Special Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Redefining natural abdominal anatomy in abdominoplasty using conventional liposuction: A prospective study

Redefinição natural do abdome em abdominoplastia com uso de lipoaspiração convencional: estudo prospectivo

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Abdominoplasty techniques have constantly

evolved since 1899. With modern liposuction techniques, the

concept of high-definition liposuction aims to correct stigmas

secondary to the procedure, such as a "tense" appearance and

lack of natural abdominal convexity and concavity.

Methods: Here we propose a technique to redefine the natural abdominal

anatomy using traditional lipoabdominoplasty with selective

liposuction to achieve more natural-looking surgical results

that are reproducible for most patients. This study included

21 abdominoplasty procedures using the described technique

performed between November 2018 and May 2019. The

technique showed satisfactory ability to achieve a natural

abdominal appearance using deep and superficial liposuction

in abdominal shadow areas.

Conclusion: The study showed

that the technique is safe from a vascular point of view and

reproducible due to the use of conventional liposuction,

which is available to the vast majority of plastic surgeons.

Keywords: Surgery, Plastic; Abdomen; Abdominoplasty; Lipectomy; Rectus abdominis.

RESUMO

Introdução: A evolução da abdominoplastia se mantém constante desde 1899. Atualmente, com o avanço das técnicas de lipoaspiração, o conceito de lipoaspiração de alta definição tem como objetivo de corrigir estigmas causados pelo procedimento, como o aspecto "tenso" e a falta de convexidades e concavidades naturais abdominais.

Métodos: Apresentamos uma proposta de busca da redefinição natural do abdome, através da lipoabdominoplastia tradicional com lipoaspiração seletiva, procurando obter resultados cirúrgicos com padrão natural, reproduzível para a maioria dos pacientes. Foram realizadas 21 abdominoplastias, entre novembro de 2018 e maio de 2019, utilizando a técnica descrita.

Resultados: A técnica demonstrada apresentou resultados estéticos satisfatórios em obter a aparência abdominal natural através da lipoaspiração profunda e superficial, em áreas de sombras abdominais.

Conclusão: O trabalho demonstrou-se seguro sob o ponto de vista vascular, além de ser reprodutível ao passo que utiliza lipoaspiração convencional, utilizada pela ampla maioria dos cirurgiões plásticos.

Palavras-chave: Cirurgia plástica; Abdome; Abdominoplastia; Lipectomia; Reto do abdome

INTRODUCTION

Abdominoplasty techniques have constantly evolved since 1899, when Kelly1 performed an elliptical lipectomy to correct abdominal lipodystrophy. A century later, incisions are lower and the standard largely detached abdominal flap provides greater mobility and greater skin excision and umbilical transposition. In 2001, Saldanha et al.2 broke paradigms by presenting a new surgical concept for the aesthetic treatment of the abdominal region following the principles of liposuction to preserve lateral perforating vessels and allowing small detachment of the supraumbilical region with superior aesthetic results2. From 2003 to 2009, this technique was improved and became the modern treatment of abdominal lipodystrophy3,4,5. Modern liposuction techniques are currently used; in 20186, Hoyos et al. introduced the concept of high-definition liposuction in abdominoplasty using ultrasound-assisted liposuction and neoumbilicoplasty to correct stigmas secondary to the procedure, such as a “tense” appearance and a lack of natural abdominal convexity and concavity6. Here we propose a technique to redefine natural abdominal anatomy using traditional lipoabdominoplasty with selective liposuction to achieve more natural-looking surgical results that are reproducible for most patients.

OBJECTIVE

To describe a technique of superficial and deep abdominal liposuction on the linea alba and semilunar line to better define the abdominal flap in abdominoplasty.

METHODS

This study included abdominoplasty patients presenting with type IV and V lipodystrophy as classified by Pitanguy in 19955. The patients were non-smokers who maintained a stable weight in the previous 6 months, had a body mass index below 30, and had no prohibitive comorbidities for the procedure. All procedures were approved by the medical board of the Santa Casa Plastic Surgery and Reconstructive Microsurgery Service, and all patients signed an informed consent form. Between November 2018 and May 2019, 21 procedures were performed using the described technique. The same surgeon performed each procedure, followed up each patient with photographic records at 30, 90, and 180 days postoperatively, and continues following them today.

Marking

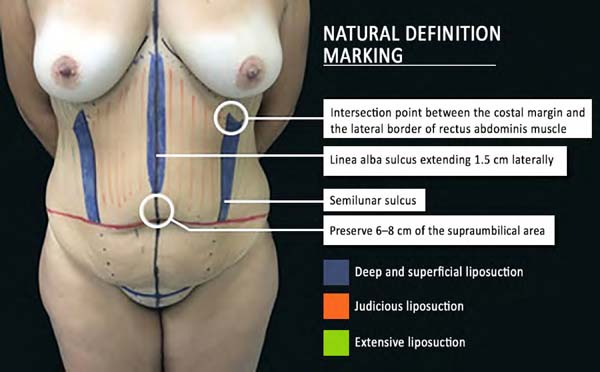

After marking the dermolipectomy area with the patient in the orthostatic position, we identify the intersection between the costal margin and the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle (point A) and draw a line through the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle from this point to the pubic symphysis according to the patient’s anatomy. This line is measured bilaterally up to the linea alba to avoid asymmetry.

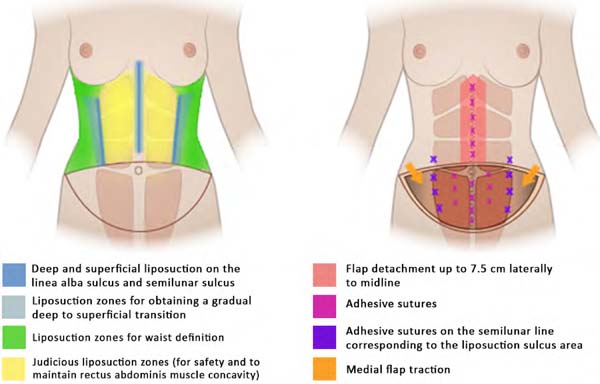

To delimit the liposuction area (deep and superficial) and achieve higher definition, the costal line is marked bilaterally up to 4-5 cm from point A to form point B. Next, a line is drawn from point B to the rectus abdominis muscle insertion, forming the future semilunar sulcus, the area where the deep and superficial liposuction will be performed. The midline where the liposuction will be performed is marked up to a point about 5-6 cm from the navel to prevent an infraumbilical midline depression and to preserve distal vascularization. The most distal part of the abdominal flap and a lateral area of 1.5 cm are demarcated as a transition zone between the linea alba and the rectus abdominis muscle (Figure 1).

Surgery

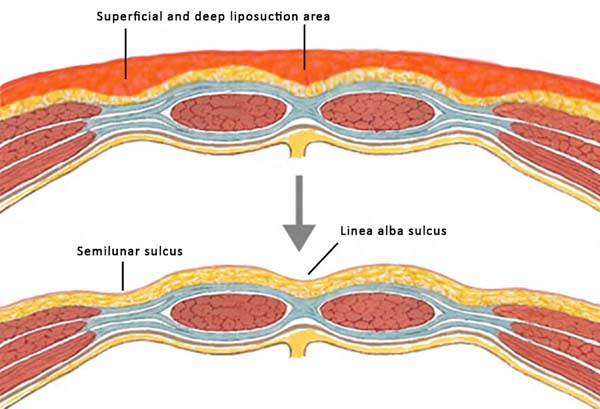

The patient undergoes general anesthesia with preventive measures taken to avoid deep vein thrombosis, such as knee flexion, the use of pneumatic compression boots, and the use of a thermal blanket for temperature control. If planned, surgery begins with the patient in the prone position for liposuction of the back. Surgical drapes are changed and the patient is moved to a supine position. After antisepsis and the placement of sterile drapes, the abdominal flap area is infiltrated with a tumescent solution of 0.9% saline and adrenaline 1:1,000,000. The patient is placed in a supine position with a slight extension of 15° and the liposuction begins in the supraumbilical linea alba through an incision in the internal cranial part of the navel using a 3-mm cannula in the superficial plane and 4-mm cannula in the deep plane with care taken not to mark an area up to 7 cm from the navel since it is the infraumbilical area where the linea alba is not visible. Next, liposuction is performed in a transition area of approximately 2 cm laterally to the linea alba to create a gradual transition with the rectus abdominis muscle. The entire rectus abdominis area is deeply aspirated to thin the flap without pairing with the central area. After liposuction is performed in the central area, the concave region determined by the semilunar line is recreated to obtain the semilunar sulcus with deep and superficial liposuction performed through the inguinal incisions at the level of the rectus abdominis muscle insertion. We used a 4-mm cannula for the deep liposuction and a 3-mm cannula for the superficial liposuction. It is important to aspirate up to 3-4 cm above the demarcated area, correcting the descending distance of the flap.

After satisfactory fat aspiration from this area and a natural shadow effect are achieved, the flanks are deeply aspirated to obtain a better body outline.

After the liposuction is completed, an abdominoplasty is performed. The flap is gradually brought down using adhesive sutures as described by Baroudi and Ferreira in 19987, maintaining the position of the semilunar sulcus and linea alba recreated in the flap according to the patient’s abdominal wall anatomy using sutures at the corresponding points. If necessary, the procedure is followed by an open lipectomy as described by Saltz in 20148. No drains are used (Figure 2). The patient is kept in Fowler’s position in the recovery room and discharged the next day. An outpatient return is scheduled 3 days after surgery for a follow-up consultation. The mean surgical time is 240 minutes when there is associated back liposuction and 200 minutes when no back liposuction is performed. The patient starts lymphatic drainage 5 days postoperatively.

RESULTS

The cases operated during this period presented no complications. Surgical results are shown in Figures 3-7. There was a greater prominence of abdominal concavities such as the semilunar sulcus and linea alba.

DISCUSSION

Although the results of the current lipoabdominoplasty techniques are reproducible and aesthetically satisfactory, stigmas such as the stretched aspect of the abdominal flap are relevant since they result in an unnatural appearance6. In 20049, Lockwood described unwanted results like a tense appearance in the central abdominal region, excess skin, inguinal and lateral sagging, a suprapubic depressed scar, cranially oriented pubic hair, poor waist definition, and hypertrophic and asymmetric scars. In 20186, Hoyos et al. added a tense-looking abdomen, lack of convexity and concavity, short distance between the navel and scar, constricted or larger than normal navel, hyperchromic umbilical scar, and residual umbilical hernia to the list.

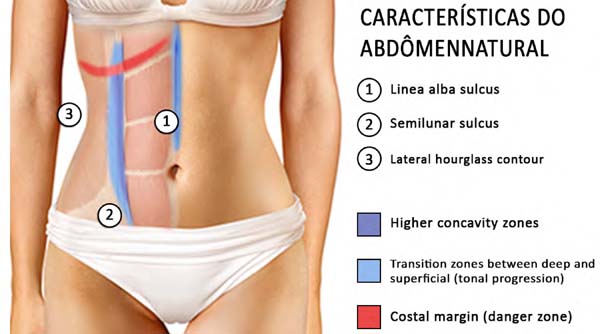

Abdominal contour depends on age, genetics, muscle mass, intra- and extra-abdominal adiposity, pregnancy history, pathologies, and body posture. The shape of the abdominal wall is created by the relationship between the musculoskeletal system, subcutaneous tissue, fibroadipose tissue, and skin. These relationships give the appearance of an aesthetic contour with light reflecting prominences and shadowing depressions. A shadow is formed on the midline by the depression of a sulcus corresponding to the linea alba from the xiphoid to the navel. Laterally to this sulcus, there are two broad vertical convex areas produced by the prominence of the rectus abdominis muscles that join together beneath the navel. More laterally and slightly posteriorly to these prominences, there are two broad depressions called the semilunar sulci that produce a “lyre” shape by insertion of the skin into the condensation of the oblique muscles fasciae, the external border of the rectus muscles, the inguinal ligaments, and the pubis10.

Therefore, a natural-looking abdomen has a marked and subtle linea alba above the navel and a transition region between the lateral border of the rectus abdominis and oblique muscles with well-defined concavity, which in lateral view has a double “S” shape. This is the natural appearance that patients want. Since the morphological profile of most patients is not athletic (Figure 8), the objective of this study is not to achieve a high-definition liposuction standard with well-defined abdominal muscles (Figure 8).

To produce three-dimensional effects, we must understand the concept of “chiaroscuro,” a painting technique introduced by Leonardo Da Vinci in the 1511 century. Chiaroscuro, also called tonal perspective, is defined by the contrast between light and shadow in the representation of an object, creating a three-dimensional effect by predicting and reproducing the effect of light on the object. Tonal progression creates depth perception and a sensation of plenitude where shadows intensify as they move away from light. In liposuction, we create shadows by selectively removing fat from an area, visually transforming it into a concave area, and consequently making the adjacent area more convex. Therefore, we create shadows by removing more subcutaneous fat in a given area and add light by forming convexities. The transition area between these two points determines how natural the final result will look. It is important to highlight that a sudden change between light and dark will create an artificial appearance.

After this study, we determined three points of consideration to achieve this natural appearance: correct preoperative anatomical marking, proper shadow-convexity transition effect during liposuction, and flap repositioning on the abdominal wall (Figures 9 and 10).

Safe liposuction on the abdominal flap has currently been reviewed. In 197912, Huger divided the abdominal vascular supply into three zones: zone I, the central abdomen, supplied by the deep and superficial branches of the superior epigastric artery; zone III, the peripheral abdomen, supplied by intercostal, subcostal, and lumbar perforators; and zone II, the inferior abdomen, supplied by the deep inferior epigastric artery, deep and superficial circumflex iliac artery, and superficial external pudendal artery. During abdominoplasty, zone II is resected; there is concern regarding flap viability after detaching zone I. In articles written in 1995 and 2000, Matarasso13,14recommended being careful when aspirating the central abdomen and advised the use of a thick flap. More recently, with safer and more limited detachments, some studies suggest that liposuction in the central abdomen is safe as long as the lateral perforating vessels are preserved15,16 and the procedure does not exceed 7.5 cm laterally of midline17.

Recent studies on flap vascularization compared the preservation and total sectioning of perforating vessels using indocyanine green fluorescence imaging, showing no differences in perfusion and corroborating the thesis that even larger dissections can be performed with liposuction18. The technique presented in this study does not include aggressive liposuction on the central abdomen to maintain some level of rectus abdominis muscle convexity and, theoretically, increasing safety during the procedure. Deep and superficial liposuction is performed only in selected areas according to the patient’s anatomy.

CONCLUSION

The technique showed satisfactory aesthetic results of achieving a natural abdominal appearance using deep and superficial liposuction in abdominal shadowed areas. This study showed that the technique is vascularly safe as well as reproducible due to the use of conventional liposuction available to the vast majority of plastic surgeons.

REFERENCES

1. Kelly HA. Report of gynecological cases. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1899;10:197.

2. Saldanha O, Pinto E, Matos W, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty without undermining. Aesthet Surg J. 2001 Nov;21(6):518-526. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1067/maj.2001.121243

3. Saldanha OR, Pinto EBS, Matos Júnior WN, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty with selective and safe undermining. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003 Jul/Aug;27(4):322-7. PMID: 15058559 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-003-3016-z

4. Saldanha OR, Federico R, Daher PF, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009 Sep;124(3):934-42. PMID: 19730314 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b037e3

5. Pitanguy I. Abdominoplasty: classification and surgical techniques. Rev Bras Cir 1995;85:23-44.

6. Hoyos A, Perez ME, Guarin DE, Montenegro A. A report of 736 high-definition lipoabdominoplasties performed in conjunction with circumferential VASER liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Sep;142(3):662-675. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000004705

7. Baroudi R, Ferreira CA. Seroma: how to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesthet Surg J. 1998 Nov/Dec;18(6):439-41. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-820X(98)70073-1

8. Saltz R. Two position comprehensive approach to abdominoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2014 Oct;41(4):681-704. PMID: 25283455 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2014.07.008

9. Lockwood TE. Maximizing aesthetics in lateral-tension abdominoplasty and body lifts. Clin Plast Surg. 2004 Oct;31(4):523-37. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2004.04.001

10. Shiffman MA, Mirrafati S. Aesthetic surgery of the abdominal wall. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2005.

11. Duhrkoop D. Chiaroscuro in Painting: The Power of Light and Dark. 2007; [access in ANO mês DIA]. Available from: http://www.emptyeasel.com

12. Huger Junior WE. The anatomic rationale for abdominal lipectomy. Am Surg. 1979 Sep;45(9):612-7.

13. Matarasso A. Liposuction as an adjunct to a full abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995 Apr;95(5):829-36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199595050-00010

14. Matarasso A. Liposuction as an adjunct to a full abdominoplasty revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000 Oct;106(5):1197-1202;discussion:1203-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200010000-00035

15. Smith LF, Smith Junior LF. Safely combining abdominoplasty with aggressive abdominal liposuction based on perforator vessels: technique and a review of 300 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 May;135(5):1357-1366. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001200

16. Brauman D, Capocci J. Liposuction abdominoplasty: an advanced body contouring technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009 Nov;124(5):1685-95. PMID: 20009857 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b98c5d

17. Swanson E. Comparison of limited and full dissection abdominoplasty using laser fluorescence imaging to evaluate perfusion of the abdominal skin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Jul;136(1):31e-43e. PMID: 26111330 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001376

1. Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Leonardo Milanesi Possamai Rua Marquês do Pombal 450, Apartamento 304, Moinhos de Vento, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Zip Code: 90540-000. E-mail: leonardopossamai@hotmail.com

Article received: May 10, 2019.

Article accepted: July 8, 2019.

Institution: Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Conflitos de interesse: não há.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter