Case Report - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Eagle syndrome: a case report

Síndrome de Eagle: relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Eagle syndrome is a rare condition, and its etiology has not yet been well established and its correct treatment is uncertain. Its treatment must be defined together with the patient, be it conservative or surgical, always taking into consideration the patient's expectations, in addition to a solid professional expertise in the modality chosen for the treatment. In this article, we present the case of a 35-year-old patient who was admitted to the Felício Rocho Hospital and discuss the various aspects of the disease, including the treatment modality chosen for the case.

Keywords: Cervicalgia; Facial pain; Ligament; Case report; Operative surgical procedure

RESUMO

A síndrome de Eagle é uma condição rara e com etiologia ainda não bem estabelecida, a qual se deve ter bastante suspeição para seu correto tratamento. Seu tratamento deve ser definido em conjunto com o paciente, seja ele conservador ou cirúrgico, sempre levando em consideração as expectativas do paciente, além da maior expertise do profissional na modalidade escolhida para o tratamento. Neste artigo, apresentamos uma paciente de 35 anos atendida no Hospital Felício Rocho, discutindo os diversos aspectos da doença, inclusive a modalidade de tratamento escolhida para o caso.

Palavras-chave: Cervicalgia; Dor facial; Ligamentos; Relatos de casos; Procedimentos cirúrgicos operatórios

INTRODUCTION

The styloid process (SP) is a protrusion of the temporal bone in the inferior, anterior, and medial directions. It is located between the angle of the mandible and the mastoid process, posterior to the tonsillar fossa and laterally to the pharynx. It has an anatomic relationship with the carotid arteries, internal jugular vein, and facial, glossopharyngeal, vagus, and hypoglossal nerves1,2.

Eagle syndrome is defined as a rare condition of SP symptomatic elongation (length, >2.5 cm) or mineralization of the stylohyoid or stylomandibular ligaments2. In 1937, the otolaryngologist Watt Weems Eagle described the syndrome, having reported >200 cases1,2. Its incidence ranges from 1.4% to 30%, affecting more women than men, with ages ranging from 20 to 40 years. Bilateral stretching is common, but bilateral symptomatology is uncommon1-5.

Its etiology is not totally known, and some hypotheses have been accepted, including congenital origin, partial/complete calcification of the stylohyoid ligament, trauma followed by reactive hyperplasia, metaplasia of the remnants of the second branchial arch.2

Symptoms are nonspecific, such as pharyngeal globus sensation (55%), recurrent sore throat (40%), bilateral reflex otalgia (40%), headache (25%), carotidynia (20%), reduction of cervical mobility, and pain when opening the mouth. The symptoms appear or worsen on swallowing, chewing, tongue movements, rotation of the head, or palpation of the tonsillar fossa. They are non-specific and may be confused by other conditions such as myofascial pain, dental origin, and temporomandibular joint.2,4,5

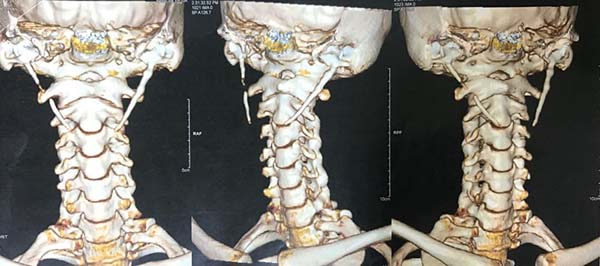

The diagnosis is based on the patient’s detailed medical history. In propaedeutics, radiography is a limited resource owing to the possibility of overlapping images. The gold standard is computed tomography with three-dimensional (3-D) reconstruction, which provides detailed anatomy of the region, enabling surgical programming. Another form of diagnostic suspicion is the temporary improvement of pain after local anesthesia, with return of the symptomatology after the end of the anesthetic effect1,2,6,7.

Different approaches are available for the treatment of the syndrome, including pharmacological or surgical approaches, or a combination of both. Conservative treatment can be performed with physiotherapy, analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, and even local infiltration with an anesthetic associated with hydrocortisone1-4,7-9. However, some patients require surgical intervention to improve the condition, which can be performed either intraorally or transcervically.

Finally, the follow-up duration is not yet well established. They range from weekly to monthly consultations, with progressive spacing between them.

CASE REPORT

E.L.C., a 35-year-old female patient, visited the plastic surgery service at the Felício Rocho Hospital in Belo Horizonte, MG, after consulting with different health experts, without success. She had a complaint of bilateral cervicalgia for 3 years, mainly in the left side, associated with headache and foreign body sensation in the pharynx. She also reported worsening of symptoms during mouth opening and swallowing, with partial improvement after simple analgesia, without complete remission of symptoms. She had a cerebral neoplasia in the right frontotemporal cerebral transition and underwent a subsequent surgical resection. She denied previous oropharyngeal surgeries but had been taking numerous medications, including anticonvulsants and potent analgesics.

On computed tomography (CT) of the neck with 3-D reconstruction (Figures 1 and 2), calcifications of the bilateral stylohyoid ligaments were observed, which were more evident on the left, raising the suspicion of Eagle syndrome.

Thus, considering the relapse of the symptomatology despite the routine use of drugs (without total success), surgical intervention was decided together with the patient. The patient was advised about the risks and benefits of the invasive treatment.

In March 2018, the patient underwent bilateral exploratory cervicotomy under general anesthesia, with resection of approximately 3 cm of calcified stylohyoid ligaments (Figures 3 to 7). He evolved without surgical complications, with monthly elective follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The Eagle syndrome is a rare condition with many uncertainties, which makes most patients seek several professionals, as the patient reported, before the diagnosis is established.

During its description, Eagle observed two types of syndrome as follows: (1) classical syndrome, characterized by pharyngeal globus, dysphagia, odynophagia, ipsilateral reflex otalgia, or retromandibular pain, usually initiated after a tonsillectomy secondary to local trauma; and (2) carotid artery syndrome, which occurs independently of previous surgeries in the region, caused by local mechanical irritation, with consequent stimulation of the sympathetic plexus of the carotid arteries. Although two syndromic spectra are defined, in some cases, like the present case, overlapping spectra may be observed, which are often erroneously diagnosed as head and neck disorders.

For propaedeutics, a CT was requested with 3-D reconstruction, as it was the gold standard. This examination allowed us to visualize the elongation of the styloid process and the calcification of the stylohyoid ligaments, in addition to the planned surgical approach.

Regarding the treatment, it should be defined together with the patient, be it conservative or surgical, always considering the greater expertise of the professional in the modality chosen for the treatment, in addition to respecting the patient’s expectations. When a surgical technique is opted for, it may be performed intraorally or transcervically. In this case, we opted for the transcervical surgical approach, a decision made by the surgeon and the patient together after weighing the risks and benefits of the technique.

This has the advantages of adequate exposure of the cervical structures, with consequent satisfactory excision of the styloid, better control of possible vascular lesions, and less blood loss, besides being a sterile technique. However, aesthetic deformity is found to be the main disadvantage; in addition to longer surgical time, cutaneous paresthesia can occur and general anesthesia may be necessary1-3.

Finally, the follow-up duration is still variable. Some authors perform weekly follow-up for 2 months, biweekly for the next 2 months, and monthly for other months, while others perform follow-up only in the first 2 months, with discharge after this period. Our proposal was to perform monthly follow-up of the patient from the first return2.

COLLABORATIONS

|

HBF |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, data curation, final manuscript approval, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

SMC |

Conception and design study, conceptualization, final manuscript approval, supervision, writing - review & editing. |

|

LCJ |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, data curation, final manuscript approval, formal analysis, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Fini G, Gasparini G, Filippini F, Becelli R, Marcotullio D. The long styloid process syndrome or Eagle’s syndrome. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28(2):123-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1054/jcms.2000.0128

2. Chrcanovic BR, Custódio AL, de Oliveira DR. An intraoral surgical approach to the styloid process in Eagle’s syndrome. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;13(3):145-51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-009-0164-6

3. Petrović B, Radak D, Kostić V, Covicković-Sternić N. Styloid syndrome: a review of literature. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2008;136(11-12):667-74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2298/SARH0812667P

4. Martins WD, Ribas Mde O, Bisinelli J, França BH, Martins G. Eagle’s syndrome: treatment by intraoral bilateral resection of the ossified stylohyoid ligament. A review and report of two cases. Cranio. 2013;31(3):226-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1179/crn.2013.033

5. Li S, Blatt N, Jacob J, Gupta N, Kumar Y, Smith S. Provoked Eagle syndrome after dental procedure: A review of the literature. Neuroradiol J. 2018;31(4):426-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1971400917715881

6. Kamal A, Nazir R, Usman M, Salam BU, Sana F. Eagle syndrome; radiological evaluation and management. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64(11):1315-7.

7. Esiobu PC, Yoo MJ, Kirkham EM, Zierler RE, Starnes BW, Sweet MP. The role of vascular laboratory in the management of Eagle syndrome. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2018;4(1):41-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvscit.2017.12.009

8. Chen R, Liang F, Han P, Cai Q, Yu S, Huang X. Endoscope-Assisted Resection of Elongated Styloid Process Through a Retroauricular Incision: A Novel Surgical Approach to Eagle Syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(7):1442-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2017.01.016

9. Papadiochos I, Papadiouchou S, Sarivalasis ES, Goutzanis L, Petsinis V. Treatment of Eagle syndrome with transcervical approach secondary to a failed intraoral attempt: Surgical technique and literature review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;118(6):353-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jormas.2017.06.017

1. Hospital Felício Rocho, Belo Horizonte, MG,

Brazil.

2. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

3. ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE CIRURGIA

CRÂNIO-MAXILO-FACIAL, SÃO PAULO, SP, BRAZIL.

Corresponding author: Henrique Beletáble Fonseca, Rua Rio Grande do Sul, 1285, apto 602 B, Santo Agostinho, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, Zip Code: 30170-111. E-mail: henriquebeletablef@gmail.com

Article received: September 18, 2018.

Article accepted: November 11, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter