Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 - Issue 1

Esthetic refinements to the appearance of the vulva in sex reassignment surgery

Refinamentos estéticos na aparência da vulva na cirurgia de adequação genital

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Sex reassignment surgery is a reliable and safe option, which has drastically reduced dysphoria and improved the quality of life of transgender individuals. The most studied and used technique is penile inversion with modifications, which results in appropriate esthetic appearance and functionality, but the surgical technique has not been standardized. Partial satisfaction rates up to 38% and dissatisfaction rates of 15% may cause up to 66% of cases to undergo additional procedures. The objective is to suggest esthetic refinements to the appearance of the vulva and compare some of the techniques described, seeking to increase the postoperative esthetic and functional satisfaction.

Methods: A retrospective study with 7 patients undergoing sex reassignment surgery between August 2017 and February 2018 was conducted. The clitoris is constructed with the glans in the form of a trident, using the corona to build the corpus cavernosa of the clitoris and increase the area of erogenous sensation. A section of the prepuce is used to increase the coverage of the clitoris and cover the inner surface of the labia minora, which are defined with the use of sutures.

Results: Adequate sensitivity and satisfaction with the result and capacity of orgasm in all patients were observed. There was no stenosis, fistula, or necrosis of the clitoris with this technique. Only 1 case needed an additional procedure for better esthetic definition.

Conclusion: The technique presented leads to high patient satisfaction and erogenous sensitivity, with some advantages compared to other techniques. However, prospective studies with larger numbers of patients are needed to define a more effective surgical technique.

Keywords: Vulva; Transsexualism; Transgender Individuals; Sex Reassignment Surgery; Sex Reassignment Procedures

RESUMO

Introdução: A cirurgia de adequação genital tem se mostrado uma opção segura e confiável, com redução drástica na disforia e melhora da qualidade de vida das pessoas transgênero. A técnica mais estudada e utilizada é a inversão peniana com suas modificações, com aparência estética e funcionalidade adequadas, porém sem padronização da técnica cirúrgica. Índices de até 38% de satisfação parcial e 15% de insatisfação podem levar até 66% dos casos a realizar procedimentos adicionais. O objetivo é sugerir refinamentos estéticos na aparência da vulva e comparar com algumas das técnicas descritas, buscando aumentar a satisfação estética e funcional pós-operatória.

Métodos: Estudo retrospectivo com 7 pacientes submetidas à cirurgia de readequação sexual entre agosto de 2017 e fevereiro de 2018. O clitóris é feito com a glande em formato de tridente, utilizando a coroa para construir os corpos cavernosos do clitóris e aumentar a área de sensação erógena. Faixa de prepúcio é usada para aumentar a cobertura do clitóris e cobrir a face interna dos pequenos lábios, que são definidos com o uso de suturas.

Resultados: Sensibilidade adequada e satisfação com o resultado e capacidade de orgasmo em todas as pacientes observadas. Não houve estenose, fístula ou necrose do clitóris com essa técnica. Somente 1 caso precisou de procedimento adicional para melhor definição estética.

Conclusão: A técnica apresentada tem alta satisfação das pacientes e sensibilidade erógena, com algumas vantagens em relação a outras técnicas. Porém, estudos prospectivos com número maior de pacientes são necessários para definir a técnica cirúrgica mais efetiva.

Palavras-chave: Vulva; Transexualismo; Pessoas Transgênero; Cirurgia de Readequação Sexual; Procedimentos de Readequação Sexual

INTRODUCTION

Transsexuality is a dynamic and biopsychosocial condition in which a person has the subjective feeling of belonging to a different gender than the anatomical gender (corresponding phenotype and genotype)1. These individuals have significantly lower quality of life indices compared to the general population, which is probably related to problems of personal self-esteem and a social character2.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) standardized principles based on evidence for the care of transgender individuals, both for the diagnosis and treatment, taking into account that gender correction surgeries are needed to alleviate gender dysphoria in these individuals3.

Accordingly, genital surgery is a safe and reliable option, which drastically reduces dysphoria and improves the quality of life4,5 in relation to psychological aspects and social relations, with an improved ability to develop relationships, greater professional acceptance, and greater feeling of integration into society6.

Transgender women who undergo genital surgery seek reconstruction of the external genitalia with appropriate esthetic appearance and functionality. Different techniques can accomplish this, including penile inversion techniques, scrotal flaps, scrotal grafts, non-scrotal grafts/flaps, and techniques that use the large intestine or peritoneum4.

The most studied and currently used technique is penile inversion4,7,8, which is recommended initially before recommending intra-abdominal techniques8. This technique involves dissection of the penile skin, formation of a neovaginal cavity between the rectum and bladder, and inversion of the skin in this cavity, and may use a full-thickness graft of the scrotal skin for the vaginal covering. Despite the differences in surgical details, the criteria for patient selection, and the evaluation of results8,9, this technique presents good results10, with an overall satisfaction index of 88%4.

From the functional point of view, satisfaction with the result is seen in more than 86% of the patients4,11,12, with more than 70% reaching an orgasm1,4,8,10,13.

Even so, additional procedures are often necessary to achieve the best possible result14,15. Additional corrections of the labia after surgery are needed in 43% of cases10 and other procedures in general in up to 66% of patients6, given that 28% to 38% of patients reported being only partially satisfied7 and 9% to 15% reported being dissatisfied with the results obtained1,7,9,11.

These indices can be even higher due to low rates of responses to quality of life questionnaires in several studies1. The esthetic and functional outcome of surgery seems to be the most important factor in the satisfaction or the repentance of the patients after the surgery5, determining the need for additional procedures.

However, the surgical technique or preoperative care16 have not been standardized, due to the lack of long-term follow-up of patients and few publications reporting refinements and technical advances17.

OBJECTIVE

This study proposes to suggest esthetic refinements to the appearance of the vulva, describing some parallels and limitations of some of the reported techniques, seeking to increase the postoperative esthetic and functional satisfaction. The author describes a series of 7 cases and the results of these technical modifications.

METHODS

A retrospective study with 7 patients operated with the technique described in this article, between August 2017 and February 2018, was held. The patients fulfilled the requirements of the Federal Council of Medicine for surgery in Brazil (older than 21 years of age, at least 2 years since gender transition, and follow-up with a multidisciplinary team consisting of a psychologist, psychiatrist, endocrinologist, social worker, and surgeon). Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Preoperative care

On the day before surgery, the patients are advised to have a residue-free diet during the day (without red meat, vegetables, fruits, carbonated drinks, or alcohol) and liquid diet at dinner. The intestinal preparation is done with two tablets of bisacodyl at lunch and two tablets at the end of the afternoon. At night, patients ingest 120 mL of lactulone diluted in 500 mL of filtered orange or lemon juice, which is ingested within 30 minutes, followed by oral hydration up to 8 hours before the scheduled time of surgery to prevent dehydration.

Surgical technique

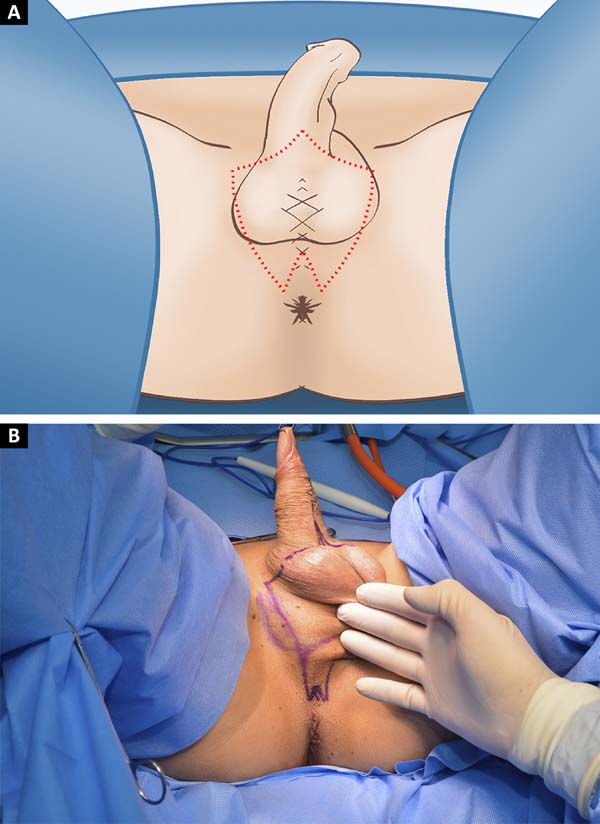

With the patient in the lithotomy position, a perineal and scrotal skin graft is withdrawn, preserving a 2 cm extension triangular perineal flap, at the level of the central tendon of the perineum (Figures 1A and 1B). Orchiectomy is performed with ligation of the inguinal cord at the level of the superficial inguinal ring. The urethra is separated from the corpus cavernosum using a catheter to guide its dissection and thebulbospongiosus muscle and excess corpus spongiosum are removed.

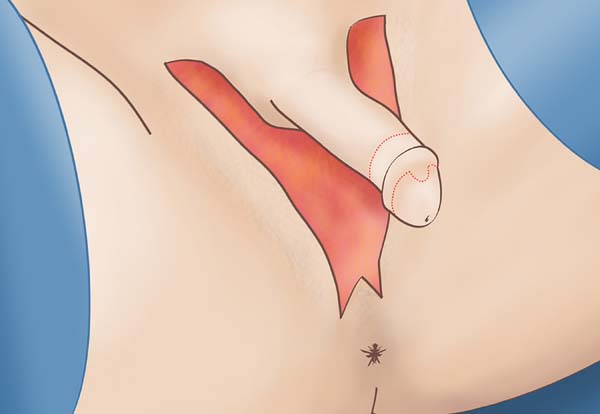

The glans is incised to prepare the clitoris in the form of a trident (Figure 2), including 1.5 cm of its dorsal portion in a rounded shape, extending laterally to the corona and the cervix of the glans up to the prepuce, preserving a range of proximal preputial skin of 1.5 cm. The tube of penile skin is separated from the penile shaft, preserving its pedicle.

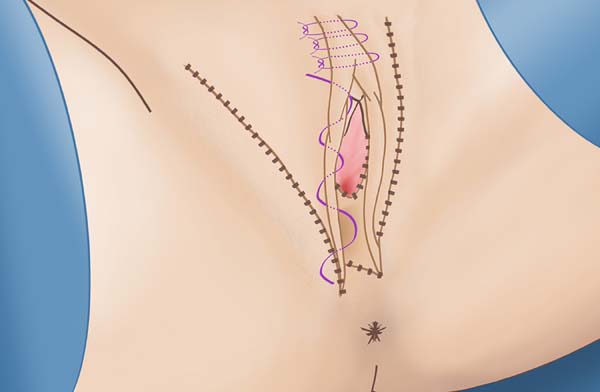

The tunica albuginea is incised laterally and included together with the neurovascular pedicle, being separated from the corpora cavernosa, which are ligated at its base and removed. The suture of the trident lateral regions near the central flap in its most proximal portion is performed with vicryl 3.0, which simulates the corpora cavernosa of the clitoris and defines the clitoral glans in the central region. The entire flap is folded over and fixed in the pubic symphysis. The urethra is spatulated, with its distal portion resected in a triangular shape, which is attached anteriorly to the clitoris with vicryl 3.0, between the distal portions of the lateral flaps of the trident (Figure 3).

The construction of the vaginal canal is performed using a combination of blunt dissection with electrocautery, through the central tendon of the perineum and the Denonvilliers’ fascia. The rectal wall is protected posteriorly by one of the hands of the surgeon, while the other hand performs the dissection and the assistant uses an enlightened valve to move anteriorly the urethra and the penile tissue. The vaginal cavity is dissected by about 15 cm deep.

The removed scrotal skin is prepared as a total skin graft and sutured in a pouch to the penile flap. The hair follicles are individually cauterized and, after hemostatic review, the penile flap is invaginated and inserted into the cavity. The posterior skin of this flap is opened to accommodate the perineal flap. Suction drainage is used to prevent fluid accumulation between the flap/graft and the canal, which is held in place by a vaginal tamponade of gauze soaked in metronidazole and bacitracin cream.

The exteriorization of the clitoris and the labia minora is performed by incising the penile flap at the midline at the height of the clitoris until immediately below the urethral ostium. The lower region of the urethral stump and the preputial skin of the clitoris are sutured to the penile skin with vicryl 3.0. In order to define the anterior commissure of the lábia and the clitoral prepuce, 3 transdermal running sutures are made cranially to the clitoris with vicryl 3.0, with an inlet and an outlet opening 1 cm from the midline (Figure 3). A Greek bar suture is performed to define the labia minora from the height of the clitoris to the vaginal ostium with vicryl 3.0 (Figure 3). The excess scrotal skin is resected and the skin closed in 3 planes (Figures 4A and 4B), followed by compressive dressing.

Postoperative care

The patient is kept at absolute rest for 24 hours. The dressing is removed on the second day and walking is encouraged. On the third day, the drain is removed and the patient is discharged from the hospital with a urinary probe and a vaginal plug. The patient returns between the 7th and 10th day, when the vesical catheter and the vaginal tampon are removed and postoperative dilatations are initiated.

RESULTS

The mean age of the 7 patients was 28.3 ± 6.8 years. The only relevant medical history was hypothyroidism (n = 1) and HIV infection1, both of which were adequately clinically controlled. None of the patients were smokers. Surgical history included augmentation mammoplasty (n = 4) and facial feminization (3), with 1 patient without any previous surgeries. All patients had undergone previous hormonal treatment. The mean depth reached in the dissection of the vaginal canal was 15.14 ± 0.73 cm. The hospital stay was 3 days in all cases.

Among the complications, 1 case needed additional surgery for correction due to the loss of definition of the anterior commissure and higher clitoral exposure than desired (Figure 5). The more serious complications were postoperative bleeding (n=1), which required blood transfusion and cauterization of the bleeding vessel, and a rectal lesion (1), which was intraoperatively repaired. There was no fistula or stenosis in this group of patients, nor was there a partial or total necrosis of the clitoris.

No patient presented with complaints related to vulvar sensitivity and all reported being satisfied with the surgery and being able to reach orgasm after 3 months of the procedure.

DISCUSSION

Georges Burou and Harold Gillies are known for their description of the penile inversion technique in transgender women in 1950s7,18, with the inclusion of a scrotal flap by Howard Jones18. The classic procedure of choice for clitoral reconstruction is to use the glans (total or partially) as a neurovascular pedicle flap in island, described by Hinderer19 and modified by Brown20. The inclusion of the tunica albuginea21 is technically simple and decreases the risk of nerve injury.

The basic steps of the penile inversion technique involve: orchiectomy, penile disassembly, creation of the vaginal cavity between the rectum and bladder, reconstruction of the clitoris and orthotopic female urethral meatus, and creation of the labia majora16. Adequate urogenital function and an attractive esthetic result should be sought from the genitals, which are key factors for a high rate of satisfaction of patients submitted to surgery14.

This includes adequate urethral positioning to foster a straight jet of urine, with an appropriately wide and deep vagina for sexual intercourse and with adequate sensitivity to experience orgasm, and the use of the whole tissue available for this is recommended14. Modern techniques with the preservation of tissues showed best indices of sexual function compared to the simple penile inversion in standardized questionnaires22, which reinforces this recommendation. Thus, in patients with a small penis and without the use of additional coverage of the vaginal cavity, the esthetic result will depend on the chosen neovaginal depth, which is resolved with the use of skin grafts7.

The main objectives of an optimal clitoridoplasty are as follows: reproducible, reliable, and safe single stage technique; appropriate clitoris size under normal functional conditions; reconstruction of the anatomical structure with erectile tissue preserving its erogenous innervation; presence of mucous or epithelial tissue in the vestibular region and around the clitoris; absence of painful or withdrawn scars; and presence of frenulum and preputial covering23.

The sensitivity of the clitoris is important as a pre-requisite likely to achieve the sexual orgasm13. When the dorsal region of the glans is used for the clitoris, a greater stimulus intensity is required for light touch and pressure stimuli than in cisgender women with comparable vibration sensitivity12.

Similar results were obtained in another study13, which emphasized the common occurrence of hypersensitivity of the clitoris and the need for a clitoral hood to protect it from the hyperstimulation caused by clothes and movement. The technique of the author addresses both of these needs, increasing the area of erogenous sensation to include the region of the corona of the glans and prepuce to the dorsal flap, and at the same time the clitoris also being surrounded by the foreskin and cranially approximated skin.

The anatomical basis for the creation of the dorsal neurovascular flap using the author’s technique has already been described. Small branches parallel to the dorsal nerve of the penis run along the dorsolateral surface of the penis and penetrate posteriorly in the whole area of the penile corona24. Immediately below the lateroventral corona of the penis, the dorsal nerve is divided in four branches: a proximal branch heading dorsally in the direction of the coronal tissue, a branch diverging (laterally to medially) to the central parenchyma of the glans, and two other branches diverging laterally and ventrally toward the ventral region23.

To increase the sensitivity of the clitoris, it is suggested that the Buck fascia be incised laterally, starting at the base of the penis and the elevation of the neurovascular pedicle be made deeply to the tunica albuginea of the corpus cavernosum24. This preserves more nerve fibers, which run dorsolateral 1.5 to 2 cm from the midline in the erect penis23.

Techniques using the region of the corona of the glans to increase the surface area and the erogenous sensory potential of the clitoris have already been described. Clitoridoplasty using the ventral region of the glans25 would lead to a more complete erogenous sensation compared to that using the dorsal region by following the anatomical direction of the nerves in the glans, including the two lateroventral branches of the dorsal nerve23.

Another technique described uses a bifid and symmetrical flap of the corona of the glans in the shape of a lotus flower23, preserving the preputial skin in the flap and positioning the urethra in a manner similar to that described here. The author’s criticism of this technique is the excessive anteroposterior elongation of the clitoris, which does not present the ideal clitoral shape from the esthetic point of view and which decreases the vestibular area above the urethral meatus. In addition, this technique involves the removal of oval-shaped skin (5.0 x 4.0 cm) from the dorsal region of the penile flap to externalize the clitoris and urethra, which decreases the amount of tissue available to define the labia minora and may increase clitoral exposure.

A very similar technique to that of the author is used for years in Thailand26, with the preparation of a flap in M preserving preputial skin, which is folded over itself to make the labia minora. An appraisal of the author to this technique is that the small labia minora are made only to the height of the urethral meatus, which would be the maximum length of the lateral M flaps and the adjacent prepuce, and not to the lateroposterior region of the vaginal introitus as is expected in the vulvar anatomy.

Accordingly, the definition of the labia minora subsequently depends exclusively on the excess skin of the penile flap. The author also prefers the rounded shape of the central region of the trident, as bringing it from the lateral flaps forms a discreet anterior projection, building the clitoris more reliably (a technique demonstrated by Marci Bowers to the author, in the 1st half of 2014). In the author’s view, the approach to expose in block the clitoris/urethra decreases the risk of urethral stenosis and preserves a greater quantity of skin for preparation of the labia minora.

Preputial skin can be used to define the labia minora, as described in the previous paragraph, but the most common approach is to use the lateral and proximal part of the penile flap. Some authors perform this procedure in a second stage, some months after the vaginoplasty14. Thus, zetaplasty can be used in the pubic region for the advancement of the labia minora18 or for clitoral coverage and labial convergence13,27. The use of sutures to define the labia minora has been described28.

As held by the author, the preputial skin is sutured to the longitudinal opening of the penile flap, forming the inner wall of the labia minora. The Greek bar suture from the clitoris to the posterior region of the vaginal meatus helps better define the labia minora (a technique demonstrated by Marci Bowers to the author, in the 1st half of 2014). Similarly, the approximation of the cranial skin toward the clitoris in the direction of the midline defines the anterior commissure and the clitoral prepuce, protecting it from tactile hyperstimulation.

Some of the techniques use a long scrotal flap to prepare the posterior vaginal wall7,23,26,27,29. The author has experience with this type of longer flaps and believes (as the authors of these techniques) that the posterior commissure suture line should be interposed with a flap to avoid stenosis, but currently prefers a short flap to avoid growth of hair in the vagina.

There is a progressive improvement in the timing of the perception of the esthetic result by patients and medical staff due to the improvement in postoperative edema and the healing of surgical wounds29, which was also verified by the author (Figures 6 and 7).

The satisfaction with surgery reported by patients was excellent and higher than that reported earlier1,4,10,11, although the small number of patients makes it impossible to perform a statistical comparison and some studies do not specify the technique used. The same is the case with the sensitivity and the ability of patients to achieve orgasms.

Some reports indicate that more than half of the patients operated on show a greater intensity of orgasms compared to the preoperative period1. Other factors may be associated with sexual satisfaction and may contribute to the overall well-being, such as stability and satisfaction with relationships, acceptance of body image, mood disorders, and physical health6,7.

CONCLUSION

The esthetic refinements defended in this article by the author and proposed by the surgeons who preceded him seek the closest possible results of sex reassignment surgery to the female anatomy and proper vaginal function, presenting high levels of satisfaction and sensitivity. This area is constantly evolving, but obviously has its limitations. Patients must always be aware that additional procedures are often necessary to achieve the best possible result15, and their expectations, often unrealistic and unattainable, must be adjusted.

Due to the significant dissemination of information on and awareness of transgenderism, studies on sex reassignment surgeries are advancing at a higher pace14, but more prospective studies are needed, as well as standardization of surgical procedures and long-term follow-up with larger numbers of patients to identify the most effective techniques for better aesthetic and functional results and greater satisfaction of patients, among the various technical variations and preferences of the surgeons.

REFERENCES

1. Hess J, Rossi Neto R, Panic L, Rübben H, Senf W. Satisfaction with male-to-female gender reassignment surgery. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(47):795-801. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2014.0795

2. Kuhn A, Bodmer C, Stadlmayr W, Kuhn P, Mueller MD, Birkhäuser M. Quality of life 15 years after sex reassignment surgery for transsexualism. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1685-9.e3.

3. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, De Cuypere G, Feldman JL, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13(4):165-232. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

4. Manrique OJ, Adabi K, Martinez-Jorge J, Ciudad P, Nicoli F, Kiranantawat K. Complications and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Male-to-Female Vaginoplasty-Where We Are Today: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2018;80(6):684-91. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000001393

5. Lawrence AA. Factors associated with satisfaction or regret following male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32(4):299-315. PMID: 12856892 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024086814364

6. Cardoso da Silva D, Schwarz K, Fontanari AM, Costa AB, Massuda R, Henriques AA, et al. WHOQOL-100 Before and After Sex Reassignment Surgery in Brazilian Male-to-Female Transsexual Individuals. J Sex Med. 2016;13(6):988-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.370

7. Buncamper ME, van der Sluis WB, de Vries M, Witte BI, Bouman MB, Mullender MG. Penile Inversion Vaginoplasty with or without Additional Full-Thickness Skin Graft: To Graft or Not to Graft? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(3):649e-56e.

8. Horbach SE, Bouman MB, Smit JM, Özer M, Buncamper ME, Mullender MG. Outcome of Vaginoplasty in Male-to-Female Transgenders: A Systematic Review of Surgical Techniques. J Sex Med. 2015;12(6):1499-512. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12868

9. Sutcliffe PA, Dixon S, Akehurst RL, Wilkinson A, Shippam A, White S, et al. Evaluation of surgical procedures for sex reassignment: a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(3):294-306. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2007.12.009

10. Buncamper ME, Honselaar JS, Bouman MB, Özer M, Kreukels BP, Mullender MG. Aesthetic and Functional Outcomes of Neovaginoplasty Using Penile Skin in Male-to-Female Transsexuals. J Sex Med. 2015;12(7):1626-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12914

11. Lobato MI, Koff WJ, Manenti C, da Fonseca Seger D, Salvador J, da Graça Borges Fortes M, et al. Follow-up of sex reassignment surgery in transsexuals: a Brazilian cohort. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35(6):711-5. PMID: 17075731 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9074-y

12. LeBreton M, Courtois F, Journel NM, Beaulieu-Prévost D, Bélanger M, Ruffion A, et al. Genital Sensory Detection Thresholds and Patient Satisfaction With Vaginoplasty in Male-to-Female Transgender Women. J Sex Med. 2017;14(2):274-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.12.005

13. Sigurjónsson H, Möllermark C, Rinder J, Farnebo F, Lundgren TK. Long-Term Sensitivity and Patient-Reported Functionality of the Neoclitoris After Gender Reassignment Surgery. J Sex Med. 2017;14(2):269-73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.12.003

14. Papadopulos NA, Zavlin D, Lellé JD, Herschbach P, Henrich G, Kovacs L, et al. Combined vaginoplasty technique for male-to-female sex reassignment surgery: Operative approach and outcomes. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70(10):1483-92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2017.05.040

15. Papadopulos NA, Zavlin D, Lellé JD, Herschbach P, Henrich G, Kovacs L, et al. Male-to-Female Sex Reassignment Surgery Using the Combined Technique Leads to Increased Quality of Life in a Prospective Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(2):286-94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003529

16. Dreher PC, Edwards D, Hager S, Dennis M, Belkoff A, Mora J, et al. Complications of the neovagina in male-to-female transgender surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis with discussion of management. Clin Anat. 2018;31(2):191-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23001

17. Wroblewski P, Gustafsson J, Selvaggi G. Sex reassignment surgery for transsexuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20(6):570-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.med.0000436190.80104.56

18. Jarolím L, Šed ý J, Schmidt M, Naňka O, Foltán R, Kawaciuk I. Gender reassignment surgery in male-to-female transsexualism: A retrospective 3-month follow-up study with anatomical remarks. J Sex Med. 2009;6(6):1635-44. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01245.x

19. Hinderer UT. Reconstruction of the external genitalia in the adrenogenital syndrome by means of a personal one-stage procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84(2):325-37. PMID: 2748745 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198908000-00022

20. Brown J, Wesser D. A single-stage operative technique for castration, vaginal construction and perineoplasty in transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav. 1978;7:313.

21. Fang RH, Chen CF, Ma S. A new method for clitoroplasty in male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89(4):679-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199204000-00015

22. Zavlin D, Schaff J, Lellé JD, Jubbal KT, Herschbach P, Henrich G, et al. Male-to-Female Sex Reassignment Surgery using the Combined Vaginoplasty Technique: Satisfaction of Transgender Patients with Aesthetic, Functional, and Sexual Outcomes. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(1):178-87. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-017-1003-z

23. Giraldo F, Esteva I, Bergero T, Cano G, González C, Salinas P, et al. Corona glans clitoroplasty and urethropreputial vestibuloplasty in male-to-female transsexuals: the vulval aesthetic refinement by the Andalusia Gender Team. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6):1543-50. PMID: 15509947 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000138240.85825.2E

24. Tansatit T, Jindarak S, Sampatanukul P, Wannaprasert T. Neurovascular anatomy of the penis and pelvis in Thai males: applications to male-to-female and pelvic surgeries. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90(1):121-8. PMID: 17621742

25. Szalay L. Construction of a neoclitoris in male transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(2):425. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199502000-00046

26. Wangjiraniran B, Selvaggi G, Chokrungvaranont P, Jindarak S, Khobunsongserm S, Tiewtranon P. Male-to-female vaginoplasty: Preecha's surgical technique. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2015;49(3):153-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/2000656X.2014.967253

27. Schechter LS. Surgical Management of the Transgender Patient. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.

28. Reed H. Aesthetic and functional male to female genital and perineal surgery: feminizing vaginoplasty. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25(2):163-74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1281486

29. Buncamper ME, van der Sluis WB, van der Pas RS, Özer M, Smit JM, Witte BI, et al. Surgical Outcome after Penile Inversion Vaginoplasty: A Retrospective Study of 475 Transgender Women. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(5):999-1007. PMID: 27782992 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002684

1. Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André, SP,

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Matheus Zamignan Manica Rua Tenente Gomes Ribeiro, nº 78, cj 114 - Vila Clementino, São Paulo, SP, Brazil Zip Code 04038-040 E-mail: contato@drmatheusmanica.com.br

Article received: June 12, 2018.

Article accepted: August 7, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter