Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Treatment of leprosy-induced plantar ulcers

Tratamento da úlcera plantar devido à hanseníase

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Leprosy-induced plantar ulcers result from a lack of plantar sensitivity. Objective: This study aimed to describe the treatment provided to patients with leprosy-induced plantar ulcers.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with plantar ulcers treated at Sarah Hospital in Brasilia from 2006 to 2016 and collected information about sex, age, etiology, location, and treatment.

Results: A total of 27 patients (17 [62.96%] men, 10 [37.04%] women; 40.74% were aged 41-60 years) were treated from Goiás and the Federal District. All required ≥1 surgical procedure.

Conclusion: A higher frequency of advanced grade was observed in men, primarily on the first toe. All needed surgical and non-surgical procedures and achieved complete wound healing. Transtibial amputation was required in 1 case and toe amputation in 7 cases; 90% patients developed ulcer recurrence after 1 year.

Keywords: Foot ulcer; Wounds and injuries; Leprosy; Treatment outcome; Therapeutics.

RESUMO

Introdução: A úlcera plantar por hanseníase é uma lesão no pé resultante da falta de sensibilidade plantar. O objetivo é descrever o tratamento realizado em portadores de úlceras plantares por hanseníase.

Métodos: Estudo de prontuários de portadores de úlcera plantar atendidos no Hospital Sarah em Brasília, de 2006 a 2016, quanto ao sexo, idade, etiologia, localização e tratamento.

Resultados: Foram atendidos 27 pacientes, 17(62,96%) homens e 10 (37,04%) mulheres, procedentes de Goiás e DF, na faixa etária de 41 a 60 anos (40,74%). Todos necessitaram de um ou mais procedimentos cirúrgicos.

Conclusão: Observou-se maior frequência no sexo masculino, grau avançado, localizadas no primeiro artelho. Todos necessitaram de procedimentos cirúrgicos e não cirúrgicos, evoluindo com cicatrização completa da ferida, amputação transtibial em um caso e de artelhos em sete casos, e 90% dos casos apresentaram recorrência da úlcera após um ano.

Palavras-chave: Úlcera do pé; Ferimentos e lesões; Hanseníase; Tratamento avançado; Terapêutica

INTRODUCTION

Leprosy-induced plantar ulcers are neurotrophic lesions located in the plantar region that result from repeated injuries due to a lack of sensitivity in the region. They affect various regions of the foot to different degrees of depth and severity and may lead to amputation of the toes or feet. Leprosy is a chronic granulomatous infection caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium leprae, is highly contagious, has low morbidity rates, and is endemic in Brazil. The transmission of leprosy occurs by intimate and prolonged contact of susceptible individuals with the bacilliferous patient through the inhalation of bacilli. Early diagnosis and treatment is best to prevent transmission1-4. According to Araújo, in 20035, the treatment for leprosy included specific chemotherapy, suppression of the reactional outbreaks, prevention of physical disabilities, and physical and psychosocial rehabilitation. This set of measures should be developed in health services from public or private health networks upon the notification of cases to the competent sanitary authority. Control actions are performed in progressive levels of complexity with local, regional, and national reference centers supporting the basic health network.

Leprosy is a chronic disease in which nerve injury causes sensory and motor changes that lead to deformities and the formation of skin ulcers. The disabling potential of leprosy is directly related to the penetration of gram-positive alcohol-acid-resistant bacilli into the peripheral nerves, especially Schwann cells, that damage the free nerve endings and induce changes in thermal, pain, and tactile sensitivity. When the protective sensitivity is compromised by the disease associated with the deformities of the foot resulting from the weakness of muscles, mechanical trauma, and use of inadequate footwear leads to hyperkeratosis, fissures, abrasions, blisters, erosions, and chronic ulcers1-5.

The main reason for foot ulcer formation in leprosy is the loss of protective sensitivity or total anesthesia in the region of the posterior tibial nerve, associated with paralysis of the intrinsic musculature, toe claw, loss of normal padding under the metatarsal head and volume of intrinsic muscles, anhidrosis, foot drop, and alteration in bone architecture, which cause exaggerated pressure under the metatarsal head and calcaneus to support and distribute the body weight6,7. Neural impairment within the tarsal tunnel can also cause secondary venous compression and even arterial compression, leading to foot stasis, which facilitates the production of plantar ulcers and delays in healing. The ulcers occur most often in the forefoot. Ulcers located in the lateral edge of the foot are infrequent and related with full foot drop or situations where there is paresis of the fibular muscles or varus foot position. Finally, the loss of volume of the intrinsic muscles of the hypothenar region of the foot allows the styloid process or the base of the fifth metatarsal to protrude, causing callus formation and ulceration of the fifth metatarsal. Ulceration of the calcaneus occurs less frequently but is more difficult to treat. Often it has a traumatic origin caused by nails, stones, or shoe irregularities; brisk walking or a very long stride can increase the forces in the calcaneus during the impact phase, increasing the friction forces6-8.

In a bibliographic survey of the Virtual Health Library database from 1978 to 2018 using the descriptors "leprosy" and "plantar lesions," we found 25 articles (12 specific to the topic); are few articles on the topic were identified in the international literature. Leprosy is one of 6 diseases that the World Health Organization considers a threat in developing countries and rare in Western countries. Nerve damage may occur before, during, and after disease treatment and can result in long-term disability and disfigurement as well as the stigma related to the disease9. The immune response and mechanisms involved in nerve injury are not clearly understood, and there is no predictive test to evaluate the extent of nerve damage or the best treatment of sequelae3.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to describe the treatment of a series of cases of leprosy-induced plantar ulcers in patients treated at a rehabilitation hospital.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional retrospective study of the medical records of patients with plantar ulcers treated at Sarah Hospital in Brasilia between January 2006 and January 2016. A non-probabilistic sample was obtained by convenience corresponding to the target population that attended a tertiary health care facility.

Data were collected regarding sex, origin, age, level of education, location, time of development, follow-up, and surgical and non-surgical procedures. Only cases of patients with plantar ulcers and a diagnosis of leprosy were included. The descriptive study of frequencies was performed using the Microsoft Excel program. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee/Social Security Agency (CAAE: 96147018.0.0000.0022), and the recorded data are part of the study group of plantar lesions treated in the Hospital Sarah Brasília.

RESULTS

In the study period, 27 patients with plantar ulcers were treated in the rehabilitation program at Sarah Hospital in Brasilia. Of them, 17 (62.96%; 10 [37.04%] men, 7 women; 40.74% were aged 41-60 years) were from Goiás, 14 (56%) were from the cities of Formosa, Cidade Ocidental, Planaltina, Cristalina, Pirenópolis, Iporá, Morrinhos, Pedregal, Santo Antônio do Descoberto, or Luziânia, and 8 (32%) were from the Federal District (FD); 21 (77.7%) had incomplete elementary education and worked in general and agricultural roles (Table 1). A detailed clinical examination of the foot was performed including a sensory test with an esthesiometer and a description of the specific plantar deformities including callus, ulcers, infectious signs, ankle and metatarsophalangeal mobility, distal sensory alterations in the 4 limbs, trophic alterations and the presence of clawing (Chart 1 and Figure 1). The anteroposterior and profile radiological examination of the feet was performed and when necessary, computed tomography and fistulography was requested. An electroneuromyography examination revealed predominantly axonal chronic diffuse sensorimotor peripheral polyneuropathy that was worse in the lower limbs; the most seriously affected region was the first toe in 41.94%, followed by multiple lesions (29%), the fifth toe in 16%, and the calcaneus in 12%. Follow-up was a mean 8 years, with complete healing of all cases but a 90% ulcer recurrence rate.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 17 | 62.96 |

| Female | 10 | 37.4 |

| Age range | ||

| <20 | 3 | 11.11 |

| 21-40 | 8 | 29.63 |

| 41-60 | 11 | 40.74 |

| >60 | 5 | 18.52 |

| Origin | ||

| GO | 14 | 55.56 |

| DF | 8 | 29.63 |

| PA | 2 | 7.41 |

| MA | 1 | 3.7 |

| RR | 1 | 3.7 |

| Level of education | ||

| Illiterate | 3 | 11.11 |

| Incomplete basic education | 21 | 77.78 |

| Secondary school | 2 | 7.41 |

| Higher education | 1 | 3.7 |

| Disease duration | ||

| <5 years | 8 | 29.63 |

| 6-20 years | 8 | 29.63 |

| >21 years | 11 | 40.74 |

| Profession | ||

| Student | 5 | 18.52 |

| Farm worker | 5 | 18.52 |

| General services | 8 | 29.63 |

| Domestic | 3 | 11.11 |

| Public servant | 1 | 3.7 |

| Not informed | 5 | 18.52 |

| Classification | ||

| Lepromatous | 20 | 74.1 |

| Dimorphous | 2 | 7.41 |

| Not identified | 5 | 18.52 |

| Ulcer location | ||

| First toe | 13 | 41.94 |

| Multiple regions | 9 | 29.3 |

| Fifth toe | 5 | 16.13 |

| Calcaneus | 4 | 12.9 |

| Plantar region changes due to leprous neuropathy | |

|---|---|

| Loss of protective sensitivity or anesthesia | Hyperkeratosis, fissures, scratches, blisters, erosions, and chronic ulcers |

| Claw deformity | Grade 1 - Toe tips touch the ground, allowing the formation of callus and ulceration |

| Grade 2 - Toes are hyperextended so the pads do not touch the ground | |

| Grade 3 - Metatarsophalangeal joints (MTP) are already fully displaced dorsally | |

| Intrinsic paralysis | Atrophy secondary to paralysis of the intrinsic muscles of the foot lead to loss of volume of soft parts, which normally assist in cushioning the soles of the feet; Alteration of plantar bone architecture |

| Impairment of autonomic fibers | Anhidrosis and loss of reflex circulatory adaptation |

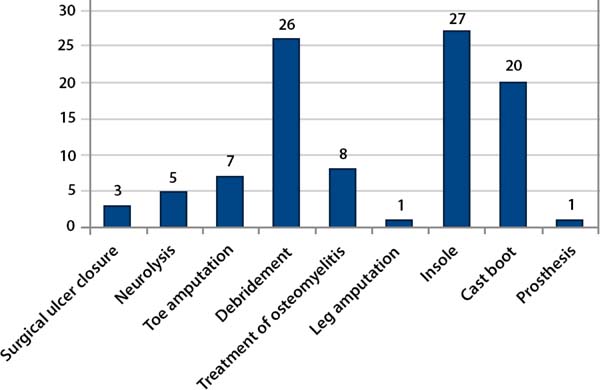

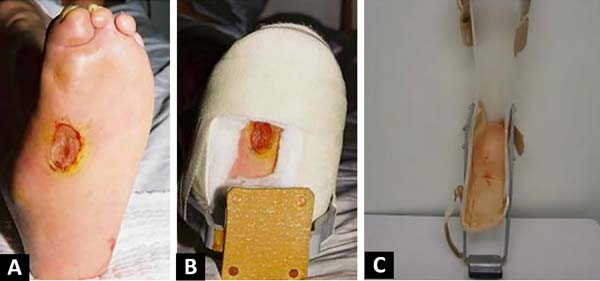

All patients completed a rehabilitation program that included guidelines on the disease, prevention of plantar lesions, a laboratory evaluation consisting of a motion sensitivity assessment with an esthesiometer, guidance on the use of dressings and locomotion help, orthoses and prostheses. All surgical procedures were required at some point in the evolutionary process. Among them, the ulcer was surgically closed in 3 (6%), with primary suture in all cases being required a relaxing longitudinal incision for central wound approach; there were 5 (10%) cases of tibial nerve neurolysis, 7 (14%) of toe amputation, 26 (52%) of debridement, 8 (16%) of osteomyelitis treatment (Figures 2 and 3); and 1 of transtibial amputation due to foot gangrene. Of the patients, 90% underwent more than 1 surgical treatment and 8 (16%) had bilateral ulcers.

The conservative treatment of plantar ulcers consisted of dressings with saline solution, non-alcoholic 1% iodine solution (Povidone), and oil rich in essential fatty acids (EFA); chemical debridement with proteolytic enzymes such as papain that are responsible for catalyzing the healing process and promoting tissue growth was used in cases with necrosis. In 3 cases of recurrent chronic ulcers under the head of the first metatarsal, metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis was performed.

Mechanical or surgical debridement was performed under anesthesia in a surgical center environment indicated in cases of infection, septic arthritis, or bone absorption. For these cases, the same lesion of the ulcer was used, with methylene blue being used as a marker to color the granulation tissue; the incision was increased when necessary to best approach the wound, and all necrotic tissue, bone, fascia, capsule, tendon sequestering, and other tissues with odor and characteristic aspect of necrosis and infection were removed. Sutures were placed to allow drainage or the placement of penrose drains, and the patient remained admitted and on antibiotic therapy according to culture and antibiogram without loading of the wound until the improvement occurred for a mean 60 days. In cases of toe amputation indicated by infection and osteomyelitis, a cutaneous flap of the disjointed digit was used to cover the ulcer.

Twenty-six patients underwent minor and partial debridement in the ambulatory environment, but each required >4 debridement procedures. For both hospitalized and outpatients, they were not cleared for plantar support until complete wound healing, on average after 3 months. The first dressing was done in the first postoperative period and whenever necessary, predicting the possibility of bleeding. In cases of chronic osteomyelitis with large areas located in the first radius and calcaneus, partial resection of the infected region was performed (Figure 4).

Among non-surgical procedures, all received a molded insole, 20 (41.67%) used a stirrup cast boot (Figure 3), and 1 received a lower limb prosthesis. After debridement or surgical treatment, the use of crutches, casts, or stirrup cast boots to aid in ambulation was recommended until the wound was completely healed. To make the plaster cast, the patient was placed prone or seated, the affected regions were protected from pressure, and the cast was changed weekly until the ulcer healed, which occurred around 3 months. The insole was molded and the patients were guided to use special footwear. In some adult cases, a stirrup orthosis was used, but poor patient acceptance due to discomfort and pain in other joints was noted (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

In Brazil, 25,200 cases of leprosy were recorded in 2016. However, compared with the rest of the world, the incidence is higher, 12.2 cases per 100,000, versus the international average of 2.9 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. From 2012 to 2016, 151,764 new cases were diagnosed; of them, 84,447 were men (55.6%). However, considering only severe (grade 2 or higher) physical disabilities, i.e., a visible deformity in the hands, feet, and/or eyes, the difference is marked, with an incidence of 15.17 cases for every 1 million men and 6.07 for every 1 million women 2,3,4,9,11.

This study involved a 10-year retrospective analysis. During the study period, 256 patients with plantar lesions were admitted to the locomotor rehabilitation hospital; of them, 27 (11%) had leprosy with grade 2 disability, which required multiple surgical and physical therapy procedures. Of these, 55.56% came from the state of Goiás, 77.78% had an incomplete elementary school education, and 29.63% were general service workers. The patients were followed by a multidisciplinary team of orthopedic surgeons, plastic surgeons, radiologists, nurses, physiotherapists, and orthopedic workshop support and plaster technicians.

The initial phenomenon of plantar lesions by leprous neuropathy was insensitivity to pain, which caused changes in plantar structure changes, plantar ulcers, and recurrent infections. Leprous neuropathy was due to bacillus invasion and the inflammatory process in the peripheral nerves classified as leprosy with grade 2 disability. The World Health Organization classifies physical disability in leprosy into the following 3 categories: Grade 0—without inability, without anesthesia and without visible deformity or damage to the eyes, hands or feet; Grade 1—anesthesia present, but no visible deformity or damage to the eyes, hands, or feet; and Grade 2—visible deformity or damage to eye (lagophthalmos, iridocyclitis, corneal opacities, severe visual impairment), hands (clawed hands, ulcers, finger absorption, thumb contracture and swollen hand), and feet (plantar ulcers, foot drop, inversion of the foot, toe scratches, toe absorption, collapsed foot and callosity)6. In agreement with this study, Moschioni, in 20106, described the lepromatous form with the greatest impact on physical disability and deformity, with a 16.5-fold greater chance of developing grade 2 versus other clinical forms6. In the lower limb, the posterior tibial and fibular nerves were the most commonly affected; when there is a lesion within these nerves, the patient presents a predisposition to plantar lesion formation, which begins with a superficial lesion and evolves to a deep ulcer, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis and gangrene6,7,9,11,12,13.

The algorithm proposed by Jeng and Wei in 199710 for the reconstruction of plantar traumas sequelae can help clinicians determine the best treatment option; however, it is worth noting that the main reasons for the development of plantar ulcers are related to the loss of protective sensitivity and structural changes due to muscle atrophy. Nevertheless, most wounds can heal by second intention with local care and rest, i.e., avoiding weight over the lesion and using appropriate shoes or insoles. In addition, these patients have changes in deep sensitivity and gait disorders, with claw-foot causing ligament injuries, claw deformities, and neuropathic arthropathies. The indication for the treatment of plantar lesions varies with the evolution, depth, diameter, and degree of infection. In early cases, the majority attended primary health services, health posts, and outpatient clinics, where it was possible to provide local dressings and care; in cases of infected or chronic wounds, debridement was required; in cases of absorption and greater severity, amputation of the toes was needed. One case of severe sensory, vascular, and bone involvement that presented plantar lesions at another stage on the contralateral limb required transtibial amputation.

According to published articles, resection of the metatarsal head is not recommended since this would lead to the accumulation of pressure on the next metatarsal head, i.e., simply transferring the problem to another region13-16. Other techniques have shown good results, such as the use of 2 bipediculated flaps in ulcer resection, i.e., removing the prominent bony parts that are infected and placing the bipediculated flap. Another option, the reverse sural flap, is associated with posterior tibial nerve decompression, which is believed to improve the sensitivity of the affected region; however, we consider this flap to be more complex, larger in volume, and with a higher risk of complications16,17. Other surgical and physiotherapeutic procedures9 have been used; however, in this study, the possibility of achieving wound healing with the following measures was verified: debridement, use of stirrup cast boot or orthosis, and avoiding plantar pressure and taking other preventive measures. However, the challenge lay in preventing recurrence. Corroborating published data13 demonstrated high rates of recurrence and relapse of plantar lesions as it occurs in 90% patients with a late diagnosis of a more advanced grade and lepromatous clinical form.

The results presented here corroborate the assertion that the recurrences and complications that lead to repeated and prolonged disorders in leprosy patients are due to more severe grade 2 lesions associated with the improper care of insensitive feet. Even in a service formed by a multidisciplinary team offering multiple interventions, when it was possible to complete wound closure, this group of patients still showed high rates of relapse and recurrence. The present study has limitations regarding the epidemiological analysis of leprosy in Brasilia, where treatment is provided in accordance with the guidelines and operational technical manual for surveillance, attention, and elimination of leprosy as a public health problem published by the Ministry of Health18. Moreover, the use of a non-probabilistic sample obtained by convenience corresponding to the target population attended in a tertiary health care facility described cases of patients with injuries and physical disabilities that required complex techniques and were referred to rehabilitation services. Other comparative studies of the prevalence and evolution of plantar lesions with a similar grading of incapacity and other grades are required.

We reinforce the need to prevent, diagnose, and treat the disease as the main targets for leprosy. Major endemic diseases challenge public health since they primarily affect disadvantaged people, i.e., those in poor living conditions and who lack basic sanitation, factors that contribute to their onset5,7,9,10,11,13.

CONCLUSIONS

The admitted patients with leprosy-associated plantar lesions treated in the rehabilitation service were more frequently older than 40 years, were male, and had a more advanced degree of disease affecting mainly the first toe and >1 plantar region. All patients required surgical and non-surgical procedures and achieved complete wound healing. However, there was 1 case of transtibial amputation and 7 cases of toe amputation, and 90% of our cases developed ulcer recurrence after 1 year.

COLLABORATIONS

|

KTB |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Final manuscript approval, Investigation |

|

GBM |

Data Curation, Project Administration, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

UPyS |

Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

AFSSAR |

Conception and design study, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

AGR |

Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

CZC |

Conceptualization, Investigation |

|

CFPAS |

Writing - Review & Editing |

REFERENCES

1. Guerrero MI, Muvdi S, León CI. Retraso en el diagnóstico de lepra como factor pronóstico de discapacidad en una cohorte de pacientes en Colombia, 2000-2010. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;33(2):137-43.

2. Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS). Estratégia global aprimorada para redução adicional da carga da hanseníase (Período do plano: 2011-2015) [Internet]. Brasília (DF): Organização Pan-Americana de Saúde; 2010; [cited 2014 dec 31]. Disponível em: http://www.paho.org/bra/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=1044&Itemid=423

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Global leprosy update, 2013; reducing disease burden. Wkly Epidemiol Rec [Internet]. 2014 Sep; [cited 2014 dec 31]; 89(36):389-400. Disponível em: http://www.who.int/wer/2014/wer8936.pdf

4. Portaria nº 3.125, de 07 de outubro de 2010 (BR). Aprova as Diretrizes para Vigilância, Atenção e Controle da Hanseníase. Diário Oficial da União [Internet], Brasília (DF). 15 out 2010; [cited 2014 dec 31]. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2010/prt3125_07 _10_2010.html

5. Araújo MG. Hanseníase no Brasil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop [Internet]. 2003 May/Jun; [cited 2014 oct 23]; 36(3):373-82. Disponível em:http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rsbmt/v36n3/16339.pdf

6. Moschioni C, Antunes CMF, Grossi MAF, Lambertucci JR. Risk factors for physical disability at diagnosis of 19,283 new cases of leprosy. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop [Internet]. 2010 Feb; [cited 2014 dec 31]; 43(1):19-22.Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822010000100005

7. Monteiro LD, Alencar CHM, Barbosa JC, Braga KP, Castro MD, Heukelbach J. Incapacidades físicas em pessoas acometidas pela hanseníase no período pós-alta da poliquimioterapia em um município no Norte do Brasil. Cad Saude Publica [Internet]. 2013; [cited 2014 dec 31]; 29(5):909-20. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102311X2013000500009

8. Paschoal JAA, Paschoal VDA, Nardi SMT, Rosa PS, Ismael MGS, Sichieri EP. Identification of urban leprosy clusters. Scientific World J [Internet]. 2013; [cited 2014 dec 31]; 219143:[aprox.6 telas]. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/219143

9. Alves ED, Ferreira TL, Ferreira IN. Hanseníase: avanços e desafios. Brasília (DF): NESPROM; 2014.

10. Jeng SF, Wei FC. Classification and reconstructive options in foot plantar skin avulsion injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 May;99(6):1695-703;discussion:1704-5.

11. Gonçalves A. Realities of leprosy control: updating scenarios. Rev Bras Epidemiol [Internet]. 2013 Sep; [cited 2014 dec 31]; 16(3):611-21. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1415-790X2013000300006

12. Solomon S, Kurian N, Ramadas P, Rao PS. Incidence of nerve damage in leprosy patients treated with MDT. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1998 Dec;66(4):451-6.

13. Foss NT, Souza CS, Goulart IMB, Gonçalves HS, Virmond M. Hanseníase: episódios reacionais. In: Associação Médica Brasileira, Conselho Federal de Medicina. Projeto diretrizes. São Paulo: AMB; 2003. p.161-179.

14. Lima LS, Jadão FRS, Fonseca RNM, Silva Junior GF, Barros Neto RC. Caracterização clínica-epidemiológica dos pacientes diagnosticados com hanseníase no município de Caxias, MA. Rev Bras Clin Med [Internet]. 2009; [cited 2014 dez 31]; 7:74-83. Disponível em: http://files.bvs.br/upload/S/1679-1010/2009/v7n2/a001.pdf

15. Moreira FL, Nascimento AC, Martins ELB, Moreira HL, Lyon AC, Lyon S, et al. Hanseníase em Alfenas: aspectos epidemiológicos e clínicos na região sul do estado de Minas Gerais. Cad Saude Colet [Internet]. 2009; [cited 2014 dez 31]; 17(1):131-41. Disponível em: http://www.cadernos.iesc.ufrj.br/cadernos/images/csc/2009_1/artigos/Art_9CSC09_1.pdf

16. Amaral EP, Lana FCF. Análise espacial da Hanseníase na microrregião de Almenara, MG, Brasil. Rev Bras Enferm [Internet]. 2008 Nov; [cited 2014 dez 31]; 61(spe):701-7. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672008000700008

17. Ismail HE, El Fahar MH. Sural artery perforator flap with posterior tibial neurovascular decompression for recurrent foot ulcer in leprosy patients. GMS Interdiscip Plast Reconstr Surg DGPW. 2017 Jan;31:6:Doc01.

18. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Guia de vigilância em saúde: volume único. 3ª ed. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2019; [cited 2014 ago 5]. Disponível em: http://www.saude.pr.gov.br/arquivos/File/DiretrizesdoManuaTcnicoOperacionaldeHansenia se.pdf

1. Hospital Sarah Brasília da Rede Sarah de Hospitais de Reabilitação, Brasília, DF,

Brazil.

2. Centro Universitário do Planalto Central Aparecido dos Santos, Brasília, DF, Brazil.

3. Secretaria de Estado de Saúde Fundação de Ensino e Pesquisa em Ciências da Saúde,

Brasília, DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Katia Torres Batista SMHS 501, Bloco A, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Zip code: 70335-901. E-mail: katiatb@terra.com.br

Article received: April 30, 2019.

Article accepted: October 21, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter