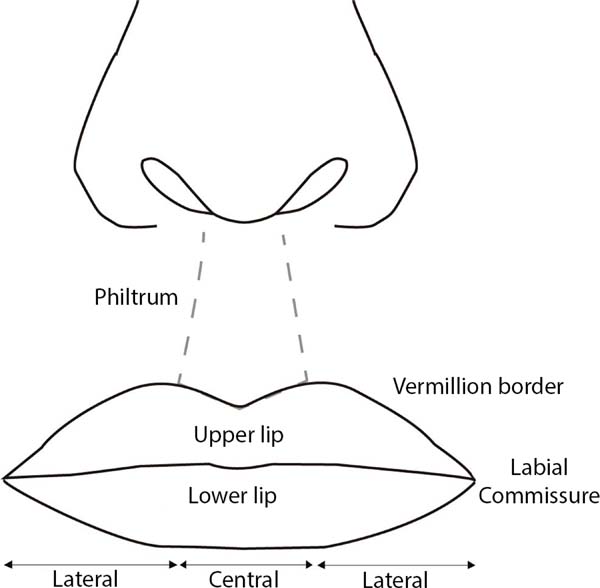

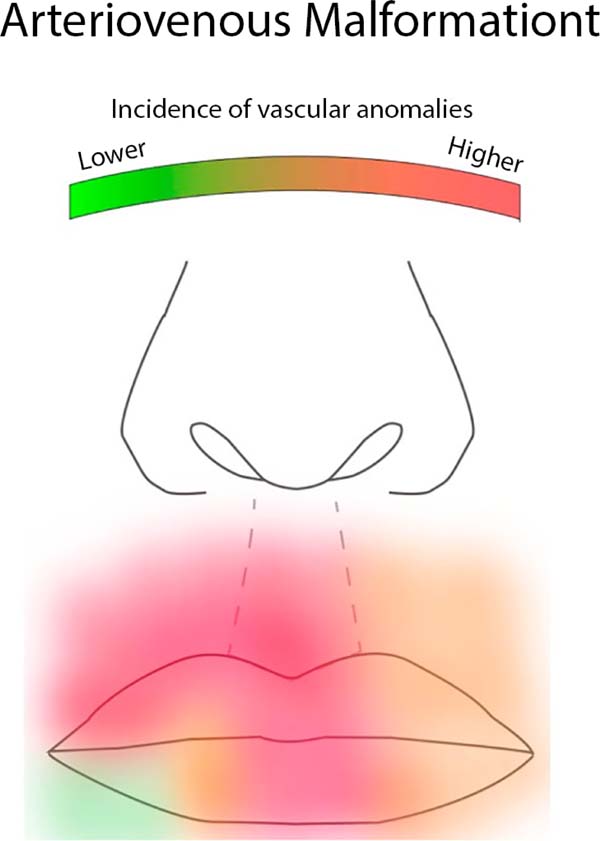

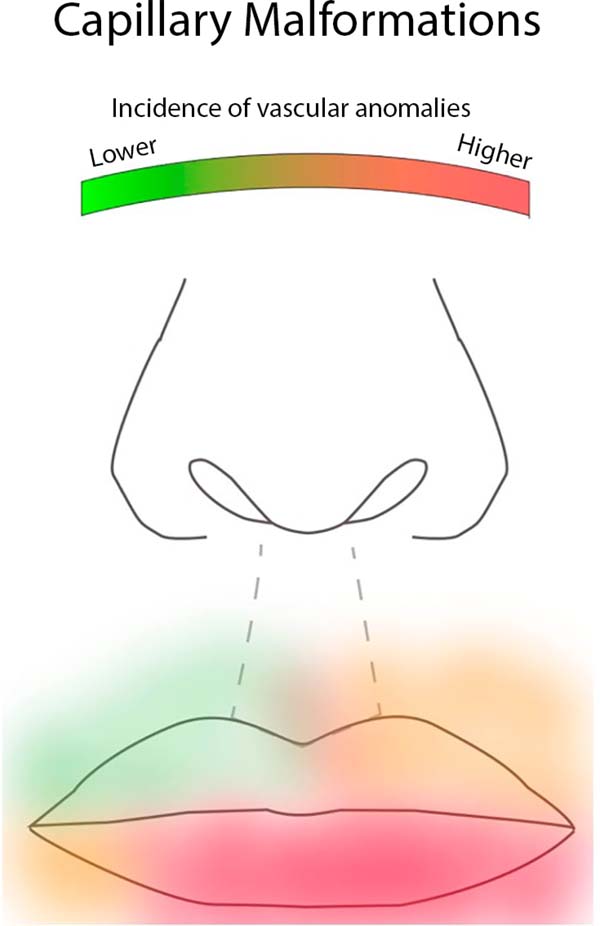

A total of 150 patients with VAs of the lips were included and evaluated by photographic analysis. Based on the ISSVA 2018 classification, the etiological diagnosis was defined by clinical evaluation, complementary tests, and biopsies, as needed. The following data were collected: type of VA, age, sex, lip involved (top/bottom/both), involvement of the labial commissure (central, lateral, central side, whole), extension (25% to 100%), involvement beyond the vermillion, and distortion of the lips (Figure 1). To compare the prevalence of IH, patients were divided by age into the following two groups: patients aged less than 7 years and patients aged greater than 7 years. An anatomical mapping of the lesions was performed, and the association between the lesions and the etiological diagnosis was assessed. The individual values were established to create heat maps for better visualization. Warmer colors represented the areas of higher incidence of the vascular anomaly represented.

The data were grouped using MS Office 2013 and analyzed using the Statistical Package International Business Machines Corporation Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 2–3.0. The likelihood ratio test was used, with a significance level of 5% (0.050).

RESULTS

A total of 150 patients (95, women; 55, men) were included in the study. Of these, 76 were diagnosed with IH, 35 with venous and venous-lymphatic malformations (VMs), 20 with arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), 16 with capillary malformations (CMs), and 3 with simple lymphatic malformations (LMs). A female predominance was related to a higher prevalence of IH (60% of 95 patients, female to male ratio = 1.7:1). Other vascular tumors in addition to IH were not observed. The results are shown in Table 1 and summarized in Figure 2.

| Affected lip | IH | VM | AVM | CM | LM | Total | |||||

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | |

| Upper | 38 | 46.91 | 23 | 28.40 | 13 | 16.05 | 4 | 4.94 | 3 | 3.70 | 81 |

| Lower | 38 | 55.88 | 12 | 17.65 | 7 | 10.29 | 11 | 16.18 | 0 | 0.00 | 68 |

| Both | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 100.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Total | 76 | 50.67 | 35 | 23.33 | 20 | 13.33 | 16 | 10.67 | 3 | 2.00 | 150 |

| Location | IH | VM | AVM | CM | LM | Total | |||||

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | |

| Central | 25 | 83.33 | 5 | 16.67 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 30 |

| Lateral | 16 | 45.71 | 13 | 37.14 | 6 | 17.14 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 35 |

| C+L | 26 | 42.62 | 17 | 27.87 | 13 | 21.31 | 4 | 6.56 | 1 | 1.64 | 61 |

| Whole | 9 | 37.50 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 4.17 | 12 | 50.00 | 2 | 8.33 | 24 |

| Total | 76 | 50.67 | 35 | 23.33 | 20 | 13.33 | 16 | 10.67 | 3 | 2.00 | 150 |

| Involvement of the labial commissure |

IH | VM | AVM | CM | LM | Total | |||||

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | |

| Yes | 7 | 15.91 | 13 | 29.55 | 9 | 20.45 | 15 | 34.09 | 0 | 0.00 | 44 |

| No | 69 | 65.09 | 22 | 20.75 | 11 | 10.38 | 1 | 0.94 | 3 | 2.83 | 106 |

| Total | 76 | 50.67 | 35 | 23.33 | 20 | 13.33 | 16 | 10.67 | 3 | 2.00 | 150 |

| Extension | IH | VM | AVM | CM | LM | Total | |||||

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | |

| < 25% | 31 | 63.27 | 13 | 26.53 | 5 | 10.20 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 49 |

| 25%-50% | 27 | 56.25 | 10 | 20.83 | 8 | 16.67 | 3 | 6.25 | 0 | 0.00 | 48 |

| > 75% | 9 | 31.03 | 12 | 41.38 | 6 | 20.69 | 1 | 3.45 | 1 | 3.45 | 29 |

| 100% | 9 | 37.50 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 4.17 | 12 | 50.00 | 2 | 8.33 | 24 |

| Total | 76 | 50.67 | 35 | 23.33 | 20 | 13.33 | 16 | 10.67 | 3 | 2.00 | 150 |

| Involvement of the skin |

IH | VM | AVM | CM | LM | Total | |||||

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | |

| Yes | 53 | 51.46 | 19 | 18.45 | 15 | 14.56 | 15 | 14.56 | 1 | 0.97 | 103 |

| No | 23 | 48.94 | 16 | 34.04 | 5 | 10.64 | 1 | 2.13 | 2 | 4.26 | 47 |

| Total | 76 | 50.67 | 35 | 23.33 | 20 | 13.33 | 16 | 10.67 | 3 | 2.00 | 150 |

| Distortion | IH | VM | AVM | CM | LM | Total | |||||

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | |

| Yes | 62 | 48.44 | 32 | 25.00 | 19 | 14.84 | 12 | 9.38 | 3 | 2.34 | 128 |

| No | 14 | 63.64 | 3 | 13.64 | 1 | 4.55 | 4 | 18.18 | 0 | 0.00 | 22 |

| Total | 76 | 50.67 | 35 | 23.33 | 20 | 13.33 | 16 | 10.67 | 3 | 2.00 | 150 |

Regarding the distribution per age group, 82 patients (54%) were younger than 7 years. Within this subgroup, 79% of the patients were diagnosed with IH. Vascular malformations were more prevalent in patients aged greater than 7 years (71.4% of VMs, 85% of AVMs, and 87.5% of CMs).

VAs were observed in both lips, but they were slightly more frequent in the upper lip (54%) than in the lower lip. The majority of patients (64.6%) presented with involvement of up to 50% extension of the lip. The most commonly affected was the center-lateral portion (40.6%), followed by the involvement of the lateral portion of the lip alone (23.3%). The involvement of the commissure was observed in 29.33% of patients. The involvement of the skin, that is, beyond the vermillion, was observed in 68.6% of patients. A distortion of the lip was observed in 85.33% of patients.

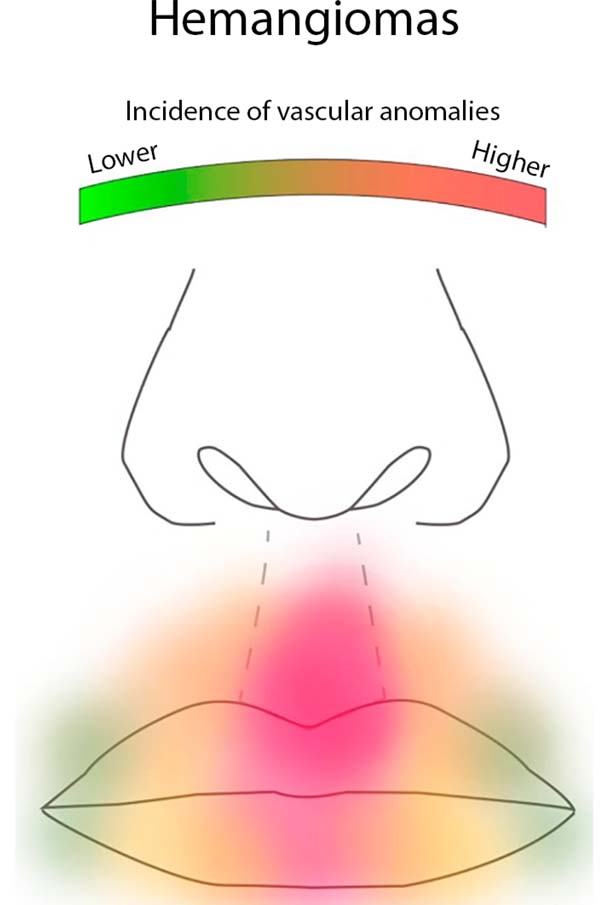

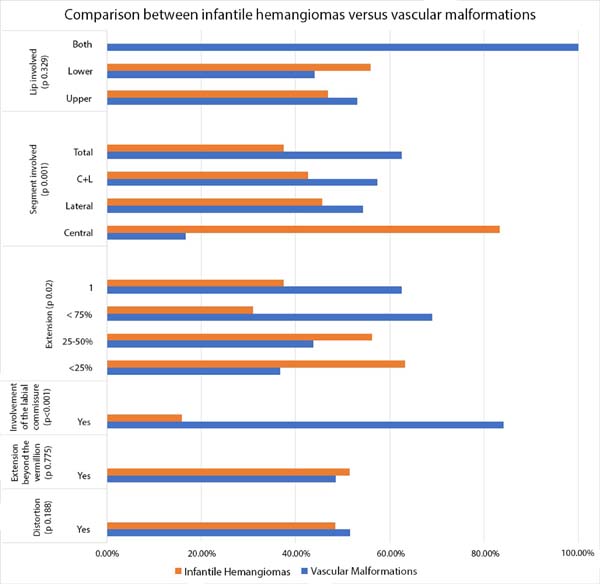

Considering only the group of vascular tumors, 85% of the patients were aged younger than 7 years. The pattern of involvement for IH was of only one lip, equally distributed between the upper and lower lip. The majority of the deformities caused lip distortion and extension beyond the vermillion. Some differences were observed between the upper and lower lip: in the upper lip, the lesions were often smaller and more centrally located compared to the lower lip, while the lower lip showed a higher degree of heterogeneity than the upper lip. Older patients were diagnosed with IH in the involuted phase. The pattern of involvement of IH is presented in Table 1 and summarized in Figure 3.

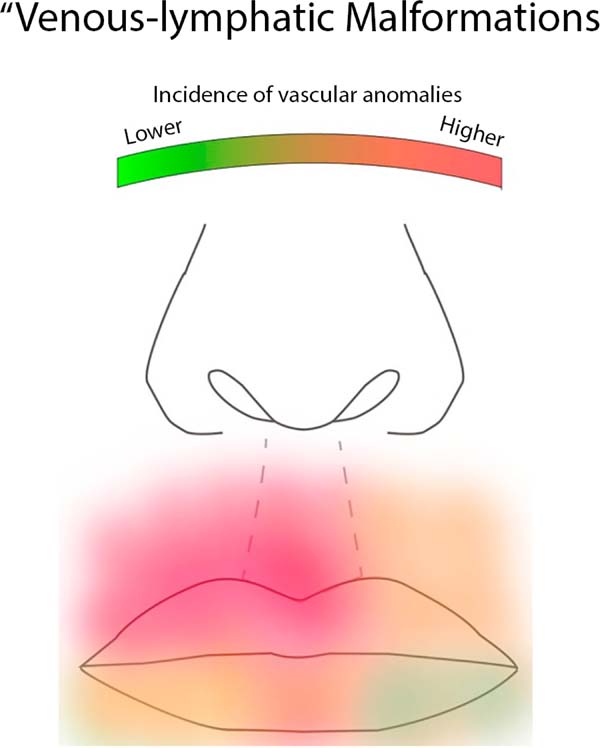

Different patterns were observed for each specific etiology of vascular malformations. Most patients were aged older than 7 years (77%). VMs were predominantly observed in the upper lip and were located more laterally. An impairment of 25% to 75% due to lip extension was observed, with significant deformity of its structure. Almost half of the patients had malformations that extended beyond the edges of the vermilion. Table 1 presents the data, and Figure 4 summarizes the pattern of involvement of VMs.

The AVMs were slightly more frequent in the upper lip than in the lower lip. The center-lateral portion of the lip was affected in the majority of patients, from 25% to 75% of their extension. A frequent involvement of the labial commissure and lip distortion were observed. The majority of the AVMs extended beyond the limit of the vermilion. The anatomical pattern is described in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 5.

CMs predominantly affected the lower lip. All patients had full involvement of the lip, and 75% of the patients presented volume distortion (Figure 6). LMs involving the upper lip were observed in only three patients, with almost full extension and large distortion.

Some statistically significant differences were observed when comparing the tumors to the vascular malformations. The IHs were located more centrally (p=0.001), with rare involvement of the labial commissure (p=0.001), and were smaller than the vascular malformations (p=0.02). These results are shown in Figure 7.

DISCUSSION

More than two-thirds of VAs are found in the head and neck region. When one considers the lips as a single unit, this region of the body has the highest prevalence of VAs5,7. A proper diagnosis is crucial for the proper management of patients to minimize the esthetic and functional impairment caused by VAs5,6,7. In clinical practice, treatment of VAs is often performed by nonspecialists. Consequently, any medical tool that assists in the differential diagnosis will allow for a faster referral to specialized healthcare professionals, resulting in a better management for patients with VAs.

The anatomical location may assist in the definition of the etiology of a VA. The treatment of VAs differs considerably in accordance with the established diagnosis. If an expectant management is preferred in vascular tumors such as IH, insufficient treatment of vascular malformations allows its expansion, deforming the location and resulting in a remarkable increase in the difficulty of treatment12,13,14. Currently, pharmacological treatment is particularly important in the treatment of VAs, and the therapeutic choice is specific for each etiology15.

The surgical resection of VA of the lips can be one treatment option. The anatomical site is crucial when planning the procedure. Reconstruction after the resection aims at correcting contour deformities, rebuilding the labial commissure, and restoring the competence of the lips. The type of resection (complete or partial) and the prospect of recurrence of the lesion also depend on the etiological type of lesion13.

This study revealed the anatomical pattern of involvement of the VAs of the lips and, more intensively, its association with the etiological diagnosis (Figure 2). The initial presentation of VAs often comprises minimal changes; hence, establishing an assertive diagnosis is considered difficult. Accordingly, the anatomical pattern of involvement is considered beneficial, specifically in mixed malformations where a profound component of the lesion can be neglected. Thus, the combination of clinical characteristics and anatomical location potentially reduces the diagnostic error and results in better treatment 14,15.

The use of images to summarize clinical concepts is gradually accepted in modern medicine. Heat maps are often used to represent complex statistical data. In this study, they were used to reveal the complex distribution of VAs in a concise and practical manner16.

Although there are some limitations in this study, such as the retrospective pattern of data collection, an anatomical pattern of distribution can be identified. The main goal was achieved and is expected to minimize the diagnostic error, with a rapid referral of the patient to an appropriate treatment.

CONCLUSION

Anatomical patterns of involvement of the lips were identified for each vascular anomaly. Thus, a tool was created to assist in the diagnosis of patients and to provide better therapeutic management.

COLLABORATIONS

|

RFZ |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Project Administration, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

DCG |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Final manuscript approval, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

AK |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Realization of operations and/or trials |

|

EMC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval |

|

RG |

Final manuscript approval, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing |

REFERENCES

1. Corrêa PH, Nunes LCC, Johann ACBR, Aguiar MCF de, Gomez RS, Mesquita RA. Prevalence of oral hemangioma, vascular malformation and varix in a Brazilian population. Braz Oral Res. 2007;21(1):40-5.

2. Mulliken JB Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(3):412-22.

3. Goldenberg DC, Hiraki PY, Marques TM, Koga A, Gemperli R. Surgical treatment of facial infantile hemangiomas: an analysis based on tumor characteristics and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(4):1221-31.

4. International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA). Classification for vascular anomalies - overview table. In: 20th ISSVA Congress Workshop; 2014 apr 1-4; Melbourne, Austrália. Melbourne, Austrália: ISSVA; 2014. Available from: http://www.issva.org/UserFiles/file/Classifications-2014-Final.pdf

5. Sohail M, Bashir MM, Ansari HH, Khan FA, Assumame N, Awan NU, et al. Outcome of management of vascular malformations of lip. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(6):e520-4.

6. Jackson IT, Carreño R, Potparic Z, Hussain K. Hemangiomas, vascular malformations, and lymphovenous malformations: classification and methods of treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91(7):126-30.

7. Ryu JY, Lee JS, Lee JW, Choi KY, Yang JD, Cho BC, et al. Clinical approaches to vascular anomalies of the lip. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(6):709-15.

8. Jafarian M, Dehghani N, Shams S, Esmaeelinejad M, Aghdashi F. Comprehensive treatment of upper lip arteriovenous malformation. J Maxillofac Oral Surg [Internet]. 2016; 15(3):394-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27752213

9. Yanes DA, Pearson GD, Witman PM. Infantile hemangiomas of the lip: patterns, outcomes, and implications. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(5):511-7.

10. Low DW. Management of adult facial vascular anomalies. Facial Plast Surg. 2003;19(1):113-29.

11. Min-Jung TO, Scheuermann-Poley C, Tan M, Waner M. Distribution, clinical characteristics, and surgical treatment of lip infantile hemangiomas. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15(4):292-304.

12. Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(12):1567-76.

13. Hiraki PY, Goldenberg DC. Diagnóstico e tratamento do hemangioma infantil. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 1983;25(2):388-97.

14. Van Doorne L, De Maeseneer M, Stricker C, Vanrensbergen R, Stricker M. Diagnosis and treatment of vascular lesion of the lip. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40(6):497-503.

15. Waner M, North PE, Scherer KA, Frieden IJ, Waner A, Mihm Junior MC, et al. The nonrandom distribution of facial hemangiomas. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(7):869-75.

16. Wilkinson L, Michael F. The history of the cluster heat map. Am Stat. 2009;63(2):179-84.

1. Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da USP, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Dov Charles Goldenberg Rua Arminda, 93, Itaim Bibi, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 04538-100. E-mail: drdov@terra.com.br

Article received: July 1, 2019.

Article accepted: October 21, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter