Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Reconstruction of abdominal wall and vulvar defects after endometriosis resection

Reconstrução de defeito de parede abdominal e vulva após ressecção de endometriomas extracavitários

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Endometriosis is characterized by the presence

of functional endometrial tissue (endometrial glands and

stroma) outside the uterine cavity. However, only a few cases of

extrapelvic endometriosis have been described in the literature.

Methods: This study reports the case of a patient from the

author's plastic surgery service who underwent surgery in

September 2013 at a hospital in Brasília, Federal District,

Brazil. The study was conducted according to the principles

of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the patient signed an

informed consent form.

Results: A 30-year-old female patient

presented with dysmenorrhea, pain, and paresthesia in the

right inguinal region as well as a firm nodule in the labia majora

with scars from two surgical resections of endometriosis.

The gynecology team performed endoscopic resection of the

uterine cavity lesions, inguinal canal content, nodules in the

right labia majora, umbilical scar, and part of the aponeurosis.

The abdominal wall and vulvar defects caused by the resection

were repaired using a laterally based random lower abdominal

flap as one of the vertices of a Z-plasty.

Conclusion: The flap

described in this study is an alternative and satisfactory method

for repairing large defects in the inguinal and vulvar regions.

Keywords: Reconstruction; Vulva; Abdomen; Plastic surgery; Endometriosis.

RESUMO

Introdução: Endometriose é a presença de tecido endometrial funcionante (glândulas endometriais e estroma) em localização fora da cavidade endometrial. Implantes endometrióticos extrapélvicos têm sido ocasionalmente descritos na literatura.

Métodos: Este é um relato de caso de uma paciente do serviço de cirurgia plástica do autor, operada em setembro de 2013 em um hospital de Brasília-DF. O trabalho seguiu os princípios de Helsinque e o termo de consentimento livre e esclarecido foi realizado.

Resultados: O trabalho se trata de uma paciente de 30 anos que apresentava dismenorreia, dor e parestesia em região inguinal direita, nódulo endurecido em grande lábio direito com cicatrizes de duas ressecções de focos de endometriose. A equipe de ginecologia realizou ressecção endoscópica das lesões cavitárias, do conteúdo do canal inguinal, do nódulo no grande lábio direito, da cicatriz umbilical e parte da aponeurose. Após se instalarem os defeitos de parede abdominal e vulva, a cirurgia plástica realizou a reconstrução com retalho de abdome inferior randômico, baseado lateralmente, como um dos vértices de uma zetaplastia.

Conclusão: O retalho descrito no trabalho é uma alternativa na reconstrução da região inguinal e vulva, em casos de grandes defeitos, obtendo um resultado satisfatório.

Palavras-chave: Reconstrução; Vulva; Abdome; Cirurgia plástica; Endometriose

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of functional endometrial tissue (endometrial glands and stroma) outside the uterine cavity and uterine musculature; this tissue usually responds to hormonal stimulation1,2,3,4. The uterine cavity is the site most commonly affected by endometriosis. Nonetheless, few cases of extrapelvic endometriotic implants have been described in the literature5,6.

The diagnosis of endometriosis should be considered in women with a clinical history of dysmenorrhea, chronic acyclic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, cyclic intestinal and urinary symptoms, and infertility7. Confirmation of this disease is only possible by histopathological analysis of the tissue fragments obtained by invasive procedures because no adequate clinical marker is currently available1.

Endometriosis can occur in many different locations, including the vagina, vulva, cervix, perineum, inguinal canal, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, pulmonary tract, lungs, limbs, and skin. It can be considered as a nonspecific tissue in the groin by plastic surgeons or as an inguinal hernia by general surgeons2.

After lesion removal, the plastic surgeon’s challenge is repairing the open area, restoring function, and achieving the best aesthetic results. Several strategies can be used to close the lesion depending on lesion location and size and patient status8.

OBJECTIVE

This study describes a viable option for repairing the inguinal region and labia majora using a lower abdominal flap as one of the vertices of a Z-plasty with good aesthetic results.

METHODS

The analyzed data were collected from medical records, patient interviews, photographic records, and a literature review. This patient was treated in Brasília, Federal District, Brazil, between September 2013 and February 2016. Patient privacy was protected, and the patient authorized the publication of the data and signed an informed consent form. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

J.A.K, a 30-year-old nulliparous female patient with a body mass index of 29 kg/m2 and gynecological follow-up, presented with a 3-year history of dysmenorrhea, pain, and paresthesia in the right inguinal region, functional limitation during the menstrual period, and a firm nodule in the labia majora with scars from two surgical endometriosis resections. Bleeding occurred monthly through the umbilicus. The gynecology team presented surgical planning involving the endoscopic resection of cavitary lesions, inguinal canal content, nodules in the right labia majora with margins, umbilicus, and part of the aponeurosis. Nonetheless, larger defects requiring surgical reconstruction developed after the excision of lesions in the inguinal region, right labia majora, and umbilicus.

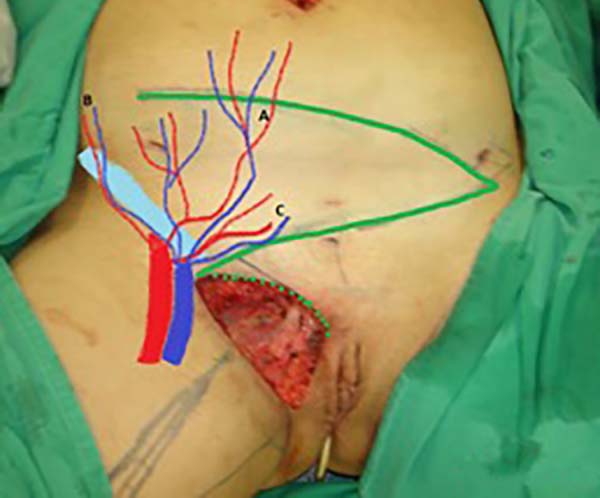

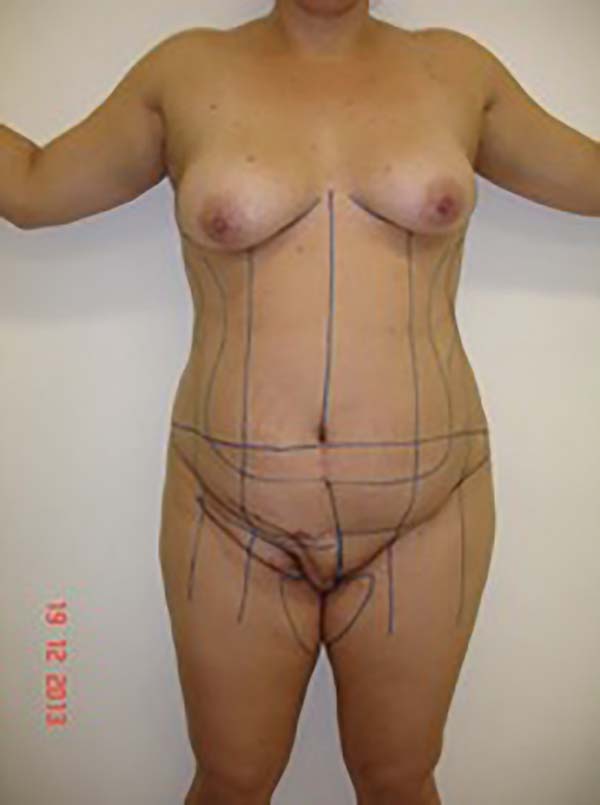

Surgical planning included repair of the abdominal wall in the periumbilical region, plication of the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis muscles 5 cm above and 5 cm below the umbilical scar, closure of the abdominal wall defect, construction of a new umbilicus, and suturing between the dermis and the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis (the umbilicus was resected en bloc) (Figure 1). In the inguinal region, the integumentary defect affected more than 70% of the right labia majora and the thigh root region with exposure of the inguinal canal and communication of the uterine cavity with the external environment because the endometriosis impacted the region from the uterine cavity to the labia majora (apparently along the funiculus spermaticus) (Figure 2). The surgical planning was based on recurrence potential, minimizing donor area damage to prevent an inguinal hernia due to the defect, and the use of local flaps to increase vascularization (Figure 3).

In the first surgical procedure, larger detachments were not made in the umbilical region to prevent the development of endometriotic implants in other sites; only restoration of the abdominal wall with plication of the rectus abdominus muscle and neo-omphaloplasty were performed (Figures 4 and 5). In the inguinal region, the defect (approximately 10 cm × 15 cm) was reconstructed using a laterally based random lower abdominal flap as one of the vertices of a Z-plasty (Figure 6).

To repair the inguinal canal, Prolene® mesh was attached to the remaining aponeuroses and the pectineal line of the ischium (Figure 7). Among the possible choices (fasciocutaneous flap of the thigh muscles and adjacent muscles), we opted for the fasciocutaneous flap of the right iliac fossa, which did not require further detachment (its design was similar to that of Z-plasty).

The surgical team discussed with the patient the possibility of a second approach involving abdominoplasty at the height of the lesion excision scar, liposculpture with liposuction of the flap, and symmetrization with fat grafting (Figures 8 and 9).

After 3 months, the patient’s status had a good evolution without significant complications, and she underwent a second surgical procedure involving liposculpture abdominoplasty and flap thinning, i.e., liposuction of the right labia majora and inguinal region and fat grafting in the left labia majora for symmetrization (Figure 10).

Two years and one month after the second surgical procedure, the patient underwent a mastopexy with breast augmentation, at which time new procedures (liposuction and fat grafting) were performed that produced good results (Figures 11 and 12). The endometriosis did not recur, and no significant complications resulted from the three surgical procedures.

DISCUSSION

Most cases of perineal, vulvar, and abdominal wall endometriosis occur at or near surgical scars, probably due to mechanical transplantation of endometrial tissue during episiotomy, vulvar surgery, or accidental trauma9. In contrast, invasion of the lymphovascular space is considered the best explanation for the pathogenesis of the spontaneous development of perineal lesions9.

Endometriosis is a chronic estrogen-dependent condition that affects 6-10% of women of reproductive age. Ectopic endometrial tissue can appear anywhere in the body, whereas endometriotic implants tend to occur in the pelvic region10. Yela et al. (2017)11 observed that endometriotic lesions were located predominantly in previous cesarean section scars. In contrast, the incidence of abdominal wall endometriosis is low.

The abdominal wall is impaired in 0.03-3.50% of cases of endometriosis, and some studies reported rates of up to 12%10,11. However, endometriosis has been observed in surgical incisions after conventional and laparoscopic hysterectomy, appendectomy, and inguinal hernia repair. In these cases, lesions that were frequently evaluated by a general surgeon for diagnostic confirmation were misdiagnosed as hernia, hematoma, granuloma, abscess, or lipoma11. Moreover, extrapelvic endometriosis is relatively rare10.

The four diagnostic signs of extrapelvic endometriosis are the intermittent enlargement of endometriotic lesions, increased sensitivity of lesions near the menstrual period, dyspareunia, and bleeding9.

Pedunculated skin flaps, including local and regional flaps, are commonly used for vulvar reconstruction12. Defects (<20 cm2) of the upper third of the vulva can be closed with local flaps such as rhomboid and V-Y flaps. Partial-thickness skin grafts are an option in patients who do not require or had no previous radiotherapy. More elaborate flaps may be necessary for larger defects8,13,14.

Defects of the middle third of the labia majora can be repaired using pudendal-thigh (Singapore), gracilis myocutaneous, and gluteal myocutaneous flaps8,13.

In the lower third of the vagina or in the vaginal/perianal orifice, defects are best repaired using gluteal fold flaps, which were initially described by Yii and Niranjan in 0000x and modified by Hashimoto et al. (1999)8.

Perineal reconstruction is a significant surgical challenge because of the need to restore urogenital and anorectal functions. This type of procedure impacts multiple tissues and systems that may become contaminated with bacteria present in flaps and grafts, increasing the risk of infections and wound dehiscence. The perineum is also subject to significant pressure from the reclining and sitting positions, potentially exposing the surgical wound to ischemic pressure and necrosis8,13.

Deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps are commonly used and contain a thick subcutaneous fat layer12.

Several flaps are available for reconstructing the inguinal region, including those derived from the sartorius, rectus abdominis, tensor fascia lata, vastus lateralis, lateral and anterior thigh, and gracilis muscles15.

Sbitany et al. (2010)15 recommended rectus femoris myocutaneous flaps for repairing defects in the inguinal region. The advantages of these flaps include an arc of rotation sufficient to cover the entire region and the presence of a reliable vascular pedicle.

In our study, the lower abdominal flap was prepared and achieved good functional and aesthetic results. Vulvar reconstruction is usually limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissues and involves restoring the genitalia and producing good aesthetic and functional results8.

The donor area endured minimal damage that was repaired by abdominoplasty, which provided a good flap for repairing the defect in the inguinal region and the right labia majora. During the surgical procedure, polypropylene mesh was placed in the inguinal region to prevent possible herniation in this region and fat grafting to improve the aesthetic results.

Many flaps are available for correcting defects in the labia majora and inguinal region, including V-Y and rhomboid flaps using gracilis, buttock, and thigh muscles. This study reported an alternative approach for reconstructing a body region for which surgical repair is a challenge based on the patient’s technical and physiological difficulties and involved the use of a random fasciocutaneous flap to which the blood vessels of the lateral abdominal wall provided the vascular supply.

CONCLUSION

The use of a laterally based random lower abdominal flap as one of the vertices of a Z-plasty is an alternative for reconstructing the inguinal and vulvar regions in cases of large defects. This technique achieves satisfactory aesthetic results in these regions without impairing shape or volume while preserving the natural groove in the thigh root. Furthermore, the thickness of the dermal fat allows functional remodeling with liposuction and fat grafting.

COLLABORATIONS

|

JDLGA |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing - Original Draft Preparation |

|

JGOJ |

Data Curation, Review & Editing |

|

RSCC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

ACC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation |

|

RCSD |

Analysis and/or data interpretation |

|

AAD |

Analysis and/or data interpretation |

|

JCD |

Analysis and/or data interpretation |

REFERENCES

1. Acetta I, Acetta P, Acetta AF, et al. Endometrioma de parede abdominal. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2011 Mar;24(1):26-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-67202011000100006

2. Cervini P, Wu L, Shenker R, et al. Endometriosis in the canal of Nuck: Atypical manifestations in an unusual location. Can J Plast Surg. 2004;12(2):73-75. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/229255030401200202

3. Pontrelli G, Cozzolino M, Stepniewska A, et al. Primary vaginal adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth arising in recurrent endometriosis: feasibility of laparoscopic treatment and review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016 Jul/Aug;23(5):833-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2016.03.019

4. Eyvazzadeh AD, Smith YR, Lieberman R, et al. A rare case of vulvar endometriosis in an adolescent girl. Fertil Steril. 2009 Mar;91(3):929.e9-11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.026

5. Kondo W, Ribeiro R, Trippia C, Zomer MT. Endometriose profunda infiltrativa: distribuição anatômica e tratamento cirúrgico. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2012 Jun;34(6):278-84. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-72032012000900006

6. Odobasic A, Pasic A, Iljazovic-Latifagic E, et al. Perineal endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Tech Coloproctol. 2010;14(Suppl 1):S25-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0642-8

7. Peloggia A, Petta C. Endometriose profunda: como abordar?. Femina. 2011 Set;39(9):451-457.

8. Weichman KE, Matros E, Disa JJ. Reconstruction of peripelvic oncologic defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Oct;140(4):601e-612e. PMID: 28953736 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003703

9. Nasu K, Okamoto M, Nishida M, Narahara H. Endometriosis of the perineum. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013 May;39(5):1095-7. PMID: 23496239 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.12003

10. Okoshi K, Mizumoto M, Kinoshita K. Endometriosis-associated hydrocele of the canal of Nuck with immunohistochemical confirmation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:354. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1522-x

11. Yela DA, Trigo L, Bennetti-Pinto CL. Evaluation of cases of abdominal wall endometriosis at Universidade Estadual de Campinas in a period of 10 years. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017 Aug;39(8):403-407. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1603965

12. Zeng A, Qiao Q, Zhao R, Song K, Long X. Anterolateral thigh flap-based reconstruction for oncologic vulvar defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 May;127(5):1939-45. PMID: 21532422 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31820e9223

13. Hollenbeck ST, Toranto JD, Taylor BJ, et al. Perineal and lower extremity reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Nov;128(5):551e-563e. PMID: 22030517 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b6b87

14. Lee PK, Choi MS, Ahn ST, et al. Gluteal fold V-Y advancement flap for vulvar and vaginal reconstruction: a new flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Aug;118(2):401-6. PMID: 16874210 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000227683.47836.28

15. Sbitany H, Koltz PF, Girotto JA, Veja SJ, Langstein HN. Assessment of donor-site morbidity following rectus femoris harvest for infrainguinal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010 Sep;126(3):933-40. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e604a1

1. Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Brasília, DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Jefferson Di Lamartine Galdino Amaral SCN Quadra 2 Ed. Liberty Mall Torre A, Salas 1121 e 1123, Asa Norte, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Zip Code: 70297-400. E-mail: jefferson@dilamartine.com.br

Article received: February 10, 2019.

Article accepted: June 10, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter