Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Comparative study of immediate implant and expander-implant reconstruction

Estudo comparativo entre reconstrução imediata com prótese versus abordagem expansor-prótese

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The benefits of immediate reconstruction have

been increasingly documented in the literature over the past few

years. Today, with some exceptions, immediate reconstruction

is the preferred surgical choice for breast cancer patients. In the

recent years, the number of reconstructions using expanders

and implants has increased.

Methods: This retrospective

study conducted between 2013 and 2014 included patients

undergoing mastectomy followed by breast reconstruction,

who were divided into direct implant reconstruction and

expander treatment groups. Several variables were evaluated.

Results: A total of 138 reconstructions (57 implants and 81

expander-implant) were performed. There were no intergroup

differences in postoperative complications. Radiotherapy

did not influence complications. Implant reconstruction

patients underwent fewer surgeries (1.78 vs 2.54) and

had fewer postoperative returns (8 vs 11.75).

Conclusion: Immediate implant and expander-implant reconstruction

approaches present low and similar postoperative complication

rates. Patients undergoing implant reconstruction had

a lower return rate and underwent fewer surgeries than

those undergoing expander-implant reconstruction.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms; Breast; Postoperative complications; Breast implant; Reconstruction.

RESUMO

Introdução: Ao longo dos últimos anos os benefícios das reconstruções imediatas se tornaram cada vez mais documentados na literatura e, hoje, o predomínio é pelas reconstruções imediatas. Nos últimos anos, o número de reconstruções com expansores e próteses tem aumentado.

Métodos: Estudo retrospectivo entre 2013 e 2014. Foram incluídas as pacientes submetidas à mastectomia, seguida de reconstrução de mama, e assim separadas em dois grupos: 1 - submetida a reconstrução direta com prótese e 2 - expansor. Diversos dados foram avaliados.

Resultados: Foram realizadas 138 reconstruções assim divididos: 57 com prótese e 81 com expansor-prótese. As complicações pós-operatórias não mostraram diferença entre os grupos. Radioterapia não teve influência nas complicações. Pacientes que fizeram reconstrução com prótese realizaram menos cirurgias (1,78 vs 2,54) e menos retornos pós-operatórios (8 vs 11,75).

Conclusão: As reconstruções imediatas com prótese ou expansor apresentam baixas e semelhantes taxas de complicações pós-operatórias. Pacientes submetidas às reconstruções com prótese tiveram menor taxa de retorno e número de cirurgias para finalizar a reconstrução.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias da mama; Mama; Complicações pós-operatórias; Implante mamário; Reconstrução

INTRODUCTION

For many years, breast reconstructions were performed late since it was believed that immediate breast repair could delay the onset of adjunctive therapy or prevent the diagnosis of future relapse. There was also great concern that this adjunctive therapy could increase the incidence of postoperative complications that could even lead to reconstruction loss. However, over the last few years, the benefits of immediate reconstruction have become increasingly clear and documented in the literature1,2,3.

Today, with some exceptions, immediate reconstruction is the preferred surgical choice for breast cancer patients. Many surgical breast reconstruction techniques are currently available. Despite being considered a long-term standard treatment4,5, autologous tissue reconstruction techniques are often not recommended due to classic contraindications, nonacceptance of donor-area morbidity by patients, longer recovery time, or patient comorbidities (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and morbid obesity). Patient profiles have been changing as cancer is diagnosed increasingly earlier in younger women with no children but a longer life expectancy. Simpler and faster recovery reconstructions were quickly accepted by these young women as the result resembles that of an aesthetic implant. Thus, we started saving more elaborate flaps for future procedures.

Implant reconstructions can be performed immediately, in which the prosthesis is inserted immediately after mastectomy, or in two steps, in which breast tissue expanders are used and subsequently replaced with implants.

A two-step reconstruction consists of placing a tissue expander immediately after mastectomy. The expansion continues until the optimal volume for a new surgical procedure is achieved. The expander is placed during the second procedure and an implant is placed simultaneously with breast symmetrization procedures such as mastopexy, reduction mammaplasty, or even a breast augmentation implant. The time interval between surgeries is variable, ranging from 3 months to over 1 year depending on adjunctive radiotherapy and chemotherapy and patient availability.

When possible, the use of an implant in the first surgery has some advantages, such as the easier use of tissues “virgin” to treatment, fewer postoperative returns, shorter convalescence time, and faster body image recovery.

The greater indication for nipple-areola complex (NAC)-sparing mastectomy has created a great opportunity for immediate direct reconstruction with an implant. In addition, the number of risk-reducing mastectomies has been increasingly growing, whether due to formal indications, BRCA gene mutation screening, or at patient request. These NAC-sparing prophylactic mastectomies are appropriate for this type of reconstruction since it is easier to achieve symmetry.

The main difficulty of immediate prosthetic reconstruction is limited adequate tissue coverage, which can lead to implant exposure, the need for several reoperations, and an inadequate aesthetic result. However, modern mastectomy techniques preserving the skin, pectoral muscle, and subcutaneous tissue have facilitated and improved the results of these reconstructions.

OBJECTIVE

To compare the results, advantages, and disadvantages of breast reconstruction with direct breast implant placement and two-step expander-implant reconstructions.

METHODS

This retrospective study was conducted from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2014 and followed the norms of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient signed an informed consent form. The study included all patients undergoing total mastectomy followed by immediate breast reconstruction using an implant or a temporary expander at private clinics belonging to the two main authors (Brasília-DF). The patients were divided into a group undergoing direct implant reconstruction and a group undergoing two-step expander-implant reconstruction.

Patients undergoing reconstructions using permanent expanders, local flaps, and autologous tissues (transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap or pectoralis major muscle flap); salvage reconstructions; and partial mastectomy were excluded.

Surgical technique

Both groups underwent the same surgical technique. After mastectomy, all patients underwent careful hemostasis testing, immediately following which a submuscular pocket was created for implant placement using the pectoralis major muscle and the anterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle and the anterior serratus muscle. After implant placement, the muscle pocket was closed with Vicryl 0 to completely cover the implant. All patients used a suction drain until a volume less than 50 mL was reached in 24 hours. Patients undergoing NAC-sparing immediate implant reconstruction did not use a postoperative bra to avoid NAC compression, decreasing vascularization. The remaining patients wore a bra from the first postoperative day. In expander reconstructions, expansion started during surgery if the pectoral muscle and/or flap conditions allowed. The remaining cases were treated in 2-3 postoperative weeks.

Data collection

Several data were collected. Demographic data such as age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, tumor type, and mastectomy type were used to evaluate the groups.

The analyzed complications included hematoma, seroma, minor infection (defined as cases of hyperemia in which the patient used antibiotics and the condition regressed), major infection (resulting in implant loss), capsular contracture, and necrosis (flap and/or NAC). Data such as postoperative return and number of surgeries were also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of the variable distribution. Normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test for independent samples and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Non-normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test and are presented as median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square (X2) or Fisher’s exact test and are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

During these 2 years of study, 102 of the surveyed patients were selected within the established criteria for a total of 138 reconstructions (57 immediate and 81 expander-implant). The mean patient age was 50.63 years for the immediate implant reconstruction group and 47.64 years for the expander-implant group (p = 0.188). Patients undergoing immediate implant reconstruction had lower mean BMI than those undergoing expander-implant reconstructions (23.4 vs 25.51; p = 0.006). The groups presented similar results for all other variables. The patients’ demographic data are presented in Table 1.

| Implant | Expander-implant | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 41 | 61 | |

| Laterality (n) | |||

| Unilateral | 25 | 41 | |

| Bilateral | 16 | 20 | 0,331 |

| Age, mean ± SD | 50,63 ±13 | 47,64 ±9,8 | 0,188 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 23,4 ±3,06 | 25,51 ±3,84 | 0,006* |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 (31,70% | 12 (19,67%) | 0,125 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (7,3%) | 5 (8,19%) | 0,592 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 4 (9,75%) | 5 (8,19%) | 0,525 |

| Former smoker, n (%) | 4 (9,75%) | 6 (9,83%) | 0,633 |

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 6 (14,63%) | 9 (14,75%) | 0,610 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 3 (7,31%) | 5 (8,19%) | 0,475 |

| COPD, n (%) | 2 (4,87%) | 0 | 0,159 |

| DVT (%) | 1 (2,43%) | 1 (1,63%) | 0,598 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 4 (12,19%) | 11 (18,03%) | 0,193 |

| NAC-sparing, n (%) | 20 (48,78%) | 19 (31,14%) | 0,056 |

| Histopathological | |||

| Absence of CA, n (%) | 2 (4,87%) | 0 | |

| IDC, n (%) | 27 (65,85%) | 34 (55,73%) | |

| DCIS, n (%) | 10 (24,39%) | 13 (21,31%) | |

| ILC, n (%) | 0 | 3 (4,91%) | 0,331 |

| LCIS, n (%) | 0 | 1 (1,63%) | |

| Lobular, n (%) | 1 (2,43%) | 5 (8,19%) | |

| Not described, n (%) | 1 (2,43%) | 6 (9,83%) | |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; NAC, nipple–areola complex; IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ

* Statistically significant.

Many postoperative complication variables were evaluated, but no intergroup difference was noted in minor and major infections, hematomas, seromas, contractures, or necrosis rates. Data on postoperative complications are presented in Table 2.

| Reconstruction technique | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Implant reconstruction (n = 57) | Expander (n = 81) | p | |

| Complications | |||

| Hematoma, n (%) | 2 (3,5%) | 1 (1,23%) | 0,367 |

| Seroma, n (%) | 11 (19,29%) | 16 (19,75%) | 0,947 |

| Minor Infection, n (%) | 6 (10,52%%) | 11 (13,58%) | 0,591 |

| Major infection, n (%) | 3 (5,26%) | 3 (3,7%) | 0,658 |

| Necrosis, n (%) | 7 (12,28%) | 8 (9,87%) | 0,655 |

| Contratura (%) | 4 (7%) | 5 (6,17%) | 0,843 |

Postoperative complications in both groups were also evaluated for exposure to radiotherapy. The individual analysis by reconstruction type showed that radiotherapy did not influence capsular contracture complications (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 5 shows the number of breast reconstructions completed using each technique and the number of surgeries required to achieve this outcome. The patients undergoing immediate implant reconstruction required fewer surgeries to achieve treatment completion than the patients undergoing expander-implant reconstruction (1.78 ± 0.55 vs 2.54 ± 0.72; p < 001).

| Implant reconstruction |

Expander | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of surgeries, mean ± SD | 1,78 +- 0,55 | 2,54 +- 0,72 | <0,001* |

* Statistically significant

The mean implant volume used in the immediate implant reconstruction group was 357.92 mL.

Table 6 shows the number of postoperative returns for both reconstruction techniques. Patients undergoing immediate implant reconstruction required fewer postoperative returns than those undergoing expander-implant reconstruction (8 ± 3.26 vs 11.75 ± 4.7; p < 0.001).

| Implant reconstruction |

Expander | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Returns, mean ± SD | 8 +- 3,26 | 11,75 +- 4,7 | < 0,001* |

* Statistically significant

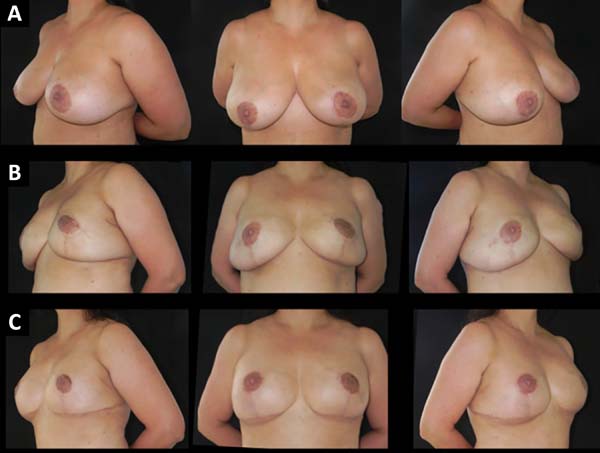

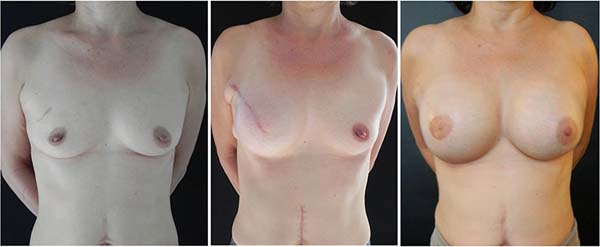

Figures 1-5 show the immediate breast reconstruction cases. Figures 1, 2, and 3 show the implant breast reconstructions, while Figures 4 and 5 show the expander-implant reconstructions.

DISCUSSION

Breast cancer is a major public health problem worldwide, with over 1.5 million new cases in 2012 alone6. The US spent approximately USD 14 billion in 2006 in addition to USD 12 billion due to the resultant loss of productivity7. Breast reconstruction is a vital step in treating these patients since it restores body image and, consequently, improves personal and psychological satisfaction8,9,10,11.

Several breast reconstruction techniques have evolved over the last few years with the objective of achieving more natural reconstructions with greater overall patient satisfaction in as few surgeries as possible.

Implant reconstructions have become common worldwide12. They have been increasingly indicated in the US, especially after the advent of dermal matrices12,13. Modern mastectomy techniques that promote better skin preservation with the use of skin- or NAC-sparing mastectomies enabled immediate implant placement after a mastectomy and are increasingly accepted by patients, especially those who do not wish to undergo several surgical procedures or the postoperative expansion process. However, several risks are associated with this technique due to total dependence on mastectomy flap quality and difficulty adjusting volume.

Patients undergoing immediate implant and two-step expander-implant reconstruction were evaluated in this study. The groups presented similar values except for mean BMI, which was higher in the expander-implant group. However, this difference, although significant (p = 0.006), differed little between groups when evaluated by the BMI classification, which considers patients with a BMI of 18.5-24.9 as eutrophic (normal weight) and those with a BMI of 25-29.9 as overweight. The patients in the expander-implant group had a mean BMI of 25.51 kg/m2, very close to the eutrophic classification (normal weight).

The evaluation of postoperative complications presented no statistically significant intergroup differences, showing that both techniques are extremely safe and comparable when performed with clinical judgment and good patient selection. These data are corroborated by several published studies7,14.

Some studies show that expander-implant reconstruction has some advantages over implant reconstruction6,14, especially the possibility of adjusting breast volume by placing a larger implant and correcting minor imperfections during the second surgery, such as implant pocket and mammary groove adjustments. However, this was not seen in the present study.

In this study, the implant volume in immediate reconstructions ranged from 225 cc to 495 cc, with a mean of 357.92 cc. The number of surgeries required to complete reconstruction was also evaluated. Patients undergoing immediate implant reconstruction underwent fewer surgeries than those undergoing expander-implant reconstruction (1.78 vs 2.54; p ≤ 0.001). Also, there were fewer postoperative returns in the immediate implant reconstruction group than in the expander-implant group (8 vs 11.75; p < 0.001).

These results have several implications. First, when well indicated, immediate implant reconstruction can result in complete reconstruction with one procedure, with fewer postoperative returns, fewer surgeries, and less stress for the patient, who can return sooner to their daily activities, among other implications. Additionally, even in cases in which a new surgery is required, this new procedure is usually shorter, faster, and has no influence on the patient’s overall satisfaction, as observed in a study by Susarla et al. (2015)14.

Therefore, immediate implant and expander-implant reconstructions are viable, are safe, have accurate indications, and should be options for breast reconstruction.

It is important to inform patients that immediate implant reconstruction will not definitely result in complete reconstruction in a single procedure, although it is possible. This technique depends on several factors already mentioned (mastectomy quality and pectoral muscle viability, which can only be analyzed intraoperatively) and sometime may not be possible. In such cases, the surgeon will need to use an expander.

This study’s retrospective nature created a limitation. Cost is also an important factor to be evaluated in future studies, although it was not the objective of our study.

CONCLUSION

Immediate implant and expander-implant reconstructions presented similar low postoperative complication rates. Immediate implant reconstruction patients undergo fewer surgeries to achieve the final outcome and have fewer postoperative returns.

COLLABORATIONS

|

MCC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

AB |

Final manuscript approval, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

RQL |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

CMA |

Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

FTM |

Formal Analysis |

|

IRJ |

Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

LGM |

Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

JCD |

Writing - Review & Editing |

REFERENCES

1. Durand JC, Pilleron JP. Breast cancer: Limited excision followed by irradiation-Results and therapeutic indications in 150 cases treated at the Curie Foundation in 1960 -1970. Bull Cancer 1977;64:611-618.

2. Singletary SE. Skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction: The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:411-416 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02305673

3. Roostaeian J, Pavone L, Da Lio A, Lipa J, Festekjian J, Crisera C. Immediate Placement of implants in breast reconstruction: patient selection and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg:127,4: 1407-1415. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318208d0ea

4. Pomahac B, Recht A, May JW, Hergrueter CA, Slavin SA. New trends in breast cancer management: Is the era of immediate breast reconstruction changing? Ann Surg. 2006;244: 282-288.

5. Bodin F, Zink S, Lutz JC, Kadoch V, Wilk A, Bruant-Rodier C. Which breast reconstruction procedure provides the best long-term satisfaction (in French)? Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2010;55:547-552.

6. Davila AA, Mioton LM, Chow G, Wang E, Merkow RP, Bilimoria KY, et.al Immediate two-stage tissue expander breast reconstruction compared with one-stage permanent implant breast reconstruction: A multi-institutional comparison of short-term complications. J Plast Surg Hand Surg, 2013;344-349. PMID: 23547540 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/2000656X.2013.767202

7. Navin Singh, Nancy L. Reaven, Susa E. Funk. Immediate 1-stage vs. tissue expander postmastectomoy implant breast reconstructions: A retrospective real-world comparison over 18 months. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive$ Aesthetic Surgery, 2012: 65, 917-923. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2011.12.040

8. Elder EE, Brandberg Y, Bjorklund T, Raylander R, Largergren J, Jurell G, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction in breast cancer patients after immediate reconstruction: A prospective study. Breast 2005;14:201-208. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2004.10.008

9. Rowland JH, Holland JC, Chaglassian T, Kinne D. Psychological response to breast reconstruction: Expectations for and impact on postmastectomy functioning. Psychosomatics 1993;34:241-250. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71886-1

10. Rosenqvist S, Sandelin K, Wickman M. Patient’s psychological and cosmetic experience after immediate breast reconstruction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1996;22:262-266.

11. Brandberg Y, Malm M, Blomqvist L. A prospective and randomized study, “SVEA,” comparing effects of three methods for delayed breast reconstruction on quality of life, patient-defined problem areas of life, and cosmetic result. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:66-74; discussion 75-76 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200001000-00011

12. Cassileth L, Kohanzadeh S, Amersi F. One-stage immediate Breast Reconstruction with implants. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2012;69,2. PMID: 21734545 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182250c60

13. Zohng T, Oberle C.T, Hofer S, Beber B et.al The Multi Centre Canadian Acelluar Dermal Matrix Trial (MCCAT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial in implant-based breast reconstruction. Trials 2013, 14:356.

14. Susarla S, Ganske I, Morris D, Erisksson E, Chun Y. Comparison of Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction in immediate single-stage versus two-stage implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015; 135,1; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000000803

1. Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Brasília, DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Marcela Caetano Cammarota SMH/N, Quadra 2, Bloco C, Edifício Dr. Crispim, Sala 1315, Asa Norte, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Zip Code: 70710-149. E-mail: marcelacammarota@yahoo.com.br

Article received: February 17, 2019.

Article accepted: April 18, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter