Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Validation of the Portuguese version of the Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire

Validação para a língua portuguesa do Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ)

ABSTRACT

Currently, the Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ) is the only quality-of-life questionnaire specific for the assessment of trismus. The disease, characterized by limited mouth opening, impairs usual activities such as eating, swallowing, talking, and performing oral hygiene, causing great discomfort to patients. Translation of quality-of-life questionnaires plays an important role in promoting health awareness in the populations of different countries. This study aimed to validate the Portuguese version of the GTQ to allow its effective application in Portuguesespeaking populations. The Portuguese version of the GTQ was successfully validated through the following steps: translation, back translation, cultural adaptation, and revalidation.

Keywords: Trismus; Quality-of-life; Validation study; Translation; Patient health questionnaire

RESUMO

Atualmente, o Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ) é o único questionário de qualidade de vida específico sobre trismo. A afecção, definida como restrição à abertura da boca, gera prejuízo a atividades habituais como comer, engolir, falar e fazer a higiene oral, trazendo grande desconforto aos pacientes. A tradução de questionários de qualidade de vida desempenha um importante papel no conhecimento da saúde das populações nos diferentes países. O objetivo do presente estudo é apresentar a validação do GTQ para a língua portuguesa, a fim de permitir sua aplicação efetiva nas populações de idioma português. O GTQ foi validado com sucesso para a língua portuguesa conforme os seguintes passos: Tradução, Retradução (back translation), Adaptação cultural e Revalidação.

Palavras-chave: Trismo; Qualidade de vida; Estudos de validação; Tradução; Questionário de saúde do paciente; Trismus; Quality-of-life; Validation study; Translation; Patient health questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

The term trismus was originally only used for describing the incapacity of patients with tetanus to open their mouths. Currently, it has been widely used to describe any type of restriction in mouth opening after trauma, muscle diseases, or neoplasms, triggered by a primary lesion resulting from surgical procedures or radiotherapy1,2. The diagnosis of trismus should be based on objective criteria. The measurement of the mouth opening with a millimeter ruler between the upper and lower central incisors at the maximum opening is the most frequently used measurement.

Adults with measurements of < 35 mm are considered as having trismus by most authors1,3-8. The subjective diagnosis based on the clinical complaint of patients, such as difficulty in mouth opening, mouth locking, and muscle stiffness, should be considered but is less reliable from the scientific point of view6,7,9,10.

The impact of limited mouth opening on quality-of-life is considered relevant. However, subjective information loses value when this symptom is analyzed in the general context of treatment outcomes. According to Vartanian et al.11, the subjective concept of quality-of-life should be transformed into a quantitative measure so that it can be used both clinically and in research. To this end, questionnaires for assessing quality-of-life are widely used, and the greater the dissemination and administration of standardized questionnaires, the greater their validity in terms of scientific evidence.

Vartanian et al.11 also observed that most of the instruments developed were primarily in English, which may hinder their international use. Simply translating the questionnaire to the language of another country does not ensure that it can be used in that country. For this, a more complex validation process is required. Only after validation can the questionnaire be administered like the original. Several research groups in Brazil have already validated the Portuguese versions of quality-of-life questionnaires to apply them with scientific validation12,13.

Until recently, quality-of-life questionnaires generally only addressed trismus.

Johnson et al.14 proposed a quality-of-life questionnaire specific for the assessment of trismus, called Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ), that was developed by the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, with only its English version validated. Currently, the GTQ is the only questionnaire specific for trismus (Figure 1). It is filled out by the patient and composed of 21 questions divided into 7 domains:

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to present and validate the Portuguese version of the GTQ to allow its effective use in Brazilian-speaking populations.

METHODS

The process of validation of the Portuguese version of the GTQ began in January 2014, with a request for authorization from the authors of the original questionnaire, and was completed in July 2015, with its application beginning in September 2014 until July 2015 as part of the validation process.

With the authorization to use and translate the instrument, the validation process was initiated in accordance with the validation procedure proposed by Guillemin et al.15-17.

The validation process was performed in four steps as follows: translation, retranslation, cultural adaptation, and revalidation:

1. Translation: performed by two native Brazilian translators in Brazil, where the instrument will be used, with the first version being completed after consensus meetings between the translators and the researchers.

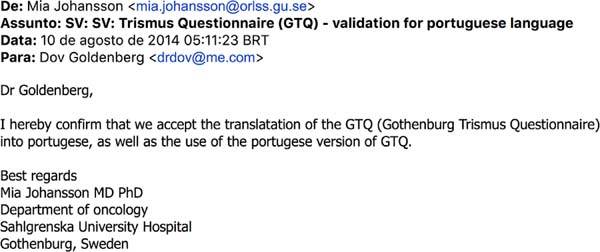

2. Back translation: translation of the preliminary Portuguese version into the source language of the questionnaire. This step was performed by two translators who had no prior knowledge of the original instrument. This version in English was analyzed in consensus meetings and sent to the original authors of the questionnaire for their analysis. To proceed with the process, the authors of the original questionnaire needed to formally agree with the back translation.

3. Cultural adaptation: administration of a preliminary version of the GTQ, with analysis of semantic equivalence (meaning of words, correct use of vocabulary, and grammar), idiomatic equivalence (use of colloquialism), and conceptual equivalence (adequacy of questions to the environment or the local situation).

4. Revalidation: evaluation of the psychometric characteristics of the instrument regarding reliability (reproducibility and internal consistency), validity (comparison of results with other studies), and responsiveness of the questionnaire. Johnson et al. also considered cost characteristics, minimum filling time (approximately 15 min), comprehension (to be self-explanatory), and possibilities of interference14.

After completing the 4 steps, the translated and validated GTQ into Portuguese (Figure 2) was administered to a population sample of 30 individuals without oral disorders to assess its effectiveness.

In each domain, the participants answered the questions, marking the most convenient answers qualitatively (e.g., answering the question on mandibular fatigue with “not at all,” “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” and “very severe”) and assigning scores to the questions so that a higher score meant worse quality-of-life regarding trismus.

For analysis of reproducibility, the internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and the reproducibility of the test-retest was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient. For the assessment of construct validity, the Pearson and Spearman correlation tests were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively18.

RESULTS

The GTQ was successfully translated and was validated and approved by the original authors (Figure 1).

The administration of the GTQ questionnaire took an average of 15 minutes in the selected sample of patients. As this is a sample of asymptomatic cases, the scores showed no trismus.

DISCUSSION

Trismus causes damage to usual activities such as eating, swallowing, talking, and performing oral hygiene, causing great discomfort to patients. It can be measured both objectively and subjectively, and the subjective measurement of quality-of-life is important to evaluate new treatment technologies.

The use of quality-of-life questionnaires enables the evaluation of the success of a given treatment, especially in patients with chronic diseases. Its translation plays an important role in promoting health knowledge to populations in different countries.

The administration of an assessment instrument validated in another language should allow comparison between different populations, countries, or cultures. Simply translating them does not ensure reliable results because it does not provide sufficient parameters to evaluate whether the results between two samples actually differ or whether they are different owing to translation errors.

Thus, all the steps proposed in the methodology here described, including back translation, must be followed.

CONCLUSION

The Portuguese version of the GTQ is a valid and reliable instrument for the evaluation of patients with limited mouth opening.

COLLABORATIONS

|

DG |

Conception and design study, final manuscript approval, project administration, validation, writing - review & editing. |

|

RN |

Final manuscript approval, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

CMA |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, data curation, investigation, realization of operations and/ or trials. |

|

LPK |

Supervision. |

REFERENCES

1. Dijkstra PU, Kalk WW, Roodenburg JL. Trismus in head and neck oncology: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2004;40(9):879-89. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.04.003

2. Bhatia KS, King AD, Paunipagar BK, Abrigo J, Vlantis AC, Leung SF, et al. MRI findings in patients with severe trismus following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(11):2586-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-009-1445-z

3. Wang CJ, Huang EY, Hsu HC, Chen HC, Fang FM, Hsiung CY. The degree and time-course assessment of radiation-induced trismus occurring after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal cancer. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(8):1458-60. PMID: 16094124 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000171019.80351.46

4. Johnson J, van As-Brooks CJ, Fagerberg-Mohlin B, Finizia C. Trismus in head and neck cancer patients in Sweden: incidence and risk factors. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16(6):CR278-82.

5. Bensadoun RJ, Riesenbeck D, Lockhart PB, Elting LS, Spijkervet FK, Brennan MT; Trismus Section, Oral Care Study Group, Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO). A systematic review of trismus induced by cancer therapies in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(8):1033-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0847-4

6. Vissink A, Jansma J, Spijkervet FK, Burlage FR, Coppes RP. Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14(3):199-212. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/154411130301400305

7. Chen WC, Hwang TZ, Wang WH, Lu CH, Chen CC, Chen CM, et al. Comparison between conventional and intensity-modulated post-operative radiotherapy for stage III and IV oral cavity cancer in terms of treatment results and toxicity. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(6):505-10. PMID: 18805047 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.07.002

8. Souza MH. Trismo após maxilectomia em tratamento de câncer de cabeça e pescoço: um estudo retrospectivo [Dissertação de mestrado]. São Paulo: Fundação Antônio Prudente; 2011.

9. Teguh DN, Levendag PC, Voet P, van der Est H, Noever I, de Kruijf W, et al. Trismus in patients with oropharyngeal cancer: relationship with dose in structures of mastication apparatus. Head Neck. 2008;30(5):622-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20760

10. Louise Kent M, Brennan MT, Noll JL, Fox PC, Burri SH, Hunter JC, et al. Radiation-induced trismus in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(3):305-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0345-5

11. Vartanian JG, Carvalho AL, Yueh B, Furia CL, Toyota J, McDowell JA, et al. Brazilian-Portuguese validation of the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2006;28(12):1115-21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20464

12. Carmo BB, Elliot LG, Leite LS, Hildenbrand L. Instrumento de Avaliação Estrangeira no Contexto da Saúde Brasileira: processo de tradução, adaptação cultural e validação. Meta Aval. 2012;4(11):120-34.

13. Mathias SD, Fifer SK, Patrick DL. Rapid translation of quality of life measures for international clinical trials: avoiding errors in the minimalist approach. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(6):403-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00435392

14. Johnson J, Carlsson S, Johansson M, Pauli N, Rydén A, Fagerberg-Mohlin B, et al. Development and validation of the Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ). Oral Oncol. 2012;48(8):730-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.02.013

15. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(12):1417-32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N

16. Guillemin F. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of health status measures. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995;24(2):61-3. PMID: 7747144 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/03009749509099285

17. Guillemin F. Measuring health status across cultures. Rheum Eur. 1995(Suppl 2):102-3.

18. Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314(7080):572. PMID: 9055718 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572

1 . Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina da

USP, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2. AC Camargo Cancer Center, São Paulo, SP,

Brazil.

3. HOSPITAL MUNICIPAL INFANTIL MENINO JESUS, SÃO

PAULO, SP, BRAZIL.

Corresponding author: Dov Goldenberg, Rua Arminda 93 cj. 121, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, Zip Code 04545-100. E-mail: dov.goldenberg@hc.fm.usp.br

Article received: May 13, 2019.

Article accepted: June 11, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter