Special Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Severe complication due to inappropriate use of polymethylmethacrylate: a case report and current status in Brazil

Complicação grave do uso irregular do PMMA: relato de caso e a situação brasileira atual

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Use of permanent fillers can lead to significant complications. In Brazil, polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) is a product approved by the Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA), but its use exceeds its indications, leading to serious complications. Recommendations for restricted use have been in place for more than a decade, but cases with serious consequences due to inappropriate use are still seen.

Objective: To report a serious complication due to inappropriate use of PMMA and discuss the current status of PMMA use in Brazil based on recommendations of medical societies and regulatory agencies.

Methods: This report describes a case of extensive necrosis of the gluteal region after injection of PMMA by a non-qualified practitioner; the report also reviews the literature on the current status of PMMA use in Brazil.

Discussion: Despite the efforts of medical societies, acute and chronic complications are still reported in the Brazilian literature. In 2016, more than 17,000 PMMArelated complications were reported; nevertheless, reliable epidemiological data remain unavailable because the number of treatments, the quality of the product, and the training of practitioners remain unregulated.

Conclusion: A significant number of repair procedures are performed in Brazil to correct complications resulting from the use of PMMA. The severity of the reported case highlights the need to combat bad practice by untrained professionals, as well as the need for greater control of PMMA marketing by regulatory agencies.

Keywords: Polymethylmethacrylate; Skin fillers; Brazil; National Health Surveillance Agency; Health advice; Reconstructive surgical procedures/adverse effects

RESUMO

Introdução: Os preenchedores permanentes, apesar de resultados duradouros, são verdadeiros problemas quando causam complicações. No Brasil, o PMMA é um produto aprovado pela Anvisa, mas seu uso extrapola suas indicações, levando a complicações graves. Há mais de uma década, existem recomendações sobre sua restrição, mas casos com consequências graves do seu uso irresponsável são atuais.

Objetivo: Relatar complicação grave do uso irregular do PMMA e discutir a realidade brasileira atual baseado em determinações das entidades médicas, assim como dos órgãos reguladores.

Métodos: É relatado um caso de necrose extensa da região glútea após a injeção de PMMA por profissional não qualificado e discutida a situação brasileira atual do produto com base nas entidades médicas e revisão da literatura do Brasil.

Discussão: Apesar do esforço das entidades médicas, são inúmeros os casos de complicações agudas e crônicas relatados na literatura brasileira. No ano de 2016, foram registradas mais de 17 mil complicações relacionadas ao PMMA, mesmo assim, é difícil estabelecer dados epidemiológicos confiáveis, pois não há controle do número de aplicações, da qualidade do produto utilizado e da capacitação dos profissionais que o utilizam.

Conclusão: No Brasil, há um número expressivo de procedimentos reparadores para correção de complicações decorrentes do uso do PMMA. A gravidade do caso relatado traz à tona a necessidade de combate à má prática por profissionais não capacitados, assim como um controle mais rigoroso da comercialização do produto por entidades reguladoras.

Palavras-chave: Polimetil metacrilato; Preenchedores dérmicos; Brasil; Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária; Conselhos de saúde; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos/efeitos adversos

INTRODUCTION

Fillers used in aesthetic medicine can be divided into 2 major groups: absorbable fillers and permanent fillers1. Some of the advantages of absorbable fillers include the reversibility of undesired results, whether by action of an “antidote” or through resorption by the body itself. With permanent fillers, however, complications become a real problem due to persistence of the product and perpetuation of unwanted results2.

These complications are inherent to all types of fillers and may be classified as acute or chronic. Acute complications include vascular embolism, necrosis, allergic reactions, and infections. Chronic complications include granuloma formation, deformities, and inflammatory reactions2.

The acute complications deserve attention because they depend directly on practitioner qualifications and training. For the most part, this type of complication is more related to treatment technique and not necessarily to the product used3.

The most commonly used permanent filler is polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). PMMA is available as polymeric microspheres ranging in size from 30 to 103 µm. These spheres are suspended in a vehicle of bovine collagen, carboxymethylcellulose, or sodium hyaluronate, which are resorbed after a few days2.

In 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administrationapproved ArteFill for use by physicians alone, and limited its application to perioral volume augmentation, e.g., nasolabial filling, excluding that of the lips4. In Brazil, the National Health Surveillance Agency (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, ANVISA) recommends use by trained medical professionals, and does not contraindicate use for body filling or provide guidelines for aesthetic use5.

As PMMA is inexpensive and easily obtained, numerous cases of complications have occurred, arising from use by untrained professionals in substandard aesthetic centers. This case report describes complications due to use of PMMA filler in a clandestine clinic in the city of São Paulo, and discusses the current status of PMMA use in Brazil.

CASE REPORT

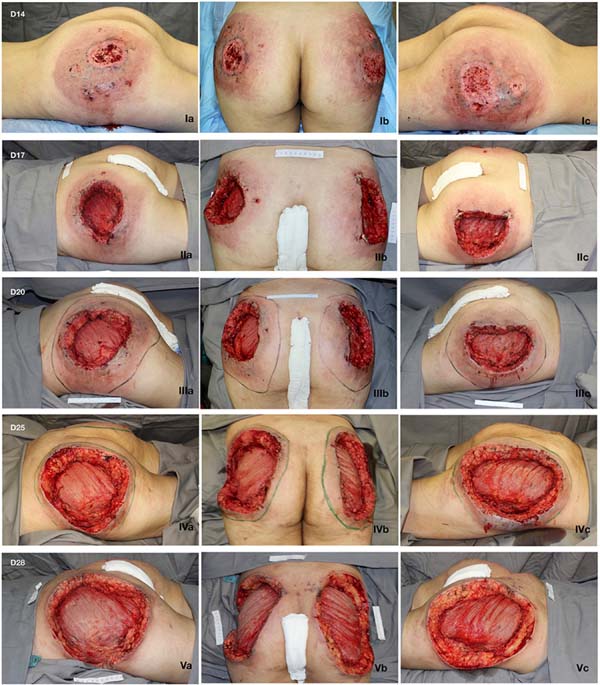

A 21-year-old female presented with a history of injection of 900 ml of PMMA in the buttocks 12 days prior. The procedure was performed in a beauty salon by a nonmedical professional. She had pain and ulcerated wounds with purulent secretions at the injection site (Figure 1), and had already received ciprofloxacin and clindamycin for 7 days without improvement, as well as day hospital treatment with ceftriaxone and prednisone.

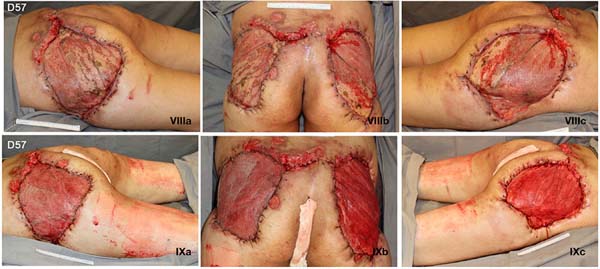

On admission, the patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis and elevated C-reactive protein, and computed tomography showed densification and thickening of the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the gluteal regions, in addition to multiple nodular formations consistent with exogenous material/granulomas (Figure 2), but no evidence of collections.

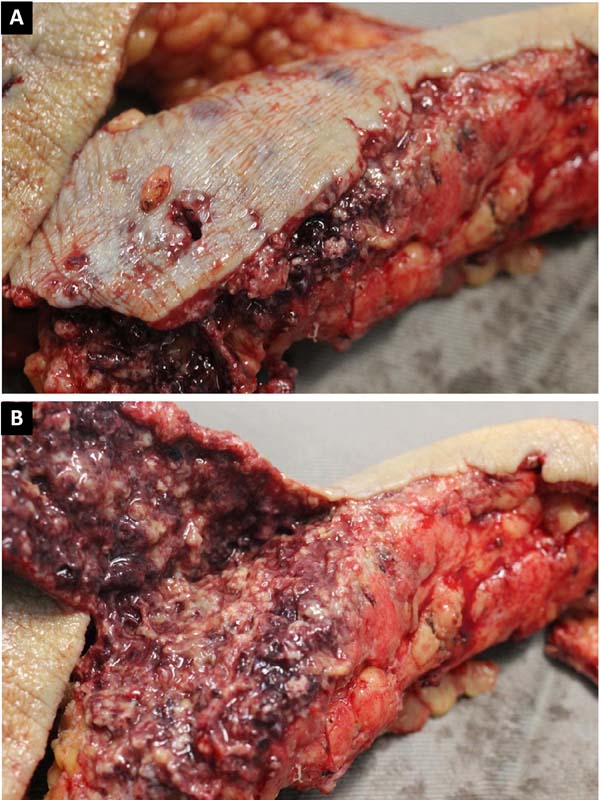

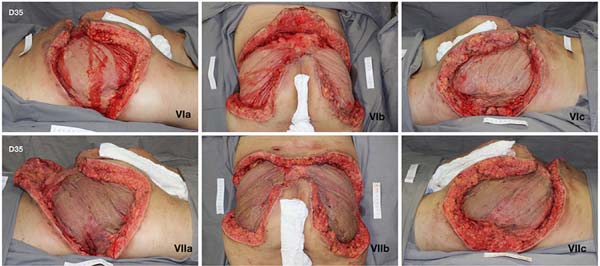

She initially received empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, but the wound deteriorated. Serial debridement was performed (Figure 1), and continuous negative pressure therapy was applied at 125 mmHg, with sequential exchanges every 3 to 5 days. Suppuration and necrosis of the dermis (Figure 3) and subcutaneous tissue were observed, with nodular formations containing pus and exogenous material in addition to signs of bilateral gluteus maximus fasciitis. Fragments of soft tissue were sent for culture, but no microorganism was identified.

Due to the severity of the inflammatory/infectious process, she remained in the intensive care unit for 14 days, and developed acute renal failure. She showed progressive improvement after the 3rd debridement.

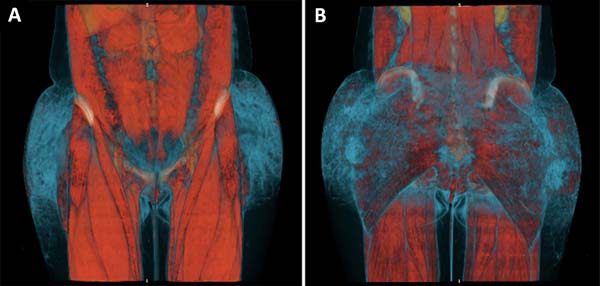

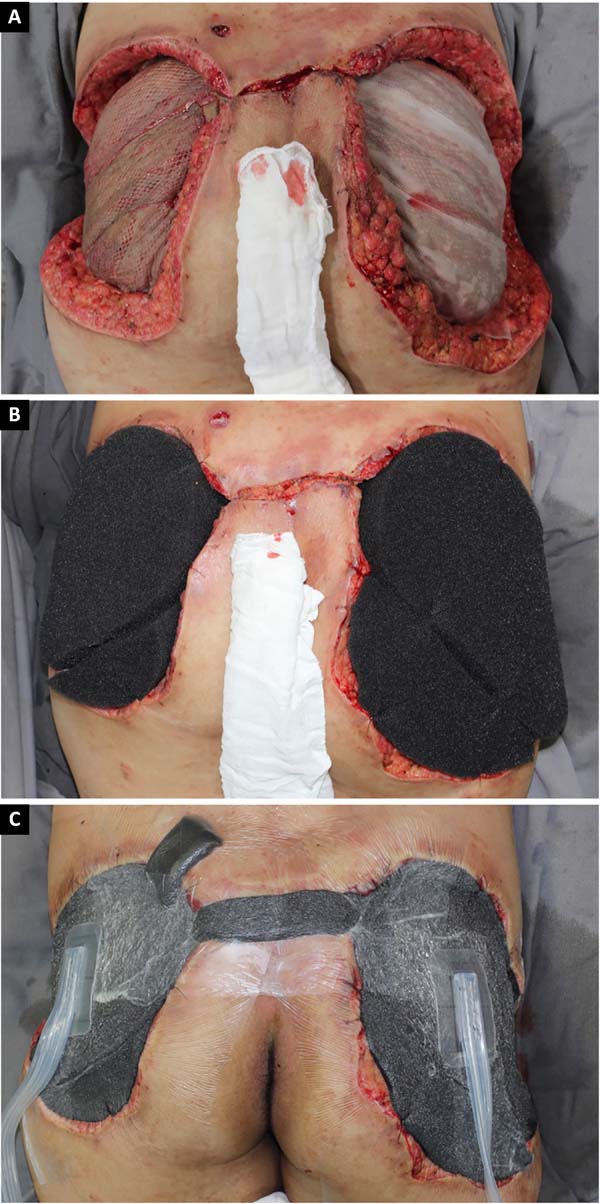

Given the size of the wound after sequential debridement and the extensive loss of nutrients, hemoglobin, and microelements, bilateral homologous skin grafting was performed over the gluteus maximus (Figure 4), with addition of negative pressure therapy (Figure 5).

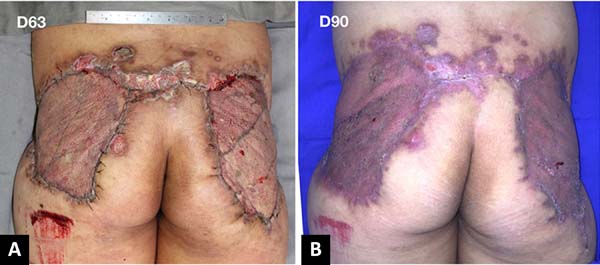

After 3 weeks of treatment with biological dressings (homologous grafts) and improvement of nutritional parameters, autologous skin grafting was performed (Figure 6) with 1:1.5 mesh. The graft showed good integration (Figure 7) without functional deficits, and the patient was discharged after 68 days of hospitalization.

PMMA in Brazil

The use of PMMA as a filler has been approved under federal law since 2004 for treatment of HIV-associated lipodystrophy6. However, indiscriminate use for aesthetic purposes without scientific evidence merited a public alert by the Federal Medical Council (Conselho Federal de Medicina, CFM) in 2006, as non-qualified practitioners promoted a technique known as “bioplasty”.7

In 2007, ANVISA prohibited the preparation of PMMA products by compounding pharmacies in order to regulate quality and purity8.

In 2008, complications related to PMMA use in a series of 32 cases led to classification into 5 types: necrosis, granuloma, chronic inflammatory reaction, lip complications, and infection. Necrosis is always an acute complication, whereas inflammatory complications can occur many years after injection. The rarity of the complications was highlighted, but it was difficult to estimate the incidence and prevalence in the entire population. In addition, concern was raised about serious complications, which, in addition to being permanent, are often untreatable2.

In 2009, another series of 18 cases with various complications related to PMMA use highlighted the indiscriminate use of this substance owing to its low cost and the lack of regulation of its sale to nonspecialist physicians and nonphysicians9. In 2012, a histopathological study of 63 cases of complications attributed to PMMA identified 5 cases with acute complications, all of which developed necrosis after injection10.

In 2010, the Regional Medical Council of Paraná (Conselho Regional de Medicina do Paraná, CRM-PR) issued an opinion that the unrestricted use of PMMA in gluteal augmentation, or use in large quantities, was unsafe and unpredictable, and could lead to chronic reactions and unmanageable complications11. In 2012, ANVISA issued a safety alert highlighting the possible chronic complications of PMMA, as well as the need for professional training in its use12,13.

In 2013, the CFM issued a new opinion reinforcing the 2010 opinion of the CRM-PR and reaffirming the limited indications for PMMA injection, noting that use in large quantities could lead to unpredictable results14. In this opinion, both the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, SBCP) and the Technical Chamber of Plastic Surgery of the CFM recommended that PMMA only be used by physicians, as well as in small doses and with restrictions.

The 2016 census by the SBCP-SP (regional São Paulo branch) reported that a total of 4,432 procedures were performed to treat complications of PMMA injection, equivalent to 0.7% of the total number of reparative procedures in that year15. In the same year, more than 17,000 complications associated with use of PMMA were recorded in Brazil. Meanwhile, the use of nonsurgical procedures (primarily for filling) increased by 390% in a 2-year period16.

DISCUSSION

Based on the data for the last decade, concerns about these procedures are inevitable. Despite the significant and immediate results in aesthetic filling, the unregulated popularization of PMMA use, in addition to its use in large volumes with inadequate technique, have shown that PMMA can be harmful when misused for this purpose.

In Brazil, the regulation and supervision of aesthetic medical centers by responsible agencies remain inadequate. In addition, despite the efforts of medical societies, misinformation is widely disseminated, made worse by increasing exposure on social media. This misinformation exposes patients to unsafe procedures.

With reports of significant adverse outcomes in the Brazilian media in recent years, including mutilating and fatal cases, medical societies have spoken out against the use of PMMA for aesthetic purposes. In 2018, both the SBCP and the Brazilian Society of Dermatology (Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia, SBD) issued a warning on the use of PMMA, with a contraindication for use in large amounts, reinforcing the unpredictability of results and requesting the recategorization and restriction of its use by ANVISA17.

Reports of adverse outcomes related to PMMA are rare in the medical literature, with complication rates ranging from 0.01% to 3%2,18. Although small, these numbers deserve attention, since underreporting of complications is known to occur, both because they may be delayed and also due to omission of reporting in the medical record3. Furthermore, it may be unclear whether complications are caused by PMMA itself or poor technique. Complications caused by permanent fillers deserve special attention, because they create chronic problems and are difficult to treat. Despite the availability of protocols, there is no consensus on standardization of treatment19.

Complications, such as necrosis, are even rarer (0.003%)18. Technical failure is attributed to the application of needles in flat surfaces and not necessarily to PMMA. In one author’s account of personal experience with more than 5,000 cases published in 201220, a complication rate of 0.01% was reported, with no necrosis observed. This was ascribed to adherence to 3 principles: deep plane application, use of a microcannula, and use of pure and certified PMMA.

In the case described herein, both the quality of the product and the technique used were questionable. The combination led to severe complications.

Acute local inflammation within the first hours after treatment was an important warning sign that required close monitoring. With progression to necrosis, aggressive surgical debridement combined with negative pressure therapy were imperative for treatment of inflammation and preparation of the wound bed21. Debridement surgery is challenging, because healthy tissue is invaded by necrotic tissue, creating a false impression of satisfactory treatment. Coverage of the wound after proper cleaning is also challenging, however, and sequelae and deformities may not be be fully corrected by plastic surgery.

The use of diagnostic tomography in the present case was a predictor of the extent of necrosis, since it revealed densification of affected tissue, even in areas that still appeared clinically healthy. The findings coincided with the debrided areas. There are no comparable studies in the literature.

CONCLUSION

Despite low published complication rates in Brazil, an excessive number of repair procedures are needed to correct complications from use of PMMA. The severity of the reported case highlights the need to combat bad practice by untrained practitioners, as well as the need for greater regulation of the commercialization of PMMA. Complications can lead to death and permanent deformity, and treatment is challenging.

COLLABORATIONS

|

KTK |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, data curation, final manuscript approval, investigation, methodology, project administration, realization of operations and/or trials, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

MM |

Realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

DAM |

Realization of operations and/or trials, supervision, writing - review & editing. |

|

AAMJ |

Supervision. |

|

RG |

Supervision, visualization. |

REFERENCES

1. Carruthers J, Carruthers A, Humphrey S. Introduction to Fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):120S-31S.

2. Salles AG, Lotierzo PH, Gemperli R, Besteiro JM, Ishida LC, Gimenez RP, et al. Complications after polymethylmethacrylate injections: report of 32 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(5):1811-20. PMID: 18454007 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31816b1385

3. Rzany B, DeLorenzi C. Understanding, Avoiding, and Managing Severe Filler Complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):196S-203S.

4. U. S. Food and Drug Administration - FDA. ArteFill® - P020012. Silver Spring: FDA; 2006 [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P020012

5. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Agência de Vigilância Sanitária (Anvisa). Anvisa esclarece sobre indicações do PMMA. Brasília: Anvisa; 2018 [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/rss/-/asset_publisher/Zk4q6UQCj9Pn/content/anvisa-esclarece-sobre-indicacoes-do-pmma/219201?inheritRedirect=false

6. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Portaria Conjunta SAS SVS Nº 01, de 20 janeiro de 2009. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2009 [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/33868/2492231/doc_alerta_954.pdf

7. Jornal da Associação Médica. Especialidade: CFM faz alerta sobre bioplastia [acesso 2018 Set 5] 2006. Disponível em: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/33868/2492231/doc_alerta_953.pdf

8. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Agência de Vigilância Sanitária (Anvisa). Resolução - RE Nº 2.732, de 5 de setembro de 2007. Brasília: Diário Oficial da União; 2007 [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/33868/2492231/doc_alerta_955.pdf

9. Vargas AF, Amorim NG, Pitanguy I. Complicações tardias dos preenchimentos permanentes. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(1):71-81.

10. de Melo Carpaneda E, Carpaneda CA. Adverse results with PMMA fillers. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(4):955-63. DOI: 10.1007/s00266-012-9871-8 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-012-9871-8

11. Conselho Regional de Medicina do Paraná. PARECER Nº 2238/2010 CRM-PR. Processo Consulta Nº 107/2010. Assunto: Procedimento de Bioplastia de Glúteo. EMENTA: Bioplastia - Uso da Substância Polimetilmetacrilato (PMMA) [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: https://sistemas.cfm.org.br/normas/visualizar/pareceres/PR/2010/2238

12. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Agência de Vigilância Sanitária (Anvisa). Alerta de Segurança para a utilização do Produto POLIMETILMETACRILATO PMMA. Brasília: Anvisa; 2012 [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/resultado-de-busca?p_p_id=101&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=maximized&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-1&p_p_col_count=1&_101_struts_action=%2Fasset_publisher%2Fview_content&_101_assetEntryId=2633703&_101_type=content&_101_groupId=33868&_101_urlTitle=2633700&inheritRedirect=true

13. Requena L, Requena C, Christensen L, Zimmermann US, Kutzner H, Cerroni L. Adverse reactions to injectable soft tissue fillers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(1):1-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.064

14. Brasil. Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM). Processo-Consulta CFM Nº 70/12 - Parecer CFM Nº 5/13. Uso indiscriminado do polimetilmetacrilato (PMMA). EMENTA: Recomenda-se que o PMMA, quando utilizado, seja feito por médicos, em pequenas doses, pois o uso em grandes doses pode produzir resultados indesejáveis. Brasília: CFM; 2013 [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: http://www.portalmedico.org.br/pareceres/cfm/2013/5_2013.pdf

15. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP). Censo 2016. Situação da Cirurgia Plástica no Brasil. Análise Comparativa das Pesquisa 2014 e 2016. São Paulo: SBCP; 2017 [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/CENSO-2017.pdf

16. Aplicação de PMMA resulta em mais de 17 mil complicações em 2016. Plast Pau. 2016;60:24 [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: http://sbcp-sp.org.br/downloads/revista-plastica-paulista-2016-ed-60.pdf

17. Conselho Regional de Medicina do Estado de São Paulo (Cremesp), Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP), Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia (SBD). Nota de Agravo: CREMESP, SBCP e SBD pedem retratação à Anvisa sobre indicações do PMMA. São Paulo: Cremesp, SBCP, SBD [acesso 2018 Set 5]. Disponível em: http://www.sbd.org.br/noticias/nota-de-agravo-cremesp-sbcp-e-sbd-pedem-retratacao-a-anvisa-sobre-indicacoes-do-pmma/

18. Blanco Souza TA, Colomé LM, Bender EA, Lemperle G. Brazilian Consensus Recommendation on the Use of Polymethylmethacrylate Filler in Facial and Corporal Aesthetics. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(5):1244-51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-018-1167-1

19. Cassuto D, Pignatti M, Pacchioni L, Boscaini G, Spaggiari A, De Santis G. Management of Complications Caused by Permanent Fillers in the Face: A Treatment Algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(2):215e-27e. PMID: 27465182

20. Nácul AM, Valente DS. Complications after polymethylmethacrylate injections. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1):342-3. PMID: 19568132 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a83ac2

21. Milcheski DA, Ferreira MC, Nakamoto HA, Pereira DD, Batista BN, Tuma P Jr. Subatmospheric pressure therapy in the treatment of traumatic soft tissue injuries. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2013;40(5):392-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-69912013000500008

1. Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina,

Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Kleber Tetsuo Kurimori Rua Estela, nº 287, Apto 13 - Vila Mariana, São Paulo, SP, Brazil Zip Code 04011-001 E-mail: kleber.kurimori@gmail.com

Article received: October 18, 2018.

Article accepted: February 10, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter