Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Coverage of the lower third of the limb and foot injuries using reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap described by Carriquiry

Cobertura de lesões em pé e terço inferior da perna com retalho fasciocutâneo reverso da panturrilha (Carriquiry)

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Skin grafts are not effective to cover lesions in the distal third of the lower limbs that expose the bones, joints, tendons, and blood vessels due to a limited vascular bed and poor granulation of the wounds. These lesions can only be corrected with microsurgical transfer or muscle, myocutaneous, or fasciocutaneous flaps.

Methods: The lower border of the flap was marked 5 cm above the malleolus. The upper border was marked after providing sufficient length for complete coverage of the lesion. The incision was performed at the marked upper border, and the skin and subcutaneous tissue were elevated together with muscle fascia. The sural nerve was preserved in its original bed. The flap was lifted to the marked lower border (the pedicle). At this point, the flap was transposed at a sufficient angle to cover the lesion.

Results: Eight cases of surgery were conducted using the flap described above. All cases had exposed bones and tendons in the distal region of the limb, back of the foot, or both, in which the reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap with the technique proposed by Carriquiry was used. The cases showed satisfactory esthetic and functional results.

Conclusion: The used flap can correct lesions of the lower third of the limbs and foot. It is relatively easy to make, with good vascular supply, and there is no functional loss of the donor area.

Keywords: Reconstructive surgical procedures; Leg injuries ; Foot injuries; Surgical flaps; Sural nerve

RESUMO

Introdução: Lesões no terço distal dos membros inferiores, com exposição de ossos,

articulações, tendões e vasos sanguíneos, não são passíveis do uso de

enxertos de pele. Isto ocorre porque o leito vascular é exíguo e pela pobre

granulação das feridas, podendo apenas ser corrigidas com retalhos

musculares, miocutâneos, fasciocutâneos ou transferência microcirúrgica.

Métodos: O retalho em seu limite inferior é demarcado a partir de 5cm acima dos

maléolos. Superiormente, é marcado num comprimento suficiente para cobertura

total da lesão. Realizada incisão em demarcação prévia, e elevados pele e

tecido subcutâneo juntamente com a fáscia muscular. O nervo sural é

preservado em seu leito original. A elevação do retalho se dá até o ponto

inferior marcado (o pedículo). Neste ponto, o retalho é transposto numa

angulação suficiente para alcançar a lesão.

Resultados: Oito casos foram operados utilizando o retalho descrito. Todos apresentavam

exposição de ossos e tendões em região distal da perna, dorso do pé ou

ambos, nos quais foram utilizados o retalho fasciocutâneo reverso da perna

com a técnica proposta por Carriquiry. Os casos apresentaram resultados

estético e funcional satisfatórios.

Conclusão: O retalho utilizado se presta à correção de lesões do terço inferior da perna

e do pé. É relativamente fácil de ser confeccionado, com bom suprimento

vascular, e não há perda funcional do leito doador.

Palavras-chave: Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Traumatismos da perna; Traumatismos do pé; Retalhos cirúrgicos; Nervo sural

INTRODUCTION

Skin grafts are not effective in covering the lesions in the distal third of the lower limbs that expose the bones, joints, tendons, and blood vessels due to a limited vascular bed and poor granulation of the wounds. These lesions can only be corrected with microsurgical transfer, muscle, myocutaneous, or fasciocutaneous flaps1-3.

Adequate protection of these structures with minimal sequelae in the donor area and constant vascularization are some of the factors that have been considered for ideal coverage. The main limiting factors are the dimensions, depth of the lesion, and presence of osteomyelitis4. The reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap should consider two principles: the length × width ratio of the flap and that the flap should be based on a proximal pedicle5.

Since 1980s, with a good understanding of the anatomy of the lower limbs and improvement of myocutaneous flaps, several techniques have been proposed to reconstruct the distal third of the lower limbs. In 1983, Pontén described the larger leg flaps with inclusion of the fascia. In the same year, Donski & Fogdestam proposed the distal pedicle fasciocutaneous flap based on the fibular artery. The reverse fasciofat flap based on perforating branches of the posterior tibial artery was described by Gumener et al. in 1990 for reconstruction of the malleolar and calcaneal regions, accompanied by primary closure of the donor area6. Additionally, in 1990, Carriquiry5 proposed a reverse fasciocutaneous flap based on two blood supplies, myocutaneous and septocutaneous perforators (from the fibular and posterior tibial arteries), isolating and preserving the sural nerve and medial superficial sural artery that accompanies the sural nerve. In 1992, Masquelet et al. described the reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap based on the sural neurovascular pedicle5.

OBJECTIVE

To demonstrate the feasibility of the reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap described by Carriquiry to cover the lower third of the limbs and foot injuries.

METHODS

Surgery was performed in eight patients admitted to the Hospital de Base de São José do Rio Preto, SP, in the Plastic Surgery Service of FAMERP/FUNFARME, from 2013 to 2018. All patients had lesions that exposed the bones and tendons in the distal region of the limbs, dorsum of the foot, or both, and the reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap was used with the technique proposed by Carriquiry in 1990. The study protocol followed the principles of Helsinki Declaration.

Regional anatomy

The skin, subcutaneous cellular tissue, and muscular fascia of the calf are extensively vascularized. The dense suprafascial vascular plexus, which has the main anastomoses oriented longitudinally, and the rich septocutaneous perforator system, together with the well-known and widely used musculocutaneous and axial systems, contribute to the creation of safe fasciocutaneous flaps in this region5.

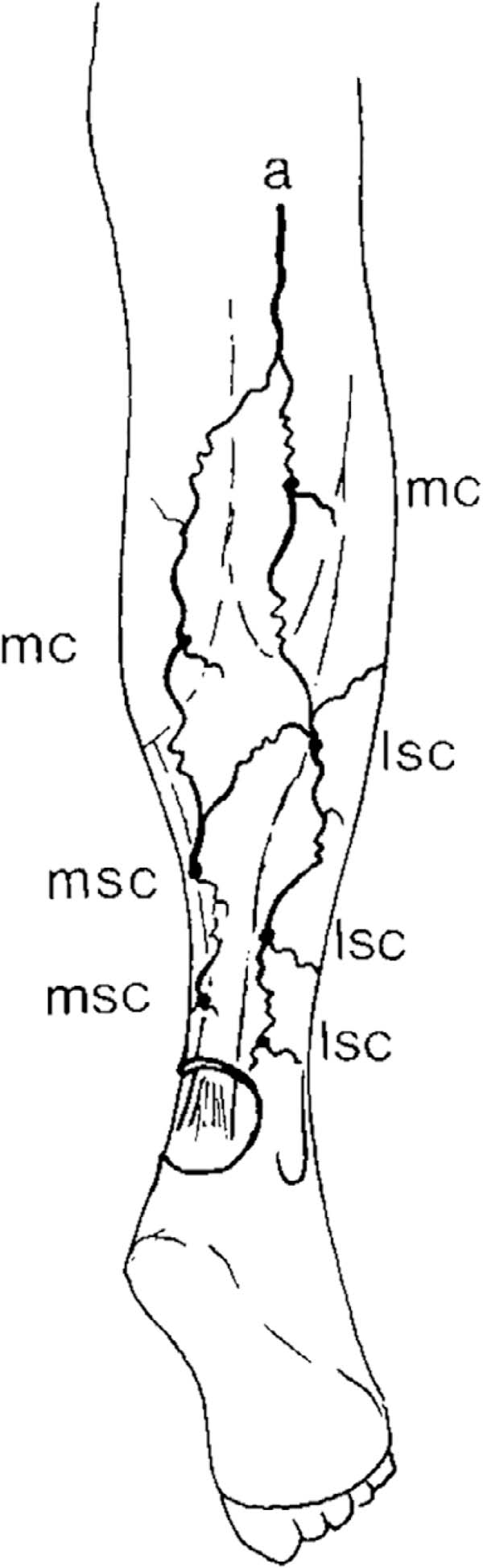

The flap described by Carriquiry is based on the medial and lateral septocutaneous arteries of the posterior limb that anastomose with each other and with the superficial sural artery through longitudinally-oriented suprafascial arches5 (Figure 1).

The most significant input to the suprafascial plexus in the lower half of the limb comes from the septocutaneous system, as the axial vessels do not reach such distal regions and musculocutaneous perforators are infrequent at this level5.

Therefore, the blood is supplied via the distal septocutaneous vessels through longitudinal anastomoses in the suprafascial plexus during the elevation of distal fasciocutaneous flaps5.

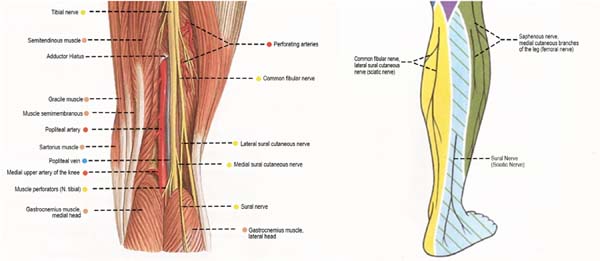

In the popliteal fossa, the tibial nerve gives rise to the medial sural cutaneous nerve, which joins the lateral sural cutaneous nerve from the common fibular nerve to form the sural nerve. This nerve supplies the skin on the posterior and lateral sides of the limbs and the lateral side of the ankle and foot, and it should be preserved to maintain the sensitivity of this region7 (Figure 2). The flap described in this study preserves the sural nerve in its original bed, maintaining its sensory function.

Surgical technique

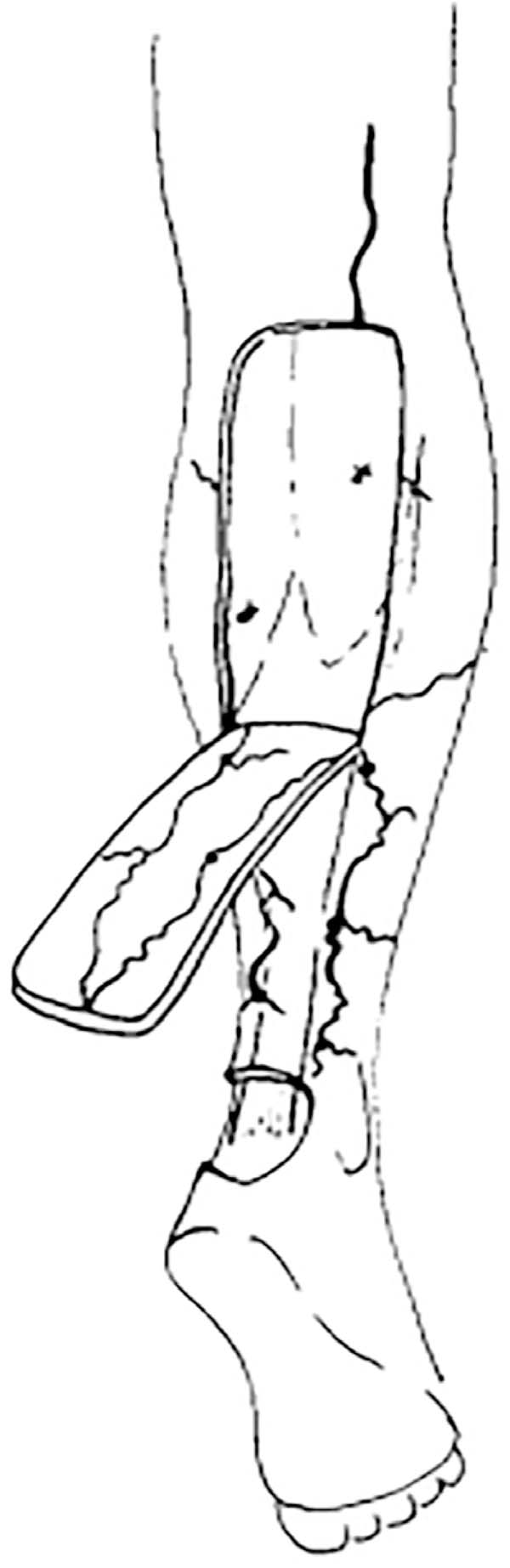

The lower border of the flap was marked 5 cm above the lateral and medial malleoli (the pivot point of rotation). The upper border was marked after providing a sufficient length for the complete coverage of the lesion, which corresponds to the distance from the pedicle of the flap to the most distal point of the lesion, also considering the required rotation to cover the lesion; this distance is the length of the flap. The incision was performed in the marked upper border, and the skin and subcutaneous tissue were elevated together with the muscle fascia.

Approximately 1 cm should be preserved on either side of the lateral borders of the Achilles tendon, as the medial and lateral septocutaneous arteries of the posterior region of the limbs emerge in that region. The sural nerve was preserved in its original bed and subsequently placed between the gastrocnemius muscles and covered by them to prevent their exposure. The flap was elevated to the marked lower point-the pivot-in the lower third of the limb (Figure 3).

At this point, the flap was transposed at a sufficient angle to reach the lesion (approximately 150°). It is not necessary to maintain the fasciosubcutaneous border beyond the skin island, and the subcutaneous tissue and fascia can have the same size as the cutaneous portion of the flap. Three weeks after this first step, the flap was released (sufficient size to keep the lesion covered), and its other part was returned to the donor bed. At this time, full-thickness skin grafts from the inguinal region were also used to cover the donor area of the flap.

RESULTS

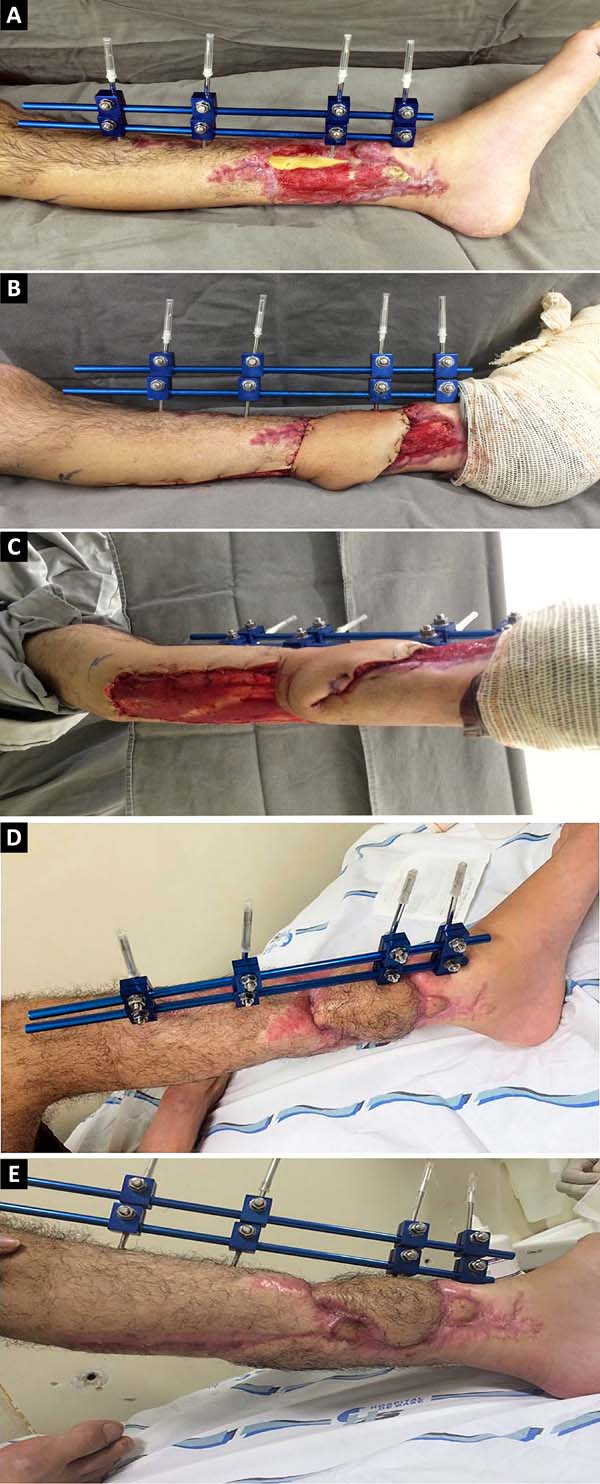

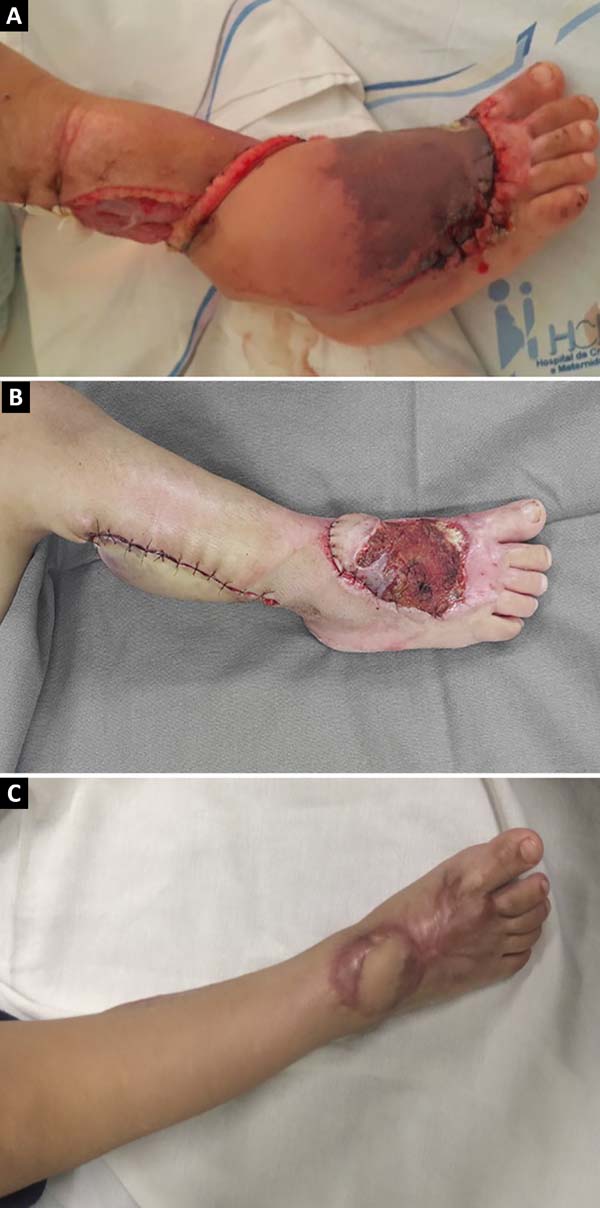

The surgical procedures performed using the technique described by Carriquiry showed satisfactory functional results (Figures 4-6).

To achieve these results, care was taken in the management of these patients, such as 1) pedicle care to ensure that there was no tapering, twisting, or compression, both intraoperatively and in the postoperative period; 2) identification of the medial sural nerve so that it remained in its original topography and was not sectioned or dissected together with the flap; 3) stimulation of venous drainage through retrograde massage of the flap; and 4) immobilization of the ankle joint.

Only one case showed complications in the postoperative period, evolving with ischemia and superficial skin necrosis in the distal portion of the flap, which was resolved with debridement and grafting of the skin posteriorly (Figure 7). The other cases showed satisfactory progression with total coverage of the lesions.

DISCUSSION

The distal third of the lower limb is often exposed to trauma. Thus, it is difficult to reconstruct this region when skin coverage is necessary 6. Accidents with motorcycles are the main source of these injuries9. Out of the eight cases in this study, five were caused by this type of trauma.

It is always difficult to cover this region with skin. In this segment, there is no interposition of the muscular tissues between the noble structures and integument; thus, it has limited distensibility and mobility. Therefore, the use of skin grafts and random rotation flaps is inadequate for wounds that affect the full thickness of the skin10. In these cases, it is necessary to use distant flaps, which can be fasciocutaneous or free11.

The reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap described by Carriquiry is easy to use, reliable, and allows for simple postoperative care. It has a wide rotation angle (up to 150°) without a large pedicle volume. Special care should be taken in the subdermal dissection of the pedicle to minimize the final esthetic sequelae. Although similar to the reverse-flow sural flap, the main difference is the preservation of the sural nerve, thereby maintaining its sensory function. It also differs as the fasciosubcutaneous border does not need to be maintained beyond the skin island, and the lateral borders of the Achilles tendon need to be preserved, not only the region near the lateral malleolus as in the sural flap.

The reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap is a good alternative to microsurgical flaps, which are highly complex and technically difficult, have a high hospital cost, and a lengthy surgical time (mean of 8 hours)12.

However, the use of these flaps is contraindicated in cases of previous trauma in the medial or lateral region of the limbs that affect the pedicle of the flap, since this compromises its vascularization5.

In the present study, this flap was used in lesions located in the distal region of the limbs and dorsum of the foot that exposed the bones and tendons, including an exposed fracture or tendon injury.

CONCLUSION

The flap used in this study corrects lesions of the lower third of the limbs and foot. It is relatively easy to prepare, with a good vascular supply, based on more than one pedicle and without functional loss of the donor bed. As disadvantages, there is the necessity to perform more than one procedure and final thickness of the lesion and the donor area changes.

COLLABORATIONS

|

CGS |

Conception and design study, data curation, methodology, project administration, realization of operations and/or trials, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

AMR |

Realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

LAFK |

Conception and design study, data curation, realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

CCF |

Realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

VBC |

Realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

ARB |

Final manuscript approval, supervision, writing - review & editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Kneser U, Bach AD, Polykandriotis E, Koop J, Horch RE. Delayed reverse sural flap for staged reconstruction of the foot and lower leg. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(7):1910-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000189204.71906.c2

2. Touam C, Rostoucher P, Bhatia A, Oberlin C. Comparative study of two series of distally based fasciocutaneous flaps for coverage of the lower one-fourth of the leg, the ankle, and the foot. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(2):383-92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200102000-00013

3. Donski P, Fogdestam I. Distally based fasciocutaneous flap from the sural region. A preliminary report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;17(3):191-6. PMID: 6673085

4. Attinger A, Cooper P. Soft tissue reconstruction for calcaneal fractures or osteomyelitis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32(1):135-70. PMID: 11465125

5. Carriquiry CE. Heel coverage with a deepithelialized distally based fasciocutaneous flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85(1):116-9. PMID: 2293720 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199001000-00022

6. Braga-Silva J, Martins PDE, Román JA, Gehlen D. Utilização do Retalho Adipofascial Reverso nas Perdas de Substância Cutânea do Terço Distal da Perna e Pé. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plást. 2005;20(3):182-6.

7. Moore KL, Dalley AF. Anatomia orientada para a clínica. 5a ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2007.

8. Sobotta J, Waschke J. Sobotta Atlas de Anatomia Humana. 23a ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2012.

9. Motoki THC, Carvalho KC, Vendramin FS. Perfil de pacientes vítimas de trauma em membro inferior atendidos pela equipe de cirurgia reparadora do Hospital Metropolitano de Urgência e Emergência. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(2):276-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752013000200018

10. Rezende MR, Rabelo NTA, Benabou JE, Wei TH, Mattar Junior R, Zumiotti AV, et al. Cobertura do terço distal da perna com retalhos de perfurantes pediculados. Acta Ortop Bras. 2008;16(4):223-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-78522008000400007

11. Quirino AC, Viegas C. Retalhos fasciocutâneos para cobertura de lesões no pé e tornozelo. Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49(2):183-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbo.2014.01.017

12. Souza Filho MVP, Santos CC. Microcirurgia em reconstruções complexas: análise dos resultados e complicações. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(2):123-30.

1. Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto,

São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil.

2. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Camila Garcia Sommer, Avenida Brigadeiro Faria Lima 5544, Vila São Manoel, São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil. Zip Code 15090-000. E-mail: camisommer@hotmail.com

Article received: November 12, 2018.

Article accepted: April 21, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter