Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Impact of aesthetic mammoplasty on the self-esteem of women from a northeastern capital

Impacto da mamoplastia estética na autoestima de mulheres de uma capital nordestina

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The main reason that leads someone to undergo aesthetic surgery is the need to obtain approval and affection from other people, which, consequently, enhances self-esteem. This study compared the level of self-esteem between the different types of mammoplasty and measured the degree of interference in the self-esteem of women undergoing aesthetic mammoplasty and the level of satisfaction after surgery.

Methods: A prospective, longitudinal, analytical, qualitative-quantitative study was held with 40 patients undergoing primary aesthetic mammoplasty. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was used together with questionnaires on psychosocial aspects in the pre- and post-operative period of two months. Associations were evaluated by Fisher's exact test. Differences in means were evaluated by a univariate analysis of variance (independent samples), and bivariate analysis (matched sample). The level of significance was 5%, and the software used was R Core Team 2017.

Results: Breast reduction, breast implantation, mastopexy, and association between mastopexy and breast implantation accounted for 45%, 30%, 12.5%, and 12.5% of cases, respectively. The majority expressed being dissatisfied with their body before surgery and indicated the breasts as the major reason. The desire to raise self-esteem was the main motivation among the group. A high level of post-surgical satisfaction was observed among the participants, with surgery interfering in the professional, personal, and sexual aspects.

Conclusion: There was an average increase in the self-esteem of the participants who underwent mammoplasty, and the three types of surgery yielded similar results regarding the variation of self-esteem.

Keywords: Patient satisfaction; Self concept; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Mammaplasty; Quality of life

RESUMO

Introdução: O principal motivo que leva alguém a submeter-se à cirurgia estética é a necessidade de obter aprovação e afeto de outras pessoas, o que, consequentemente, melhora sua autoestima. Este estudo comparou o nível de autoestima entre os diferentes tipos de mamoplastia e mensurou o grau de interferência na autoestima das mulheres submetidas à mamoplastia estética e o nível de satisfação pós-cirúrgico.

Métodos: Estudo prospectivo, longitudinal, analítico, quali-quantitativo com 40 pacientes submetidas à mamoplastia estética primária. Foi utilizada a Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg e questionamentos sobre aspectos psicossociais no pré e pós-operatório de dois meses. As associações foram avaliadas pelo teste Exato de Fisher. As diferenças de média foram avaliadas por meio da Análise Variância univariada (amostra independente) e bivariada (amostra pareada). O nível de significância foi de 5% e o software utilizado foi o R Core Team 2017.

Resultados: Redução da mama, implante mamário, mastopexia e associação entre mastopexia com implante mamário totalizaram 45%, 30%, 12,5% e 12,5%, respectivamente. A maioria mostrou-se insatisfeita com o corpo no pré-cirúrgico e apontou a mama como maior incômodo. O desejo de elevar a autoestima mostrou-se como a principal motivação entre o grupo. Por fim, foi alto o nível de satisfação pós-cirúrgico entre as pacientes, tendo a cirurgia interferido em aspectos profissionais, pessoais e sexuais.

Conclusão: Houve aumento médio na autoestima das pacientes submetidas à mamoplastia e os três tipos de cirurgia produziram iguais resultados quanto à variação de autoestima.

Palavras-chave: Satisfação do paciente; Autoimagem; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Mamoplastia; Qualidade de vida

INTRODUCTION

There is an endless quest for perfect bodies in contemporary society. Personal satisfaction and physical well-being are an essential part of quality of life1. In contrast to the excessive effort to obtain the ideal body, the emergence of plastic surgeries presented another possibility: achieving a perfect body rapidly2,3.

The search for standards of beauty is linked to dubious diets and uncontrolled surgical procedures. The excessive desire for a harmonious appearance can hide psychosomatic phenomena, such as bulimia and anorexia, and other psychopathological traits, such as Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)4.

According to researchers int his field, aesthetic surgery interferes directly and positively in the self-esteem of patients who do not have severe BDD, as well as improves their lives in the psychosocial aspect5. Given that the abovementioned are psychological disorders, they must be perceived as a kind of affliction, and plastic surgery, therefore, must be perceived as an appropriate therapeutic treatment in some cases6.

Brazil is the second country in the world that performs the most plastic surgeries; some of the most common procedures are liposuction, dermolipectomy, mastopexy, prosthesis, and breast reduction7.

Women tend to evaluate more positively the gains of the surgery than men because they internalize more media messages about beauty and, therefore, undergo more procedures, among them, aesthetic mammoplasty.

The main reason for aesthetic mammoplasty is to address disproportional breasts or severe ptosis, perceived as defective. Augmentation mammoplasty alternates between the first and second most commonly performed plastic surgery in Brazil and the world, as the breast is a symbol of femininity, maternity, and sexuality, and therefore, its augmentation carries high expectations and often promotes improvement in quality of life8,9.

A lack of knowledge and opportunity for a new study was perceived, given that there are few studies measuring the degree of interference in the self-esteem of women specifically seeking cosmetic mammoplasty. Few studies have compared the level of self-esteem between the different types of mammoplasty.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to measure the impact of aesthetic mammoplasty on the self-esteem of women, to shed light on the level of expectation and motivation in the pre- and post-operative period, as well as satisfaction in the post-operative period.

METHODS

Population and sample

This longitudinal prospective study evaluated a population of 40 women. The inclusion criteria for this study were women who underwent primary aesthetic mammoplasty at two private plastic surgery clinics in a capital city in Northeastern Brazil.

Data collection

The initial data collection was performed from December 2016 to January 2017. To answer the pre-surgical procedure questionnaire, the participants were approached in the waiting rooms of surgeons’ offices in the last pre-operative consultation. The participants received information about the research objectives and then signed the informed consent form.

Two months after surgery, there was a follow-up and a new application of the questionnaire, in which specific questions on the level of satisfaction in the post-operative period, interference with activities, and desire to perform another surgery were added. In both moments, they were at total liberty to question and clear their doubts. This study was approved by the ethics and research committee of Tiradentes University, Aracaju, Sergipe, with CAAE number: 629097 16.1.0000.5371.

Study site

Data collection was conducted in two private plastic surgery clinics located in Aracaju, state of Sergipe, namely, the Clínica Integrada Homo and Clínica Concept. Subsequently, the data analysis and drafting of the manuscript was performed at the Tiradentes University, also in Aracaju, state of Sergipe.

Questionnaire

Self-esteem was assessed using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. The scale is internationally validated and widely used for assessing self-esteem. It is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of ten close-ended sentences, with five referring to positive self-image and five to negative self-image, using a four-point Likert scale. The options indicate the degree of disagreement or agreement with the proposed sentence: 0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = agree, 3 = strongly agree.

The interpretation of the sum of all items of the scale (crude score) should be made with a table of standards appropriate to sex and age. The crude score corresponding to the 15th percentile should be equivalent to a standard deviation (SD) below the mean. The 85th percentile should correspond to an SD above the mean. Scores that fall below the average indicate low self-esteem, and those above the average correspond to high self-esteem.

Data analysis

The collected data were described by means of simple frequencies and percentages when categorical variables, or mean and standard deviation when continuous, discrete, or ordinal. The associations were evaluated with Fisher’s exact test. The differences in means were evaluated by the univariate analysis of variance (independent samples) and bivariate analysis (matched sample). The level of significance was 5%. R Core Team2017 was used to run the analyses.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

The study sample consisted of 40 female participants with a mean age of 32.825± 10.8531.

With regard to professional work, 84.8% reported being active in the labor market. As to the level of schooling, 46.1% had completed higher education and 35.9% high school; 7.7% completed and 10.3% did not complete primary schooling.

Motivations, proposals, and influences for completion of surgery

The primary motivation for the completion of the surgical procedure, considering all types of mammoplasty in the current study, was the desire to raise self-esteem. This motivation was found in 37.5% of the participants. When asked about who suggested surgery, 85% reported that the decision was their own initiative. In 22.5% of cases, it was by suggestion of friends and 10% of relatives.

Among the 40 participants, 57.5% reported that the main influence was the need for personal acceptance.

Need for a social explanation on the surgical procedure performed

Regarding the option to inform people on the surgical intervention, only 7.5% would not provide any information.

Post-surgical satisfaction

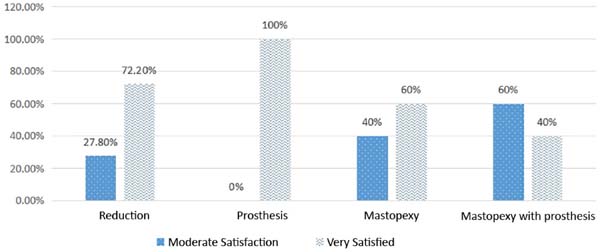

With regard to post-surgical satisfaction regarding the breasts, 25.6% reported moderate satisfaction and 74.4% reported high satisfaction. Among the 40 participants, one preferred to refrain from responding. Figure 1 shows the relationship between satisfaction and the types of mammoplasty.

Pre-surgical score of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

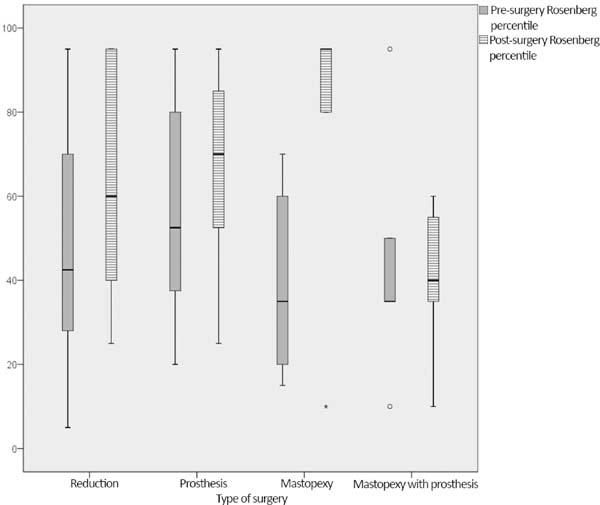

In the pre-surgical period, the participants had a crude score of 32.1 ± 5.3. The mean of the pre-surgical percentile was 50 ± 26.5.

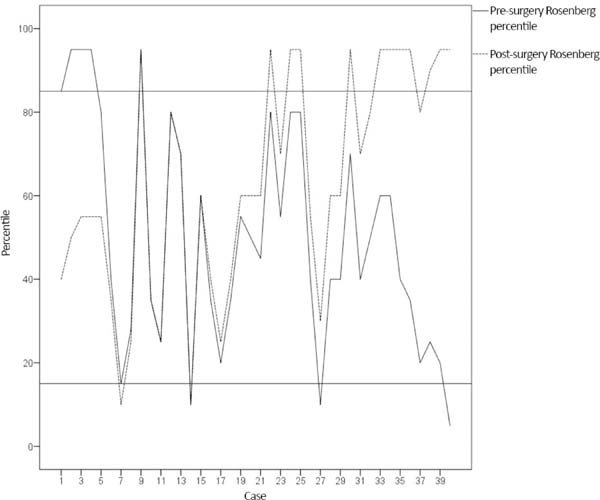

Only 10% had low self-esteem (percentile < 15) in the pre-surgical period.

Post-surgical score of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

In the post-surgery period, the participants had a gross score of 34.9 ± 4.6. The mean post-surgical percentile was 63.3 ± 26.6.

Of the participants who had low self-esteem (percentile < 15) in the pre-surgical period, 50% passed to average or high self-esteem, and one of them passed from the 5th in the pre-surgical period to 95th percentile in the post-surgical period.

Variation in pre- and post-surgical scores on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

There was a general increase of 13.3% (variation shown in Figure 2), considered average in accordance with Cohen’s Test, in the self-esteem of participants undergoing aesthetic mammoplasty (p = 0.009). Considering the type of mammoplasty performed, the variation can be seen in Figure 3.

Interference of mammoplasty in personal, professional, and/or social life

In 25.6% of participants, the result of plastic surgery did not interfere in their personal, professional and/or social life. For 74.4%, surgery interfered positively and in different ways. There was an increase of 51.3% in self-esteem, improvement in appearance in 12.8% and greater social acceptance in 10.3% of participants. One of the participants preferred to abstain from responding.

The surgery interfered in a positive manner on the aspects addressed in 44.4% of the participants who underwent mastopexy, in contrast to 83.33% of those who did not have the procedure (p = 0.032).

Interference in the sexual life

In relation to the interference caused by the surgery in sexual life, 60% reported a positive influence; 20% reported a moderate level and 40%, high. Meanwhile, 5% reported a negative interference: 2.5% reported a low negative impact and 2.5%, moderate. There was no interference in the sexual life for 30% of the participants, and 5% reported that they had no sex life.

DISCUSSION

The mean age of the individuals included in our study was 32.825 ± 10.8531 years (minimum age 18 years and maximum of 58), characterizing a similar sample of women who undergo these procedures based on data reported in the 2005 Census of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (2016).

We observed a general increase in the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale of 13.3 percentile in the self-esteem of participants attributed to aesthetic mammoplasty (p = 0.009), which is an average increase according to the Cohen’s test. This result is consistent with the fact that plastic surgery is considered an adequate therapy for the improvement of self-esteem6. Moreover, it corroborates a previous study that demonstrated how intervention in body image results in improvements in the quality of life and biopsychosocial aspects of patients, with a statistical correlation (p < 0.005) between general health: 90 patients at the Ivo Pitanguy Institute reported increased self-esteem in the post-operative period and positive influence on their relationships8.

Several authors have also reported how body satisfaction reflects on the quality of life and emotional and social performance of the individual in society. The quest for beauty through plastic surgery is associated with an aim of change in acceptance and social position10-12.

Although the average pre-surgical percentile in this study was 50 ± 26.5, i.e., the majority of women already had average self-esteem, there was a gain in the post-surgical percentile, with an average of 63.3 ± 26.6. Only 10% had low self-esteem (percentile < 15) before surgery. These participants could represent the population of women with BDD who request plastic surgery. As they do not believe they suffer from a mental disorder, these women, before looking for a psychologist or psychiatrist, seek out plastic surgeons. In the post-operative period, 50% left the low self-esteem zone and 50% remained.

In a literature review of prospective studies on patients with BDD seeking plastic surgery, Brito et al.5 concluded that patients with mild BDD could also benefit from the results of cosmetic surgery.

A study of 115 women divided into groups based on the number of surgeries performed and response to the Body Shape Questionnaire and Sociocultural Attitudes Questionnaire Regarding Appearance reported that 30.43% of the women who had already performed more than one surgical procedure indicated being dissatisfied with their body image; the study concluded that this result may be a reflection of the presence of traces of BDD verified in the study participants, as in the post-surgical period of women with severe BDD, the real or imaginary defects remained4. If the surgeons are not aware of the symptoms of the disease, they can re-operate these patients, but may always obtain a negative outcome in relation to the post-operative satisfaction of these patients.

The two participants in the present study that continued to report low self-esteem in the post-surgical period indicated moderate satisfaction with the results. In addition to the possibility of undiagnosed BDD, it is reasonable to think that the experience and external factors experienced by the participant may have altered this personal recognition after surgery. One possibility would be that the participants did not understand the items requested by the data collection instrument, although this seems less likely because these two participants completed higher education.

The literature describes the importance of investigating motivations and influences on the indication of aesthetic surgery13. Individuals who seek aesthetic surgery for purely temporal and external reasons may not be able to assess and understand the long-term risks and benefits of the surgery. Surgeons need to discuss and understand the feelings and expectations of patients related to surgery and make them understand that it is impossible to control the feedbackthey receive on their altered appearance.

According to the present study, the majority of the participants sought mammoplasty for internal reasons, as the main motivation for performing the surgical procedure was the desire to raise their self-esteem (37.5%). The majority (85%) stated that the choice of surgery was their own initiative, and 57.5% reported that the main influence was the need for acceptance. Comparing the motivations with the post-surgical satisfaction, the data found are consistent with the literature: of the participants who responded on post-surgical satisfaction, all were satisfied with the results (25.6% reported moderate satisfaction and 74.4%, high satisfaction).

However, a relevant result in this sample was that 92.5% responded that they would have social satisfaction with the procedure performed, which proves the necessity to obtain approval and more affection from other people. In addition, for 32.5% of the cases, the decision of undergoing the surgical procedure was upon the suggestion of friends or family.

Foustanos et al.14 obtained similar results, and their findings were confirmed by this study. A project, by means of a questionnaire on self-image, self-confidence, and work environment applied to 100 women who underwent aesthetic plastic surgery, also reported that appearance influences professional development and that social praise affects confidence at work14. In the present study, 84.8% of the participants reported having a profession. Therefore, enhancing physical appearance was reflected as gaining vigor, youth, and self-confidence necessary for professional self-assertion.

This study also showed that the three types of surgery (breast reduction, breast implantation, and mastopexy) produced the same outcome in self-esteem variation. Reductive surgery, in addition to the aesthetic issue, brings relief to the physical discomfort caused by large breast volumes. Based on this principle, we can imagine that reductive surgery would bring a higher gain in the variation of self-esteem. However, this hypothesis was not tenable, considering that surgeries of only an aesthetic nature are as impactful in improving the quality of life and biopsychosocial aspects of participants as reparative surgeries.

In relation to post-surgical satisfaction, 60% of the participants who underwent mastopexy were satisfied, and 40% reported positive and high interference in their sexual life.

Of the participants who underwent mastopexy, 70% had already had children. The literature describes the breast as a symbol of femininity and female sexuality9. Thus, it has erogenous power and represents a bodily identity. If the woman suffers significant physical alterations in the breast, including those resulting from breastfeeding, then there will be impairment of the psychological functions. Accordingly, the main motivation of 50% of the participants who opted for mastopexy was the increase of self-esteem.

In our sample, surgeries interfered positively on personal, professional, and/or social life in 44.4% of the participants who underwent mastopexy. This result was expected, as those who undergo mastopexy are usually younger, sexually and professionally active women who have had their breasts modified by changes in skin elasticity owing to pregnancy, breastfeeding, weight fluctuations, and other factors. However, this positive influence was also present in 83.33% of those who did not undergo this specific procedure (p = 0.032).

The positive influence is reflected in several procedures, among them, breast enlargement with silicone prosthesis that revealed that 100% of the participants showed a high post-surgical satisfaction.

On May 17, 2017, the Ibero-Latin American Federation of Plastic Surgery signed a declaration of commitment to implement higher safety in the specialty, and with the purpose of defining actions to reduce the number of deaths and sequels caused by surgery, thus preserving patients’ health. This action is critical to providing a better guarantee of satisfactory aesthetic results and to preserving patients’ lives, in consideration of the world indices in this regard: Brazil and Mexico make up this group, two countries that most perform plastic surgeries in the world15.

All of the participants who participated in this study reported being well-informed about the procedure that they had planned to undergo, the possible therapeutic options according to their needs, and the possible risks and disadvantages of the procedure to be performed. Of the participants in the study, 97.5% reported understanding that aesthetic plastic surgery has no guarantees of specific results, and 55.5% displayed optimism or tranquility facing this situation. These data refer to the participants’ confidence in the surgical team. These findings are relevant and show a greater concern for clarifications to attain higher safety and promote confidence.

CONCLUSION

The study measured the impact of aesthetic mammoplasty on the self-esteem of women. We found an average increase in the self-esteem of the participants who underwent aesthetic mammoplasty, which could indicate that plastic surgery may be considered an appropriate therapy for improving self-esteem.

The types of surgery produced the same outcome regarding the variation of self-esteem. The solely aesthetic-oriented surgeries were as impactful in improving the quality of life and biopsychosocial aspects of the participants as reparative surgeries.

The post-operative satisfaction of a patient depends on the association between a desire for surgically changing one’s body image with consistent and well-structured motivations and a greater concern of surgeons for the legal aspects in relation to providing good guidance on therapeutic options, with clear explanations regarding the potential risks and benefits of the surgical procedure to be performed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the plastic surgeon Tirzah Wynne Cardoso for the encouragement and support, and for entrusting their patients for this study.

COLLABORATIONS

|

GRS |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, conceptualization, data curation, final manuscript approval, investigation, project administration, realization of operations and/or trials, validation, writing - review & editing. |

|

DCA |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, data curation, realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

CV |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

RAC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

GGL |

Visualization, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

LS |

Visualization, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

RAC |

Visualization, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

DP |

Final manuscript approval, project administration, supervision, writing - review & editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Moita GF, Melo CME. O impacto das cirurgias estéticas na qualidade de vida e aspectos psicossociais de pacientes-WHOQOL-Bref aplicado no estudo de caso em uma clínica em Fortaleza-Brasil. Rev Adm Hosp Inov Saúde. 2018;14(4):119-44.

2. Paixão JA, Lopes MF. Alterações corporais como fenômeno estético e identitário entre universitárias. Saúde Debate. 2014;38(101):267-76.

3. Pimentel D. Beleza pura. Estud Psicanal. 2008;31:43-9.

4. Coelho FD, Carvalho PHB, Paes ST, Ferreira MEC. Cirurgia plástica estética e (in) satisfação corporal: uma visão atual. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2017;32(1):135-40.

5. Brito MJA, Nahas FX, Cordás TA, Felix GAA, Sabino Neto M, Ferreira LM. Compreendendo a psicopatologia do transtorno dismórfico corporal de pacientes de cirurgia plástica: resumo da literatura. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(4):599-608.

6. Tambone V, Barone M, Cogliandro A, Stefano ND, Persichetti P. How you become who you are: a new concept of beauty for plastic surgery. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(5):517-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2015.42.5.517

7. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica/Datafolha: Cirurgia Plástica no Brasil. 2009 [acesso 2017 Maio 21]. Disponível em: http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Datafolha_2009.pdf

8. Melo JCDC, Batista MHM, Santos Rosendo AH, Farias SA. Consumo da cirurgia plástica através da vaidade. Cad Cajuína. 2017;2(3):102-12.

9. Guimarães PAMP, Sabino Neto M, Abla LEF, Veiga DF, Lage FC, Ferreira LM. Sexualidade após mamoplastia de aumento. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(4):552-9.

10. Ferreira JB, Lemos LMA, Silva TR. Qualidade de vida, imagem corporal e satisfação nos tratamentos estéticos. Rev Pesq Fisioter. 2016;6(4):402-10.

11. Skopinski F, Resende TL, Schneider RH. Imagem corporal, humor e qualidade de vida. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2015;18(1):95-105. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-9823.2015.14006

12. Masiero LM. Mudanças culturais: uma reflexão sobre a evolução das cirurgias plásticas. Antropol Cuerpo. 2015:62-77.

13. Matera C, Nerini A, Giorgi C, Baroni D, Stefanile C. Beyond Sociocultural Influence: Self-monitoring and Self-awareness as Predictors of Women's Interest in Breast Cosmetic Surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015;39(3):331-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-015-0471-2

14. Foustanos A, Pantazi L, Zavrides H. Representations in plastic surgery: the impact of self-image and self-confidence in the work environment. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31(5):435-42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-006-0070-3

15. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica. Países decidem criar documento mundial sobre segurança em cirurgia plástica. 2017 [acesso 2017 Maio 21]. Disponível em: http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/2017/05/19/paises-decidem-criar-documento-mundial-sobre-seguranca-em-cirurgia-plastica/

1. Universidade Tiradentes, Aracaju, SE,

Brazil

2. Clínica Concept, Aracaju, SE,

Brazil

3. Clínica Integrada Homo, Aracaju, SE,

Brazil

4. Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Aracaju, SE,

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Gabriel Gonçalves Lopes Rua Manoel Andrade, nº 2576 - Coroa do Meio, Aracaju, SE, Brazil Zip Code 49035-530 E-mail: gabriel.pglopes@gmail.com

Article received: October 23, 2018.

Article accepted: February 10, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter