Case Report - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Surgical resection of symptomatic calcinosis in a patient with systemic sclerosis

Ressecção cirúrgica de calcinose sintomática em paciente com esclerose sistêmica

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Systemic sclerosis is a rare, autoimmune, progressive disease that affects connective tissues and internal organs by inflammation, which can cause calcinosis cutis. It can progress to painful and disabling conditions, and can become infected, especially when skin ulceration is present.

Objective: To present a case of calcinosis in the inguinal region and its surgical recovery.

Case Report: A female patient with calcinosis in the bilateral inguinal region presenting with moderate/severe pain had a failed clinical treatment. We performed surgical resection of the calcinosis cutis, which had formed clusters of fibrosis with adhesion to the fascia of the external oblique muscle. We used simple nylon 2.0 sutures along the subdermal plane to perform primary closure and continuous nylon 3.0 sutures along the intradermal plane for aesthetic closure and minimal inflammatory reaction. Her postoperative recovery was positive.

Conclusion: The best treatment for calcinosis cutis is still unclear. Treating complications becomes essential for reducing patients' morbidity and increasing their quality of life.

Keywords: Sclerosis; Calcinosis; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Operative surgical procedures; Rheumatology

RESUMO

Introdução: A esclerose sistêmica é uma doença rara, autoimune, com evolução progressiva, que afeta os tecidos conectivos e órgãos internos por inflamação, podendo causar calcinose de subcutâneo. Podem evoluir para quadros dolorosos e incapacitantes, podendo tornar-se infectados, principalmente quando ulceram pela pele.

Objetivo: Apresentar caso de calcinose em região inguinal e sua evolução cirúrgica.

Relato de Caso: Paciente feminina portadora de calcinoses em região inguinal bilateral, apresentando algia moderada/grave com falha de tratamento clínico. Realizada ressecção cirúrgica das calcinoses, que formavam cordões de fibrose com aderência na fáscia do músculo oblíquo externo. Realizado fechamento primário com nylon 2.0 pontos simples subdérmicos e ponto intradérmico continuo nylon 3.0 para fechamento estético e menor reação inflamatória. Boa evolução pós- operatório.

Conclusão: O melhor tratamento da calcinoses ainda não é claro. O tratamento das complicações se torna essencial para reduzir a morbidade e aumentar a qualidade de vida do paciente.

Palavras-chave: Esclerose; Calcinose; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Procedimentos cirúrgicos operatórios; Reumatologia

INTRODUCTION

Systemic sclerosis is a rare, autoimmune, progressive disease that affects connective tissues and internal organs by inflammation, fibrosis, or vasculopathies1. It is more common in women (4:1), and its onset occurs between the ages of 30 and 50 years1. Calcinosis cutis is frequently found in systemic sclerosis, but its spectrum of presentations is reported anecdotally2.

When present, calcinosis can progress to painful, disabling conditions and may become infected, especially with skin ulcerations, requiring a surgical treatment approach3. As of now, calcinosis related to systemic sclerosis has received little attention in studies, including its pathogenesis and related diseases3. While surgical treatments for calcinosis cutis in hands and fingers have been reported, we found few studies about calcinosis cutis in other areas, such as the present case of calcinosis cutis in the inguinal region4.

CASE REPORT

A 53-year-old female patient was referred to and treated in the rheumatology department of the University Hospital of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (HU/UFSC) in Florianópolis, Santa Catarina. She was diagnosed as having systemic sclerosis 20 years before and presented with calcinosis in the bilateral inguinal region, which was suggestive of dystrophic calcinosis.

A surgical procedure to remove the calcium lesions was requested because of continuous moderate/severe pain without precipitating and relieving factors, and the risks of ulceration and infection from the progressive characteristic of the localized disease.

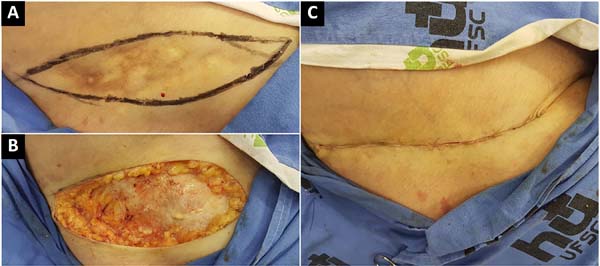

Clinical treatment with medication was given but failed to stop the progression of the calcinosis or attain remission. The patient took azathioprine and prednisone to stabilize the underlying disease and denied prior surgeries. In the physical examination, she presented with a hardened cluster of lesions adhered to the subcutaneous tissue in the inguinal region and bilateral flanks that were compatible with calcinosis and felt discomfort with light, passive movements. She showed no signs of localized infection or ulceration. The lesions covered an area of 20 × 5 cm (Figure 1). Ultrasonography of the inguinal region showed hyperechoic linear and irregular masses projecting from the subcutaneous tissue in the inferior area of the lateral abdominal wall, the largest ones being 36 mm in length, which were compatible with calcification.

Concerning the progressive state of the localized disease, the unsuccessful attempt at clinical drug treatment, and the patient’s considerable pain, surgical resection was indicated.

We marked the inguinal region, contemplating the entire affected area through palpation in the physical and imaging examination (a cutaneous site marking of approximately 15 × 4 cm). Local anesthesia was administered with 50 mL of solution containing 20 mL of 2% lidocaine, 1/120,000 adrenaline, and 100 mL of saline. We performed cutaneous and subcutaneous resections to remove the calcinosis, which had formed clusters of calcium lesions, some of which had adhered to the fascia of the external oblique muscle, without resection of the fascia or external oblique muscle.

We removed a single block containing cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues affected by the calcinosis. After hemostasis, we used simple nylon 2.0 sutures in the subdermal plane for primary closure and continuous 3.0 nylon sutures in the intradermal plane for aesthetic closure and minor inflammatory reaction (Figure 2).

The site was dressed with neomycin and mild cutaneous compression, and the dressing was to be changed daily after a bath. The patient adhered to the postoperative follow-up care, and the intradermal sutures were removed on the 12th day. At this time, the patient no longer presented with localized daily pain caused by calcinosis; thereby, a subjective analysis of the patient’s pain (preoperative and postoperative) was conducted.

In the second postoperative month, the patient’s condition progressed with the extrusion of a subdermal suture without the need for secondary surgery and without a surgical wound, other intercurrences, or complications.

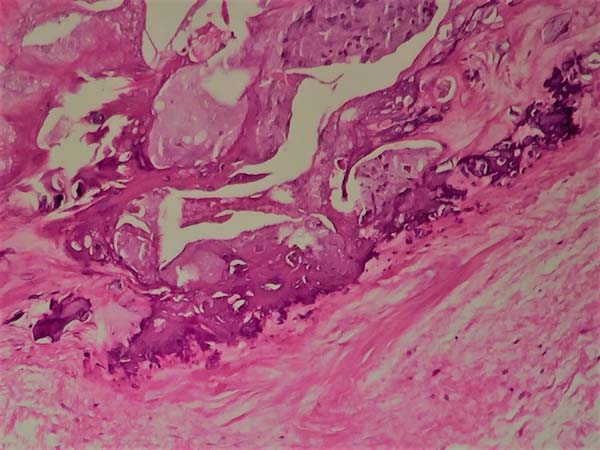

The photographs show a favorable aesthetic result on the 90th postoperative day (Figure 3). The histological evaluation demonstrated no degree of malignancy in the calcifications (Figure 4). The patient is currently under follow-up care by the plastic surgery department of HU/UFSC and did not present with new calcifications in the surgical area or atrophic scars during recovery.

DISCUSSION

Systemic sclerosis is a disabling disease that involves the interdisciplinary participation of physicians, as it indiscriminately affects all body systems. The rheumatologist is in charge of clinical follow-up, as it is a connective tissue disorder. However, the collaboration of other specialties sometimes becomes unquestionable5.

Calcification of soft tissue is generally categorized into four types, namely dystrophic calcification, metastatic calcification, idiopathic calcification, and calciphylaxis. In dystrophic calcification, serum calcium and phosphate levels are normal. This is commonly related to connective tissue diseases such as dermatomyositis and scleroderma5.

Calcinosis caused by systemic sclerosis is a condition in which the last treatment option is surgical resection because of the uncertainty of recovery from surgical trauma before the underlying disease. Drug treatment, which has not been standardized, seeks to contain the progression of calcinosis in terms of size and cutaneous ulceration. Drug intervention has provided mixed results in its effectiveness, and its results vary according to studies.

Calcium channel blockers have demonstrated the greatest efficacy among other drug interventions. They promote a decrease in the influx of calcium into the cell, thereby decreasing the formation of intracellular crystals. While colchicine does not affect the calcium lesions themselves, it reduces secondary inflammation6-9.

As in this case, some patients present moderate to severe pain due to the clusters of sensitive cutaneous innervations, which accelerate the search for their surgical treatments. Nonetheless, little information is available in the surgical literature on calcinosis in patients with connective tissue disease, particularly in the inguinal region, which is an unusual topography of the disease, as it normally occurs in the extremities and joints6,7.

Although risks of pain recurrence and additional calcification due to surgical trauma are present, treatment of calcinosis before it progresses to localized ulceration and infection is favorable7.

This case report serves as a reference for future research. The best treatment for calcinosis cutis is still unclear, as no fully effective treatment is available. We attempted clinical drug treatment to stop or slow disease progression. Surgical treatment is the last option because of uncertainties about recovery from surgical trauma2.

Consequently, treating complications becomes essential to reducing the patients’ morbidity and increasing their quality of life. In cases with an imprecise postoperative recovery, the physician-patient relationship should guide procedures to prevent future discontent of treatment outcomes.

COLLABORATIONS

|

CPG |

Conception and design study, methodology, project administration, writing - original draft preparation. |

|

NBR |

Data curation, writing - original draft preparation. |

|

CMM |

Data curation, writing - original draft preparation. |

|

FCNG |

Data curation. |

|

JBE |

Conceptualization, supervision, writing - review & editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Jecan CR, Bedereag SI, Sinescu RD, Grigorean VT, Cozma CN, Bordianu A, et al. A case of a generalized symptomatic calcinosis in systemic sclerosis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57(2 Suppl):865-9.

2. Vayssairat M, Hidouche D, Abdoucheli-Baudot N, Gaitz JP. Clinical significance of subcutaneous calcinosis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Does diltiazem induce its regression? Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(4):252-4. PMID: 9709184 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.57.4.252

3. Mahmood M, Wilkinson J, Manning J, Herrick AL. History of surgical debridement, anticentromere antibody, and disease duration are associated with calcinosis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45(2):114-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/03009742.2015.1086432

4. Selig HF, Pillukat T, Mühldorfer-Fodor M, Schmitt S, van Schoonhoven J. Surgical treatment of extensive subcutaneous calcification of the forearm in CREST syndrome. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(12):1817-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2013.06.035

5. Radu F, Nishiaoki M, Louis MA. Calcinosis Cutis and Negative Pressure Wound Therapy as Adjuncts to Surgical Management: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Wounds. 2018;30(3):E32-5.

6. Saddic N, Miller JJ, Miller OF 3rd, Clarke JT. Surgical debridement of painful fingertip calcinosis cutis in CREST syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(2):212-3. PMID: 19221282 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archderm.145.2.212-b

7. Mendelson BC, Linscheid RL, Dobyns JH, Muller SA. Surgical treatment of calcinosis cutis in the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2(4):318-24. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0363-5023(77)80136-6

8. Robertson LP, Marshall RW, Hickling P. Treatment of cutaneous calcinosis in limited systemic sclerosis with minocycline. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(3):267-9. PMID: 12594118 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.62.3.267

9. Harigane K, Mochida Y, Ishii K, Ono S, Mitsugi N, Saito T. Dystrophic calcinosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21(1):85-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/s10165-010-0344-0

1. Hospital Universitário, Universidade Federal de

Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Caio Pundek Garcia Madre Benvenuta, nº 322 - Trindade, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil Zip Code 88036-595 E-mail: caio_pgarcia@hotmail.com / caio@polski.com.br

Article received: March 23, 2018.

Article accepted: November 11, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter