Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

"Orthoglossopelveplasty" and the algorithm for its use in the Pierre Robin sequence

"Ortoglossopelveplastia" e o algoritmo de sua utilização na sequência de Pierre-Robin

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Several patients with the Pierre Robin sequence (micrognathia, glossoptosis, and airway obstruction) have an altered, shortened, and retractable genioglossus muscle that prevents protraction of the tongue and keeps the anterior part of the tongue vertical and its volume posteriorly displaced. This can contribute to supraglottic obstruction, feeding difficulty, and inversion of the growth stimulation forces of the mandibular body.

Methods: A retrospective study of patients with the Pierre Robin sequence treated between 2012 and 2017 with "orthoglossopelveplasty," which includes modification of glossopexy, releasing the anomalous genioglossus of its insertion and releasing the tongue to raise its anterior third and advance the volume of its base using a traction suture of the tongue base to the mandible symphysis. We present a treatment algorithm that prioritizes the need for surgery associated, or not, with mandibular distraction in accordance with respiratory and/or feeding difficulty severity.

Results: Twelve cases of oropharyngeal obstruction treated from 2012 to 2017 are presented, their priorities and orthoglossopleoplasty are discussed, and the proposed algorithm is applied.

Conclusion: Anatomical reorganization of the musculature in a correct anterior position provides protraction and functionality to the tongue, clears the airway in the oropharynx, and improves the feeding function and mandibular development, with low surgical morbidity rates and few complications.

Keywords: Glossoptosis; Pierre Robin sequence; Micrognathia; Airway obstruction; Floor of the mouth; Distraction osteogenesis

RESUMO

Introdução: Muitos pacientes portadores de sequência de Pierre Robin (micrognatia,

glossoptose e obstrução de via aérea) apresentam o músculo genioglosso

alterado, encurtado e retrátil, que impede a protração lingual, mantendo a

parte anterior da língua verticalizada e seu volume deslocado em direção

posterior. Isso pode corroborar para obstrução supraglótica, dificuldade

alimentar e inversão das forças de estímulo do crescimento do corpo

mandibular.

Métodos: Estudo retrospectivo de pacientes com Pierre Robin tratados entre 2012 e 2017

pela equipe, com descrição da "ortoglossopelveplastia", que propõe uma

modificação na glossopexia, soltando o genioglosso anômalo da sua inserção,

liberando a língua para elevar seu terço anterior e avançar o volume de sua

base, sendo auxiliada por ponto de tração da base lingual à sínfise

mandibular. Apresentamos um algoritmo de tratamento proposto que prioriza a

necessidade desta cirurgia, associada ou não à distração mandibular, de

acordo com a gravidade da dificuldade respiratória e/ou alimentar.

Resultados: São apresentados 12 casos de obstrução da orofaringe atendidos de 2012 a

2017, discutem-se suas prioridades, a ortoglossopelveplastia e se aplica o

algoritmo proposto.

Conclusão: A reorganização anatômica da musculatura em uma posição anteriorizada correta

proporciona protração e funcionalidade à língua, com desobstrução da via

aérea na orofaringe, melhora da função alimentar e do desenvolvimento

mandibular, com baixa morbidade cirúrgica e poucas complicações.

Palavras-chave: Glossoptose; Síndrome de Pierre Robin; Micrognatismo; Obstrução das vias respiratórias; Soalho bucal; Osteogênese por distração

INTRODUCTION

The treatment approach to the clinically very well-known triad of the Pierre Robin sequence, i.e., micrognathia, glossoptosis, and respiratory effort1, remains uncertain due to the wide variety of presentations of the deformity and responses to treatment.

Children with Pierre Robin sequence have upper airway obstruction and feeding difficulty2. Airway obstruction secondary to mandibular hypoplasia and glossoptosis is the major characteristic of newborns with Pierre Robin sequence, and the proposed treatments aim to avoid tracheostomy and ensure adequate feeding. The current understanding proposes non-surgical support as the first-line treatment with postural maneuvers such as prone or lateral positioning and speech-language pathology or the use of a nasopharyngeal tube. The failure of these procedures to avoid hypoxemia and hypercapnia leads to surgical procedures that include tongue-lip adhesion (glossospexy), mandibular distraction, and subperiosteal release of the floor of the mouth with or without tongue-lip adhesion3,4.

The role of mandibular hypoplasia in the genesis of this entire process remains extremely controversial, as observed in a global clinical consensus published in 2016. No direct relationship was observed between the severity of glossoptosis grade 1 on nasopharyngoscopy with that of symptoms of airway obstruction or poor nutrition, suggesting the importance of both the tongue’s retroposition and the intrinsic activity of the genioglossus coordinating its movement5.

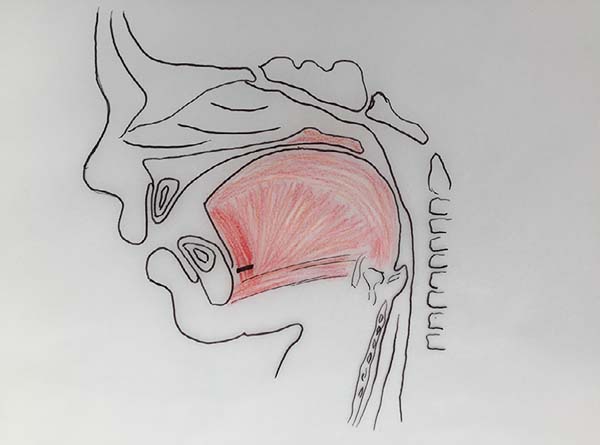

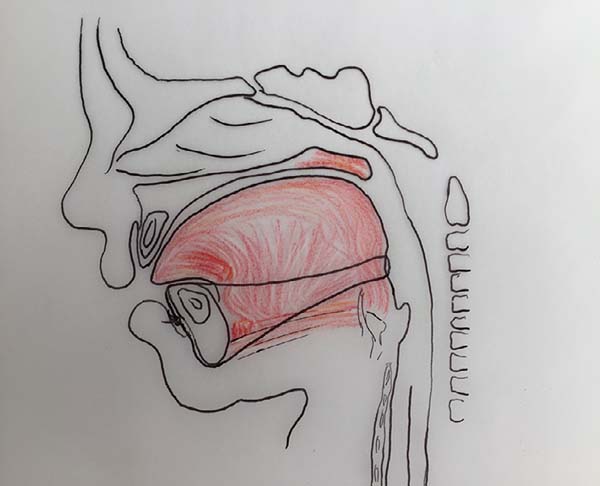

The authors, intrigued by the discrepancy between the degree of respiratory obstruction/feeding difficulty and that of mandibular retrognathism, turned their attention to an alteration eventually found in the positioning of the genioglossus muscle and observed its shortening and firm adherence to the mandibular symphysis, preventing lingual protraction and possibly causing lingual rotation and posterior supraglottic obstruction6 (Figure 1, altered tongue position with resulting glossoptosis).

Based on the history of various techniques previously used and anatomical changes found in the lingual musculature, correction of this musculature alteration is proposed in this study. The correction technique of this ankyloglossia is described as a proposed modification of glossospexy to “orthoglossopelveplasty.” Here, we describe the evolution of the operated cases.

OBJECTIVE

Here we describe orthoglossopelveplasty, propose a modification of glossospexy to correct the ankyloglossia of patients with the Pierre Robin sequence, and analyze the evolution of operative cases according to the proposed treatment algorithm.

METHODS

This study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients with glossoptosis treated by the Plastic and Craniofacial Surgery team of Advanced Plastic Surgery Center of Beneficência Portuguesa Hospital in São Paulo, SP, Brazil, with the proposed orthoglossopelveplasty technique and respective evolutions from May 2012 to August 2017 were analyzed in this study.

The 12 patients included in this study had the Pierre Robin sequence at birth and were initially treated conservatively with lateral/ventral decubitus postural maneuvers, nasopharyngeal cannula, and speech therapy. According to subsequent evaluations of the difficulty of lingual protrusion, feeding difficulty, and degree of upper airway obstruction due to glossoptosis, they were classified by criteria that enabled an algorithm of proposed approaches.

- Grade 1: Efficient breathing and food intake in the lateral/ventral decubitus => observation, maintenance of conservative treatment, and speech support

- Grade 2: Efficient breathing in lateral/ventral decubitus - inefficient food intake (need for probe) => treatment with orthoglossopelveplasty

- Grade 3: Inefficient breathing in lateral/ventral decubitus, efficient food intake => treatment with osteogenic distraction of the jaw

- Grade 4: Inefficient breathing and food intake in lateral/ventral decubitus => treatment with osteogenic distraction and orthoglossopelveplasty

The surgical indication for muscular and functional reorganization of the tongue by orthoglossopelveplasty was revealed using physical examinations and speech therapy demonstrating a change in the lingual cannulation of affected children, with posteriorization and elevation of the tongue in an antagonic movement during suctioning and swallowing, corroborated intraoperatively with difficulty of lingual exteriorization under traction. The association of orthoglossopelveplasty with mandibular distraction was observed in patients who maintained inefficient breathing with postural maneuvers and speech therapy according to the proposed algorithm.

The results were analyzed with regard to the evolution of patients treated according to morbidity and mortality data and the need for tracheostomy and/or gastrostomy.

Description of the technique

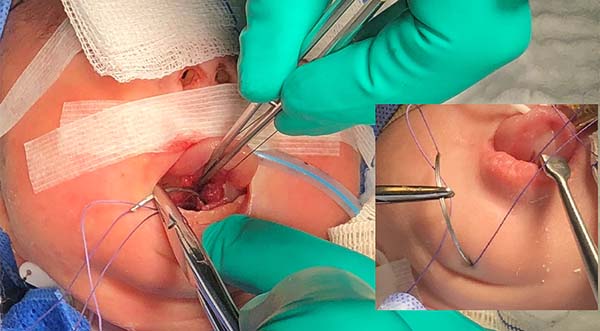

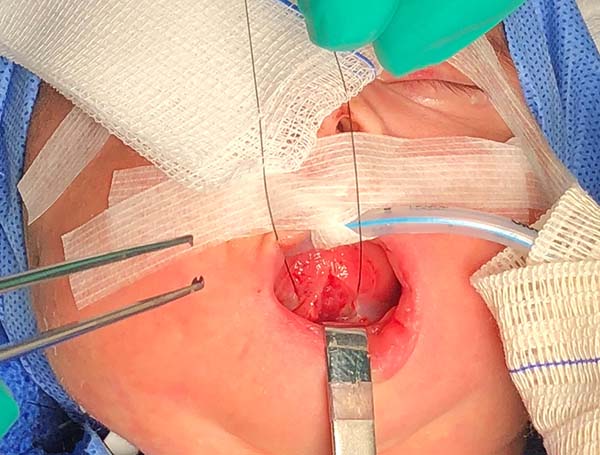

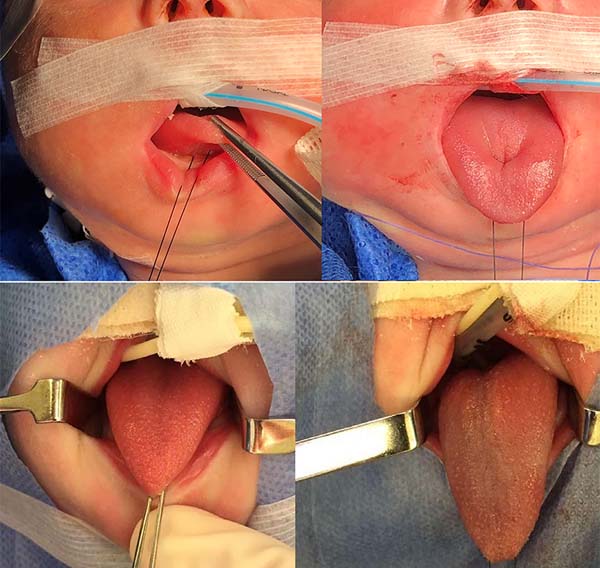

The proposed orthoglossopelveplasty technique, used to appropriately reposition the tongue while addressing the floor of the mouth, is illustrated below (Figures 2 and 3):

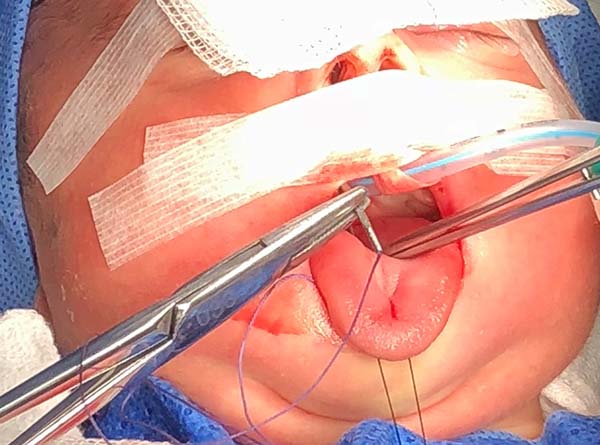

1. Pass a nylon 3.0 suture in the distal third of the tongue to accomplish traction (Figure 4).

2. Perform median vertical incision on the ventral lingual mucosa; this may be a Z as a zetaplasty in cases of a short lingual frenulum (Figure 4).

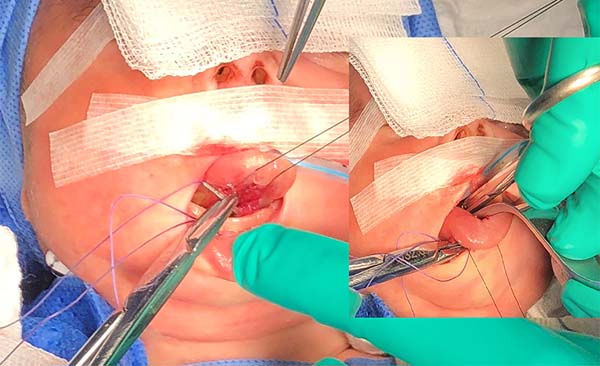

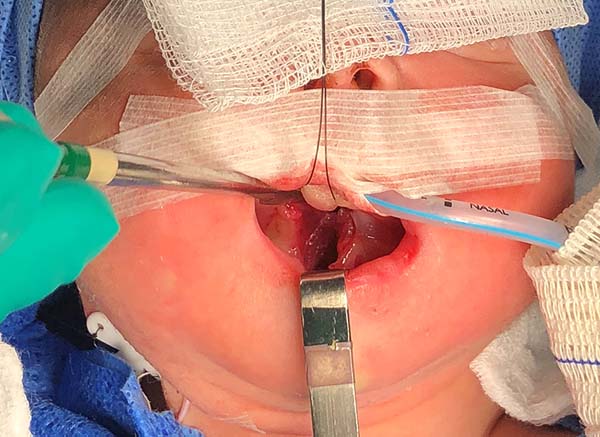

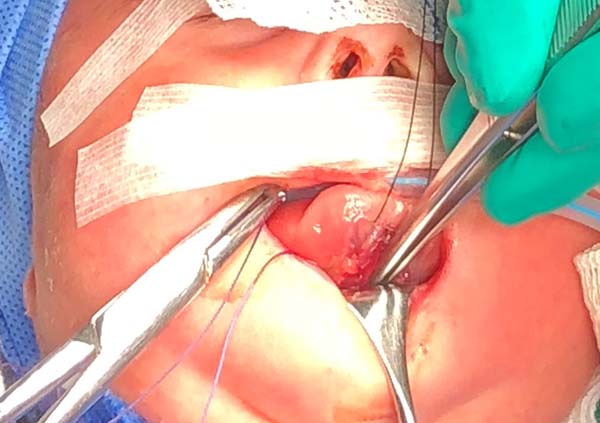

3. Access the median muscles of the floor of the tongue, especially the shortened genioglossus, detach it from its insertion in the mandibular symphysis and release its fibers retracted using Metzenbaum scissors, and bluntly dissect the intermuscular sagittal line to the tongue base (Figure 5).

4. Test the release of the tongue by pulling it with the nylon suture used earlier and note its correct protraction; in the absence of effective protraction, the muscle should be released.

5. Anteriorly reposition the tongue base with a transfixing point of absorbable polyglactin 2.0 with a 3.0-cm needle to anchor the mandibular symphysis by cerclage.

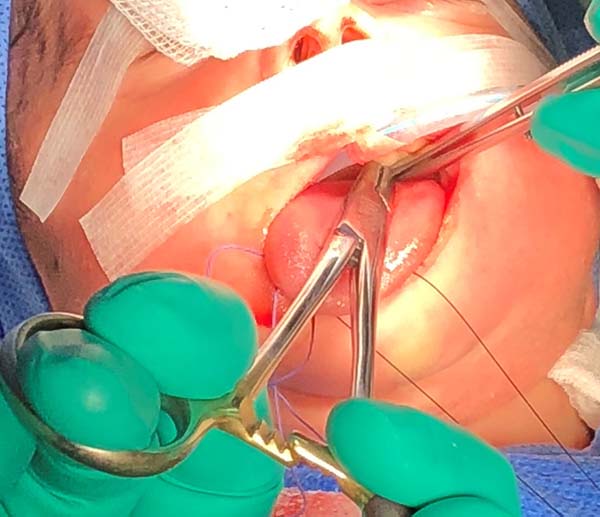

- The suture starts centrally in the gingivolabial groove, passes through the anterior aspect of the mandibular symphysis until it exits the skin of the submentum, and returns through the same orifice, accompanying the mandibular lingual face to the vestibular mucosa of the base of the tongue, preparing the cerclage of the mandibular symphysis (Figure 6).

- The needle follows in the posterior direction by the base of the tongue until passing below the lingual V (Figures 7 and 8) and returns by the same level of the tongue base up to the vestibule and on the mandible until the gengivolabial groove, where the final knot is made (Figures 9 and 10).

At the end of orthoglossopelveplasty, improved tongue protraction and positioning are evident (Figure 11).

RESULTS

After attempted conservative treatment in the first days of life, in 12 patients, orthoglossopelveplasty was performed, with 4 treated with this technique alone and 8 treated with osteogenic distraction of the jaw.

Results evaluated (Chart 1).

| 3 cases | 2 cases | Grade 4 moderate respiratory obstruction and feeding difficulty | Osteogenic distraction of the mandible and Orthoglossopelveplasty | Evolved without need for tracheostomy and gastrostomy |

| Evolution without tracheostomy or gastrostomy | 1 case | Grade 2 without respiratory difficulty with difficulty in food intake | Orthoglossopelveplasty | Evolved without need for gastrostomy |

| 2 cases | 1 case | Grade 3 respiratory difficulty without feeding difficulty | Osteogenic distraction of the jaw | Tracheostomy maintained due to respiratory difficulty induced by laryngomalacia |

| Evolution without Postoperative Tracheostomy | 1 case | Grade 4 respiratory obstruction and food difficulty | Distração osteogênica de mandíbula e Orthoglossopelveplasty | Maintained tracheostomy due to persistent respiratory difficulty because of tracheal stenosis |

| 1 case | 1 case | Grade 4 respiratory obstruction and feeding difficulty | Osteogenic distraction of the jaw, Orthoglossopelveplasty | Edwards syndrome and intense diffuse hypotonia; it was possible to withdraw the tracheostomy but not the gastrostomy; |

| Evolution without Postoperative Gastrostomy | ||||

| 2 cases | 1 case | Grade 3 Difficulty in food intake and respiratory obstruction | Osteogenic distraction of mandible and ortoglossopelviplasty, but evolved with gastrostomy and tracheostomy due to laryngomalacia | It evolved with the removal of the tracheostomy and gastrostomy with ortoglossopelveplastia and evolution of distraction jaw and surgical correction of laryngomalacia; |

| Evolution without tracheostomy and postoperative gastrostomy | 1 case | Grade 4 respiratory obstruction and food difficulty | Osteogenic distraction of the mandible and Orthoglossopelveplasty | Needed tracheotomy for laryngomalacia |

Four patients arrived at the service with a history of previous tracheostomy and gastrostomy performed by other teams; thus, they required orthoglossopleoplasty and osteogenic distraction of the jaw (Chart 2).

| Previous tracheostomy and gastrostomy; osteogenic (n = 4) | Distraction of the jaw and orthoglossopleoplasty | 1 case | Withdraw tracheostomy | Withdraw gastrostomy |

| 1 case | Programmed withdrawal of tracheostomy | Gastrostomy could not be removed due to severe chalasia of the esophagus | ||

| 1 case | Tracheostomy impossible due to tracheomalacia | Withdraw gastrostomy | ||

| 1 case | Died during heart surgery | Died during heart surgery |

Morbidity: One case of infection of the operative wound in the suture passage on the submentum treated with first-generation cephalosporin.

Mortality rate in the intraoperative or immediate postoperative period and recent demonstrating failure of the procedure: None.

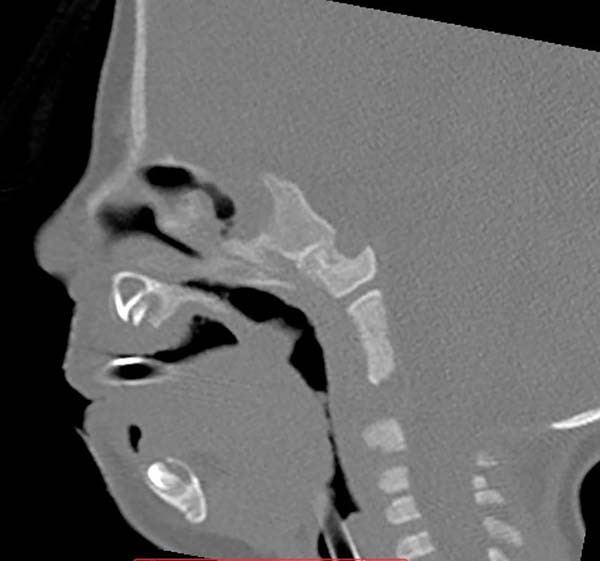

Images show the effects of orthoglossopelveplasty on supraglottis obstruction (Figure 12) and the evolution of a patient with Pierre Robin sequence and feeding difficulty treated with orthoglossopelveplasty alone, demonstrating posterior mandibular growth due to the correction of its growth forces (Figure 13).

DISCUSSION

Glossoptosis, together with retrognathism, can cause feeding difficulty and type 1 and 2 upper airway obstruction (more frequent and severe in the immediate postnatal and neonatal periods) that can be treated initially by postural maneuvers and nasopharyngeal intubation7. Surgical interventions in micrognathia are considered when adequate clinical management fails8. The majority of authors perform glossopexy as the initial treatment in cases of Pierre Robin that did not improve with clinical management; if there are continuous desaturations with respiratory difficulty in the prone position after glossopexy, osteogenic distraction of the mandible is usually performed; if the difficulty remains, tracheostomy is an option9,10.

The initial glossopexy described by Douglas (tension suture passed from the dorsum of the tongue through the lower lip to the chin, where it is tied on a silicone button) presented numerous complications, including tongue lacerations, wound infection, dehiscence, damage to the Wharton’s ducts, scar ankyloglossia, and deforming scars of the lip, chin, and floor of the mouth.

Currently, the modified procedure with tongue-lip adhesion6 (genioglossus detached from the mandible and tied to it by two absorbable sutures passing through two mandibular perforations associated with the suture of the muscle and mucosa of the anterior lingual border and lip) is more commonly used due to the lower functional or aesthetic deficit but features poor position of the mandibular deciduous teeth, a high dehiscence rate, feeding problems, and poor dental hygiene and often results in the early release of glossospexy at 6-9 months prior to palatoplasty and occasionally requiring additional surgeries6,11.

A new approach was initiated after perception of the constriction of the muscle insertion of the tongue in the jaw by dystopia of the genioglossus insertion. This constriction would be responsible for the elevation of the tip of the tongue, glossoptosis, and respiratory obstruction seen in the Pierre Robin sequence in addition to being a causal factor of micrognathia. The release of the genioglossus from the mandible could theoretically allow the tip of the tongue to move forward to a normal position.

Since then, studies have shown that subperiosteal release from the floor of the mouth could be an effective way of clearing of the airways in patients with Pierre Robin sequence11 as it would release the musculature of the floor of the mouth under increased tension pulling the tongue upward and rearward12,13. This technique consists of a submental incision; incision of the periosteum lingual and detachment of the mandible; and release of the origin of the genioglossus, genio-hyoid, and milo-hyoid and the rest of the muscles of the floor of the mouth from the edge of the mandible up to the angle of the mandible, allowing the most anterior positioning of the tongue. In the postoperative period, patients are kept intubated for 1 week for weight and height gain, to reduce the swelling of the floor of the mouth, and to support the tongue-forward position12.

This intervention would be effective for treating moderate micrognathia; more severe cases might require osteogenic distraction14. This would be advantageous on classical glossospexy by treating the possible etiology of micrognathia and does not result in as many dehiscence issues and reoperations and injuries to structures such as the Wharton’s ducts.

Other authors have emphasized the importance of the abnormal origin of the genioglossus muscle6,15. Argamaso6 reported that he found resistance to tongue protraction by an abnormally shortened genioglossus muscle firmly attached to the symphysis of the mandible, recommending a subperiosteal separation of this muscle as part of the glossospexy procedure. It is even possible that, by releasing the genioglossus of the mandible, we “unblock the restriction of growth in the mandible” and have normal mandibular development as recent studies have shown that most patients with Pierre Robin sequence do not attain the same normal cephalometric level even after accelerated compensatory growth16.

Thus, based on the concept of genioglossus shortening, we introduce a technical modification of glossopexy and the release of this muscle. Using orthoglossopelveplasty, we release the short lingual frenulum (when necessary); after the genioglossus muscle is shortened from its tense and abnormal insertion in the mandibular symphysis, it may have a more normal insertion anatomy. After that, we performed glossopexy, pulling the tongue anteriorly from its base up to the submentum.

Thus, our proposed orthoglossopelveplasty technique is also directed to the pathological process of the abnormal contraction of the muscles of the floor of the tongue. Using it, we seek less surgical extension and possible complications, an absence of damage to dental hygiene, and the consequent need for early withdrawal of the pexy suture.

Using orthoglossopelveplasty, we eliminate the resistance to protraction of the tongue generated by the tense, short, and fixed genioglossus muscle, possibly causing micrognathia due to tension of the tongue upward and rearward and the glossoptosis. We also allow anatomical reorganization of the musculature in an anterior position, occupying the area where the anterior part of the tongue was previously imprisoned and generating its paradoxical movements during suction.

Tongue-lip adhesion remains the surgical procedure of choice in patients with Pierre Robin sequence for many surgeons in the United States according to a study in 201417; it is also used in many other countries. Identifying the presence of persistent and significant airway obstruction is important for those who continue to use this procedure because the treatment has the potential to prevent long-term consequences of airway obstruction and risk factors for persistent post-glossopexy airway obstruction could be identified to establish better criteria for surgical intervention type3.

It is worth mentioning that classical glossospexy reinforces the effect of the already shortened genioglossus, provoking even greater mobilization of the lingual volume against the oropharynx.

This perception of different levels of the severity of symptoms of respiratory obstruction and feeding difficulty and consequently different developments and the need for treatment of our patients with Pierre Robin sequence led us to enlarge the Caouette-Laberge18, classification of the severity of symptoms and propose the classification used.

Our results suggested that orthoglossopelveplasty is effective, functional, and anatomical, featuring lower surgical extension and fewer complications. Looking at the developments, we observed that orthoglossopelveplasty was successful in cases in which feeding difficulty was predominant; we also observed the possibility of postoperative mandibular growth. It also presented as an adjuvant technique for improving respiratory difficulty and the osteogenic distraction of the mandible in micrognathia.

Thus, the best treatment for cases of moderate respiratory difficulty in prone decubitus and feeding difficulty was possible, allowing for the prevention of tracheostomy and gastrostomy. More severe cases of respiratory and feeding difficulty required tracheostomy, and subsequent investigations pointed out additional pathologies in the lower airways that are more frequent in syndromic Pierre Robin cases.

Even in severe cases, orthoglossopelveplasty associated with osteogenic distraction of the mandible allowed for the removal of the tracheostomy and gastrostomy in several cases, leading to better a quality of life of patients and decreased medical and hospital expenses. Cases in which this withdrawal was not possible had other more severe causes of breathing and feeding difficulties such as tracheomalacia, esophageal achalasia, and severe syndromes with body hypotonia that were usually associated with syndromic Pierre Robin sequence.

CONCLUSION

Orthoglossopelveplasty allowed the treatment of airway obstruction caused by poor tongue positioning, improving the feeding function and mandibular development, with low surgical morbidity rates and few complications.

COLLABORATIONS

|

VLNC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, conceptualization, final manuscript approval, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing - review & editing. |

|

JHP |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, realization of operations and/ or trials, visualization, writing - original draft preparation. |

|

ASS |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, validation, writing - review & editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Robin P. Glossoptosis due to atresia and hypotrophy of the mandible. Am J Dis Child. 1934;48:541-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1934.01960160063005

2. Evans KN, Sie KC, Hopper RA, Glass RP, Hing AV, Cunningham ML. Robin sequence: from diagnosis to development of an effective management plan. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):936-48. PMID: 21464188 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2615

3. Almajed A, Viezel-Mathieu A, Gilardino MS, Flores RL, Tholpady SS, Côté A. Outcome Following Surgical Interventions for Micrognathia in Infants With Pierre Robin Sequence: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2017;54(1):32-42. PMID: 27414091 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1597/15-282

4. Denny A, Amm C. New technique for airway correction in neonates with severe Pierre Robin sequence. J Pediatr. 2005;147(1):97-101. PMID: 16027704 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.02.018

5. Sher AE, Shprintzen RJ, Thorpy MJ. Endoscopic observations of obstructive sleep apnea in children with anomalous upper airways: predictive and therapeutic value. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1986;11(2):135-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-5876(86)80008-8

6. Argamaso RV. Glossopexy for upper airway obstruction in Robin sequence. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1992;29(3):232-8. PMID: 1591256 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1597/1545-1569_1992_029_0232_gfuaoi_2.3.co_2

7. Marques IL, de Sousa TV, Carneiro AF, Barbieri MA, Bettiol H, Gutierrez MR. Clinical experience with infants with Robin sequence: a prospective study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2001;38(2):171-8. PMID: 11294545 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1597/1545-1569_2001_038_0171_cewiwr_2.0.co_2

8. Caouette-Laberge L, Plamondon C, Larocque Y. Subperiosteal release of the floor of the mouth in Pierre Robin sequence: experience with 12 cases. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1996;33(6):468-72. PMID: 8939370 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1597/1545-1569_1996_033_0468_srotfo_2.3.co_2

9. Schaefer RB, Stadler JA 3rd, Gosain AK. To distract or not to distract: an algorithm for airway management in isolated Pierre Robin sequence. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(4):1113-25. PMID: 15083010

10. Kirschner RE, Low DW, Randall P, Bartlett SP, McDonald-McGinn DM, Schultz PJ, et al. Surgical airway management in Pierre Robin sequence: is there a role for tongue-lip adhesion? Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2003;40(1):13-8.

11. Butow KW, Hoogendijk CF, Zwahlen RA. Pierre Robin sequence: appearances and 25 years of experience with an innovative treatment protocol. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(11):2112-8. PMID: 19944218

12. Delorme RP, Larocque Y, Caouette-Laberge L. Innovative surgical approach for the Pierre Robin anomalad: subperiosteal release of the floor of the mouth musculature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83(6):960-4.

13. Siddique S, Haupert M, Rozelle A. Subperiosteal release of the floor of the mouth musculature in two cases of Pierre Robin sequence. Ear Nose Throat J. 2000;79(10):816-9. PMID: 11055103

14. Breugem CC, Olesen PR, Fitzpatrick DG, Courtemanche DJ. Subperiosteal release of the floor of the mouth in airway management in Pierre Robin sequence. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(3):609-15.

15. Shprintzen RJ. The implications of the diagnosis of Robin sequence. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1992;29(3):205-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0952398920290315

16. Eriksen J, Hermann NV, Darvann TA, Kreiborg S. Early postnatal development of the mandible in children with isolated cleft palate and children with nonsyndromic Robin sequence. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43(2):160-7. PMID: 16526921

17. Scott AR, Mader NS. Regional variations in the presentation and surgical management of Pierre Robin sequence. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(12):2818-25.

18. Caouette-Laberge L, Bayet B, Larocque Y. The Pierre Robin sequence: review of 125 cases and evolution of treatment modalities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(5):934-42.

1. Hospital Beneficiência Portuguesa de São

Paulo, Núcleo de Cirurgia Plástica Avançada, São Paulo, SP,

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Vera Lúcia Nocchi Cardim, Rua Augusta, 2705, 4º andar - sala 42, Cerqueira César, SP, Brazil, Zip Code 01413-100. E-mail: vera@npa.med.br

Article received: June 13, 2018.

Article accepted: April 21, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter